CHAPTER 144 Trigeminal Schwannomas

Epidemiology and History

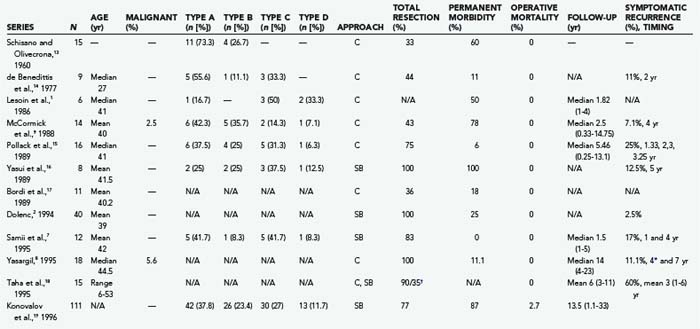

Trigeminal schwannomas (TSs) are benign, slow-growing tumors arising from the peripheral nerve sheath of the trigeminal nerve. Although the trigeminal nerve is the second most common intracranial site for schwannomas after the vestibular nerve, TSs are very rare tumors. Schwannomas make up roughly 8% of intracranial tumors, and TSs account for 0.8% to 8.0% of all intracranial schwannomas.1–7 This corresponds to 0.07% to 0.36% of all intracranial tumors. The peak incidence is observed in the fourth and fifth decades.1–5,7,8 TSs are slightly more common in females.9 Dixon in 1846 and Smith in 1849 were the first authors to describe primary tumors arising from the gasserian ganglion.10 Frazier reported the first successful removal of a TS in 1918,11 and the first clinical series was presented by Cuneo and Rand in 1927.12 Several hundred cases have been reported since.6,9 Earlier studies had reported low total resection rates and high mortality and morbidity. However, the introduction of microsurgery and skull base techniques has improved results considerably (Table 144-1).1–3,5–9,13–24 Today, TSs can be diagnosed reliably with noninvasive techniques, and total surgical resection with virtually no mortality and very low permanent morbidity can be accomplished in benign cases. In the past few decades, radiosurgery has also been established as a safe and effective adjuvant therapy for residual or recurrent tumors or as primary treatment in carefully selected cases.

Pathology and Pathogenesis

Schwannomas are encapsulated, benign tumors and are classified as World Health Organization grade I.25 In the literature they are also commonly referred as neuromas,3 neurinomas,26 and neurilemmomas.15 Schwannomas are distinct from traumatic neuromas, which are a non-neoplastic proliferation of Schwann cells in response to nerve trauma, and from neurofibromas, which are well-circumscribed intraneural or infiltrative extraneural tumors of the peripheral nerve sheath. Rare malignant schwannomas can also be seen and represent 0% to 7.9% of cases in large series.1–3,6,7,9,15,27–31 Schwannomas arise from the peripheral nerve sheath, distal to the oligodendroglia–Schwann cell junction. The trigeminal nerve and the gasserian ganglion are the most common sites for intracranial schwannomas after the vestibular nerve. Although most schwannomas are sporadic tumors, they may also be seen in association with neurofibromatosis type 225 or in patients with schwannomatosis.32 In such cases, TSs can occur along with schwannomas of other cranial nerves.

Pathologic Anatomy and Classification Schemes

The trigeminal nerve is associated with motor, sensory, and proprioceptive function. Sensory fibers innervate the scalp, face, mucous membranes of the nose, nasal cavity, and mouth. Motor fibers innervate the muscles of mastication: the tensor, digastric, and mylohyoid muscles. The nuclei in the brainstem extend from the inferior colliculi to the second segment of the cervical spinal cord. The trigeminal nerve root originates on the lateral aspect of the rostral pons; courses cranially, laterally, and anteriorly toward the petrous apex; and enters Meckel’s cave through the trigeminal pore, just inferior to the superior petrosal sinus.33 This first portion, which extends from the brainstem to Meckel’s cave, is called the cisternal segment. The nerve root is myelinated by oligodendrocytes from its origin at the brainstem up to the central myelin–peripheral myelin transition zone, where this function is taken over by Schwann cells. The trigeminal nerve root sheath has its central myelin–peripheral myelin transition zone at a mean of 1.13 mm on the medial and 2.47 mm on the lateral side away from the root entry zone at the brainstem.34 Schwannomas arise from the peripheral myelin zone. In the cisternal segment the trigeminal nerve root resides inside the cerebellopontine angle. After entering the trigeminal pore, it courses intradurally in the trigeminal cistern within two leaflets of the dura, which is called Meckel’s cave. It lies posterolateral to the sella and the cavernous sinus.

