Tumours of the pancreas and hepatobiliary system; the spleen

Carcinoma of the pancreas

This is usually an adenocarcinoma arising from cells lining the ducts. About 80% arise in the head (the largest part) and 20% in the body or tail. Cancers often form a well-differentiated ductular pattern but despite this, it is a highly malignant tumour. It metastasises early to lymph nodes, to peritoneum, and to liver via the portal vein (see Fig. 24.1). At presentation, less than 20% are resectable and the overall prognosis is dire.

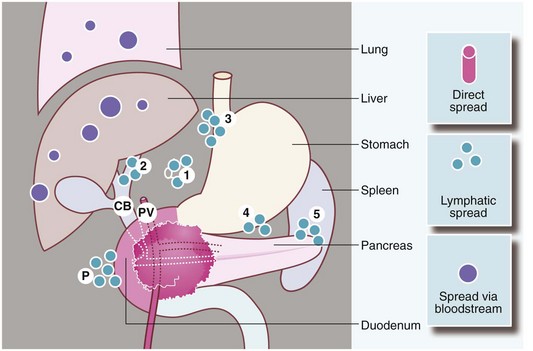

Fig. 24.1 Spread of carcinoma of the pancreas

Direct spread may involve the common bile duct CB where it traverses the pancreas, the duodenum and the portal vein PV. Lymphatic spread may reach the paraduodenal peritoneum P and the nodes of the coeliac axis 1, the porta hepatis 2, the lesser and greater curves of the stomach 3, 4 and the hilum of the spleen 5. Spread may also occur via the bloodstream to the liver, lungs, etc.

Clinical features of ductal pancreatic carcinoma

There are no useful screening tests and so pancreatic cancer nearly always presents with symptoms and signs. The main features are substantial weight loss (80%), abdominal pain (60%) and obstructive jaundice (50%). Ascites and an abdominal mass are uncommon (Box 24.1).

Obstructive jaundice

Jaundice, often without pain early on, develops over several weeks, and is associated with pale stools and dark urine. These clinical features are dramatic and never ignored. The jaundice is caused by common bile duct compression in its course through the pancreatic head. As a result, the proximal bile duct dilates and the gall bladder may become palpable (Courvoisier’s law, see Ch. 18, p. 259). Bile duct obstruction may also be caused by metastases in porta hepatis lymph nodes. Liver metastases alone rarely cause jaundice.

Approach to investigation of suspected pancreatic carcinoma (Box 24.2)

A patient with obstructive jaundice should be investigated as described in Chapter 18, p. 258. If pancreatic cancer is likely, optimum management is via a streamlined diagnostic pathway carried out in a specialised, high-volume pancreatic centre.

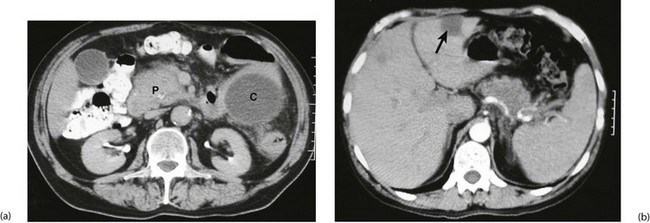

Lesions in the body and tail of the pancreas

When pancreatic cancer is suspected in a non-jaundiced patient, abdominal CT can confirm the diagnosis more reliably than ultrasound, although small tumours may be missed (see Fig. 24.2a and b). CT scanning also indicates retroperitoneal and portal vein invasion; it shows metastases in liver and lymph nodes and CT-guided needle biopsy can obtain histopathology specimens, all of which can determine resectability. CT scanning can understage the disease, chiefly because it does not detect small-volume hepatic and peritoneal deposits.

Management of pancreatic carcinoma

Surgical resection and adjuvant therapy

It is an unfortunate truth that most patients with pancreatic cancer present at an incurable stage. Only about 15–20% have apparently localised disease with a potential for surgical cure. Whipple’s operation (pancreatico-duodenectomy, see Fig. 24.6, p. 330) is the standard type of operation where resection of the pancreatic head is indicated. It is a major undertaking with high operative morbidity and mortality; even in specialist centres, mortality is 1–2% with a 15–20% morbidity (pancreatic leaks, delayed gastric emptying, wound infections) and a 5-year survival of only 15–20%.

