CHAPTER 37 RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME

Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is the most common neurological sleep disorder. It was first described in 1672 and was rediscovered in 1945 by K. A. Ekbom,1 who extensively studied this disorder and contributed important findings that are still relevant today. Major advances in the clinical definition of RLS, in understanding the basic mechanisms, the discovery of genetic factors, and the successful treatments of RLS have increased medical attention in the field of neurology. However, awareness of the disorder among general physicians is still low, despite its high prevalence and significant morbidity. RLS is often misdiagnosed, underdiagnosed, or undiagnosed. One survey showed that the rate of correct diagnosis of RLS by general physicians is less than 7% of that of correct diagnosis by specialists. Even when diagnosed, RLS is often not appropriately treated.2 However, the prevalence of individuals whose symptoms of RLS are sufficiently severe for them to seek medical advice is estimated at approximately 3% of general practice populations.2 Increased awareness will improve the rate of recognition and treatment of RLS, which most often dramatically improves patients’ lives.

CLINICAL FEATURES AND DEFINITION OF RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME

RLS is a distressing neurological sensorimotor disorder characterized by an almost irresistible urge to move the limbs that is most often but not necessarily accompanied by uncomfortable sensations in the legs. RLS symptoms are evoked by rest, such as lying down or sitting, and are worse in the evening or night. Patients describe the sensations, most commonly deep in the legs, as “creepy-crawly,” “like an electric current,” “pulling,” “tearing,” “itching bones,” “aching,” or “throbbing.” Because the symptoms are unfamiliar, patients often find them extremely difficult to describe. The regions between the knees and the ankles are especially affected, whereas the feet are frequently spared. In response to the discomfort, patients often rub or stretch and flex their legs, turn in bed, or pace the floor, because passive or active movement characteristically provides temporary relief. The arms may also be involved, particularly in patients with severe RLS. Because the symptoms of RLS occur predominantly in the evening or during the night, RLS has a significant effect on sleep, and patients often present with a sleep problem. In addition to difficulty initiating sleep, many patients with RLS have problems maintaining sleep, with frequent awakenings or short arousals that result in poor sleep efficiency. Patients with moderate to severe RLS may sleep on average less than 5 hours per night and may chronically have less sleep time than do patients with almost any other persistent disorder of sleep.3 In many patients with RLS, quality of life is poor, and these patients are at increased risk for depressive and anxiety disorders.4,5 Approximately 80% to 90% of the patients with RLS have associated nocturnal, involuntary periodic limb movements (PLMs)—during sleep (PLMSs) or during wakefulness (PLMWs)—which are usually present in the legs.6 PLMs are mostly rhythmic extensions of the big toe and dorsiflexion of the ankle that resemble the Babinski reflex, with occasional flexion of the knee and hip.7 Movements are often bilateral, involving both legs, but may be predominant in one leg or alternate between legs. The quantification of PLMs is routinely performed in the sleep laboratory by recording both anterior tibialis muscles with surface electrodes. Polysomnographic recordings show that they tend to occur every 20 to 40 seconds and are frequently associated with arousals or complete awakenings. Thus, PLMs further contribute to sleep fragmentation, especially in advanced cases in which the PLMS arousal index (number of PLMS-associated arousals per hour total sleep time) may be very high. PLMs may be assumed if bed partners of patients with RLS report nocturnal kicking of the leg or sometimes if patients themselves experience involuntary jerks of the legs while lying in bed.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Well-performed epidemiological studies have concordantly shown that the prevalence of RLS in the general population is between 5% and 10%8–13 and that RLS prevalence is higher in women with more births.2,9,12–15 In addition, one study showed that the frequency of RLS in women increases by the number of births.13 The time of onset varies between early childhood and 80 years of age or even older. In retrospective surveys, 23%16 and 13%6 of adult patients with RLS reported the onset of RLS before the age of 10 and 25% between 10 and 20 years.6,16 Although valid data about the prevalence of RLS in adults exist, respective data for the adolescent population or children are lacking. However, existing data suggest that RLS and sleep disturbances caused by RLS are a frequent but undiagnosed problem in this younger age group. RLS varies in severity, and the prevalence of adults in a general practice population whose RLS is severe enough to seek medical advice has been shown to be about 3.4%.2 Despite the prevalence, there is a lack of awareness of RLS among health care providers. One epidemiological study showed that only 12.9% of cases were accurately diagnosed by the general practitioner, although patients explicitly reported their symptoms. The rate of correct diagnosis of RLS by general practitioners is less than 7% that by specialists. Even when diagnosed, RLS is often not appropriately treated.2

Primary Restless Legs Syndrome

Most affected individuals suffer from primary RLS, which shows a familial association in more than 50% of cases.17–19 Patients with familial RLS have an earlier onset of symptoms than do those suffering from the sporadic type, and the progression is slower. The relevant age at onset of the disease at which to subdivide patients with RLS into early- and late-onset groups remains to be investigated. One study revealed that patients who were younger than 45 years at onset have a greater probability of having an affected first-degree relative than do those who were older than 45 years at onset.20 In another study, early-onset RLS (with onset at younger than 30 years) has been found to be genetically different from late-onset RLS: In early-onset RLS, it was suggested that a major gene is segregating in an autosomal dominant mode of inheritance with an additional multifactorial component.19 Genomewide studies have been conducted to map genes that play a role in the vulnerability to RLS. So far, linkage was found to a chromosomal locus on 12q,21 which was not confirmed in four other families; on 14q,22 which was replicated in one family23; and on 9p.24 Inspection of huge pedigrees indicates anticipation and variable penetrance.25,26 Investigations of candidate gene coding for receptors and enzymes related to dopaminergic transmission27,28 revealed no differences in the genotypic or allelic distributions between RLS and control subjects.

Secondary Restless Legs Syndrome

Although most RLS cases may be idiopathic, RLS is often linked to other medical or neurological disorders. The most important associations of RLS are with end-stage renal disease29,30 and with iron deficiency.31,32 RLS may also develop during pregnancy33,34 or may intensify after treatment with various drugs. In many reports, RLS has been linked to dopamine antagonists, such as typical and atypical neuroleptics and metoclopramide, or to antidepressants, such as tricyclic and tetracyclic antidepressants, serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and lithium. Although supporting data are limited, peripheral neuropathies, such as axonal neuropathy,35 cryoglobulinemic neuropathy,36 familial amyloid polyneuropathy,37 Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2,38 and small-fiber neuropathies39 may be associated with RLS. Because the prevalence of RLS among patients with peripheral polyneuropathies has been shown to be only 5.2%40 and thus does not exceed that in the general population, this association is of unclear significance. Other neurological diseases that have been reported to be linked with RLS are radiculopathies41 and myelopathies, such as multiple sclerosis or syringomyelia.42 It has also been shown that some children who were diagnosed with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder may have PLMS or in fact suffer from RLS.43–45

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Although RLS pathophysiology is still unknown, knowledge about it has developed significantly, which has led to diverse hypotheses.46 The medication responses indicate that RLS results from abnormal functioning in the nervous system.47 Overall, the central nervous system areas involved in RLS pathophysiology are unknown, and the role of the peripheral nervous system, if any, is uncertain.48 Several studies have provided evidence that RLS is associated with peripheral neuropathy; therefore, it is possible that peripheral nerve lesions are a trigger for RLS.