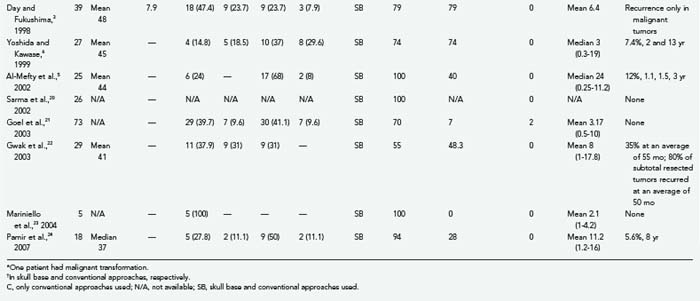

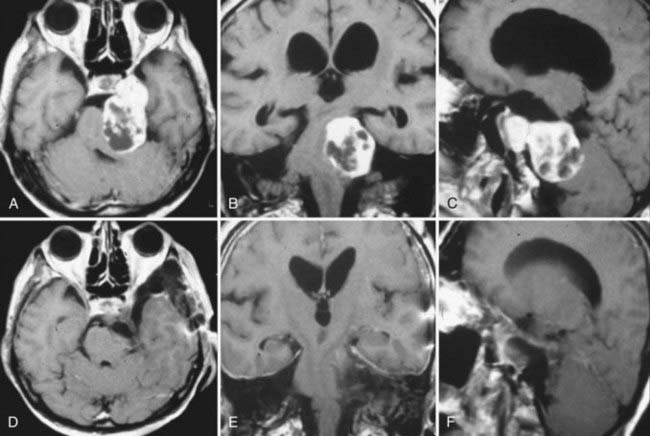

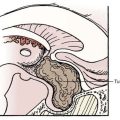

TSs may arise from the gasserian ganglion, the trigeminal nerve root, and the three divisions of the nerve. According to the point of origin, the tumor may be localized to the middle fossa (commonly referred as the “ganglion type”), the posterior fossa (commonly referred as the “root type”), or the extracranial space or may extend into several of these compartments (Fig. 144-1).3 Schwannomas arising from the gasserian ganglion grow into Meckel’s cave. Growth from the root of cranial nerve V (CN V) in the posterior fossa occurs subdurally in the cerebellopontine angle, whereas growth into the extracranial branches in the orbit and infratemporal fossa occurs epidurally. The tumor may extend into the orbit through the superior orbital fissure, to the infratemporal fossa through the foramen ovale or foramen rotundum, and to the cavernous sinus through the lateral wall and the cerebellopontine angle through the trigeminal pore.

The location of the tumor also directs the surgical approach. Therefore, several surgical classification schemes have been proposed to guide the surgical approach. Jefferson proposed a very useful scheme in 1953 and classified TSs into middle fossa (type A), posterior fossa (type B), and dumbbell (type C) tumors.30 This classification scheme has gained common acceptance in the neurosurgical community, and a slight modification was made by Day and Fukushima in their 1998 publication.3 Day and Fukushima described type D tumors, which arise from the extracranial portion of the trigeminal nerve.3 These tumors arise from either the maxillary or mandibular divisions and extend into the infratemporal fossa through the foramen ovale or rotundum, respectively.3 Dolenc,2 Samii and colleagues,7 Yoshida and Kawase,6 Al-Mefty and coworkers,5 Goel,4 and Gwak and associates22 have also proposed alternative classification schemes. The majority of TSs stay confined to a single cranial fossa (50% to 80%).9,13,15,16,24,35 The most common location is the middle cranial fossa (50%), followed by posterior fossa (30%) and dumbbell (20%) tumors.30,36 When 383 patients in 13 large series were analyzed together, type A schwannomas made up 36.6%; type B schwannomas, 18.3%; type C schwannomas, 34.5; and type D schwannomas, 10.7% of all cases (Table 144-1). The incidence of TSs that extend into the multiple cranial spaces is reported to range from 27% to 59%.24 Cavernous sinus involvement is frequent and seen in up to 38% of TSs.18,37 The tumor grows intradurally within Meckel’s cave and by expansion rather than invasion. The walls of Meckel’s cave are not rigid and can accommodate even a large tumor mass without disruption of the dural barrier. As expected, the majority of TSs do not invade the cavernous sinus proper or the internal carotid adventitia.18,37,38 The lateral wall of the cavernous sinus may be penetrated in rare cases with involvement of the vascular channels. This is also a frequent site of recurrence.18

