CHAPTER 24 Tubal disease

Introduction

Ovum and embryo transport is probably the result of an interaction between the egg/embryo and the muscle contractions, ciliary activity and flow of tubal secretions. The relative importance of these factors is debatable, although there is evidence that ciliary activity plays a dominant role in gamete and embryo transport (Lyons et al 2006). Both myosalpingeal and ciliary activity are affected by a diverse range of chemical, biological and hormonal agents, including ovarian steroids, sympathomimetic agents, prostaglandins and angiotensin II (Jansen 1984, Saridogan et al 1996, Mahmood et al 1998).

Fallopian tubes probably act as sperm reservoirs, and this role may be essential for maintaining a certain number of sperm at the site of fertilization and preventing polyspermy by reducing the number of sperm available for fertilization. Sperm interaction with the tubal epithelium and secretions may also play an important role in the preparation of sperm for fertilization (Saridogan and Djahanbakhch 2009).

Tubal secretions contain proteins that derive from the plasma and also some specific substances synthesized within the oviduct itself (Maguiness et al 1992a). Both tubal proteins and the physical contact between the gametes and the tubal epithelium may play a role in gamete function (i.e. capacitation), fertilization and early embryo development (Djahanbakhch et al 1994, Kervancioglu et al 2000).

Aetiology of Tubal Disease

Salpingitis

Most salpingitis is the result of an ascending infection from the lower genital tract, caused primarily by Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae (see Chapter 61, Pelvic inflammatory disease, and Chapter 62, Sexually transmitted infections, for more information). These micro-organisms cause mucopurulent endocervicitis, and break down major cervical barriers, such as the mucus plug that protects the endometrium and upper genital tract, and permits ascending infection. Other pathogens such as Streptococcus sp., Escherichia coli and anaerobes ascend through the breached barrier and reach the upper genital tract (Rice and Schachter 1991). In a significant proportion of cases, no aetiological agent is identified; this suggests that a range of other aetiological agents have a role, but the identification of novel organisms is difficult to ascertain because of the limited availability of diagnostic tests. Serological evidence has associated Mycoplasma genitalium with pelvic inflammatory disease (Simms and Stephenson 2009).

In the majority of patients, salpingitis is due to a sexually transmitted infection. In other cases, iatrogenic manoeuvres such as insertion of an intrauterine device, termination of pregnancy, hysterosalpingography or curettage can spread a cervical infection into the uterus and tubes. In a small proportion of women, pelvic infection may be secondary to gastrointestinal infections such as perforated appendicitis. Mycobacterium tuberculosis is still seen in developing countries; however, migration to developed countries has resulted in a significant increase in the number of tuberculosis notifications since the 1980s (Rose et al 2001).

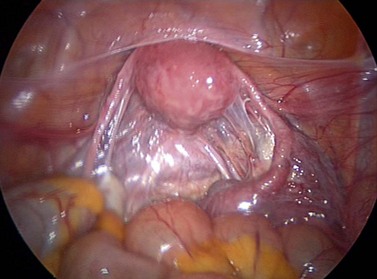

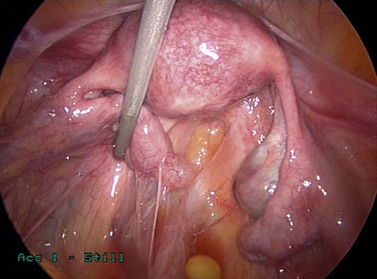

Acute salpingitis causes loss of ciliated cells and distal occlusion of the fallopian tubes. Some of the deciliation may be recovered later, but subsequent immune response following the acute phase causes permanent scarring, loss of mucosal folds and flattening of the mucosa (Lyons et al 2006). Distal occlusion of the tubes together with chronic inflammatory process could result in fluid collection in the lumen of the fallopian tube, leading to hydrosalpinges. Pelvic peritonitis during the acute phase may be followed by adhesions around the fallopian tubes and ovaries, distorting the pelvic anatomy. Perihepatic inflammation may cause ‘violin-string’ adhesions known as ‘Fitz–Hugh–Curtis syndrome’ (Figures 24.1–24.3).