Dopaminergic Function in Restless Legs Syndrome

Dopaminergic mechanisms are supposed to play an important role, particularly inasmuch as dopaminergic drugs have shown to be especially beneficial in RLS. In addition, the circadian manifestation of RLS symptoms coincides with lower levels of central dopamine activity.49 However, several investigations, including positron emission tomography and single photon emission computed tomography studies of the dopaminergic nigrostriatal system,50 cerebrospinal fluid analysis of dopaminergic metabolites,51,52 and even histopathological studies, have not provided evidence of a primary dopaminergic deficit or neurodegeneration in the basal ganglia53 that favors a functional impairment or a modulating effect of the dopaminergic system. The fact that melatonin secretion, which is increased at night, is correlated with the severity of RLS symptoms54 supports the dopamine hypothesis, inasmuch as melatonin exerts an inhibitory effect on central dopamine secretion. Daytime and nighttime melatonin excretion per se is normal in patients with RLS.55

Iron Metabolism in Restless Legs Syndrome

A strong negative correlation between serum ferritin levels and RLS severity,31,32 the therapeutic effect of iron in RLS,56 the reduction of iron in the substantia nigra as shown by magnetic resonance imaging,57 and reduced cerebrospinal fluid ferritin levels and increased cerebrospinal fluid transferrin levels58 in patients with RLS indicate that an impaired iron metabolism may be another important factor in the pathophysiology of RLS. Neuropathological investigations have shown that iron and heavy-ferritin staining was markedly decreased (and light-ferritin staining was strong) in the substantia nigra. In addition, transferrin receptor staining on neuromelanin-containing cells was decreased in brains of patients with RLS, whereas transferrin staining in these cells was increased.59 These data suggest that iron acquisition is compromised in neuromelanin cells, which may interfere with dopaminergic mechanisms.

Role of the Nociceptive System

Stiasny-Kolster and colleagues (2004)60 showed that the nociceptive system is involved in RLS pathophysiology. Patients with RLS exhibited a profound static mechanical hyperalgesia in response to punctate stimuli. This type of hyperalgesia improved significantly after long-term treatment with dopaminergic drugs. These findings suggests that RLS may be associated with central sensitization of spinal neurons, such as that in chronic neuropathic pain resulting from abnormal peripheral input and/or from altered descending inhibition (i.e., involving the supraspinal dopaminergic system). Thus, in addition to being a motor and sleep disorder, RLS may also be a pain disorder. These findings may also explain why substances that are well accepted for the treatment of neuropathic pain, such as opioids or anticonvulsants, alleviate RLS symptoms.

Localization of the Dysfunction

Regardless of the neurotransmitter systems and neurophysiological mechanisms involved in RLS pathophysiology, the site of the underlying neurological alteration is still unclear. Cortical involvement was previously considered unlikely because of the absence of cortical activity in functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) studies and the absence of a Bereitschaftspotential61 associated with the involuntary movements in RLS. Spectral power analysis of electroencephalographic studies, however, provides evidence that characteristic involuntary leg movements in RLS are preceded by a preparatory cortical activation. In addition, several neurophysiological studies with single or paired pulse stimulation showed a reduced intracortical inhibition62 and a shortened cortical silent period in patients with RLS.63,64 This cortical disinhibition may result from a shift in the balance of excitatory and inhibitory mechanisms toward either more excitability or less inhibition (e.g., as a result of increased sensory input or impaired subcortical mechanisms). Interestingly, levodopa (L-dopa) leads to a prolongation of the silent period and thus to an improvement of impaired inhibitory mechanisms.64 Some studies have suggested the involvement of subcortical areas in RLS pathophysiology. Lesions in the dopaminergic diencephalospinal tract (A11 neurons) have been proposed as an animal model for RLS65 and are discussed as potential underlying cause of RLS in humans.66 The effects of acute dopaminergic treatment on RLS symptoms and long-term dopaminergic treatment on static mechanical hyperalgesia support this suggestion. Thus, the dopaminergic system is either directly or indirectly involved in the central sensitization in RLS.60

The only fMRI investigations in patients with RLS conducted so far67 revealed a bilateral activation of the cerebellum and a contralateral activation of the thalamus during sensory symptoms. During the occurrence of PLMs and sensory symptoms, the patients showed additional activation in the red nuclei and brainstem close to the reticular formation. These results support aforementioned neurophysiological studies that suggested that subcortical cerebral generators are involved in the pathogenesis of RLS. During the combined condition (PLMs and sensory symptoms), the activation was still larger in the cerebellum than during each condition alone, which points to a neuronal participation of the cerebellum in the motor and sensory process as well. This finding is in agreement that in healthy subjects, the cerebellum is involved in sensory processing. When the distribution of the fMRI-activated cerebellar areas (subcortical in both hemispheres) were compared with histological autoradiographical studies of the human cerebellum, a similar distribution of opioid μ receptors could be detected. Thus, the cerebellum could be another possible site of interaction of opioidergic agents. The spinal cord may also play a major role in the pathophysiology of RLS. Patients with spinal cord lesions, particularly those with transsection of the spinal cord, often have PLMs, which suggests that PLMs are generated in the spinal cord.68–71 In these cases, however, the number of PLMs is lower and the circadian rhythmicity and the response to dopaminergic agents are less pronounced than in patients with RLS.69,72,73 Flexor reflex studies showed an increased spinal cord excitability during sleep in patients with RLS, which indicates that signal processing in the spinal cord is altered. In addition, the presence of mechanical hyperalgesia in RLS indicates central sensitization of spinal neurons. However, the central sensitization in RLS may also be based on afferent input-induced plasticity of spinal nociceptive transmission,74 and long-standing abnormal peripheral input may explain various kinds of secondary RLS: for example, RLS triggered by polyneuropathies. Thus, it is conceivable that at least in a subgroup of patients with RLS, peripheral lesions may represent a pathophysiological factor for the development or aggravation of RLS.

DIAGNOSTIC CRITERIA FOR RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME

RLS is a clinical diagnosis that relies entirely on the patient’s symptoms. According to international diagnostic criteria75 (Walters, 1995) and a consensus established by the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group76 (Allen et al, 2003) RLS is characterized by four essential criteria (Table 37-1). To make a definite diagnosis of RLS, all four diagnostic criteria must be established. In some cases, these criteria may be inadequate for ruling out conditions mimicking RLS, such as peripheral neuropathy, leg cramps, positional discomfort, or parkinsonian symptoms, inasmuch as these conditions may sometimes lead to positive answers referring to different problems. If these features are comorbid with RLS, it can, in turn, also be difficult to recognize RLS.