Clinical Findings

Schwannomas may arise from any segment of the trigeminal nerve, from the root in the cisternal segment to the divisions exiting through cranial foramina. Symptoms may vary according to the point of origin and direction/extent of tumor growth. There are no specific findings diagnostic of TS. Trigeminal nerve–related complaints are the initial symptom in the vast majority of patients. Different studies have reported them in 90% to 100% of cases.1,3,9,15,31 Facial hypoesthesia is the most common trigeminal symptom and is present in 70% of patients.6 In most cases, all three divisions are affected. Facial pain or trigeminal motor dysfunction is less commonly encountered. The pain has a paroxysmal, lancinating character and is similar to trigeminal neuralgia. However, the absence of triggering mechanisms, its long duration, and unresponsiveness to drugs differ from classic trigeminal neuralgia.3 In 13% to 38.5% the pain syndrome may be identical to trigeminal neuralgia.3,9 In very rare cases of malignant invasion of the gasserian ganglion, complete anesthesia in all three divisions may be encountered.27,29,30 Other cranial nerve deficits are also seen, but trigeminal involvement is usually more severe. Diplopia is a common symptom and in most cases is related to abducens nerve compression by a middle fossa tumor. Abducens nerve palsy is detected in 26% of patients.6 Headaches, hemifacial spasm, and focal seizures may also be seen. Long-tract signs such as hemiparesis or gait disturbance may also occur. TSs in the cerebellopontine angle result in hearing loss, tinnitus, or gait disturbances (or any combination of these symptoms).15 Facial nerve involvement and long-tract and cerebellar signs may also be seen. Hearing loss and facial nerve dysfunction have been reported in patients with significant erosion of the petrous bone causing damage to the inner ear structures or creating conductive pathologies.15,30,31,39 Far less common symptoms include isolated sixth nerve palsy without trigeminal nerve involvement,40 which may be due to compression of CN VI in Dorello’s canal. The duration of symptoms may vary from a few months to several years.6 Sudden onset of headache secondary to intratumoral hemorrhage has been reported rarely.6,41,42

In the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) era, incidental TSs have also been detected.6 Decision making for incidental meningiomas is more complicated, and most do agree that as long as the patient is asymptomatic, close follow-up with MRI is the optimal choice, especially in elderly patients. However, previous studies have indicated that nonvestibular intracranial schwannomas have a higher incidence of growth than do sporadic vestibular schwannomas but less so than in patients with neurofibromatosis type 2.43 Therefore, early intervention is advisable in symptomatic cases.

Neuroradiologic Evaluation

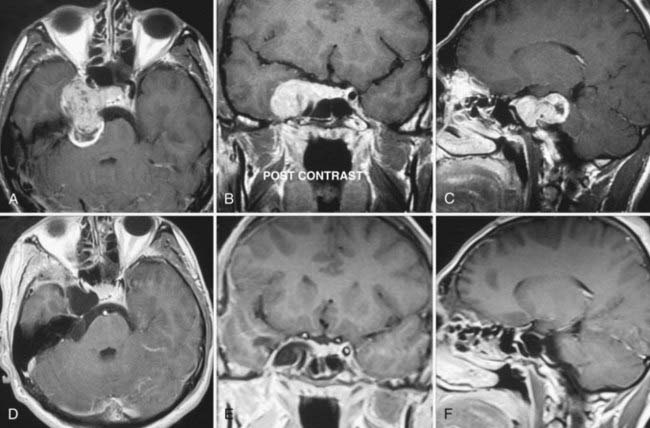

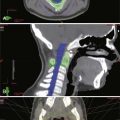

MRI and computed tomography (CT) are the “gold standards” for imaging of TSs, with MRI being the preferred mode. Schwannomas appear as well-circumscribed, heterogeneously enhancing masses that are isointense or hypointense on T1-weighted (T1W) images and, most commonly, hyperintense on T2-weighted (T2W) images.24,44–46 Cystic changes or rare intratumoral hemorrhage may be seen.24,47 Cystic changes were reported in 39% to 40% of the tumors.5,24 MRI also provides valuable information on cavernous sinus invasion. Magnetic resonance venography may be performed to demonstrate the vein of Labbé and other venous structures.5 On CT, schwannomas appear isointense to hyperintense in comparison to surrounding brain parenchyma. Most commonly they enhance intensely after injection of iodinated contrast material.45,48,49 Enhancement on CT studies was reported in 33% to 50% of the tumors.5,24 CT is the preferred method to demonstrate bone erosion. In our experience we have detected bone erosion in 70% of patients.24 High-resolution CT clearly demonstrates tumor location and extent and accompanying bony changes.

Plain films are of limited value in imaging TS. In advanced cases, erosion of the petrous apex may be seen, which is highly suggestive of TS.1,50 Yasargil, while reporting his surgical results on 18 predominantly large TSs, noted that petrous erosion was detected in 83.3% of his patients.8 Enlargement of the foramen ovale and spinosum may be found in tumors that invade these structures.

The differential diagnosis includes metastatic tumors, lymphomas, meningiomas, dermoid tumors, bone tumors (such as chondrosarcoma and chondromyxofibroma), chordomas, juvenile angiofibromas, cavernous hemangiomas, and thrombosed giant intracavernous or basillary aneurysms. Meningiomas appear as uniformly and intensely enhancing masses in the cerebellopontine angle cistern and attach with a broad base to the petrous bone. On T1W imaging they are isointense with respect to the brain and have a variable signal on T2W imaging. Meningiomas do not enlarge the internal acoustic meatus and have focal and dense calcifications. The presence of a brightly enhancing dural tail strongly supports the diagnosis of meningioma.51 Vestibular schwannomas, or schwannomas arising from the facial nerve, other oculomotor nerves, or the sympathetic plexus, can at times be difficult to differentiate from trigeminal schwannomas. Enlargement of the internal acoustic meatus supports the diagnosis of vestibular schwannoma. Calcifications, which are commonly present in meningiomas, are not seen in schwannomas. Metastatic lesions, lymphomas, chordomas, and chondrosarcomas appear to be invasive, in contrast to the well-circumscribed schwannomas. Epidermoid tumors grow across the tentorial incisura from the anterolateral aspect of the posterior fossa or occur primarily in the hippocampal portion of the choroidal fissure; appear as low-density lesions on CT, almost as low as cerebrospinal fluid (CSF); are hypointense on T1W images and hyperintense on T2W images; and have restricted diffusion. Cavernous hemangiomas of the cavernous sinus may also appear isointense to hypointense on T1W images. However, they enhance strongly with contrast material and appear markedly hyperdense on T2W images.