Other causes

Endometriosis, fibroids, previous pelvic/tubal surgery, salpingitis isthmica nodosa, endosalpingiosis and cornual polyps can be the cause of cornual obstruction or tubal damage. Endometriosis is reviewed in Chapter 33. In some patients, tubal damage is secondary to previous tubal or pelvic surgery such as salpingotomy for ectopic pregnancy, ovarian cystectomy, myomectomy, ovarian wedge resection and shortening of round ligaments. Salpingitis isthmica nodosa was described by Chiari (1887) as nodular thickening of the proximal part of the fallopian tube. The aetiology of this entity is unknown but it is probably due to a non-inflammatory process.

Diagnosis

Assessment of the fallopian tube should normally determine patency, a normal external and internal appearance, the ability to transport gametes and the embryo, and provision of an environment for the early steps of reproduction to occur. It is possible that, apart from the obvious need for tubal patency to allow passage of gametes, factors that affect the gametes and embryo, the effectors of tubal transport, the cilia, flow of tubal fluid and tubal contractions appear to constitute a higher-order system in which intact function of each may not be needed to achieve pregnancy (Verdugo 1986). However, dysfunction of this higher-order system may be the reason for unsuccessful tubal surgery even when tubal patency has been achieved. Similarly, a functional disorder of this system may account for subfertility in some cases of unexplained infertility. Currently, tubal function is determined by demonstrating patency and normal appearance at laparoscopy.

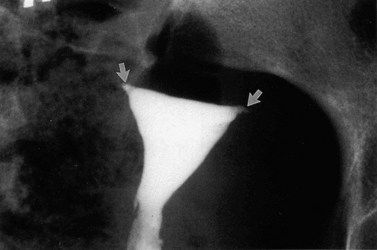

The methods commonly used to determine tubal patency are hysterosalpingography (HSG), laparoscopy and hysterosalpingo contrast sonography (HyCoSy). The first two methods have been used for many years, whereas HyCoSy is a relatively new technique. All these methods have some degree of false-negative and false-positive results in determining tubal patency. A comparison of HSG and laparoscopy showed that complete agreement of tubal patency was found in 80.2% of cases (Maguiness et al 1992b). Laparoscopy has the ability to identify peritubal adhesions, endometriosis, polycystic ovaries, and other pelvic and intra-abdominal pathology. However, it is usually performed under general anaesthesia and does not give information about the uterine cavity. In general, these methods are considered complementary investigations, offering very important information (Figures 24.4–24.6). Laparoscopy also allows the surgeon to operate on abnormalities detected such as pelvic adhesions and endometriosis, provided that they have the relevant experience and the patient’s consent has been obtained preoperatively.

The internal appearance of the fallopian tubes can be assessed by salpingoscopy. Salpingoscopy is the transabdominal examination of the tubal lumen by introducing an endoscope through the fimbrial end. Rigid endoscopes with a diameter of 2.8 mm allow excellent visualization of the infundibulum and ampulla as far as the ampullary–isthmic junction. The presence of minor intratubal lesions is not necessarily incompatible with fertility (Maguiness and Djahanbakhch 1992); however, loss of mucosal folds and intratubal fibrosis are significant. Nowadays, salpingoscopic assessment of the tubal lumen is recommended by some groups before tubal surgery for hydrosalpinges (Puttemans et al 1998). De Bruyne et al (1989) proposed a classification of ampullary findings in hydrosalpinges: grades 1 and 2 refer to normal salpingoscopic findings, grade 3 (intermediate group) refers to focal adhesions, and grades 4 and 5 refer to severe adhesions and loss of mucosal folds.

Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy and fertiloscopy approaches utilize the advantages of laparoscopy but with a less invasive approach (Gordts et al 1998, Watrelot et al 1999). Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy is the endoscopic examination of pelvic structures through the posterior vaginal fornix after instilling saline into the pouch of Douglas. This allows tubal patency to be checked, in addition to assessment of the pelvis for other pathology. Fertiloscopy includes salpingoscopy, microsalpingoscopy and hysteroscopy for complete examination of the female reproductive tract. These procedures can be performed under local anaesthesia or sedation.