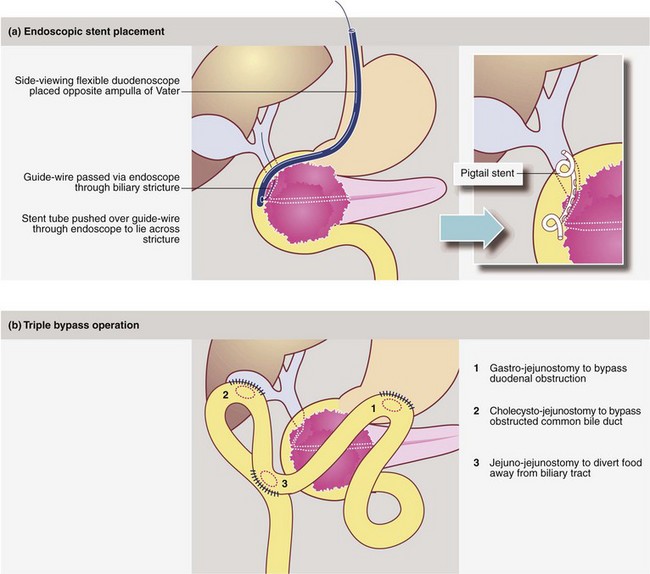

Palliation of pancreatic cancer

When there is obvious widespread disease, the patient should be allowed to die with minimal surgical interference but with careful attention to symptom control. Good analgesia is fundamental; severe pain can often be relieved by permanent coeliac ganglion blockade, performed percutaneously. Obstructive jaundice can usually be relieved by inserting a biliary stent at ERCP. If unsuccessful, a percutaneous transhepatic cholangiogram (PTC) can help pass a guide-wire to the duodenum to facilitate ERCP or else place a stent from above; techniques are illustrated in Figure 24.3. Surgical bypass (usually a ‘triple bypass’, see Fig. 24.3) may provide longer-lasting relief from jaundice and duodenal obstruction than stenting. Duodenal obstruction alone can be bypassed by endoscopic stent placement or laparoscopic gastroenterostomy.

Endocrine tumours of the pancreas

Insulinomas (Fig. 24.4)

The most common endocrine tumours are insulinomas derived from beta cells, but they occur in only 1.7 per million people per year. The main symptoms are cerebral disturbances caused by hypoglycaemic attacks, often when fasting or exercising and relieved by oral or intravenous glucose. About 90% of insulinomas are single and 90% are benign and amenable to curative resection. They occur with equal frequency in the head, body and tail of the pancreas. Malignancy is only diagnosed if metastases appear.

Multiple endocrine neoplasia syndromes (MEN)

• MEN 1—islet cell tumours, pituitary adenomas and parathyroid hyperplasia

• MEN 2a—medullary thyroid carcinoma (often in childhood), phaeochromocytoma and parathyroid adenoma or hyperplasia

• MEN 2b—medullary thyroid carcinoma, phaeochromocytoma, mucosal and gastrointestinal neurofibromas and Marfanoid habitus

