CHAPTER 102 TUMORS OF THE PERIPHERAL NERVES

The peripheral nervous system is affected by neoplastic disease in the following ways:

Tumors of the peripheral nerves (PNTs) are sufficiently common that they are encountered by surgeons or neurologists at regular intervals but infrequently enough to still cause perplexity in diagnosis and treatment. Too many cases of benign schwannoma are subjected to biopsy, which damages the parent nerve, inflicts pain, and increases the difficulties surrounding excision; too often the true nature of the swelling and of its anatomical relations is not appreciated, so that the nerve trunk is excised. Even worse, inadequate biopsy or incorrect interpretation of that biopsy in a malignant tumor of nerve leads to inadequate treatment.1

The classification used in this chapter is displayed in Table 102-1. The true nature of PNT has been greatly clarified by electron microscopy, immunohistochemistry, and genetic studies. Perineurial cells arise from fibroblasts.2 Transmission electron microscopic studies have shown that schwannomas do indeed arise from Schwann cells; ultrastructural characteristics enable the distinction among schwannoma, neurofibroma, and perineurioma.3 Folpe and Gowan4 emphasized the role of immunocytochemistry in the analysis of PNT, whereby specific antigens on cells of neural origin can be demonstrated by polyclonal or monoclonal antibodies. The strong expression of S-100 by Schwann cells is particularly important in distinguishing between the large schwannomas of the retroperitoneum and soft tissue sarcomas. The perineurial cell does not express S-100 but does express the epithelial membrane antigen. Fibroblasts express vimentin and fibromentin. Immunoreactivity, cytogenetic, and molecular genetic analyses demonstrate that Ewing’s sarcoma, Askin’s tumor of the chest wall, the primitive neuroectodermal tumor of bone, and neuroepithelioma are variations from a common neural origin, distinct from neuroblastoma. The cells of Ewing’s sarcoma exhibit characteristic reciprocal translocation of the long arms of chromosomes 11 and 21, in common with other tumors of this group.5–8

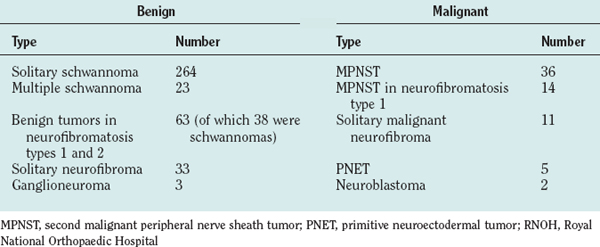

TABLE 102-1 Classification of Peripheral Nerve Tumors

| Type | Benign | Malignant |

|---|---|---|

| Nerve sheath tumors | ||

| Neural tumors | Ganglioneuroma |

The clinical diagnosis of most PNTs, whether benign or malignant, is usually fairly straightforward in cases in which the swelling is located within the limbs. Supplementary investigations are necessary to confirm that diagnosis and to clarify the location of the tumor, its size, and its relation to vital structures. The possibility of a second malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor (MPNST) or of premalignant change within a benign lesion is a particular problem in NF1. A swelling of a nerve may masquerade as PNT and yet may, in fact, be an expression of generalized neuropathy (Figs. 102-1 and 102-2).

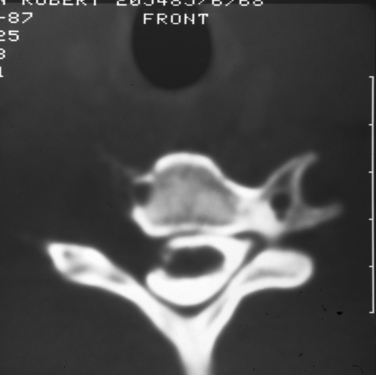

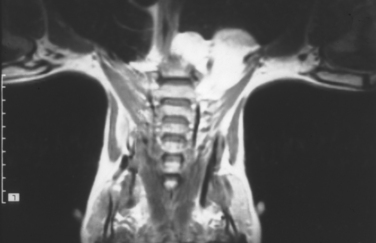

Plain radiographs of the affected anatomy should always be obtained before any computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging. For most PNTs, magnetic resonance imaging is particularly valuable in showing the relations of the tumor and in indicating the extent of spread into the skeleton or spinal canal.9 Magnetic resonance angiography is probably superior to digital subtraction angiography in demonstrating the relation of the tumor to adjacent great vessels. Computed tomography with contrast enhancement is required in the analysis of tumors extending within the spinal canal (Fig. 102-3).