TABLE 37-1 Essential Diagnostic Criteria of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group

From Allen R, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al: Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from The Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology Workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med 2003; 4:101-119.

The following supportive features that are not necessary to make the diagnosis RLS but may, especially in doubtful cases, help to diagnose or exclude RLS have been established.76

Periodic Limb Movements in Sleep

PLMSs are reported to occur in 80% to 90% of patients with RLS. However, PLMS also commonly occur in other disorders and in the elderly. A PLMS index (number of PLMSs per hour of sleep) of greater than 5 is considered pathological, although data supporting this feature are very limited. The occurrence of PLMs during nocturnal periods of wakefulness (PLMW) is considered to be more specific for RLS.77 Thus, the presence of a high number of PLMs is supportive for RLS, but the absence of PLMs does not exclude RLS.

In addition to the essential and supportive criteria, the natural clinical course, the presence and character of sleep disturbances, and the physical examination findings are other features that may be helpful for diagnosis of RLS.76

Natural Clinical Course

RLS is usually a chronic disease, and symptoms typically increase over time. As mentioned, the age at onset of RLS varies widely, from childhood to 80 years of age and even older. Patients with early-onset RLS are more likely to have affected family members than are those with late-onset RLS.19 When RLS symptoms appear at a young age, the onset is more often insidious. RLS symptoms may be present intermittently for many years with fluctuating severity. Initially, mild RLS may occur in single nights, sometimes with or without sleep disturbances, or in aggravating situations during the day, such as during a long overseas flight. There may be long periods of remission, but the severity and frequency typically increase over time. Many patients with RLS experience their RLS as nightly events with difficulty falling asleep and several awakenings with walking around or other actions that may lead to temporary relief, such as taking a cold foot bath. Other patients progress to daily symptoms within several years. Many of these patients have disease onset in late adult life and have secondary RLS. The natural clinical course may be influenced by the development of augmentation as a result of medication side effects (see following discussion).

EVALUATION OF RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME

Medical History

When a patient meets the four essential diagnostic criteria and when mimicking conditions can be ruled out, the evaluation of RLS (Table 37-2) is minimal. In any case, however, a thorough medical history should be obtained with special attention to the time course, the appearance of symptoms during the 24-hour day, type and severity of sleep disturbances, and daytime vigilance. An atypical course of the disease with an abrupt onset and daily symptoms from the beginning may be suggestive of secondary forms of RLS. The time of RLS symptom onset during the day is important to know because medication intake should be individually tailored. Patients in whom severe RLS symptoms are already present in the late afternoon must take medication earlier than do patients with late-evening symptoms. Patients with problems initiating sleep may require other medication or another time of medication intake, in comparison with those who have problems maintaining sleep. It is also important to figure out why a patient’s sleep is disturbed. Even if RLS symptoms are adequately treated, sleep disturbances may remain if back pain or depression additionally interferes with sleep. A careful drug history should detect substances that may aggravate RLS or sleep disturbances. Thus, it is worthwhile to invest some time in a detailed history, particularly in the initial contact with an RLS patient.

Blood Tests

When evaluating patients with RLS, the clinician must look for factors that may exacerbate symptoms of RLS, because these may alter the treatment plan or make effective treatment more difficult to establish. With regard to laboratory findings, not only low iron but also low-normal serum ferritin levels (<50 μg/L) have been related to increased severity of RLS and may be associated with an increased risk of RLS even in patients with normal hemoglobin levels.31,32 Therefore, evaluation of serum iron and ferritin levels is strongly recommended as part of the medical evaluation for RLS, because these patients may benefit from iron supplements. When iron therapy is initiated, patients need to be routinely monitored to check the response to iron and to avoid iron overload. The iron storage disease hemochromatosis, which can coexist with RLS, requires special attention because it would be aggravated by iron supplementation.51,78 Other blood tests should be conducted, depending on the clinician’s reasonable suspicion, although it should be clear that patients are not in renal failure.

Polysomnographic Recordings

Sleep studies may be helpful in uncertain or complicated cases and if another sleep disorder such as sleep apnea is suspected. The presence of PLMs and, even more, of PLMSs associated with arousals supports the diagnosis of RLS.77 However, for the interpretation of polysomnographic recordings, it is important to consider that not all patients with RLS have PLM, that the presence and frequency of PLMs varies between nights, and that even patients with advanced RLS may have nights with nearly undisturbed sleep. Thus, the absence of PLMs does not preclude RLS. In addition, PLMSs can occur in a variety of disorders or even in normal individuals and are not specific for RLS. In the majority of these cases, however, PLMs are less frequent and less often associated with arousals. Although a higher number of PLMs are sometimes detected in sleep apnea, the arousals are caused mostly by the respiratory event. A sensitive technique must be used to monitor breathing during polysomnography, such as pressure transducer airflow monitoring or esophageal manometry, to reasonably rule out sleep-disordered breathing as the direct cause of the PLMSs.79 When PLMSs are independently present in a patient with sleep-disordered breathing and without a history of RLS, then a separate diagnosis of periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) may be considered if the PLMSs are still seen with adequate continuous positive airway pressure and if clinical sleep-wake disturbance that is not otherwise explained remains. In RLS, the number of PLMS arousals may be considered as a marker for the severity of the disease, which can be used for monitoring treatment effects. In general, polysomnographic recordings should be performed without drugs known to either suppress PLMs (e.g., dopaminergic drugs, opioids, anticonvulsants, benzodiazepines) or enhance PLMs (e.g., neuroleptics, antidepressants). Withdrawal of such medication, however, is often not possible and may also lead to a PLM rebound. In these cases, the significance of polysomnography is limited. Polysomnography during treatment may be helpful for optimizing therapy, for determining the reason for nonresponse, or if other sleep disturbances are suspected.

For differential diagnosis, PLMs can be examined not only during polysomnography but also in a provocative test called the suggested immobilization test.77,80 In this test, the subject is asked to sit quietly, typically for an hour, while leg movements, usually determined by EMG and subjective complaints, are monitored. Most patients with RLS experience greater sensory discomfort than do normal persons and have a fair number of movements, which fulfill criteria for PLMWs.80 A combination of increased discomfort during the suggested immobilization test and PLMWs during polysomnography (using optimal thresholds) has been reported to provide a better discrimination from control subjects than does any single measure, with a sensitivity of 82% and a specificity of 100%.80