Surgical Treatment

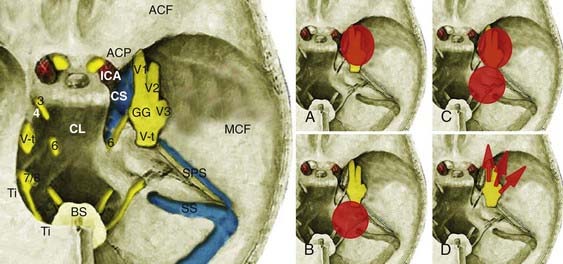

Type A TSs arise from the gasserian ganglion, grow in the interdural space in Meckel’s cave, and are localized to the middle cranial fossa (Fig. 144-2). They are enveloped by the inner membrane of the cavernous sinus, which is composed of the perineurium of cranial nerves within the cavernous sinus. Conventionally, middle fossa TSs have been resected via pterional trans-sylvian, subtemporal interdural, frontotemporal interdural, and frontotemporal extradural approaches.2,7,18,23 These approaches were based on initial extradural exposure of the gasserian ganglion followed by an interdural approach. Such an approach provides sufficient exposure for tumor resection but requires significant brain retraction to expose the tumor and sacrifice of bridging veins at the temporal tip. An alternative, extradural strategy was first described by Dolenc.2,52 Extradural skull base approaches provide more direct access to the tumor and have minimized the amount of brain retraction required. As originally described by Dolenc,2,52 Yasui and coworkers,16 and Yoshida and Kawase,6 these approaches are grouped as cavernous sinus explorations and are based on exposure of the dural sleeve around the ophthalmic or maxillary branches and stripping of the two layers of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus to expose Meckel’s cave. The Dolenc approach involves a frontotemporal craniotomy, unroofing of the orbit, exposure of the superior orbital fissure, and drilling of the anterior clinoid and anterior wall of the middle fossa (part of the greater sphenoid wing). An approach exposing the dural sleeve around the maxillary division can be performed with a frontal-orbital-zygomatic or simply a temporal craniotomy. Zygomatic osteotomies are used to obtain a more inferior view of the angle and decrease the need for brain retraction.6,52 Extradural approaches are advantageous in that they provide direct access to the tumor, require less brain retraction, and preserve the lobar drainage routes.

Type B TSs originate from the cisternal portion of the trigeminal nerve and are predominantly located within the cerebellopontine angle cistern. These tumors make up approximately a fifth of all cases of TS. TSs located solely in the posterior fossa do not pose any special surgical problems and can easily be resected via a conventional paramedian suboccipital approach with the same technique as used for vestibular schwannomas.13,36,53 In the event of extension into the middle fossa or the cavernous sinus, wider exposure can be achieved with a transpetrosal or combined petrosal approach.3,4,9,16 Subtemporal transtentorial approaches have also been advocated by others; however, interposition of the tumor between the surgeon and poorly visualized important neurovascular structures complicates its use.3

Type C TSs are the most challenging treatment group because these tumors have significant components in both the middle fossa and posterior fossa. Extension into multiple cranial fossae is not uncommon with TSs and is found in roughly a third of cases. Surgically, a subtemporal transtentorial route was advocated by Bordi and colleagues17 and McCormick and associates9; however, it has important drawbacks as indicated earlier. Cranial-orbital-zygomatic, petrosal, and combined petrosal approaches have been reported to result in satisfactory surgical results. Two-stage operations have also been reported in the earlier literature.3,5,7 Combined approaches (e.g., cranial-orbital-zygomatic and anterior transpetrosal approaches or subtemporal and suboccipital approaches) carry the risk of venous injury and injury from excessive retraction. A slowly growing tumor within Meckel’s cave significantly increases the space and also widens the trigeminal pore opening to the posterior fossa. Because of the soft consistency of the tumor, total surgical removal of a large, multicompartment tumor may be achieved through a surgical approach from a single cranial fossa. Progressive removal through an expanded Meckel cave was first described by Al-Mefty and coauthors, who used an extradural zygomatic middle fossa approach.5 We have used the Dolenc extradural approach to achieve resection of the posterior fossa component (Figs. 144-3 and 144-4).24 A well-developed arachnoid plane between the tumor and lower cranial nerves forms a convenient cleavage plane and facilitates tumor resection. Although an anterior approach provides excellent access to the posterior fossa through the enlarged Meckel cave, the reverse is not the case, and hence a posterior fossa approach provides limited access to the portion of the tumor located in the middle fossa.5,24

Type D tumors originate from the maxillary and mandibular branches of the trigeminal nerve and extend into the infratemporal fossa through cranial foramina. This subgroup of tumors is exposed with a completely extradural, preauricular-infratemporal approach, which may be combined with temporal craniotomies if significant intracranial extension has occurred.7 During the procedure branches of the facial nerve and the internal carotid artery should be protected.