BIOPSY

Biopsy should not be performed when the clinical diagnosis of benign PNT is secure. There are some objections to biopsy in MPNST: The intervention must breach tissue planes; an inadequate sample or incorrect analysis may lead to a false diagnosis of benign lesion in MPNST or of malignancy within a benign lesion. A biopsy specimen in MPNST should be adequate for defining the cell of origin, and this is particularly relevant in primitive neuroectodermal tumors, for which adjuvant therapy is an essential element in treatment. The staging of sarcomas of bone or of other soft tissues is a well-established and accepted practice. However, the compartment for an MPNST is the trunk nerve itself, and the authors have found centripetal extension of up to 20 cm within an apparently normal nerve trunk in some cases. Conventional staging investigations do not detect early malignancies at other sites in NF1, nor are they particularly good in detecting the early stages of transformation from benign to malignant lesions. MPNSTs are best treated in units that have access to all essential modalities of diagnosis. The operating surgeon should be responsible for the planning of biopsy and also for examination of all and of any material with colleagues in a multidisciplinary team (Fig. 102-4).

The authors’ unit has treated more than 450 patients with PNTs (Table 102-2). Their experience and those of others in the management of these tumors are summarized as follows.

THE BENIGN SCHWANNOMA

This is the most common of all true PNTs, and it can be removed without impairment for function of the nerve of origin. Eighty percent of affected patients were between 30 and 69 years of age; 55% were male. The upper limb was the site of the tumor in more than 70% of cases; the brachial plexus and adjacent spinal nerves, in a little more than one third. Schwannomas can be found in bone, muscle, or viscera. Massive mediastinal or retroperitoneal tumors are not rare. The authors have found multiple schwannomas in 23 patients, and the tumor is common in NF1. Loss of function occurs when the tumor arises in an enclosed space. Most intraspinal/extraspinal tumors (dumbbell tumors) are schwannomas, and affected patients may present with quite advanced afflictions of the spinal cord. Bilateral vestibular tumors are pathognomonic of neurofibromatosis type 2 (NF2). Schwannomas arise from Schwann cells, which invest cranial nerves III to XII close to their origin. Malignant transformation of a benign schwannoma is rare.10

Pathology

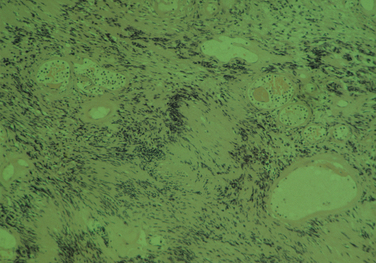

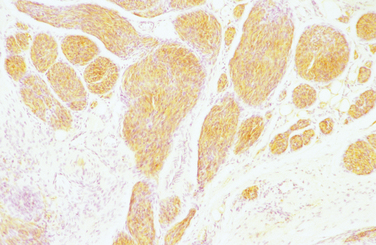

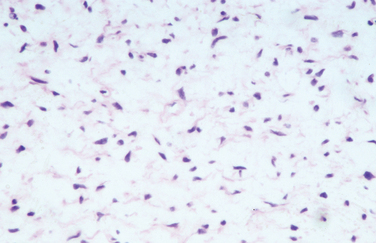

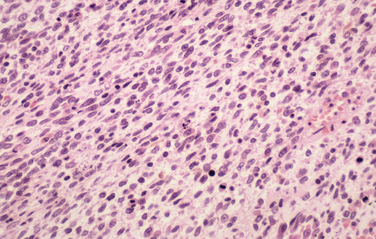

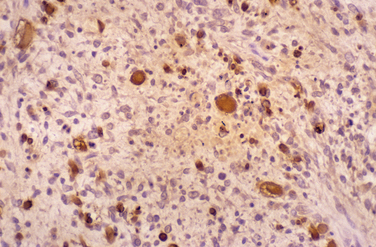

The diagnostic feature is the organization of Schwann cells into areas of compact bundles (Antoni-A tissue) or a less orderly arrangement of spindle or oval cells in a loose matrix (Antoni-B tissue). There may be an abrupt change from one to the other. Palisades of compact parallel rows of cells forming Verocay bodies are a feature of Antoni-A tissue. In larger tumors, the nuclei may appear hyperchromatic, large, and multilobed (ancient schwannomas) and a misdiagnosis of malignancy may be made on the basis of these findings, as it may also be for schwannomas formed exclusively from Antoni-A tissue (the cellular variety). This error is prevented by consideration of the nature of the tumor as a whole and by immunohistochemistry. Strong expression of S-100 distinguishes the schwannoma from soft tissue sarcomas such as leiomyosarcoma (Figs. 102-5 and 102-6).11

