Tumours of the kidney and urinary tract

Introduction

Two types of cancer arise from the renal parenchyma: renal cell carcinomas and nephroblastomas. Renal cell carcinomas (also known as renal adenocarcinomas and previously as hypernephromas) are confined to adults. Nephroblastomas (Wilms’ tumours) are developmental in origin and present in infancy or early childhood (Ch. 51). Occasional benign renal tumours also occur, e.g. oncocytoma, adenoma and angiomyolipoma (see Box 36.1).

Renal cell carcinoma

Pathology of renal cell carcinoma

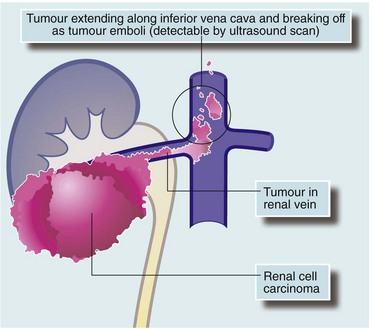

Renal cell carcinomas vary in grade of malignancy. Small isolated tumours are often found incidentally at autopsy. Many pathologists regard tumours of less than 2 cm as virtually benign as they rarely display invasion or metastasis. Bilateral tumours are present in about 5%. Large tumours invade surrounding tissues and may metastasise to para-aortic lymph nodes. Advanced renal cell carcinoma characteristically extends into the lumen of the renal vein and into the inferior vena cava (‘tumour thrombus’—see Fig. 36.1). Distant spread is typically to lung, liver and bone. Lung metastases are often typical discrete ‘cannonball secondaries’. Isolated metastases occasionally develop in the brain, bone and elsewhere.

Clinical features of renal cell carcinoma

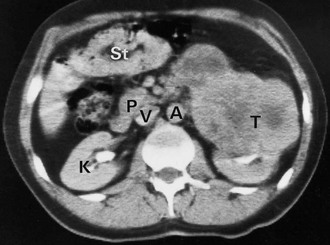

The classic presentation is with the triad of haematuria, a mass and flank pain; although all three features only occur in about 15% of cases (see Fig 36.2), one is present in 40% of patients. Commonly, diagnosis is made incidentally by discovering a tumour on ultrasonography or CT scanning. Renal cell carcinomas often become large before diagnosis owing to their retroperitoneal position; unfortunately, tumours larger than 8 cm have an 80% chance of having already metastasised. Common and uncommon presenting features of renal cell carcinoma are summarised in Box 36.2.

Approach to investigation of suspected renal cell carcinoma

Ultrasound investigation reliably distinguishes simple benign cysts from solid masses most likely to be tumours, and can demonstrate tumour thrombus in the inferior vena cava. CT scanning is used to stage the disease by assessing invasion of perinephric tissues and by demonstrating regional lymph node or liver metastases (see Fig. 36.3).

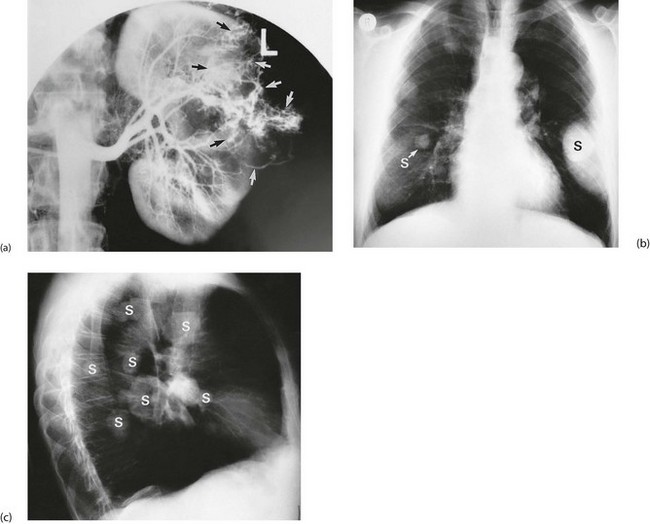

Arteriography is still occasionally employed in the case of solitary unilateral or bilateral tumours to assess the prospects for segmental resection. Renal tumours have a characteristic circulatory pattern distinct from normal kidney (see Fig. 36.4a). Arteriography is also employed if therapeutic embolisation is being considered to reduce the vascularity of a tumour before surgery.

A full blood count is performed to look for anaemia or polycythaemia and a chest X-ray taken to look for pulmonary metastases (see Fig. 36.4b, c). No other preoperative investigations are usually required.

Urothelial carcinoma (transitional cell carcinoma)