TSs are encapsulated tumors. As is the case with vestibular schwannomas, resection starts with an intracapsular debulking procedure, followed by careful microdissection from surrounding neurovascular structures. With a large TS, the CN VII-VIII complex is found stretched and caudally displaced on the tumor capsule. The internal carotid artery and oculomotor and abducens nerves are displaced medially, and CN IV is displaced cranially. The majority of tumors are well demarcated from surrounding neurovascular structures.3 In few cases, adherence to surrounding structures such as the brainstem may preclude total resection. Preservation of all the noninvolved nerve fascicles should be the goal of surgery.20

Role of Radiosurgery and Radiotherapy

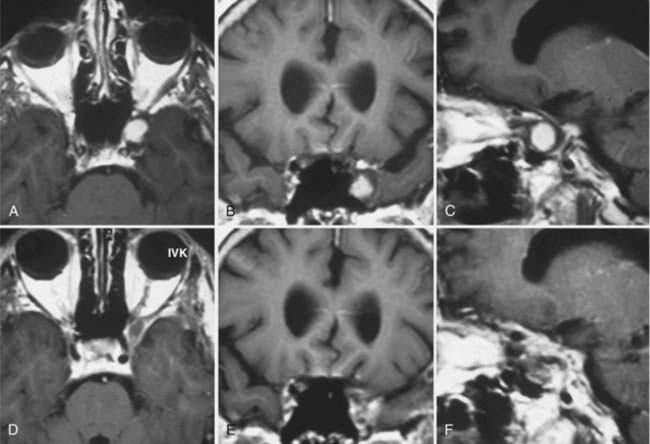

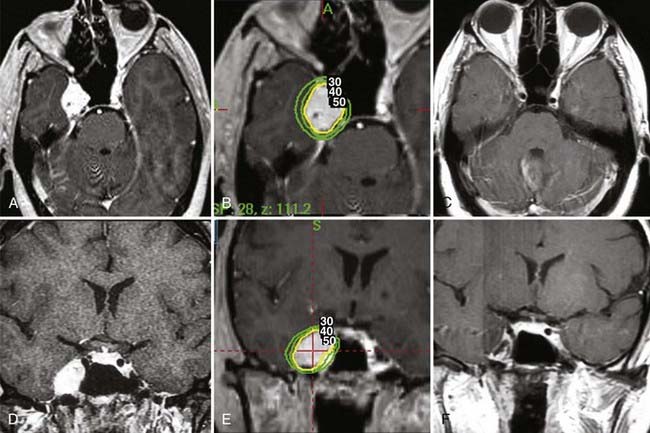

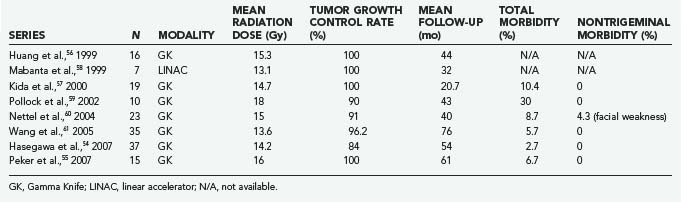

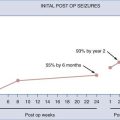

Several studies have shown that Gamma Knife radiosurgery is very effective in the treatment of TSs.54–57 Large, symptomatic TSs are best treated by surgical resection. Currently, radiosurgery is considered an important adjunct for residual and recurrent tumors smaller than 3 cm in diameter and in symptomatic patients in whom surgery caries a high risk for mortality and morbidity. Based on experience with vestibular schwannomas, which has demonstrated excellent long-term control of tumor growth and low morbidity, others have recommended radiosurgery as the primary treatment of small to medium-sized TSs (Fig. 144-5). The aim of radiosurgery is to achieve control of tumor growth without causing additional cranial nerve deficits. In the current literature, few series, totaling slightly more than 160 patients, have reported the results of radiosurgery (Table 144-2).54–61 The mean tumor dose in the reported series ranged from 13.1 to 18 Gy. Reported tumor control rates ranged from 84% to 100%.54–56,59,61 Similarly high tumor control rates were reported for linear accelerator–based radiosurgery.57 In most studies the follow-up period is fairly short, but the study by Wang and coauthors reported follow-up longer than 5 years in 74.5% of the patients and a similarly high tumor control rate of 96.2%.61 Fairly low morbidity rates were reported in various series, including facial hypoesthesia in 2.7% to 8.7%, facial pain in 2.9% to 8.7%, and trigeminal motor weakness in 2.9%.54–56,59,61