Clinical Features

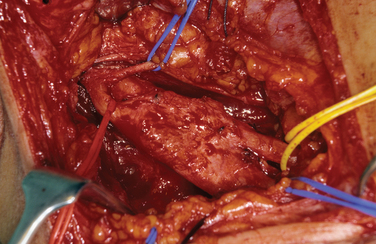

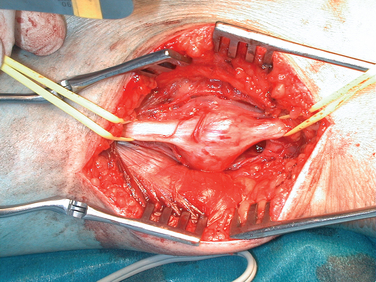

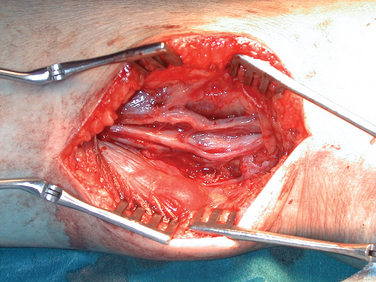

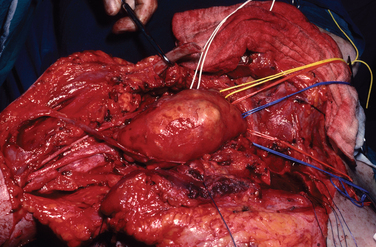

For tumors arising within the trunk nerves of the limbs, the exposure should be linear along the course of the nerve and long enough to enable display of the nerve trunk above and below the tumor of adjacent arteries, veins, and other tissues. Magnification with loupes or operating microscopes is helpful. With the tumor exposed and the nerve adequately mobilized, an incision is made in the epineurium, remote from intact bundles, which are seen coursing over the tumor and displayed around it. The plane of dissection lies between the true glistening capsule of the tumor and the bundles of the nerves lying within their epineurium. A nerve stimulator is an essential instrument during the operation, and it is particularly valuable in defining conducting elements within bundles that are so tightly splayed over the capsule of the tumor that they appear almost translucent. It is usual to find one slender bundle entering the proximal pole of the tumor and exiting at the distal pole, which is removed with the tumor. Conduction across this bundle is rare. A number of severe complications have been seen in patients referred to the authors after primary intervention. Among these are 24 cases of complete excision of a major nerve or nerves and another 18 in which there was partial excision of the nerve or nerves. Severe neuropathic pain complicated needle biopsy in 11 more patients (Figs. 102-7 and 102-8).

The brachial plexus and the superior mediastinum are common sites for large schwannomas. The transclavicular exposure was designed to provide adequate exposure and control of the venous trifurcation, the first part of the subclavian artery, the vertebral artery, and the recurrent laryngeal nerve, and it has been safely applied in more than 50 cases.12 The posterior subscapular route is valuable for tumors that lie in the posterior mediastinum (Fig. 102-9).13

THE SOLITARY NEUROFIBROMA

A typical neurofibroma arising in a major nerve trunk is easily recognizable. These tumors are significant for three reasons: They may grow to a very large size; they may extend along a spinal nerve into the spinal canal; and there is a slight but definite risk of malignant transformation.11 The neurofibroma of a trunk nerve is not easily separable from nerve bundles; therefore, enucleation is not always possible. Most of the large peripheral neurofibromas arise from slender trunks, and so their removal is relatively straightforward and causes little loss of function (Figs. 102-10 and 102-11).

OTHER BENIGN TUMOR-LIKE CONDITIONS

Two of these merit attention because they present difficulties in diagnosis.

Lipofibromatous Hamartoma

This benign lesion most commonly involves the median nerve and usually manifests as a fluctuant, tender swelling extending from above the wrist into the palm of the hand. At surgery, the nerve is found entering a large, yellowish, fatty tumor. Individual nerve bundles are so closely involved that removal of the tumor is impossible without resection of the nerve. Biopsy carries risks of pain and loss of function. There is overgrowth of epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium. Transmission electron microscopic studies reveal perineurial hyperplasia and excessive collagen.11

The Intraneural Ganglion

This tumor most commonly involves the common peroneal nerve at the knee. It is one of the few benign disorders of nerves that cause loss of function. Spinner and colleagues (2003)14 demonstrated that the cyst extends along the articular branch from the proximal tibiofibular joint into the deep division of the common peroneal nerve. Successful operation requires excision of the articular branch, in addition to decompression of the main nerve.