Clinical features of urothelial carcinoma

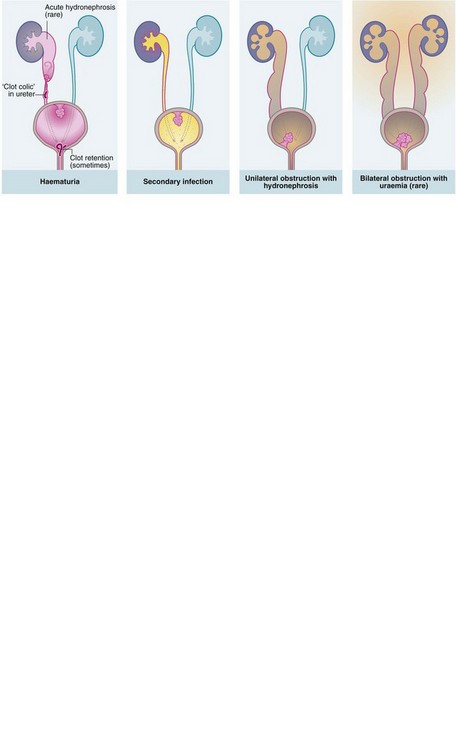

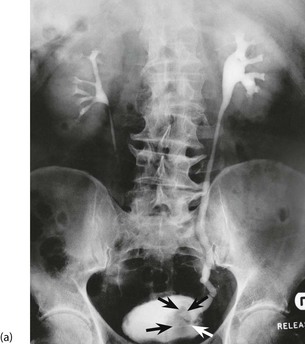

urothelial carcinoma usually presents with painless haematuria (see Fig. 36.5). Very occasionally, an upper tract lesion may cause ureteric colic (clot colic) and long stringy clots are seen in the urine. If bleeding is gross, clots may cause ureteric obstruction. Rapid bleeding from a bladder tumour may cause clot retention, i.e. acute retention of urine due to clot obstruction. Bladder tumours arising near a ureteric orifice can obstruct one ureter, causing hydronephrosis. Rarely, bilateral obstruction causes uraemia. Bladder tumours also predispose to infection; unexplained recurrent urinary tract infections need investigating to exclude UC as a cause. Tumour invasion near the bladder neck may cause incontinence but this is usually preceded by haematuria or infection.

Investigation of suspected urothelial carcinoma

Confirmed haematuria in the absence of infection must be investigated. Ultrasound examination may reveal hydronephrosis if there is ureteric involvement by UC. Contrast CT scanning will outline the upper tract as well as the renal parenchyma. IVU can also outline the upper tract, but is becoming obsolete (see Fig. 36.6). Imaging is followed by cystoscopy, the only reliable method of examining the lining of the bladder and urethra. If there is an upper tract tumour, cystoscopy may reveal blood emerging from a ureteric orifice.

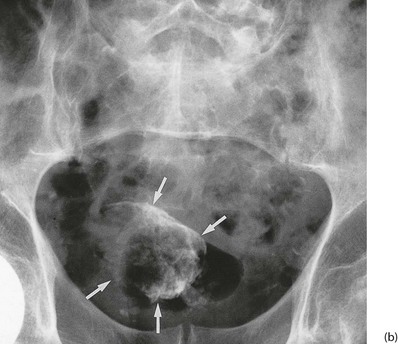

Staging of urothelial tumours of the bladder

The TNM clinical system widely used in staging bladder tumours is illustrated in Figure 36.7 (the ‘T’ is the clinical stage of the tumour). In addition, some pathologists grade bladder tumours according to P and G pathological criteria. The ‘P’ system (small p for the biopsy specimen and capital P for the whole specimen) classifies the extent of invasion on gross anatomical and histological grounds. The ‘G’ system grades the lesion by degree of histological differentiation (G1 = well differentiated, G2 = moderately differentiated and G3 = poorly differentiated or undifferentiated). Thus, as an example, a pathologist may report a biopsy as pT2, G3.

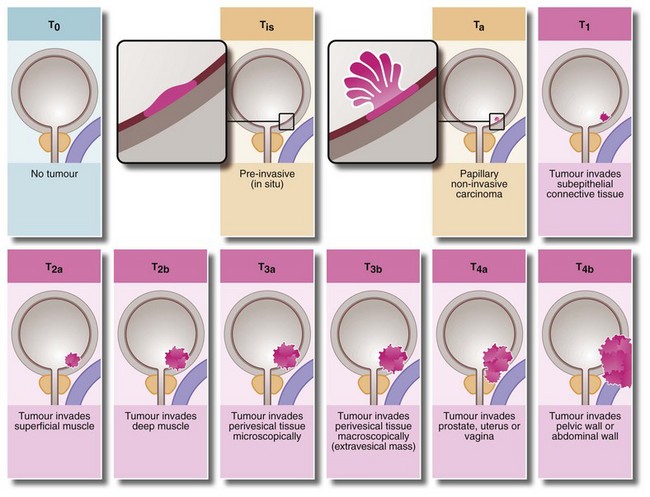

Management of urothelial carcinoma

As shown in Figure 36.8, bladder tumours classified as Ta or T1 can usually be completely resected. Single-dose intravesical chemotherapy with mitomycin C has been shown to reduce the recurrence rate after the initial TURBT in Ta or T1 disease. T1 lesions are notoriously recurrent and if they recur repeatedly, weekly courses of intravesical chemotherapy or BCG is the treatment of choice. For T2/T3 lesions, the preferred treatment in a fit patient is radical cystectomy. The tumour can sometimes be downstaged before surgery by neoadjuvant systemic chemotherapy. Radiotherapy is a good alternative for the unfit or older patient, in those unwilling to undergo cystectomy, or for relapse after initial cystectomy or initial systemic chemotherapy. There is no proven role for radiotherapy in superficial lesions.

Unusual urinary tract tumours

The uncommon squamous cell carcinoma of the urinary tract is diagnosed and treated along similar lines to urothelial carcinoma. Many develop as a complication of schistosomiasis. Distal urethral lesions are managed in the same way as penile carcinoma (see Ch. 33). Adenocarcinoma is rare but can occur anywhere in the bladder, most often in a urachal remnant at the vault. Tumours of this type can often be removed by segmental resection of the bladder.