Levodopa Test

The response to a single oral dose of L-dopa can be used in clinical practice to support the diagnosis RLS. This is of particular value in untreated patients, in patients in whom the initial therapeutic effect of dopaminergic substances is not reliably assessable (e.g., dosage unknown, inappropriate time of drug intake, no accurate statement from the patient), and particularly in patients with mild RLS in whom polysomnography frequently fails to detect PLMs. A combined dose of 100 mg of L-dopa with 25 mg of dopa decarboxylase inhibitor is taken after onset of the leg symptoms, independently of the time of day. The severity of the symptoms in the legs is rated by the patient before medication intake and afterwards for a period of about 1 to 2 hours on a visual analog scale (0 = no symptoms to 100 = very severe symptoms). A positive test result is defined as a 50% improvement at any time within 2 hours after administration. The L-dopa test has a sensitivity of 88% and a specificity of 100%; this means that 88% of patients with RLS have a positive test result (>50% improvement) and that all patients with leg symptoms that are not caused by RLS, such as peripheral neuropathy, have a negative test result (<50% improvement) with L-dopa. On the basis of this 50% cutoff criterion, 90% of cases can be correctly diagnosed with the L-dopa test. However, a negative test result, defined as less than 50% improvement, does not preclude RLS, inasmuch as some patients report only mild improvement with 100 mg of L-dopa. Complete nonresponse, particularly in hitherto untreated patients, strongly argues against RLS (Stiasny-Kolster et al).81

Severity Assessment

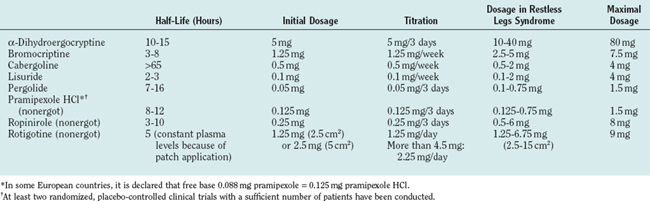

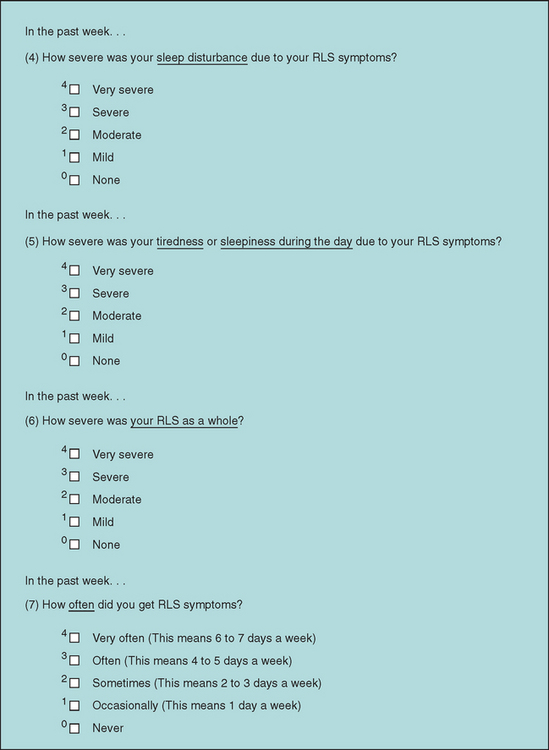

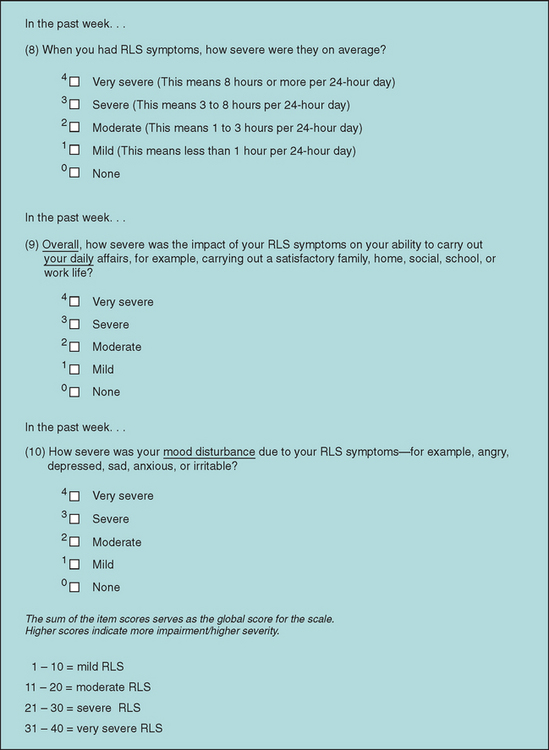

The severity of RLS may be quantified by the validated 10-item International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group Rating Scale (IRLS) (Fig. 37-1)82 (International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group, 2003) or the RLS-6 rating scales (Fig. 37-2).83 These scales are used in treatment trials to assess the therapeutic efficacy of drugs referring to the severity of RLS symptoms and sleep disturbances. The IRLS additionally addresses the frequency of RLS symptoms and the effect of RLS on quality of life. Both scales are easy to use in clinical practice.

Figure 37-1 International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group Rating Scale (IRLS). Walters AS, LeBrocq C, Dhar A, Hening W, Rosen R, Allen RP, Trenkwalder C; International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2003 Mar; 4(2):121-32. Copyright IRLS Study Group 2001. How to obtain the IRLS: Please contact the Information Resources Centre of Mapi Research Trust, 27 rue de la Villette, 69003 Lyon, FRANCE – Tel: +33(0)472 13 65 75 – Fax: +33(0)472 13 66 82 – Email: trust@mapi.fr – Internet: www.mapi-trust.org (conditions of use and (User)-agreement are provided). Useful information about the IRLS (such as references, translations available, scoring and others) is available on the Quality of Life Instrument Database (QOLID), available on the Internet at www.Qolid.org.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS OF RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME

Various conditions that may be similar to RLS need to be considered in the differential diagnosis (Table 37-3). However, most of them do not fulfill all four essential criteria for RLS or do not have a circadian variation with nocturnal accentuation. Restriction to rest may also be absent, and relief with movement may be either not present or only temporary with continued movement. Nocturnal leg cramps and polyneuropathy may meet all four diagnostic criteria of RLS. Nocturnal leg cramps are often unifocal; are associated with a contracted, indurated muscle; often occur in single attacks with subsequent relief; and are usually extremely painful. In peripheral neuropathy, particularly in small-fiber neuropathy, symptoms may be noticed more intensely in resting positions in the evening or during the night and may be experienced less with movement. However, these symptoms usually include the feet and are persistently present from the beginning, being mild initially and gradually increase in severity over time. Complete relief of pronounced symptoms is almost never reported. Peripheral neuropathy and sometimes somatic features of depression may be most difficult to delimit. Of course, it is possible that RLS could coexist with any mimicking conditions. Therefore, the presence of a mimicking disorder does not necessarily rule out RLS. Patients with PLMD have sleep fragmentation caused by PLM and consecutively have complaints of daytime sleepiness. To diagnose PLMD other causes of PLMS or associated disorders such as sleep apnea syndrome or RLS have to be ruled out. Sensory complaints and akathisia are fairly common in Parkinson’s disease,84 and lower limb restlessness may accompany wearing-off episodes in patients with motor fluctuations, thus mimicking RLS.85

