Chapter 198 Tularemia (Francisella tularensis)

Tularemia is a zoonotic infection caused by the gram-negative bacterium Francisella tularensis. Tularemia is primarily a disease of wild animals; human disease is incidental and usually results from contact with blood-sucking insects or live or dead wild animals. The illness caused by F. tularensis is manifested by different clinical syndromes, the most common of which consists of an ulcerative lesion at the site of inoculation with regional lymphadenopathy or lymphadenitis. It is also a potential agent of bioterrorism (Chapter 704).

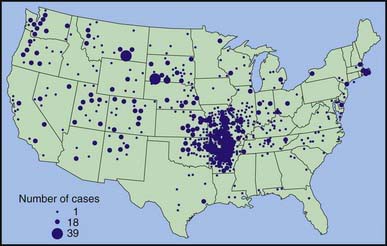

Epidemiology

During 1990-2000, a total of 1,368 cases of tularemia were reported in the USA from 44 states, averaging 124 cases (range 86-193) per year (Fig. 198-1). Four states accounted for 56% of all reported tularemia cases: Arkansas, 315 cases (23%); Missouri, 265 cases (19%); South Dakota, 96 cases (7%); and Oklahoma, 90 cases (7%).

Clinical Manifestations

Although it may vary, the average incubation period from infection until clinical symptoms appear is 3 days (range, 1-21 days). A sudden onset of fever with other associated symptoms is common (Table 198-1). Physical examination may include lymphadenopathy, hepatosplenomegaly, or skin lesions. Various skin lesions have been described, including erythema multiforme and erythema nodosum. Approximately 20% of patients may develop a generalized maculopapular rash that occasionally becomes pustular. These clinical manifestations of tularemia have been divided into various syndromes (Table 198-2).

Table 198-1 COMMON CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF TULAREMIA IN CHILDREN

| SIGN OR SYMPTOM | FREQUENCY (%) |

|---|---|

| Lymphadenopathy | 96 |

| Fever (>38.3°C) | 87 |

| Ulcer/eschar/papule | 45 |

| Pharyngitis | 43 |

| Myalgias/arthralgias | 39 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 35 |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 35 |

Table 198-2 CLINICAL SYNDROMES OF TULAREMIA IN CHILDREN

| CLINICAL SYNDROME | FREQUENCY (%) |

|---|---|

| Ulceroglandular | 45 |

| Glandular | 25 |

| Pneumonia | 14 |

| Oropharyngeal | 4 |

| Oculoglandular | 2 |

| Typhoidal | 2 |

| Other* | 6 |

* Includes meningitis, pericarditis, hepatitis, peritonitis, endocarditis, and osteomyelitis.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tularemia—Missouri, 2000–2007. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2009;58:744-748.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tularemia transmitted by insect bites, Wyoming, 2001–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:170-173.

Eisen RJ, Mead PS, Meyer AW, et al. Ecoepidemiology of tularemia in the southcentral United States. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2008;78:586-594.

Eliasson H, Broman T, Forsman M, et al. Tularemia: current epidemiology and disease management. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2006;20:289-311.

Kugeler KJ, Mead PS, Janusz AM, et al. Molecular epidemiology of Francisella tularensis in the United States. Clin Infect Dis. 2009;48:863-870.

Nigrovic LE, Wingerter SL. Tularemia. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2008;22:489-504.

Sjöstedt A. Tularemia: History, epidemiology, pathogen physiology, and clinical manifestations. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1105:1-29.

Tärnvik A, Chu MC. New approaches to diagnosis and therapy of tularemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2007;1105:378-404.