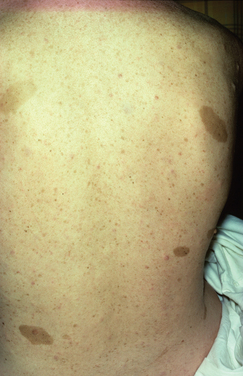

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS

NF1 is much more common than NF2, with an incidence of about 1 per 3000 persons in comparison with 0.1 per 100,000 (Table 102-3). Only one half of the authors’ patients were aware of their condition, and the complications of the disease for themselves and their families were known to only a few. The surgeon may be the first to make the diagnosis and should work closely with a clinical geneticist so that the patient and family are adequately advised and supported. Support groups such as LINK in the United Kingdom, have produced excellent fact sheets on NF1 and NF2, and patients have been much helped by contact with such groups. NF1 is a disorder of the central and peripheral nervous systems, the skeleton, and the blood vessels. It is progressive, and there are four major causes of premature death: massive plexiform neurofibroma in the mediastinum, involving the airways; astrocytoma of the optic chiasm, brain, or cerebellum; cervicoparaspinal neurofibroma; and MPNST. The risk of MPNST in a patient with NF1 is about 3%. These tumors are rare in the first decade, manifest during adolescence or early adulthood, and their prognosis is poor (Fig. 102-12).6,15

TABLE 102-3 Diagnostic Features of Neurofibromatosis Types 1 and 2

| Feature | Type 1 (Peripheral Neurofibromatosis) | Type 2 (Central Neurofibromatosis) |

|---|---|---|

| Incidence | 1 to 3 per 4000 | 0.1 per 100,000 |

| Inheritance | Autosomal dominant | Autosomal dominant |

| Gene locus | Proximal long arm of chromosome 17 | Distal long arm of chromosome 22 |

| New mutations account for one third to one half of new cases | New mutations account for up to two thirds of new cases | |

| Diagnostic criteria | ||

| 1 | Six or more café-au-lait macules over 5mm in greatest diameter in prepubertal individuals and over 15mm in greatest diameter in postpubertal individuals | Bilateral cranial nerve VIII masses seen with appropriate imaging techniques (e.g., CT or MRI) |

| 2 | One plexiform neurofibroma | |

CT, computed tomography; MRI, magnetic resonance imaging.

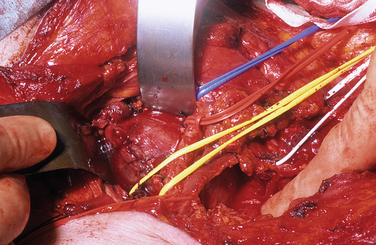

Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumors

The most dangerous of these arise in patients with NF1 and account for about one third of all these tumors. The patients are younger, the incidence peaking between the ages of 20 and 30 years, and there is a tendency for tumors to arise more centrally. The prognosis is worse than it is for the solitary malignancy. MPNST develops in about 3% to 5% of patients with NF1. The rate of survival 5 years after the diagnosis ranges from 16% to 30% in published series (Figs. 102-13 and 102-14).16

The second group includes tumors caused by irradiation and accounts for about 10% of all MPNSTs.6 It is important to distinguish these tumors from recurrence of primary malignancy, because some of them can be treated successfully by resection.

The prognosis for solitary MPNST is similar to that for soft tissue sarcomas in general, with a 5-year survival rate of about 50%. The incidence peaks in the fourth, fifth, and sixth decades of life, and the tumor tends to arise more peripherally.16

The most important factors in the prognosis for all of these tumors are their size and manifestation. Tumors in NF1 tend to arise more centrally in deep-seated locations, and the rate of growth is faster.

