Chapter 435 Tumors of the Heart

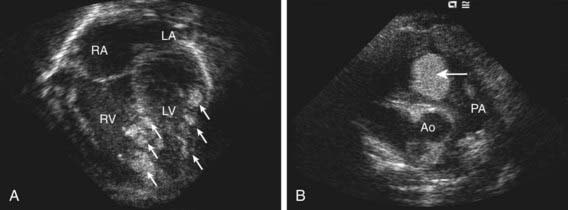

The vast majority of tumors originating from the heart are benign. Rhabdomyomas are the most common pediatric cardiac tumors and are associated with tuberous sclerosis in 70-95% of cases (Chapter 589.2). Rhabdomyomas may occur at any age, from fetal life through late adolescence. They are often multiple, can occur in any cardiac chamber, and originate within the myocardium extending, often, into the atrial or ventricular cavities (Fig. 435-1). Depending on their location and size, they can result in inflow or outflow obstruction leading to cyanosis or cardiac failure. Atrial and ventricular arrhythmias have been reported with rhabdomyomas, and on occasion, ventricular pre-excitation (Wolff-Parkinson-White) is present on ECG.

Burke A, Virmani R. Pediatric heart tumors. Cardiovasc Pathol. 2008;17:193-198.

Gunther T, Schreiber C, Noebauer C, et al. Treatment strategies for pediatric patients with primary cardiac and pericardial tumors: a 30-year review. Pediatr Cardiol. 2008;29:1071-1076.

Jozwiak S, Kotulska K, Kasprzyk-Obara J, et al. Clinical and genotype studies of cardiac tumors in 154 patients with tuberous sclerosis complex. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e1146-e1151.

Uzun O, Wilson D, Vujanic G, et al. Cardiac tumors in children. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:11.

Wu K, Mo X, Liu Y. Clinical analysis and surgical results of cardiac myxoma in pediatric patients. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:48-50.