40 Tuberculosis

Introduction

Clinical and public health practice for bringing TB under control in the UK is underpinned by guidance from National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2006) and the Joint Committee on Vaccination and Immunisation (Department of Health, 2006).

Aetiology

TB is caused by tubercle bacilli, which belong to the genus Mycobacterium. These form a large group but only three relatives are obligate parasites that can cause TB disease. They are part of the Mycobacterium tuberculosis complex. The UK data for 2008 show that M. tuberculosis was isolated in 99% of confirmed cases, M. bovis in 0.4% and M. africanum in 0.5% that year (Health Protection Agency, 2009).

Clinical aspects

Infection with tubercle bacilli occurs in the vast majority of cases by the respiratory route. The lung lesions caused by infection commonly heal, leaving no residual changes except occasional pulmonary or tracheobronchial lymph node calcification (Heymann, 2004). About 5% of those initially infected will develop active primary disease (Hawker et al., 2005). This can include pulmonary disease, through local progression in the lungs, or by lymphatic or haematogenous spread of bacilli, to pulmonary, meningeal or other extrapulmonary involvement, or lead to disseminated disease (miliary TB). In the other 95%, the primary lesion heals without intervention but in at least one-half of patients, the bacilli survive in a latent form, which may then reactivate later in life. Infants, adolescents and immunosuppressed people are more susceptible to the more serious forms of TB such as miliary or meningeal TB.

Transmission

Transmission occurs through exposure to tubercle bacilli in air-borne droplet nuclei produced by people with pulmonary or respiratory tract TB during expiratory efforts such as coughing or sneezing. In general, only the respiratory forms of TB (tuberculosis of the larynx is highly contagious but rarely seen in the UK) are infectious. Most infections are acquired from adults with post-primary pulmonary TB. The greatest risk of infection is to close, prolonged contacts, mainly household contacts. Between 90% and 95% of cases of TB in children are non-infectious (Davies, 2003). TB cannot be acquired from individuals with latent TB infection (LTBI).

Patients should be considered infectious if they have sputum smear-positive pulmonary disease (i.e. they produce sputum containing sufficient tubercle bacilli to be seen on microscopic examination of a sputum smear) or laryngeal TB. Patients with smear-negative pulmonary disease (three sputum samples) are less infectious than those who are smear positive. The relative transmission rate from smear-negative compared with smear-positive patients has been estimated to be 0.22 (British Thoracic Society, 2000).

Risk groups

Certain groups are at increased risk of LTBI and possibly TB disease if exposed. These include:

People with certain medical conditions are at increased risk of developing active TB if they have LTBI. These medical risk factors are set out in Box 40.1.

Epidemiology

Global

Globally, it is estimated that TB causes about 2 million deaths worldwide each year. One-third of the world’s population is infected with the tubercle bacillus. It is becoming the leading cause of death among HIV-positive people. Over 4 million cases of TB disease are notified annually although the estimated number of new cases is put at 9 million. The majority of cases occur in poor countries in the southern hemisphere (WHO, 2009).

The numbers of cases estimated to have occurred in 2008, globally and by WHO region, is presented in Table 40.1. Most cases of TB are in South East Asia, although the highest rates are in Africa.

Table 40.1 Estimated epidemiological burden of tuberculosis incidence globally and by WHO region (Source: WHO, 2010)

| WHO region | Numbers (000s), 2008 (lower and upper bounds) | Rates per 100,000 population, 2008 (lower and upper bounds) |

|---|---|---|

| Africa | 2800 (2700–3000) | 350 (330–370) |

| Americas | 280 (260–300) | 31 (29–33) |

| Eastern Mediterranean | 650 (580–740) | 110 (99–130) |

| Europe | 430 (400–460) | 48 (45–51) |

| South-East Asia | 3200 (2800–3700) | 180 (160–210) |

| Western Pacific | 1900 (1700–2200) | 110 (95–130) |

| Global | 9400 (8900–9900) | 140 (130–150) |

In 2008, it was estimated that 440,000 people had MDR-TB worldwide, and one-third of these died. The brunt of the MDR-TB epidemic is borne by Asia, with almost 50% of cases worldwide estimated to occur in China and India. However, in some areas of the world, up to one in four people have drug-resistant TB. For example, 28% of all people newly diagnosed with TB in one region of North-Western Russia had the multidrug-resistant form of the disease (WHO, 2010).