TREATMENT

Nonpharmacological treatment consists of good sleep hygiene. Patients should be advised to avoid caffeine, alcohol, and heavy meals before going to bed. Bedtime hours should be regular and activity gradually reduced in the evening. Patients should sleep in a bedroom that should be used only for sleep or intimacy and not for watching television. In a next step, secondary causes of RLS should be excluded and/or associated disorders be primarily treated. The clinician should consider whether antidepressants, neuroleptic agents, or dopamine-blocking antiemetics such as metoclopramide may be contributing and whether discontinuation is possible without causing the patient harm. Successful kidney transplantation may lead to a complete remission in patients with RLS with renal insufficiency.17,86 Complete loss of all RLS symptoms in affected pregnant women after delivery is also frequently observed.33,87,88 The most important underlying cause may be iron deficiency. Iron supplementation has been shown to improve RLS in patients with iron deficiency31 but not in patients with normal iron levels.89 A common regimen is 325 mg of ferrous sulfate three times a day in combination with 100 to 200 mg of vitamin C with each dose to enhance absorption. Oral iron therapy can cause obstipation and abdominal discomfort, and the dosage may need to be reduced in some patients. Iron tablets are ideally taken on an empty stomach to enhance absorption, but if gastrointestinal symptoms develop, they should be taken with food. Iron should not be prescribed empirically because it may result in iron overload. Magnesium supplements may be beneficial in patients with mild RLS.90 Taking 12.4 mmol of magnesium in the evening has been shown to be beneficial in patients with a postulated magnesium deficiency in an open trial.91 There are no controlled studies that have shown a beneficial effect of other supplements such as zinc, vitamin B1, vitamin B12, vitamin E, or vitamin C.

Levodopa

According to Hening and colleagues (2004), if pharmacological therapy is initiated, dopaminergic agents are considered the first-line agents for treatment of RLS.92 In September 2000, L-Dopa/benserazide (Restex and Restex retard) became the first drug licensed for RLS, in two European countries, Germany and Switzerland.93–95 Doses of 50/12.5 to 100/25 mg of standard L-dopa/dopadecarboxylase inhibitor improve RLS symptoms about 1 hour after drug intake, resulting in an improved quality of sleep. In correlation to the plasma half-life of L-dopa (1 to 2 hours), the beneficial effect decreases, and RLS may persist into the second half of the night. If so, an additional dose of slow-release L-dopa/dopadecarboxylase inhibitor (100/25 mg given in combination with standard L-dopa/benserazide 1 hour before or at bedtime) is recommended.94 In general, L-dopa is best used by patients with mild RLS. The immediate response to L-dopa without a long titration period is appreciated by the patient and indicates to the treating physician that the diagnosis is correct. In patients with sporadic RLS, L-dopa can be given on demand. Pills are generally taken at bedtime, perhaps supplemented by a dose earlier in the day to control evening or daytime symptoms. For maximal absorption, L-dopa should not be taken with high-protein foods.

In more severely affected patients, RLS symptoms may not be adequately controlled for the whole night even with the combination of standard and slow-release preparations. These patients benefit from a dopamine agonist. In others, RLS symptoms may shift to the early evening or daytime, become more intense, or involve other body parts after L-dopa therapy has been started. This phenomenon has been called augmentation.96 Consequently, these patients are frequently treated with multiple and higher dosages of L-dopa throughout the 24 hours to control RLS symptoms. If L-dopa therapy is complicated by augmentation, L-dopa should be completely substituted by a dopamine agonist. Because augmentation seems to be more frequent in patients with higher L-dopa dosages, maximum dosages of 300 to 400 mg should not be exceeded. It is also possible that augmentation may be triggered if patients are treated with higher L-dopa dosages than are needed or if daily L-dopa therapy is recommended although symptoms appear only intermittently. Therefore, in some patients with mild symptoms, 50 mg L-dopa, perhaps on demand, may be sufficient.

Dopamine Agonists

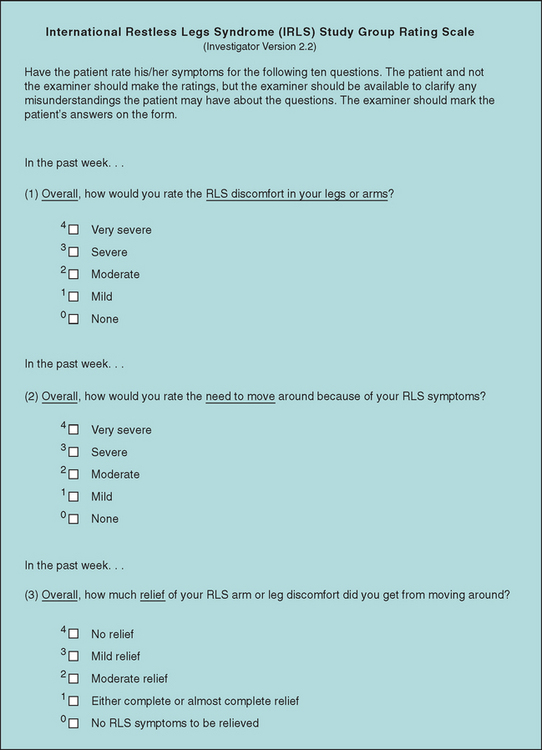

Because of their longer half-lives and fewer problems (at least according to current clinical observations) with augmentation, dopamine agonists are preferred especially in patients with advanced daily RLS. Given once in the early evening—in dosages that are usually lower than those for Parkinson’s disease—dopamine agonists cover sensory and motor symptoms of RLS throughout the night. As a consequence, sleep and quality of life markedly improve in most patients. To date, several large-scale placebo-controlled trials with dopamine agonists with the goal of approval by the European Medicines Agency or the U.S. Food and Drug Administration have been performed. Convincing data are available for the dopamine agonists cabergoline,97–99 pergolide,100–102 ropinirole,102,103 and pramipexole104,105 and the dopamine agonist patch rotigotine.106 Apart from general considerations, several factors determine the physician’s decision about a certain substance and its dosage, such as the half-life, the duration of upward titration, the structure (nonergot or ergot), individual efficacy and tolerability, and, the physician’s experience with regard to a single dopamine agonist. Shorter-acting dopamine agonists may necessitate twice-daily doses, with an earlier dose in the late afternoon and a second dose in the evening. With longer acting dopamine agonists, a single evening dose (2 to 3 hours before bedtime) is sufficient. If insomnia remains to a considerable degree even though sensorimotor symptoms are well controlled by the dopaminergic drug, other factors and possibly other treatment options must be considered. Characteristics of various dopamine agonists are given in Table 37-4.