Selective transcervical salpingography and tubal catheterization can be done in cases where it is doubtful that there is cornual obstruction (Ataya and Thomas 1991). Mucus plugs and debris can be mobilized, and a tube that was apparently obstructed can be ‘opened’ following such a procedure.

Treatment

The treatment of tubal disease in the infertile patient includes selective salpingography with tubal cannulation, surgery and in-vitro fertilization-embryo transfer (IVF-ET). In comparison with the other two options, IVF is now widely used for the majority of patients with tubal disease. However, it is relatively expensive, labour intensive and carries risks of multiple pregnancy and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (see Chapter 22, Assisted reproduction treatments, for more information).

Selective transcervical salpingography

Selective transcervical salpingography and tubal catheterization can be used for the treatment of proximal tubal obstruction in selected cases. A review of the literature on fluoroscopic tubal cannulation showed pregnancy rates of 22.7% and ectopic pregnancy rates of 3.2% (Honore et al 1999).

Reconstructive tubal surgery

With the advent of IVF-ET, the role of reconstructive tubal surgery has diminished. However, this type of surgery is still appropriate and effective for properly selected individuals (National Institute for Clinical Excellence 2004). Initial methods for tubal surgery were based on microsurgical techniques. The use of magnification and microsurgical techniques has been the traditional method. However, with advances in laparoscopic surgery, most of these methods are now possible to perform at laparoscopy.

Microsurgical treatment

The microscope was first used for tubal surgery by Walz (1959). Whilst others used delicate electrosurgery and magnification (loupes) in the treatment of hydrosalpinges, Paterson and Wood (1974) in Australia and Winston and McClure-Browne (1974) in England adapted their experience from animal experiments to humans and operated on infertile women, under high magnification, using an operating microscope.

Coadjuvants

The use of coadjuvants can sometimes help to avoid adhesion formation, but it is important to keep in mind that no coadjuvant will replace good surgical technique. Recent reviews of methods for preventing adhesions suggest that none of the methods have been clearly shown to improve pregnancy rates; however, some methods such as steroids, oxidized regenerated cellulose (Interceed) and polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex) reduce adhesion formation (Metwally et al 2006, Ahmad et al 2008).

Cornual occlusion

Cornual occlusion due to inflammatory causes was treated by uterotubal implantation with very poor results. Ehrler (1963) described his technique and suggested that the intramural portion of the tube could be spared in most patients. Microsurgical methods described by Winston (1977) and Gomel (1977) became the surgical technique of choice. Cornual implantation is now rarely used. Tubocornual implantation is avoided whenever possible. Destroying a possible sphincter at the uterotubal junction is associated with excessive bleeding and damage to the tubal blood supply; it shortens the tube and may increase the risk of rupture of the uterus in the event of subsequent pregnancy, which means that patients must be delivered by caesarean section.