UK

A total of 8655 cases were reported in 2008 (Health Protection Agency, 2009). The overall rate across all population groups was 14.1 per 100,000 population. Of all cases, 39% occurred in the London region, where the rate was 44.3 per 100,000 population. Nineteen primary care organisations in England had a rate of 40 per 100,000 or over, all of which were in major urban areas. Rates of TB in England outside London varied from 5.7 per 100,000 in South-West England to 18.7 per 100,000 in the West Midlands. Incidence rates per 100,000 population were 8.7 in Scotland, 5.8 in Wales and 3.3 in Northern Ireland. The majority of cases (72%) were in the population born outside the UK and in those aged 16–44 years (61%). The TB rate was higher in those born abroad than among those born in the UK (86 compared with 4.4 per 100,000). This reflected higher rates of TB in people from high-incidence countries, mainly South Asia. The risk of TB is highest in the 5 years after arrival in the UK. TB can also occur as a travel-related disease in UK residents from high-incidence countries, who return to visit their country of birth and are exposed to TB. The numbers of cases by region in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, in 2008, is shown in Table 40.2.

Table 40.2 Tuberculosis case reports and rates by UK region/country 2008 (adapted from Health Protection Agency, 2009)

| UK region/country | Number of cases | Rate per 100,000 population |

|---|---|---|

| London | 3376 | 44.3 |

| West Midlands | 1012 | 18.7 |

| North West | 745 | 10.8 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 647 | 12.4 |

| East Midlands | 517 | 11.7 |

| South East | 719 | 8.6 |

| East of England | 478 | 8.3 |

| South West | 297 | 5.7 |

| North East | 179 | 7.0 |

| England | 7970 | 15.5 |

| Scotland | 452 | 8.7 |

| Wales | 174 | 5.8 |

| Northern Ireland | 59 | 3.3 |

Diagnosis

Investigations

Chest radiography

The chest radiograph is a non-specific diagnostic tool, as TB may present as virtually any abnormality on chest radiography. This is why microbiological evidence of confirmation should be sought. Pulmonary TB may appear as bronchopneumonia with confluent shadowing, without cavitation. Cavitation may be seen, the incidence can vary between 10% and 30%. Uncharacteristic radiological patterns may occur in the presence of HIV infection (Davies, 2003).

Treatment

In treating TB, a number of factors are important:

Drug treatment

Treatment

The recommended standard treatment regimen for respiratory and most other forms of TB in the UK is:

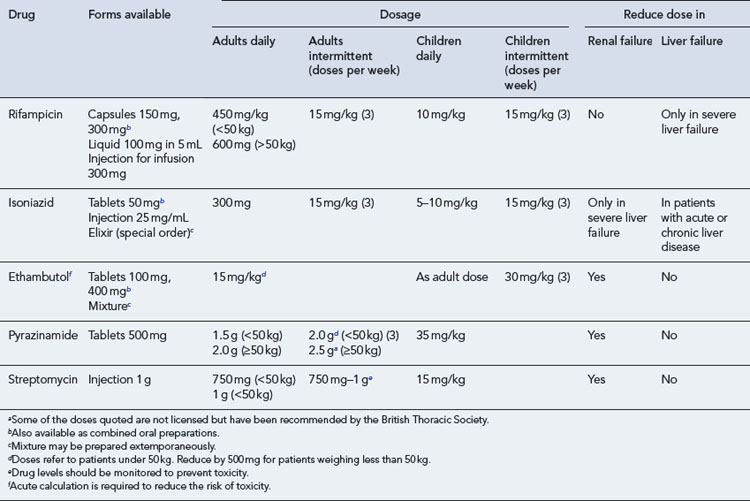

Patients should be started on the standard treatment regimen on clinical diagnosis and the doses of the first-line anti-tuberculous agents are shown in Table 40.3. The drugs used can be changed if drug-susceptibility testing shows evidence of resistance.

Meningeal TB

The use of glucocorticoids is also recommended in the management of meningeal TB and is commenced at the same time as anti-tuberculous drugs. Consideration should be given to their gradual withdrawal within 2–3 weeks of initiation. The recommended doses (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006) are:

The more recent British Infection Society (BIS) guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of TB of the central nervous system (CNS) in adults and children (Thwaites et al., 2009) recommend all patients with meningeal TB should receive adjunctive corticosteroids (dexamethasone) regardless of disease severity at presentation.