Fractionated external beam radiotherapy is used mainly for recurrent and inoperable TSs. Only two studies have reported the results of fractionated radiotherapy. Wallner and colleagues reported the results in 8 patients treated with 45 to 54 Gy in 1.6- to 1.8-Gy fractions.62 At follow-up ranging from 2 to 15 years, a 50% tumor control rate was achieved and the time to tumor recurrence ranged from 1.4 to 7 years. Zabel and associates reported the results of 13 patients who received a mean of 57.6 Gy in 1.8-Gy fractions.63 At a median follow-up of 33 months, the authors reported 100% tumor growth control.

Outcome

High mortality and morbidity rates have been reported in the first half of the 20th century. In their review of 39 patients reported before 1956, Schisano and Olivecrona found a 41% 1-year mortality rate.13 The advent of microsurgery significantly decreased the mortality rate, and the same authors reported a mortality rate of 5.3% in their 19 patients. Surgical results have improved even more after the popularization of skull base approaches.18 Today, with routine use of cranial base techniques, surgical resection of TSs is achieved with very low mortality and morbidity. Very high total resection rates ranging from 75% to 100% have been reported in the modern literature.2–4,15,20 Resection rates are comparable among different types of TS. Analysis of seven large studies that included 129 patients indicated that resection rates for Jefferson type A, B, and C TSs were 88%, 71%, and 81%, respectively.3,5–7,9,15,16 There is no solid evidence to indicate a risk for symptomatic recurrence in patients whose resection was subtotal. A high incidence of symptomatic tumor recurrence has been reported in some studies, whereas others have reported long remission periods.15 Therefore, close follow-up is warranted. In earlier literature, recurrence rates as high as 60% have been reported, even after total resection. This rate is especially high in cases with involvement of the cavernous sinus. In most recent studies reporting the use of skull base techniques, this rate was around 10%.5,7,18,20,24,37 Recurrent cases can be managed by reoperation, fractionated external beam radiotherapy, and radiosurgery.54–56 Surgical results for recurrent tumors are as good as those for primary tumors.1,9,15

The majority of, if not all, patients experience trigeminal nerve dysfunction in the immediate postoperative period after surgical resection of TSs.2,3,9 In most patients this trigeminal dysfunction is manifested in the form of hypoesthesia and resolves within weeks of surgery.2,9 In some cases it may be permanent. Preoperative facial pain and diplopia usually respond well to the surgical intervention. Operative complications include CSF leakage, infection, aseptic meningitis, hemorrhage in the tumor bed, vasospasm, hydrocephalus, and permanent cranial nerve injury.5,20,24

Conclusion

Al-Mefty O, Ayoubi S, Gaber E. Trigeminal schwannomas: removal of dumbbell-shaped tumors through the expanded Meckel cave and outcomes of cranial nerve function. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:453-463.

Day JD, Fukushima T. The surgical management of trigeminal neuromas. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:233-240.

Dolenc VV. Frontotemporal epidural approach to trigeminal neurinomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;130:55-65.

el-Kalliny M, van Loveren H, Keller JT, et al. Tumors of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:508-514.

Goel A, Muzumdar D, Raman C. Trigeminal neuroma: analysis of surgical experience with 73 cases. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:783-790.

Jefferson G. The trigeminal neurinomas with some remarks on malignant invasion of the gasserian ganglion. Clin Neurosurg. 1953;1:11-54.

McCormick PC, Bello JA, Post KD. Trigeminal schwannoma. Surgical series of 14 cases with review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:850-860.

Peker S, Bayrakli F, Kilic T, et al. Gamma-knife radiosurgery in the treatment of trigeminal schwannomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149:1133-1137.

VandeVyver V, Lemmerling M, Van Hecke W, et al. MRI findings of the normal and diseased trigeminal nerve ganglion and branches: a pictorial review. JBR-BTR. 2007;90:272-277.

1 Lesoin F, Rousseaux M, Villette L, et al. Neurinomas of the trigeminal nerve. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1986;82:118-122.

2 Dolenc VV. Frontotemporal epidural approach to trigeminal neurinomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1994;130:55-65.

3 Day JD, Fukushima T. The surgical management of trigeminal neuromas. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:233-240.

4 Goel A. Infratemporal fossa interdural approach for trigeminal neurinomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1995;136:99-102.

5 Al-Mefty O, Ayoubi S, Gaber E. Trigeminal schwannomas: removal of dumbbell-shaped tumors through the expanded Meckel cave and outcomes of cranial nerve function. J Neurosurg. 2002;96:453-463.

6 Yoshida K, Kawase T. Trigeminal neurinomas extending into multiple fossae: surgical methods and review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1999;91:202-211.