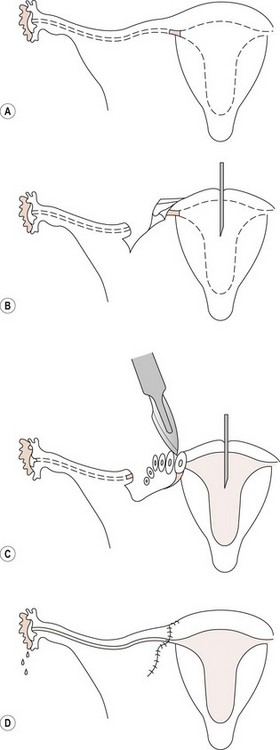

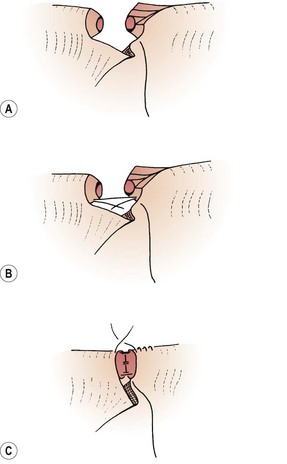

The use of magnification allows better identification of the intramural portion of the tube by careful shaving of the cornua until healthy tissue is found, permitting a more accurate tissue apposition with a watertight anastomosis between healthy tubal tissues. Once the ends are well defined, the anastomosis is done in two layers, using 8/0 nylon as a suture. The suture material should not penetrate the mucosa, only the muscularis (Seki et al 1977). In some cases, the use of a temporary splint gives considerable help, especially in deep cornual tubal anastomosis (Figure 24.7), but this should be removed at the end of the surgical procedure; if left in situ, the splint should not remain for more than 48 h as longer periods of time cause mucosal damage. Tension between the anastomosed ends must be avoided. A stitch of 6/0 Prolene between both ends of the mesosalpinx should be applied as a stay suture. More details about the technique have been given elsewhere (Winston 1977, Margara 1982).

Cornual polyps

Removal of cornual polyps is still a matter of controversy. Glazener et al (1987) stated that the removal of cornual polyps does not improve fertility and they are not a cause of infertility. However, consideration should be given to removal of large polyps present in the intramural or isthmic portion of the tube. This can involve salpingotomy and resection of the polyp without tubal resection or the opening of the cornu, and removal of the affected portion of the tube followed by cornual–isthmic anastomosis in two layers. In some cases when a large polyp is implanted deep in the intramural portion of the tube, the anastomosis can be difficult due to disparity of the lumen of the tubal ends. The portion where the polyp was present is wider than the isthmic portion of the tube, and it is not always easy to achieve a watertight anastomosis. For this reason, some surgeons prefer salpingotomy whenever possible.

Tubal anastomosis

Tubal anastomosis for reversal of sterilization is the most successful technique in microsurgery for the following reasons: healthy tissues are anastomosed, the localized damage is removed completely (Figure 24.8) and these patients are generally fertile.

Success depends on the length of the remaining tube. The minimum length of tube necessary to maintain fertility in women is not known. In animal experiments, fertility diminished in a linear fashion depending on the length of the ampulla resected; when more than 70% was missing, none of the animals became pregnant. Resection of the ampullary–isthmic junction did not appear to alter fertility (Winston et al 1977). The rabbit is far from an ideal model for human tubal physiology, but these results emphasize the fact that the ampulla seems to be important in maintaining fertility.

The length of time between sterilization and reversal is important and has a prognostic value. Vasquez et al (1980) demonstrated that after 5 years of sterilization, the proximal portion of the tube had a severely damaged mucosa with flattening of the epithelium and polyp formation. The surgical technique of reversal of sterilization has been described by Winston (1977) and Margara (1982).

Hydrosalpinges

As well as being a cause of infertility, hydrosalpinges also have a detrimental effect on the outcome of IVF-ET treatment, with reduced pregnancy and implantation rates and increased miscarriage rates. The hydrosalpinx fluid is known to be embryotoxic and may also reduce endometrial receptivity. Removal of hydrosalpinges prior to IVF-ET seems to lead to better results (Nackley and Muasher 1998, Zeyneloglu et al 1998). However, some groups believe that salpingectomy should only be performed when there is severe tubal pathology, and other patients should be given the chance of tubal surgery (Puttemans and Brosens 1996). A Cochrane review concluded that further randomized trials are required to assess other surgical treatments for hydrosalpinx, such as salpingostomy, tubal occlusion or needle drainage of a hydrosalpinx at oocyte retrieval (Johnson et al 2004).