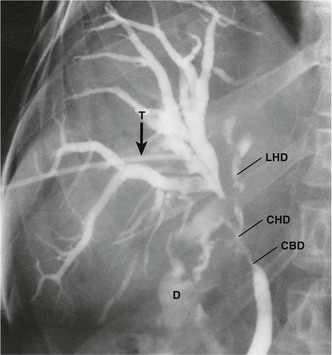

Biliary and periampullary tumours

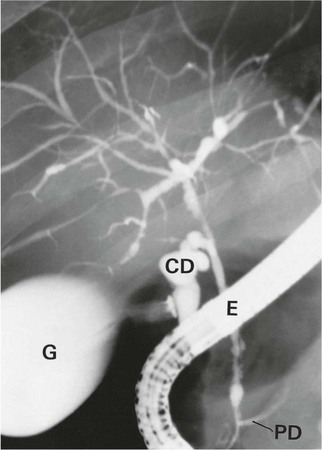

Cholangiocarcinomas have a dense fibrous stroma and grow along ducts rather than producing focal proliferative lesions. The resulting smooth elongated stricture can be demonstrated by ERCP, MRCP or transhepatic cholangiography (see Fig. 24.5). Histological proof of malignancy may be elusive owing to the fibrous nature of the tumour. Unlike pancreatic cancer, cholangiocarcinomas are often slow-growing and metastasise late. Despite this, lymph node involvement at presentation is common, and extension along bile ducts and involvement of portal vein and hepatic arterial branches results in a low operability rate and an even lower long-term survival. Radical procedures combining partial hepatectomy with excision of the involved biliary tree and ‘en bloc’ portal vein resection and reconstruction may offer better clearance and improved survival for selected patients.

Management of extrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and periampullary carcinoma

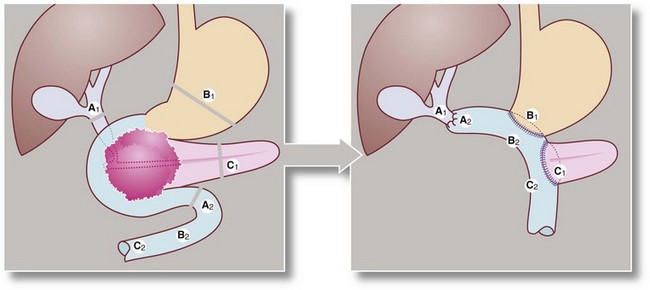

Extrahepatic and periampullary cancers can often be successfully treated by Whipple’s pancreatico-duodenectomy, Figure 24.6. Operative morbidity and mortality are similar to the operation for pancreatic cancer, but the prognosis is often better because the obstructing tumour is usually small, with less extensive spread.

Fig. 24.6 Whipple’s operation (pancreatico-duodenectomy)

(a) Structures are divided at the lines A1, A2, B1, C1. (b) The distal half of the stomach, the entire duodenal loop, the head and body of the pancreas and the lower end of the common bile duct are all removed, then reconstruction is performed with anastomoses between A1 and A2, B1 and B2 and C1 and C2

Primary sclerosing cholangitis

Primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) is a rare condition, probably of autoimmune origin, causing progressive fibrosis and multiple biliary strictures. Luminal narrowing causes gradual and progressive obstructive jaundice and, later, secondary cirrhosis. It may arise sporadically but often occurs in longstanding ulcerative colitis. Bile duct stenosis is usually diffuse, with a characteristic ERCP appearance (see Fig. 24.7), but just occasionally it is localised to the extrahepatic biliary system. Here the radiological appearance is indistinguishable from cholangiocarcinoma, causing a diagnostic predicament. Management is by endoscopic dilatation of clinically significant strictures and prescribing choleretic drugs to improve bile flow. In advanced cases, liver transplantation is an option; interestingly, up to a third demonstrate cholangiocarcinoma in the excised liver.

Liver tumours and abscesses

The spleen

The spleen plays a major role in defence against infections, particularly involving encapsulated organisms. It also filters and removes senescent or defective blood cells. Primary splenic diseases are uncommon but a range of haematological disorders may involve the organ and usually manifest as splenomegaly (see Ch. 18, p. 263). Historically, splenectomy was common in myeloproliferative disorders and often used for diagnosis, but is now rarely indicated except to treat hypersplenism, i.e. excessive consumption of cellular blood components or for symptom control in pain associated with massive splenomegaly. The surgeon is most frequently involved in repair, partial resection or removal of a normal spleen after trauma or iatrogenic injury (Ch. 15, p. 207).

Elective splenectomy

Laparoscopic splenectomy has become the standard technique for most elective cases and is outlined in Ch. 10, p. 145. The most common elective indication for splenectomy is immune thrombocytopenic purpura (ITP) in which anti-platelet antibodies lead to platelet destruction and an increased risk of spontaneous haemorrhage. Splenectomy is curative in about 85% of cases.