7 Samii M, Migliori MM, Tatagiba M, et al. Surgical treatment of trigeminal schwannomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:711-718.

8 Yasargil MG. Less common neurinomas: orbital, oculomotor, trigeminal, facial, glossopharyngeal, accessory and hypoglossal. In: Yasargil MG, editor. Microneurosurgery. New York: Thieme; 1995:124-131.

9 McCormick PC, Bello JA, Post KD. Trigeminal schwannoma. Surgical series of 14 cases with review of the literature. J Neurosurg. 1988;69:850-860.

10 Peet MM. Tumors of the Gasserian ganglion. With the report of two cases of extracranial carcinoma infiltrating the ganglion by direct extension through the maxillary division. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1927;44:202-207.

11 Frazier CH. An operable tumor involving the Gasserian ganglion. Am J Med Sci. 1918;156:483-490.

12 Cuneo HM, Rand CW. Tumors of the Gasserian ganglion. Tumor of the left Gasserian ganglion associated with enlargement of the mandibular nerve. J Neurosurg. 1952;9:423-431.

13 Schisano G, Olivecrona H. Neurinomas of the Gasserian ganglion and trigeminal root. J Neurosurg. 1960;17:306-322.

14 de Benedittis G, Bernasconi V, Ettorre G. Tumours of the fifth cranial nerve. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1977;38:37-64.

15 Pollack IF, Sekhar LN, Jannetta PJ, et al. Neurilemomas of the trigeminal nerve. J Neurosurg. 1989;70:737-745.

16 Yasui T, Hakuba A, Kim SH, Nishimura S. Trigeminal neurinomas: operative approach in eight cases. J Neurosurg. 1989;71:506-511.

17 Bordi L, Compton J, Symon L. Trigeminal neuroma. A report of eleven cases. Surg Neurol. 1989;31:272-276.

18 Taha JM, Tew JMJr, van Loveren HR, et al. Comparison of conventional and skull base surgical approaches for the excision of trigeminal neurinomas. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:719-725.

19 Konovalov AN, Spallone A, Mukhamedjanov DJ, et al. Trigeminal neurinomas. A series of 111 surgical cases from a single institution. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1996;138:1027-1035.

20 Sarma S, Sekhar LN, Schessel DA. Nonvestibular schwannomas of the brain: a 7-year experience. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:437-448.

21 Goel A, Muzumdar D, Raman C. Trigeminal neuroma: analysis of surgical experience with 73 cases. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:783-790.

22 Gwak HS, Hwang SK, Paek SH, et al. Long-term outcome of trigeminal neurinomas with modified classification focusing on petrous erosion. Surg Neurol. 2003;60:39-48.

23 Mariniello G, Cappabianca P, Buonamassa S, et al. Surgical treatment of intracavernous trigeminal schwannomas via a fronto-temporal epidural approach. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2004;106:104-109.

24 Pamir MN, Peker S, Bayrakli F, et al. Surgical treatment of trigeminal schwannomas. Neurosurg Rev. 2007;30:329-337.

25 Woodruff JM, Kourea HP, Louis DN, et al. Schwannomas. In: Kleihues P, Cavenee WK, editors. Pathology and Genetics of Tumors of the Nervous System. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2000:164-166.

26 Knudsen V, Kolze V. Neurinoma of the Gasserian ganglion and the trigeminal root. Report of four cases. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 1972;26:159-164.

27 Beck DW, Menezes AH. Lesions in Meckel’s cave: variable presentation and pathology. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:684-689.

28 Levy WJ, Ansbacher L, Byer J, et al. Primary malignant nerve sheath tumor of the gasserian ganglion: a report of two cases. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:572-576.

29 Hedeman LS, Lewinsky BS, Lochridge GK, et al. Primary malignant schwannoma of the Gasserian ganglion. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 1978;48:279-283.

30 Jefferson G. The trigeminal neurinomas with some remarks on malignant invasion of the gasserian ganglion. Clin Neurosurg. 1953;1:11-54.

31 Arseni C, Dumitrescu L, Constantinescu A. Neurinomas of the trigeminal nerve. Surg Neurol. 1975;4:497-503.

32 Westhout FD, Mathews M, Pare LS, et al. Recognizing schwannomatosis and distinguishing it from neurofibromatosis type 1 or 2. J Spinal Disord Tech. 2007;20:329-332.

33 Rhoton ALJr. Microsurgical anatomy of the posterior fossa cranial nerves. Clin Neurosurg. 1979;26:398-462.

34 Peker S, Kurtkaya O, Uzun I, et al. Microanatomy of the central myelin–peripheral myelin transition zone of the trigeminal nerve. Neurosurgery. 2006;59:354-359.

35 Paillas JE, Grisoli F, Farnarier P. [Trigeminal nerve neurinomas. Apropos of 8 cases.]. Neurochirurgie. 1974;20:41-54.