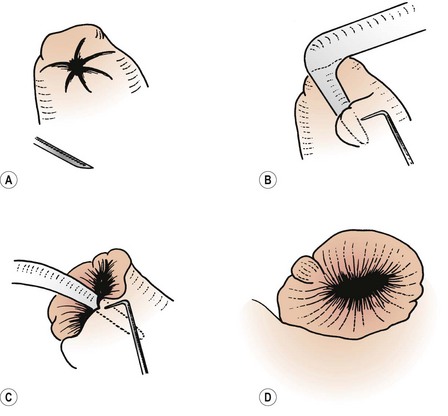

While dividing adhesions, special care must be taken to avoid damage to the fimbrial blood supply. These vessels are in the area of the connecting ligament between the ovary and the tube at the outer margin of the mesosalpinx. The hydrosalpinx must be opened at the most terminal part: the ‘pucker point’. This is where the fimbrial end has closed; it is clearly seen under the microscope as a thin fibrous line, often with an H-shaped configuration, and is not always the thinnest part of the tube. Linear salpingostomy has a high chance of healing over. Using fine diathermy, the tube is opened and a glass probe is introduced, following the fibrous tracts parallel to the blood vessels and ensuring that the mucosal folds are not cut. Using small incisions, the new tubal ostium is completed and then the mucosa can be everted (Figure 24.9).

Adhesions

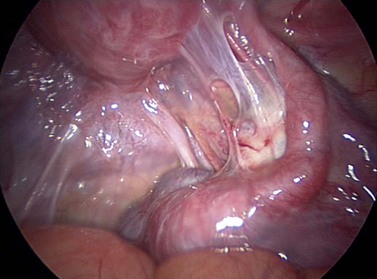

Ovarian adhesions should be removed from the ovarian capsule using diathermy or scissors, leaving the ovarian capsule as free as possible. Ovulation and egg release seem to improve after careful ovariolysis and may depend on the amount of the ovarian surface left free (Figure 24.10).

Figure 24.10 Laparoscopic appearance in a patient with severe periovarian adhesions after pelvic inflammatory disease.

Special attention must be paid to raw areas. The uterine surface and the surrounding peritoneum must be inspected carefully. Peritonealization is very important and all raw areas must be covered. If the ovarian fossa has been damaged in order to free or liberate a firmly adherent ovary, the raw area should be closed using a linear suture of 4/0 Prolene. If the raw area cannot be peritonealized using the surrounding peritoneum, a peritoneal graft can be applied. The peritoneum should be thin and without fatty tissue. It is attached to the raw area using 8/0 nylon or 6/0 Prolene. The donor areas can be the peritoneal layer of the anterior abdominal wall, the peritoneal space between the round ligament and the bladder and, in some cases, the peritoneum of the mesentery of the small or large bowel. This technique has proved very effective in experimental animals, and the results with humans are very encouraging. Synthetic materials are available to replace peritoneum (Hunter et al 1988, Haney and Dotty 1992). They can be applied during open surgery as well as laparoscopic procedures, and can remain in situ, apparently without side-effects; if removal is necessary, this can be done through a laparoscope.

Laparoscopic surgery

The development of laser beams for medical use also had an impact in laparoscopic surgery. The use of video-laparoscopy has become a standard part of laparoscopic surgery. It is less tiring, and the assistant has a more active role during surgical procedures, thus it facilitates training and teaching. Different methods of dissection using laser diathermy (Donnez and Nisolle 1989) or cold cutting (Serour et al 1989) have been discussed. There is no evidence that one is better than the other.

One of the most important attributes of this method is that it probably has a low rate of adhesion formation. There is no doubt that laparoscopic adhesiolysis is very effective for pain, and open surgery may cause more adhesion formation (Lundford et al 1991). The question still remains whether patients with severe tubal damage, not suitable for open procedures, should be operated upon using the laparoscopic approach when the prognosis is very poor and alternative methods are available to them.

Results

Proximal tubal disease

Selective salpingography and tubal catheterization can achieve high patency rates and pregnancy rates of 49% (Honore et al 1999). With the exception of reversal of sterilization, laparoscopic surgery has a limited place in the treatment of proximal tubal disease. Microsurgical cornual anastomosis offers very good results in selected groups of patients. Postoperative laparoscopies show a high patency rate amongst those patients who have not conceived. The major limiting factors seem to be the recrudescence of the disease or extension of the original inflammation into the anastomotic site, rather than lack of patency. Gomel (1980) reported that 53% of patients conceived and had at least one term pregnancy.

Following tubocornual anastomosis by microsurgery, the reported term pregnancy rates in the literature vary between 22% and 57%, and ectopic pregnancy rates vary between 2% and 12%. These results are similar to cumulative delivery rates following five cycles of IVF-ET (Posaci et al 1999). In contrast, the outcome of tubouterine anastomosis is much poorer, and this procedure has mostly been replaced by tubocornual anastomosis.

