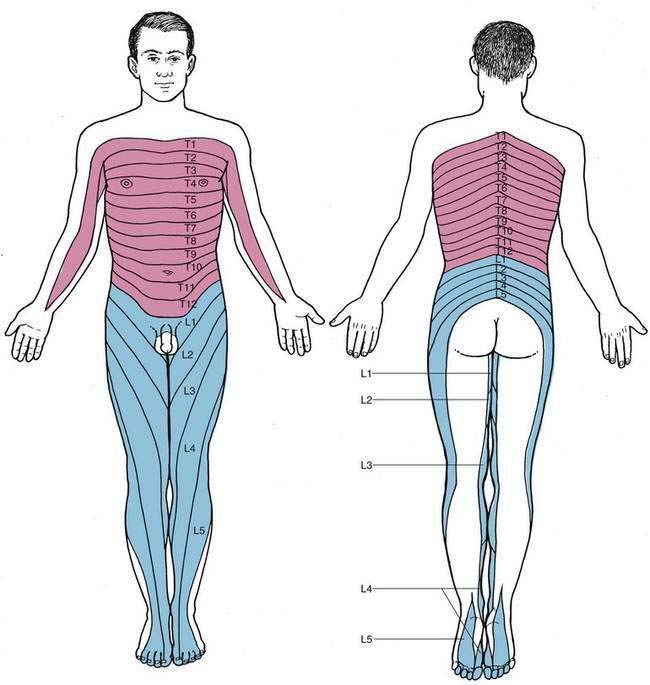

31 Truncal Block Anatomy

A number of regional anesthetic techniques rely on block of the thoracic or lumbar somatic (paravertebral) nerves. As illustrated in Figure 31-1, thoracic and lumbar somatic innervation extends from the chest and axilla to the toes. Although few major surgical procedures can be carried out under somatic block alone, appropriate use of somatic block with long-acting local anesthetics provides unique and useful analgesia. Also, when even longer-acting local anesthetics become available, possibly some form of thoracic or lumbar somatic nerve block, such as intercostal or paravertebral nerve block, will be able to provide even more useful postoperative analgesia. This is approaching clinical relevance with thoracic paravertebral use during care of patients undergoing breast surgery.

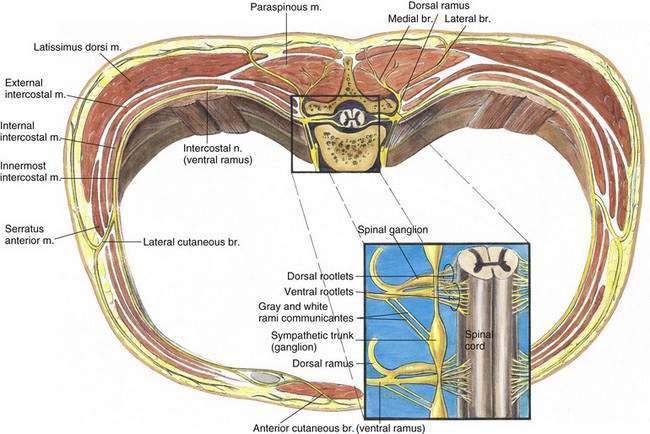

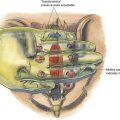

One of the advantages that somatic (paravertebral) block has over neuraxial blocks is the ability to avoid widespread interruption of the sympathetic nervous system. As shown in Figure 31-2, the major somatic nerves are the ventral rami of the thoracic and lumbar nerves. In addition, as shown in the inset in Figure 31-2, the nerves contribute preganglionic sympathetic fibers to the sympathetic chain through the white rami communicantes and receive postganglionic neurons from the sympathetic chain through gray rami communicantes. These rami from the sympathetic system connect to the spinal nerves near their exit from the intervertebral foramina. The dorsal rami of these spinal nerves provide innervation to dorsal midline structures. The medial branch of the dorsal primary ramus supplies the dorsal vertebral structures, including the supraspinous and intraspinous ligaments, the periosteum, and the fibrous capsule of the facet joint.