36 Yonas H, Jannetta PJ. Neurinoma of the trigeminal root and atypical trigeminal neuralgia: their commonality. Neurosurgery. 1980;6:273-277.

37 Pamir MN, Kilic T, Ozek MM, et al. Non-meningeal tumours of the cavernous sinus: a surgical analysis. J Clin Neurosci. 2006;13:626-635.

38 el-Kalliny M, van Loveren H, Keller JT, et al. Tumors of the lateral wall of the cavernous sinus. J Neurosurg. 1992;77:508-514.

39 Nager GT. Neurinomas of the trigeminal nerve. Am J Otolaryngol. 1984;5:301-333.

40 Del Priore LV, Miller NR. Trigeminal schwannoma as a cause of chronic, isolated sixth nerve palsy. Am J Ophthalmol. 1989;108:726-729.

41 Asari S, Tsuchida S, Fujiwara A, et al. Trigeminal neurinoma presenting with intratumoral hemorrhage: report of two cases. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 1992;94:219-224.

42 Sinha AK, Murty RK, Dinakar I. Trigeminal neurinoma with an apoplectic onset. Br J Neurosurg. 1997;11:431-432.

43 O’Reilly BF, Mehanna H, Kishore A, et al. Growth rate of non-vestibular intracranial schwannomas. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 2004;29:94-97.

44 Rigamonti D, Spetzler RF, Shetter A, et al. Magnetic resonance imaging and trigeminal schwannoma. Surg Neurol. 1987;28:67-70.

45 VandeVyver V, Lemmerling M, Van Hecke W, et al. MRI findings of the normal and diseased trigeminal nerve ganglion and branches: a pictorial review. JBR-BTR. 2007;90:272-277.

46 Majoie CB, Hulsmans FJ, Castelijns JA, et al. Primary nerve-sheath tumours of the trigeminal nerve: clinical and MRI findings. Neuroradiology. 1999;41:100-108.

47 Asari S, Katayama S, Itoh T, et al. CT and MRI of haemorrhage into intracranial neuromas. Neuroradiology. 1993;35:247-250.

48 Saito A, Nakazawa T, Matsuda M, et al. [Comparison of computed tomographic scanning and magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of trigeminal schwannoma. Report of four cases.]. Neurol Med Chir (Tokyo). 1989;29:1101-1106.

49 Naidich TP, Lin JP, Leeds NE, et al. Computed tomography in the diagnosis of extra-axial posterior fossa masses. Radiology. 1976;120:333-339.

50 Palacios E, MacGee EE. The radiographic diagnosis of trigeminal neurinomas. J Neurosurg. 1972;36:153-156.

51 Goldsher D, Litt AW, Pinto RS, et al. Dural “tail” associated with meningiomas on Gd-DTPA–enhanced MR images: characteristics, differential diagnostic value, and possible implications for treatment. Radiology. 1990;176:447-450.

52 Dolenc VV, Skrap M, Sustersic J, et al. A transcavernous-transsellar approach to the basilar tip aneurysms. Br J Neurosurg. 1987;1:251-259.

53 Krayenbuhl H. [Neurinoma of trigeminal nerve.]. Bull Schweiz Akad Med Wiss. 1959;15:89-100.

54 Hasegawa T, Kida Y, Yoshimoto M, Koike J. Trigeminal schwannomas: results of gamma knife surgery in 37 cases. J Neurosurg. 2007;106:18-23.

55 Peker S, Bayrakli F, Kilic T, et al. Gamma-knife radiosurgery in the treatment of trigeminal schwannomas. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2007;149:1133-1137.

56 Huang CF, Kondziolka D, Flickinger JC, et al. Stereotactic radiosurgery for trigeminal schwannomas. Neurosurgery. 1999;45:11-16.

57 Kida Y, Yoshimoto M, Hasegawa T, et al. Radiosurgery of epidermoid tumors with Gamma knife: possibility of radiosurgical nerve decompression. No Shinkei Geka. 2000;34:375-381.

58 Mabanta SR, Buatti JM, Friedman WA, et al. Linear accelerator radiosurgery for nonacoustic schwannomas. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 1999;43:545-548.

59 Pollock BE, Foote RL, Stafford SL. Stereotactic radiosurgery: the preferred management for patients with nonvestibular schwannomas? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;52:1002-1007.

60 Nettel B, Niranjan A, Martin JJ, et al. Gamma knife radiosurgery for trigeminal schwannomas. Surg Neurol. 2004;62:435-444.

61 Wang EM, Pan L, Zhang N, et al. Clinical experience with Leksell gamma knife in the treatment of trigeminal schwannomas. Chin Med J (Engl). 2005;118:436-440.

62 Wallner KE, Sheline GE, Pitts LH, et al. Efficacy of irradiation for incompletely excised acoustic neurilemomas. J Neurosurg. 1987;67:858-863.

63 Zabel A, Debus J, Thilmann C, et al. Management of benign cranial nonacoustic schwannomas by fractionated stereotactic radiotherapy. Int J Cancer. 2001;96:356-362.