Reversal of sterilization

Reversal of tubal sterilization is the most successful procedure in tubal surgery. Both open microsurgical and laparoscopic reversals offer high pregnancy rates. The pregnancy rates in the literature following reversal of sterilization with microsurgery vary between 33% and 86%, with ectopic pregnancy rates of 1–14%. Pregnancy rates of up to 87.1% have been reported following laparoscopic reversal of sterilization (Yoon et al 1999). The success rates are lower after sterilization with cautery or Pomeroy’s technique compared with clip or ring sterilization (Posaci et al 1999).

Salpingostomy

Boer-Meisel et al (1986), in a prospective study, classified hydrosalpinges as grades I, II and III, based on the nature and extent of the adhesions, the microscopic aspect of the endosalpinx, the thickness of the tubal wall and the diameter of the hydrosalpinx. In their series, 77% of patients with grade I hydrosalpinx had the possibility of conception, compared with 21% with grade II and only 3% with grade III. Thus, surgery is the obvious treatment for patients with grade I hydrosalpinges. Patients with grade III hydrosalpinges should avoid salpingostomy and should be treated using IVF techniques after salpingectomy. The difficult group is that of grade II hydrosalpinx, where treatments with IVF or tubal surgery have the same prognosis. Age, social and religious background, the possibility of alternative treatment and the patient’s wishes must be considered very carefully.

The success of tubal microsurgery for distal tubal lesions depends on several factors. Patients with extensive pelvic adhesions, a thick tubal wall and abnormal tubal mucosa at salpingoscopy have poor results. Type of surgery also affects the outcome. Pregnancy rates as high as 59–60% can be achieved with fimbrioplasty, but the results after salpingostomy may not be as good (Posaci et al 1999). Patients with poor prognostic factors will have a higher chance of achieving pregnancy with IVF, whereas in the absence of poor prognostic factors, tubal microsurgery should be the first choice.

Laparoscopic surgery

Laparoscopic adhesiolysis for pelvic adhesions results in very good results, with term pregnancy rates of 47–62% and ectopic pregnancy rates of 4–8%. These results are similar to those achieved after microsurgery, so laparoscopic surgery should be the first option for suitable patients (Posaci et al 1999).

Success rates of laparoscopic surgery for distal tubal lesions also depend on several prognostic factors, including the presence of extensive pelvic adhesions, a thick tubal wall and severe endotubal damage. The reported intrauterine pregnancy rates following laparoscopic surgery for distal tubal lesions vary between 13% and 51%, with ectopic pregnancy rates of 3–23% (Posaci et al 1999). It appears that laparoscopic surgery offers similar success rates compared with microsurgery for lesser degrees of distal tubal damage. However, open microsurgery may be slightly better for more severe distal tubal disease. For the treatment of moderate to severe distal tubal disease, postoperative pregnancy rates are low, even after microsurgery, despite long periods of observation (>2 years), with remarkably high ectopic pregnancy rates. For this reason, IVF is preferable in these situations (Ozturk and Saridogan 2009).

Conclusion

KEY POINTS

Ahmad G, Duffy JMN, Farquhar C et al 2008 Barrier agents for adhesion prevention after gynaecological surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD000475.

Ataya K, Thomas M. New techniques for selective transcervical osteal salpingography and catheterisation in the diagnosis and treatment of proximal tubal obstruction. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;56:980-983.

Boer-Meisel ME, te Velde ER, Habbema JD, Kardaun JW. Predicting the pregnancy outcome in patients treated for hydrosalpinx: a prospective study. Fertility and Sterility. 1986;45:23-29.

Chiari H. Zur pathologischen Anatomic des Eileiter-Catrrhs. Zeitschrift fur Heilkunde. 1887;8:457-473.

De Bruyne F, Puttemans P, Boeckx W, Brosens IA. The clinical value of salpingoscopy in tubal infertility. Fertility and Sterility. 1989;51:339-340.