Other Substances

Opioids have shown to be effective in RLS, and their analgesic or sedative effect may be advantageous in individual patients, but data from placebo-controlled trials are very limited and available for only oxycodone.107 Opioids may be highly effective particularly in advanced RLS and should not be withheld from appropriate patients because of fear of potential development of tolerance or dependence. Escalation of dosage is rare, as is dependence in the absence of a history of substance abuse. If opioids are used, treatment regimens like those for in chronic pain syndromes should be applied. Severely affected patients in particular may profit from opioid patch applications. To avoid constipation, lactulose should be added to the regimen from the beginning.

Gabapentin may be an alternative choice, particularly for less intense RLS, for RLS perceived as painful, for RLS in combination with a painful peripheral neuropathy, or for an unrelated chronic pain syndrome. Gabapentin should be used in once- or twice-daily doses in the late afternoon or evening (one third of the dose) or before sleep (two thirds of the dose). Treatment should commence with 300 mg per dose or even less because of the possible tendency to cause somnolence and gait unsteadiness, especially in elderly patients. A controlled trial has shown that a mean dosage of 1800 mg/day is needed for efficacy.108 The anticonvulsants carbamazepine and valproic acid seem to be less effective against RLS than gabapentin. Other anticonvulsants with antinociceptive effect are currently under investigation in patients with RLS.

Allen R, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the restless legs syndrome diagnosis and epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

Hening WA, Allen RP, Earley CJ, et al. An update on the dopaminergic treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine interim review. Sleep. 2004;27:560-583.

The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs. Sleep Med. 2003;4:121-132.

Stiasny-Kolster et al Stiasny-Kolster K, Kohnen R, Möller JC, Trenkwalder C, et al: Validation of the “L-dopa test” for diagnosis of restless legs syndrome. MOV Disord in press.

Stiasny-Kolster K, Magerl W, Oertel WH, et al. Static mechanical hyperalgesia without dynamic tactile allodynia in patients with restless legs syndrome. Brain. 2004;127:773-782.

Walters AS. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634-642.

1 Ekbom KA. Restless legs syndrome. Acta Med Scand. 1945;158(Suppl):4-122.

2 Hening W, Walters AS, Allen RP, et al. Impact, diagnosis and treatment of restless legs syndrome (RLS) in a primary care population: the REST (RLS epidemiology, symptoms, and treatment) primary care study. Sleep Med. 2004;5:237-246.

3 Allen RP, Earley CJ. Restless legs syndrome: a review of clinical and pathophysiologic features. J Clin Neurol. 2001;18:128-147.

4 Winkelmann J, Prager M, Lieb R, et al. “Anxietas tibiarum.” Depression and anxiety disorders in patients with restless legs syndrome. J Neurol. 2005;252:67-71.

5 Sevim S, Dogu O, Kaleagasi H, et al. Correlation of anxiety and depression symptoms in patients with restless legs syndrome: a population based survey. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:226-230.

6 Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Poirier G, et al. Clinical, polysomnographic, and genetic characteristics of restless legs syndrome: a study of 133 patients diagnosed with new standard criteria. Mov Disord. 1997;12:61-65.

7 Smith RC. Relationship of periodic movements in sleep (nocturnal myoclonus) and the Babinski sign. Sleep. 1985;8:239-243.

8 Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome among men aged 18 to 64 years: an association with somatic disease and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Mov Disord. 2001;16:1159-1163.

9 Rothdach AJ, Trenkwalder C, Haberstock J, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of RLS in an elderly population: the MEMO study. Memory and Morbidity in Augsburg Elderly. Neurology. 2000;54:1064-1068.

10 Phillips B, Young T, Finn L, et al. Epidemiology of restless legs syndrome in adults. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:2137-2141.

11 Ulfberg J, Nystrom B, Carter N, et al. Restless legs syndrome among working-aged women. Eur Neurol. 2001;46:17-19.

12 Högl B, et al. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome in the central European alpine region of South Tyrol. Sleep. 2003;26:A344.

13 Berger K, Luedemann J, Trenkwalder C, et al. Sex and the risk of restless legs syndrome in the general population. Arch Intern Med. 2004;164:196-202.

14 Kageyama T, Kabuto M, Nitta H, et al. Prevalences of periodic limb movement–like and restless legs–like symptoms among Japanese adults. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2000;54:296-298.

15 Ohayon MM, Roth T. Prevalence of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder in the general population. J Psychosom Res. 2002;53:547-554.

16 Walters AS, Hickey K, Maltzman J, et al. A questionnaire study of 138 patients with restless legs syndrome: the “Night-Walkers” survey. Neurology. 1996;46:92-95.

17 Stautner A, Stiasny K, Collado-Seidel V, et al. Comparison of idiopathic and uremic restless legs syndrome: results of a database of 134 patients [Abstract]. Mov Disord. 1996;11(Suppl):98.

18 Ondo W, Jankovic J. Restless legs syndrome: clinicoetiologic correlates. Neurology. 1996;47:1435-1441.

19 Winkelmann J, Muller-Myhsok B, Wittchen HU, et al. Complex segregation analysis of restless legs syndrome provides evidence for an autosomal-dominant mode of inheritance in early age at onset families. Ann Neurol. 2002;52:279-302.

20 Allen RP, Earley CJ. Defining the phenotype of the restless legs syndrome (RLS) using age-of-symptom-onset. Sleep Med. 2000;1:11-19.

21 Desautels A, Turecki G, Montplaisir J, et al. Identification of a major susceptibility locus for restless legs syndrome on chromosome 12q. Am J Hum Genet. 2001;69:1266-1270.

22 Bonati MT, Ferini-Strambi L, Aridon P, et al. Autosomal dominant restless legs syndrome maps on chromosome 14q. Brain. 2003;126(Pt 6):1485-1492.

23 Levchenko A, Montplaisir JY, Dube MP, et al. The 14q restless legs syndrome locus in the French Canadian population. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:887-891.

24 Chen S, Ondo WG, Rao S, et al. Genomewide linkage scan identifies a novel susceptibility locus for restless legs syndrome on chromosome 9p. Am J Hum Genet. 2004;74:876-885.

25 Trenkwalder C, Seidel VC, Gasser T, et al. Clinical symptoms and possible anticipation in a large kindred of familial restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1996;11:389-394.

26 Lazzarini A, Walters AS, Hickey K, et al. Studies of penetrance and anticipation in five autosomal-dominant restless legs syndrome pedigrees. Mov Disord. 1999;14:111-116.

27 Desautels A, Turecki G, Montplaisir J, et al. Dopaminergic neurotransmission and restless legs syndrome: a genetic association analysis. Neurology. 2001;57:1304-1306.

28 Dichgans M, Walther E, Collado-Seidel V, et al. Autosomal-dominant restless legs syndrome: genetics model and evaluation of 22 candidate genes. Mov Disord. 1996;11:87.

29 Collado-Seidel V, Kohnen R, Samtleben W, et al. Clinical and biochemical findings in uremic patients with and without restless legs syndrome. Am J Kidney Dis. 1998;31:324-328.