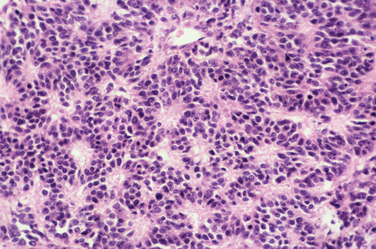

The most common histological appearance is reminiscent of fibrosarcoma with masses of spindle-shaped cells organized into wavy lamellae. Irregularity of the cells and a wavy or buckled appearance of the nuclei are often found. Metaplastic differentiation occurs in about 20% of patients. Bone, cartilage, and muscle are the most commonly affected tissues; epithelioid differentiation into glandular or squamous tissue is less common. The prognosis for the “triton” tumor, which shows differentiation into skeletal muscle, is particularly poor. Transmission electron microscopic studies suggest that about 25% of these tumors show features of Schwann cells; fibroblasts predominate in about another 25%. Many MPNSTs do not stain for the S-100 protein, and examination for multiple neural markers is advised (Figs. 102-15 to 102-17).16

Management

Amputation is necessary when the epineurium has been breached or with recurrence. Lusk and colleagues17 advised forequarter amputation in patients with MPNSTs arising within the brachial plexus. This is necessary for recurrence after an apparently adequate excision or when there is such involvement of the plexus that no function can be preserved. It may be necessary for palliation even if it cannot be cured. Of 15 patients with tumors in known NF1 in the authors’ experience, 13 died within 2 years of diagnosis, and only one patient remained apparently disease free at 3 years. Of the 35 patients with solitary tumors, six died within 2 years of diagnosis, and seven more are known to have disease. Of the 22 apparently disease free at a minimum of 5 years after surgery, 14 were treated by excision of the nerve, 5 by amputation of the limb, and 3 by forequarter amputation.

Birch R, Bonney G. The peripheral nervous system and neoplastic disease. In: Birch R, Bonney G, Wynn Parry CB, editors. Surgical Disorders of the Peripheral Nerves. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1998:335-372.

Fletcher JA. Cytogenic analysis of soft tissue tumors. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:125-146.

Meltzer PS. Molecular genetics of soft tissue tumors. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:103-124.

Spinner RJ, Atkinson JLD, Teil RL, et al. Peroneal intraneural ganglia: the importance of the articular branch. A unifying theory. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:330-343.

1 Birch R, Bonney G. The peripheral nervous system and neoplastic disease. In: Birch R, Bonney G, Wynn Parry CB, editors. Surgical Disorders of the Peripheral Nerves. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1998:335-372.

2 Bunge MB, Wood PM, Tynan LB, et al. Perineurium originates from fibroblasts: demonstration in vitro wIth a retroviral marker. Science. 1989;243:229-231.

3 Henderson WH, Papadimitriou JM, Coleman M. Ultrastructural Appearances of Tumours: Diagnosis and Classification of Human Neoplasia by Electron Microscopy, 2nd ed. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 1986. Section Three: Neural Tumours.

4 Folpe AL, Gowan AM. Immunohistochemistry for analysis of soft tissue tumors. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:119-246.

5 Fletcher JA. Cytogenic analysis of soft tissue tumours. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:125-146.

6 Giannini C. Tumors and tumor-like conditions of peripheral nerves. In: Dyck PJ, Thomas PK, editors. Peripheral Neuropathy. 4th ed. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2005:2585-2606.

7 Meltzer PS. Molecular genetics of soft tissue tumors. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:103-124.

8 Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Primitive neuroectodermal tumors and related lesions. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:1265-1322.

9 Kuntz C, Blake L, Britz G, et al. Magnetic resonance neurography of peripheral nerve lesions in the lower extremity. Neurosurgery. 1996;39:750-757.

10 Woodruff JM, Selig AM, Crowlely K, et al. Schwannoma with malignant transformation: a rare distinctive peripheral nerve tumor. Am J Surg Pathol. 1994;18:882.

11 Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Benign tumors of the peripheral nerves. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:1111-1208. Chapter

12 Birch R, Bonney G, Marshall RW. A surgical approach to the cervico-dorsal spine. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72:904-907.

13 Kline DG, Kott J, Barnes G, et al. Exploration of selected brachial plexus lesions by the posterior subscapular approach. J Neurosurg. 1978;49:872-879.

14 Spinner RJ, Atkinson JLD, Teil RL, et al. Peroneal intraneural ganglia: the importance of the articular branch. A unifying theory. J Neurosurg. 2003;99:330-343.

15 Riccardi VM. Neurofibromatosis. In: Kennard C, editor. Recent Advances in Clinical Neurology, No. 6. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1990:186-208.

16 Weiss SW, Goldblum JR. Malignant tumors of peripheral nerves. In: Weiss SW, Goldblum JR, editors. Enzinger and Weiss’ Soft Tissue Tumors. 4th ed. St. Louis: Mosby; 2001:1209-1264.

17 Lusk MD, Kline DG, Garcia CA. Tumour of the brachial plexus. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:439-453.