Djahanbakhch O, Kervancioglu E, Maguiness SD, Martin JE. Fallopian tube epithelial cell culture. In: Grudzinskas JG, Chapman MG, Chard T, Djahanbakhch O, editors. The Fallopian Tube. Clinical and Surgical Aspects. London: Springer-Verlag; 1994:37-51.

Donnez J, Nisolle M. CO2 laser laparoscopy surgery. Adhesiolysis, salpingostomy, laser uterine nerve ablation and tubal pregnancy. Baillière’s Clinics in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1989;3:525-543.

Ehrler P. Die intramurale tubenanastomoze (ein Beitrag zur Uberwindung der Tubaren Steritat). Zentralblatt für Gynaekologie. 1963;85:393-400.

Glazener CMA, Loveden LM, Richardson SJ, Jeans WD, Hull MGR. Tubocornual polyps: their relevance in subfertility. Human Reproduction. 1987;2:59-65.

Gomel V. Tubal reanastomosis by microsurgery. Fertility and Sterility. 1977;28:59.

Gomel V. Clinical results of infertility microsurgery. In: Crosignani PG, Rubin BL, editors. Microsurgery in Female Infertility. New York: Academic Press; 1980:77-94.

Gordts S, Campo R, Rombauts L, Brosens I. Transvaginal hydrolaparoscopy as an outpatient procedure for infertility investigation. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:99-103.

Haney AF, Dotty E. Murine peritoneal injury and de novo adhesion formation caused by oxidized-regenerated cellulose (Interceed TC7) but not expanded polytetrafluoroethylene (Gore-Tex surgical membrane). Fertility and Sterility. 1992;57:202-208.

Honore GM, Holden AE, Schenken RS. Pathophysiology and management of proximal tubal blockage. Fertility and Sterility. 1999;71:785-795.

Hunter SK, Scott JR, Hull D, Urry RL. The gamete and embryo compatibility of various synthetic polymers. Fertility and Sterility. 1988;50:110-116.

Jansen RP. Endocrine response in the fallopian tube. Endocrine Reviews. 1984;5:525-551.

Johnson N, van Voorst S, Sowter MC, Strandell A, Mol BWJ 2004 Surgical treatment for tubal disease in women due to undergo in vitro fertilisation. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 3: CD002125.

Kervancioglu ME, Saridogan E, Aitken RJ, Djahanbakhch O. Importance of sperm to epithelial cell contact for the capacitation of human spermatozoa in human Fallopian tube–epithelial cell coculture. Fertility and Sterility. 2000;74:780-784.

Lundford P, Hahlin M, Kallfelt B, Thourburn J, Lindblom B. Adhesion formation after laparoscopic surgery in tubal pregnancy: a randomised trial versus laparotomy. Fertility and Sterility. 1991;55:911-915.

Lyons R, Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O. The reproductive significance of human fallopian tube cilia. Human Reproduction Update. 2006;12:363-372.

Maguiness SD, Djahanbakhch O. Salpingoscopic findings in women undergoing sterilization. Human Reproduction. 1992;7:269-273.

Maguiness SD, Shrimanker K, Djahanbakhch O, Grudzinskas JG. Oviduct proteins. Contemporary Reviews in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 1992;4:42-50.

Maguiness SD, Djahanbakhch O, Grudzinskas JG. Assessment of the fallopian tube. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. 1992;47:587-603.

Mahmood T, Saridogan E, Smutna S, Habib AM, Djahanbakhch O. The effect of ovarian steroids on epithelial ciliary beat frequency in the human fallopian tube. Human Reproduction. 1998;13:2991-2994.

Margara RA. Tubal reanastomosis. In: Chamberlain G, Winston RML, editors. Tubal Infertility. Oxford: Blackwell Science; 1982:106-119.

Metwally ME, Watson A, Lilford R, Vanderkerchove P 2006 Fluid and pharmacological agents for adhesion prevention after gynaecological surgery. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2: CD001298.

Nackley AC, Muasher SJ. The significance of hydrosalpinx in in vitro fertilization. Fertility and Sterility. 1998;69:373-384.