30 Gigli GL, Adorati M, Dolso P, et al. Restless legs syndrome in end-stage renal disease. Sleep Med. 2004;5:309-315.

31 O’Keeffe ST, Gavin K, Lavan JN. Iron status and restless legs syndrome in the elderly. Age Ageing. 1994;23:200-203.

32 Sun ER, Chen CA, Ho G, et al. Iron and the restless legs syndrome. Sleep. 1998;21:371-377.

33 McParland P, Pearce JM. Restless legs syndrome in pregnancy. Case reports. Clin Exp Obstet Gynecol. 1990;17:5-6.

34 Manconi M, Govoni V, De Vito A, et al. Restless legs syndrome and pregnancy. Neurology. 2004;63:1065-1069.

35 Iannaccone S, Zucconi M, Marchettini P, et al. Evidence of peripheral axonal neuropathy in primary restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 1995;10:2-9.

36 Gemignani F, Marbini A, Di Giovanni G, et al. Cryoglobulinaemic neuropathy manifesting with restless legs syndrome. J Neurol Sci. 1997;152:218-223.

37 Salvi F, Montagna P, Plasmati R, et al. Restless legs syndrome and nocturnal myoclonus: initial clinical manifestation of familial amyloid polyneuropathy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990;53:522-525.

38 Gemignani F, Marbini A, Di Giovanni G, et al. Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease type 2 with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:1064-1066.

39 Polydefkis M, Allen RP, Hauer P, et al. Subclinical sensory neuropathy in late-onset restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2000;55:1115-1121.

40 Rutkove SB, Matheson JK, Logigian EL. Restless legs syndrome in patients with polyneuropathy. Muscle Nerve. 1996;19:670-672.

41 Walters AS, Wagner M, Hening WA. Periodic limb movements as the initial manifestation of restless legs syndrome triggered by lumbosacral radiculopathy [Letter]. Sleep. 1996;19:825-826.

42 Winkelmann J, Wetter TC, Trenkwalder C, et al. Periodic limb movements in syringomyelia and syringobulbia. Mov Disord. 2000;15:752-755.

43 Chervin RD, Archbold KH, Dillon JE, et al. Associations between symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, restless legs, and periodic leg movements. Sleep. 2002;25:213-218.

44 Walters AS, Mandelbaum DE, Lewin DS, et al. Dopaminergic therapy in children with restless legs/periodic limb movements in sleep and ADHD. Dopaminergic Therapy Study Group. Pediatr Neurol. 2000;22:182-186.

45 Picchietti DL, Underwood DJ, Farris WA, et al. Further studies on periodic limb movement disorder and restless legs syndrome in children with attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mov Disord. 1999;14:1000-1007.

46 Trenkwalder C, Paulus W. Why do restless legs occur at rest?—Pathophysiology of central and peripheral structures in RLS. Neurophysiology of RLS (part 2). Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:1975-1988.

47 Winkelmann J, Schadrack J, Wetter TC, et al. Opioid and dopamine antagonist drug challenges in untreated restless legs syndrome patients. Sleep Med. 2001;2:57-61.

48 Happe S, Zeitlhofer J. Abnormal cutaneous thermal thresholds in patients with restless legs syndrome. J Neurol. 2003;250:362-365.

49 Sowers JR, Vlachakis N. Circadian variation in plasma dopamine levels in man. J Endocrinol Invest. 1984;7:341-345.

50 Garcia-Borreguero D, Odin P, Schwarz C. Restless legs syndrome: an overview of the current understanding and management. Acta Neurol Scand. 2004;109:303-317.

51 Earley CJ, Hyland K, Allen RP. CSF dopamine, serotonin, and biopterin metabolites in patients with restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2001;16:144-149.

52 Stiasny-Kolster K, Moller JC, Zschocke J, et al. Normal dopaminergic and serotonergic metabolites in cerebrospinal fluid and blood of restless legs syndrome patients. Mov Disord. 2004;19:192-196.

53 Pittock SJ, et al. Neuropathology of primary restless legs syndrome: Absence of specific tau- and alpha-synuclein pathology. Mov Disord. 2004;19(6):695-699.

54 Michaud M, et al. Circadian rhythm of restless legs syndrome: relationship with biological markers. Ann Neurol. 2004;55:372-380.

55 Tribl SJ, Waldhauser F, Sycha T, et al. Urinary 6-hydroxymelatonin-sulfate excretion and circadian rhythm in patients with restless legs syndrome. J Pineal Res. 2003;35:295-296.

56 Earley CJ, Heckler D, Allen RP. The treatment of restless legs syndrome with intravenous iron dextran. Sleep Med. 2004;5:231-235.

57 Allen RP, Barker PB, Wehrl F, et al. MRI measurement of brain iron in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56:263-265.

58 Earley CJ, Connors JR, Allen RP. RLS patients have abnormal reduced CSF ferritin compared to normal controls. Neurology. 1999;52(Suppl 2):A111-A112.

59 Connor JR, Wang XS, Patton SM, et al. Decreased transferrin receptor expression by neuromelanin cells in restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2004;62:1563-1567.

60 Stiasny-Kolster K, Magerl W, Oertel WH, et al. Static mechanical hyperalgesia without dynamic tactile allodynia in patients with restless legs syndrome. Brain. 2004;127:773-782.

61 Trenkwalder C, Bucher SF, Oertel WH, et al. Bereitschaftspotential in idiopathic and symptomatic restless legs syndrome. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1993;89:95-103.

62 Tergau F, Wischer S, Paulus W. Impaired motor cortex excitability in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1998;50:A223.

63 Entezari-Taher M, Singleton JR, Jones CR, et al. Changes in excitability of motor cortical circuitry in primary restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;53:1201-1205.

64 Stiasny-Kolster K, Haeske H, Tergau F, et al. Cortical silent period is shortened in restless legs syndrome independently from circadian rhythm. Suppl Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;56:381-389.

65 Ondo W. Clinical correlates of 6-hydroxydopamine injections into A11 dopaminergic neurons in rats: a possible model for restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2000;15:154-158.

66 Akpinar S. The primary restless legs syndrome pathogenesis depends on the dysfunction of EEG alpha activity. Med Hypotheses. 2003;60:190-198.

67 Bucher SF, Seelos KC, Oertel WH, et al. Cerebral generators involved in the pathogenesis of the restless legs syndrome. Ann Neurol. 1997;41:639-645.

68 de Mello MT, et al. Incidence of periodic leg movements and of the restless legs syndrome during sleep following acute physical activity in spinal cord injury subjects. Spinal Cord. 1996;34(5):294-296.

69 de Mello MT, Poyares DL, Tufik S. Treatment of periodic leg movements with a dopaminergic agonist in subjects with total spinal cord lesions. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:634-637.

70 Dickel MJ, Renfrow SD, Moore PT, et al. Rapid eye movement sleep periodic leg movements in patients with spinal cord injury. Sleep. 1994;17:733-738.