Pericardial TB

Although TB of the pericardium is rare in the UK, it is potentially important because of the possibility of cardiac tamponade and constrictive pericarditis, which are associated with a significant morbidity and mortality. The standard 6-month treatment regimen is recommended for patients with active pericardial disease. Glucocorticoids should also be prescribed at the following doses (National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence, 2006):

Treatment of TB in special circumstances

TB in children

The doses of drugs used in children are shown in Table 40.3. Doses are generally estimated to facilitate prescription of easily administered volumes of liquid or tablets of appropriate strength. Ethambutol should not routinely be used in young children, who would be unable to report visual disturbances should they occur. However, it may be used if there is toxicity or resistance to other agents.

TB and HIV co-infection

Guidelines for the treatment of TB/HIV co-infection (Pozniak et al., 2009) recommend that co-infected patients are managed by a multidisciplinary team which includes physicians with expertise in the treatment of both TB and HIV.

Drug-resistant TB

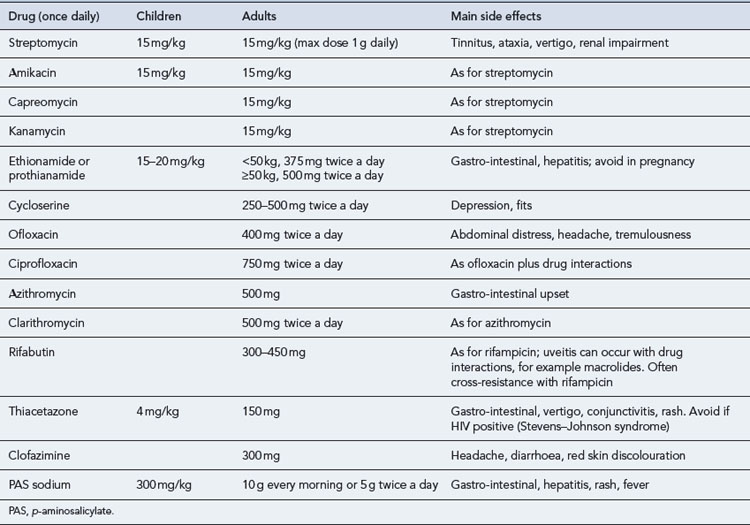

Drug-resistant TB is a considerable problem worldwide. In the UK, however, the proportion of TB isolates showing resistance is low (in 2008, 6% were resistant to isoniazid, 1.5% resistant to rifampicin, and 6.8% resistant to any first-line drug). Drug resistance is an important issue in the management of TB as it may compromise the effectiveness of treatment and prolong the period during which patients are infectious to others. Isoniazid is the most usual agent to which resistance is seen. Multi-drug resistance is important because the main bactericidal drugs, isoniazid and rifampicin, are ineffective. Treatment has to be individualised, requires a complex regimen involving the use of multiple reserve drugs and can cost at least £50,000 to £70,000 each to treat (Table 40.4). It is recommended that treatment of these individuals is only carried out by physicians with experience in drug-resistant TB; in hospitals, when inpatient treatment is necessary, with appropriate isolation facilities (negative pressure rooms); and in close conjunction with specialist centres.

Adverse reactions

The major adverse reactions of the first-line drugs are shown in Table 40.5. Rifampicin, isoniazid and pyrazinamide are all potentially hepatotoxic, and liver function should be checked before treatment commences with these drugs. Transient increases in transaminases and bilirubin commonly occur at the start of treatment although there is no need to continue to monitor liver function in patients where pre-treatment liver function was normal. However, liver function tests must be measured if fever, malaise, vomiting or jaundice develop and all drugs should be stopped. Liver function should be allowed to return to normal, at which time treatment can be recommenced one drug at a time. Clinical hepatitis is rare although patients may complain of vague symptoms such as abdominal pain and malaise which may indicate impending hepatitis.

Table 40.5 Major adverse reactions of first-line anti-tuberculous drugs

| Drug | Common reaction | Uncommon reaction |

|---|---|---|

| Isoniazid | Hepatitis, cutaneous hypersensitivity, peripheral neuropathy | |

| Rifampicin | Hepatitis, cutaneous reactions, gastro-intestinal reactions, thrombocytopaenic purpura, febrile reactions, ‘flu syndrome’ | |

| Pyrazinamide | Anorexia, nausea, flushing | Hepatitis, vomiting, arthralgia, hyperuricaemia, cutaneous hypersensitivity |

| Ethambutol | Retrobulbar neuritis, arthralgia |

In children older than 5 years of age, a dose of ethambutol of 15 mg/kg has been shown to be safe (Trebucq, 1997). A baseline ophthalmological assessment is important in children as in adults and should be repeated after 1–2 months.