National Institute for Clinical Excellence. Assessment and Treatment for People with Fertility Problems. Ref: CG011. London: NICE; 2004. Available at http://www.nice.org.uk

Ozturk O, Saridogan E. Laparoscopic surgery for tubal factor infertility. In: Allahbadia G, Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O, editors. The Fallopian Tube. Tunbridge Wells: Anshan; 2009:283-289.

Paterson P, Wood C. The use of microsurgery in the reanastomosis of the rabbit fallopian tube. Fertility and Sterility. 1974;25:757-761.

Posaci C, Camus M, Osmanagaoglu K, Devroey P. Tubal surgery in the era of assisted reproductive technology: clinical options. Human Reproduction. 1999;14(Suppl 1):120-136.

Puttemans PJ, de Bruyne F, Heylen SM. A decade of salpingoscopy. European Journal of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 1998;81:197-206.

Puttemans PJ, Brosens IA. Preventive salpingectomy of hydrosalpinx prior to IVF. Salpingectomy improves in-vitro fertilization outcome in patients with hydrosalpinx: blind victimization of the fallopian tube. Human Reproduction. 1996;11:2079-2084.

Rice PA, Schachter J. Pathogenesis of pelvic inflammatory disease. What are the questions? JAMA: the Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;266:2587-2593.

Rose AM, Watson JM, Graham C, et al. Tuberculosis at the end of the 20th century in England and Wales: results of a national survey in 1988. Thorax. 2001;56:173-179.

Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O, Puddefoot JR, et al. Angiotensin II receptors and angiotensin II stimulation of ciliary activity in human fallopian tube. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 1996;81:2719-2725.

Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O. Gamete and embryo transport in the human fallopian tube. In: Allahbadia G, Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O, editors. The Fallopian Tube. Tunbridge Wells: Anshan; 2009:12-19.

Seki K, Eddy CA, Smith Nk, Pauerstein CJ. Comparison of two techniques of suturing in microsurgical anastomosis of the rabbit oviduct. Fertility and Sterility. 1977;28:1215-1219.

Serour GI, Bandroui MH, Agizi HM, Hamed AF, Abdel-Aziz F. Laparoscopic adhesiolysis for infertile patients with pelvic adhesive disease. International Journal of Gynaecology and Obstetrics. 1989;30:249-252.

Simms I, Stephenson J. Epidemiology of pelvic inflammatory disease. In: Allahbadia G, Saridogan E, Djahanbakhch O, editors. The Fallopian Tube. Tunbridge Wells: Anshan; 2009:537-546.

Vasquez G, Winston RML, Boeckx W, Brosens I. Tubal lesions subsequent to sterilisation and their relation to fertility after attempts at reversal. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 1980;138:86-92.

Verdugo P. Functional anatomy of the fallopian tube. In: Insler V, Lunenfeld B, editors. Infertility: Male and Female. London: Churchill Livingstone; 1986:26-55.

Walz W. Fertilitäts Operationen mit Hilfe eines Operationemkroscopes. Geburtshilfe und Gynaekologie. 1959;153:49-53.

Watrelot A, Dreyfus JM, Andine JP. Evaluation of the performance of fertiloscopy in 160 consecutive infertile patients with no obvious pathology. Human Reproduction. 1999;14:707-711.

Winston RML. Microsurgical tubocornual anastomosis for reversal of sterilisation. Lancet. 1977;i:284-285.

Winston RML, McClure-Browne JC. Pregnancy following autograft transplantation of the fallopian tube and ovary in the rabbit. Lancet. 1974;i:494-497.

Winston RML, Frantzen C, Oberti C. Oviduct function following resection of the ampullary–isthmic junction. Fertility and Sterility. 1977;28:284-289.

Yoon TK, Sung HR, Kang HG, Cha SH, Lee CN, Cha KY. Laparoscopic tubal anastomosis: fertility outcome in 202 cases. Fertility and Sterility. 1999;72:1121-1126.

Zeyneloglu H, Arici A, Olive DL. Adverse effects of hydrosalpinx on pregnancy rates after in vitro fertilization-embryo transfer. Fertility and Sterility. 1998;70:492-499.