71 Yokota T, Hirose K, Tanabe H, et al. Sleep related periodic leg movements (nocturnal myoclonus) due to spinal cord lesion. J Neurol Sci. 1991;104:13-18.

72 Culpepper WJ, Badia P, Shaffer JI. Time-of-night patterns in PLMS activity. Sleep. 1992;15:306-311.

73 Pollmächer T, Schulz H. Periodic leg movements (PLM): their relationship to sleep stages. Sleep. 1993;16:572-577.

74 Sandkühler J. Learning and memory in pain pathways. Pain. 2000;88:113-118.

75 Walters AS. Toward a better definition of the restless legs syndrome. The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Mov Disord. 1995;10:634-642.

76 Allen R, Picchietti D, Hening WA, et al. Restless legs syndrome: diagnostic criteria, special considerations, and epidemiology. A report from the Restless Legs Syndrome Diagnosis and Epidemiology workshop at the National Institutes of Health. Sleep Med. 2003;4:101-119.

77 Montplaisir J, Boucher S, Nicolas A, et al. Immobilization tests and periodic leg movements in sleep for the diagnosis of restless leg syndrome. Mov Disord. 1998;13:324-329.

78 Barton JC, Wooten VD, Acton RT. Hemochromatosis and iron therapy of restless legs syndrome. Sleep Med. 2001;2:249-251.

79 Exar EN, Collop NA. The association of upper airway resistance syndrome. Sleep. 2001;24:188-192.

80 Michaud M, Lavigne G, Desautels A, et al. Effects of immobility on sensory and motor symptoms of restless legs syndrome. Mov Disord. 2002;17:112-115.

81 Stiasny-Kolster K, Kohnen R, Möller JC, Treukwalder C, et al: Validation of the “L-dopa test” for diagnosis of restless legs syndrome. MOV Disord in press.

82 The International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group. Validation of the International Restless Legs Syndrome Study Group rating scale for restless legs. Sleep Med. 2003;4:121-132.

83 Kohnen R, Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, et al. Severity rating of restless legs syndrome: review of ten years experience with the RLS-6 scales in clinical trials. Sleep. 2003;26:A342.

84 Lang AE, Johnson K. Akathisia in idiopathic Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 1987;37:477-481.

85 Poewe W, Högl B. Akathisia, restless legs and periodic limb movements in sleep in Parkinson’s disease. Neurology. 2004;63(Suppl 3):S12-S16.

86 Yasuda T, Nishimura A, Katsuki Y, et al. Restless legs syndrome treated successfully by kidney transplantation—a case report. Clin Transpl. 1986;12:138.

87 Goodman JD, Brodie C, Ayida GA. Restless leg syndrome in pregnancy. BMJ. 1988;297:1101-1102.

88 Lee KA, Zaffke ME, Baratte-Beebe K. Restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance during pregnancy: the role of folate and iron. J Womens Health Gend Based Med. 2001;10:335-341.

89 Davis BJ, Rajput A, Rajput ML, et al. A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial of iron in restless legs syndrome. Eur Neurol. 2000;43:70-75.

90 Silber MH, Ehrenberg BL, Allen RP, et al. An algorithm for the management of restless legs syndrome. Mayo Clin Proc. 2004;79:916-922.

91 Hornyak M, Voderholzer U, Hohagen F, et al. Magnesium therapy for periodic leg movements–related insomnia and restless legs syndrome: an open pilot study. Sleep. 1998;21:501-505.

92 Hening WA, Allen RP, Earley CJ, et al. An update on the dopaminergic treatment of restless legs syndrome and periodic limb movement disorder. An American Academy of Sleep Medicine interim review. Sleep. 2004;27:560-583.

93 Trenkwalder C, Stiasny K, Pollmacher T, et al. L-Dopa therapy of uremic and idiopathic restless legs syndrome: a double-blind, crossover trial. Sleep. 1995;18:681-688.

94 Collado-Seidel V, Kazenwadel J, Wetter TC, et al. A controlled study of additional SR-L-dopa in L-dopa responsive RLS with late night symptoms. Neurology. 1999;52:285-290.

95 Benes H, Kurella B, Kummer J, et al. Rapid onset of action of levodopa in restless legs syndrome: a double-blind, randomized, multicenter, crossover trial. Sleep. 1999;22:1073-1081.

96 Allen RP, Earley CJ. Augmentation of the restless legs syndrome with carbidopa/levodopa. Sleep. 1996;19:205-213.

97 Stiasny K, Robbecke J, Schuler P, et al. Treatment of idiopathic restless legs syndrome (RLS) with the D2-agonist cabergoline—an open clinical trial. Sleep. 2000;23:349-354.

98 Stiasny-Kolster K, Benes H, Peglau I, et al. Effective cabergoline treatment in idiopathic restless legs syndrome (RLS). Neurology. 2004;63:2272-2279.

99 Oertel WH, Benes H, Happe S, et al. Efficacy of cabergoline for the treatment of sensorimotor symptoms and sleep disturbances in restless legs syndrome: A placebo-controlled, 5-week, double-blind, randomized, multicenter, polysomnographic study. Mov Disord. 2004;19(Suppl. 9):S425.

100 Wetter TC, Stiasny K, Winkelmann J, et al. A randomized controlled study of pergolide in patients with restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 1999;52:944-950.

101 Stiasny K, Wetter TC, Winkelmann J, et al. Long-term effects of pergolide in the treatment of restless legs syndrome. Neurology. 2001;56:1399-1402.

102 Trenkwalder C, Garcia-Borreguero D, Montagna P, et al. Ropinirole in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: results from the TREAT RLS 1 study, a 12 week, randomised, placebo controlled study in 10 European countries. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:92-97.

103 Walters AS, Ondo WG, Dreykluft T, et al. Ropinirole is effective in the treatment of restless legs syndrome: TREAT RLS 2: a 12-week double-blind, randomized, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1414-1423.

104 Montplaisir J, Nicolas A, Denesle R, et al. Restless legs syndrome improved by pramipexole: a double-blind randomized trial. Neurology. 1999;52:938-943.

105 Oertel WH, Stiasny-Kolster K, Bergtholdt B, et al: Efficacy of Pramipexole in restless legs syndrome: a 6-week, multicenter, randomize, double-blind study. Submitted for publication.

106 Stiasny-Kolster K, Kohnen R, Schollmayer E, et al. Patch-application of the dopamine agonist rotigotine to patients with moderate to advanced stages of restless legs syndrome—a double-blind placebo-controlled pilot study. Mov Disord. 2004;19:1432-1438.

107 Walters AS, Wagner ML, Hening WA, et al. Successful treatment of the idiopathic restless legs syndrome in a randomized double-blind trial of oxycodone versus placebo. Sleep. 1993;16:327-332.

108 Garcia-Borreguero D, Larrosa O, de la Llave Y, et al. Treatment of restless legs syndrome with gabapentin: a double-blind, crossover study. Neurology. 2002;59:1573-1579.