Chemoprophylaxis

The use of chemoprophylaxis is important in preventing vulnerable individuals with LTBI from developing active TB disease. Without chemoprophylaxis, 40–50% of infants and 15% of older children with LTBI will develop active TB disease in 1–2 years. Prophylaxis is usually with isoniazid alone for 6 months or rifampicin and isoniazid for 3 months. Detailed guidance as to when isoniazid or rifampicin and isoniazid should be used has been produced by National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2006).

BCG vaccine

BCG vaccine contains a live, attenuated strain derived from M. bovis. It does not protect against infection, but it prevents the more serious forms of disease such as miliary TB and meningeal TB. The BCG immunisation programme in the UK is now a risk-based programme, the key part being a neonatal programme targeted at protecting those children most at risk of exposure to TB, particularly from the more serious forms of the disease (Department of Health, 2006). Most age groups require a Mantoux test prior to being offered BCG vaccine.

Patient care

Information for patients

A number of patients from abroad have a poor command of English. TB Alert has produced leaflets on the treatment of TB for patients. These can be found at the TB Alert website (http://www.tbalert.org/), and are available in languages other than English.

Directly observed therapy (DOT)

DOT regimens may be fully or partially intermittent. In the latter, four drugs (isoniazid, rifampicin, pyrazinamide and either ethambutol or streptomycin) are given daily for 2 months followed by rifampicin and isoniazid two or three times weekly for the subsequent 4 months. For most drugs, the doses are increased when given intermittently and these are shown in Table 40.3. Trials of intermittent regimens have shown treatment is as effective when given intermittently as when given daily.

Counselling points

Answers

Answers

Questions

Answers

Answers

British Thoracic Society. Control and prevention of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom. Thorax. 2000;55:887-901.

British Thoracic Society Joint Tuberculosis Committee. Chemotherapy and management of tuberculosis in the United Kingdom: recommendations. Thorax. 1998;53:536-548. With permission from BMJ Publishing Group Ltd

Davies P.D.O., editor. Clinical Tuberculosis. London: Arnold, 2003.

Department of Health. Immunisation Against Infectious Disease, Chapter 32, Tuberculosis: BCG Immunisation. London: DH. 2006. Available at http://www.dh.gov.uk/en/Publicationsandstatistics/Publications/PublicationsPolicyAndGuidance/DH_113027

Hawker J., Begg N., Blair I., et al, editors. Communicable Disease Control Handbook. Oxford: Blackwell, 2005.

Health Protection Agency. Tuberculosis in the UK: Annual Report on Tuberculosis Surveillance in the UK 2009. London: Health Protection Agency Centre for Infections; 2009.

Heymann D.L., editor. Control of Communicable Diseases Manual. Washington, DC: American Public Health Association, 2004.

National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence. Tuberculosis – Clinical Diagnosis and Management of Tuberculosis and Measures for Its Prevention and Control, CG 33.. London: NICE. 2006. Available at: http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG33

Pozniak A.L., Collins S., Coyne K.M., on behalf of the BHIVA Guidelines Writing Committee. Guidelines for the Treatment of TB/HIV Co-infection. London: British HIV Association; 2009. Available at: http://bhiva.org/documents/Guidelines/Treatment%20Guidelines/Current/TreatmentGuidelines2009.pdf

Thwaites G., Fisher M., Hemingway C., et al. The British Infection Society guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of tuberculosis of the central nervous system in adults and children. J. Infect.. 2009;59:167-187.

Trebucq A. Should ethambutol be recommended for routine treatment of tuberculosis in children? A review of the literature. Int. J. Tuberc. Lung Dis.. 1997;1:12-15.

WHO. Multidrug and Extensively Drug-Resistant TB (M/XDR-TB): 2010 Global Report on Surveillance and Response. Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241599191_eng.pdf

World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control. A Short Update to the 2009 Report. Geneva: WHO; 2009. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/ 2009/9789241598866_eng.pdf

American Thoracic Society, CDC, and Infectious Diseases Society of America. Treatment of Tuberculosis. MMWR; 2003. l52: RR-11

Campbell I.A., Bah-Sow O. Pulmonary tuberculosis: diagnosis and treatment. Br. Med. J.. 2006;332:1194-1197.

Health Protection Scotland. Tuberculosis: Clinical Diagnosis and Management of Tuberculosis and Measures for Its Prevention and Control in Scotland. Glasgow: Health Protection Scotland; 2009.

Schlossberg D., editor. Tuberculosis and Nontuberculous Mycobacterial Infections. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2006.

World Health Organization. Treatment of Tuberculosis Guidelines. Geneva: WHO; 2010. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2010/9789241547833_eng.pdf