CHAPTER 160 Trigeminal Neuralgia

Diagnosis and Nonoperative Management

Neuropathic facial pain (NFP) is defined as pain around the mouth or face that arises from a primary lesion or dysfunction of the nervous system.1 The management of NFP can be a frustrating as well as rewarding experience in neurosurgical practice because facial pain is often a difficult problem with a wide variety of potential causes. It is therefore important for neurosurgeons to have a broad understanding of the underpinnings of facial pain syndromes. NFP can be primary (with no recognizable underlying pathology) or secondary, such as following traumatic nerve injury. NFP includes a heterogeneous group of entities and can be broadly considered in two categories: paroxysmal and continuous.2 Paroxysmal neuropathies such as trigeminal neuralgia (TN) are characterized by short electrical shock-like or sharp pain. Continuous pain often has a burning characteristic and is a common feature of conditions such as postherpetic neuralgia (PHN). NFP can vary in severity and also commonly presents with thermal or mechanical allodynia.

Historical Perspective

One of the earliest known descriptions of paroxysmal facial pain was by the Arab physician Jurjani in the 11th century. He described “a type of pain which affects the teeth on one side and the whole of the jaw on the side which is painful.”3 The 17th century physician John Locke described the symptoms of TN in the wife of the English ambassador to France. Faced with limited treatment options for the patient’s excruciating pain, the physician opted for eight rounds of cleansing of the gastrointestinal tract, which reportedly resulted in remission of symptoms.4

In the era preceding the description of TN, studies of the anatomy of the cranial nerves led to a better understanding of facial pain. In 1829, the Scottish anatomist Sir Charles Bell (1774-1842) described the anatomy of the fifth cranial nerve and its motor and sensory functions, establishing the trigeminal nerve as the cranial nerve responsible for subserving facial sensation as well as motor innervation to the masticator muscles.5 Previously, it was widely believed that the seventh cranial nerve was the source of facial pain syndromes. Bell’s discovery shifted the focus of investigation of facial pain syndromes from the seventh to the fifth cranial nerve.3

An important breakthrough in the management of TN occurred fortuitously in 1942 when Bergouignan administered his patients the then new anticonvulsant diphenylhydantoin (phenytoin).6 Before this, the condition was referred to as neuralgia epileptiform owing to a prior hypothesis by Trousseau in 1853 that TN being paroxysmal was related to abnormal impulse conduction, analogous to epilepsy.7 When carbamazepine, a new medication for epilepsy was introduced in 1962, it was soon found to be useful in patients with TN.8,9 It had greater efficacy and less toxicity than the hydantoins and remains to this day the mainstay of medical therapy.10

General Principles in the Medical Management of Facial Pain

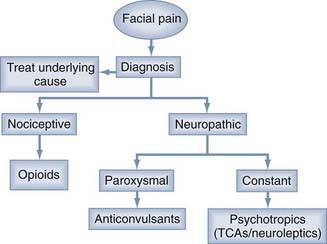

The initial treatment of most facial pain syndromes is medical. The differential diagnosis of facial pain includes pathology involving nerves, teeth and jaw, sinuses, the aerodigestive tract, and blood vessels and is summarized in Table 160-1. Treatment must be driven by proper diagnosis and the characteristic features of the pain (Fig. 160-1). Pain due to head or neck neoplasm is best treated by treatment of the lesion. Similarly, psychogenic pain is best managed by treatment of the underlying psychiatric condition. It is important to distinguish nociceptive from neuropathic pain. Nociceptive pain is caused by normal and appropriate neural activity in the setting of local tissue injury (e.g., trauma, malignancy, infection). Nociceptive pain is typically constant and aching and only occasionally paroxysmal. Besides appropriate management of the underlying condition, nociceptive pain is best managed by opioid medications.

| LOCATION OF LESION | CONDITION |

|---|---|

| Nerve | Trigeminal neuralgia, postherpetic neuralgia, trigeminal neuropathic pain, glossopharyngeal neuralgia, sphenopalatine neuralgia, geniculate neuralgia (Ramsay Hunt syndrome), multiple sclerosis, cerebellopontine angle tumor |

| Teeth and jaw | Dentinal, pulpal, or periodontal pain; temporomandibular joint disorders |

| Sinuses and aerodigestive tract | Sinusitis, head and neck cancer, inflammatory lesions |

| Eyes | Optic neuritis, iritis, glaucoma |

| Blood vessels | Giant cell arteritis, migraine, cluster headache, Tolosa-Hunt syndrome |

| Psychological | Psychogenic, atypical facial pain |

Trigeminal Neuralgia

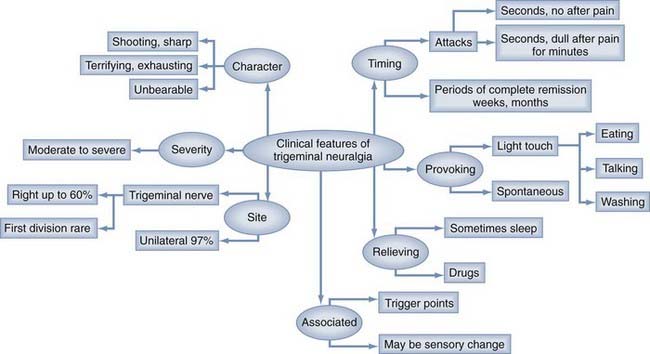

TN, a neuropathic pain syndrome, is defined by the International Association for the Study of Pain (ISAP) as “a sudden and usually unilateral severe brief stabbing recurrent pain in the distribution of one or more branches of the fifth cranial nerve.” It is an excruciating, short-lasting (<2 minutes), unilateral facial pain that may be spontaneous or triggered by gentle, innocuous stimuli and separated by pain-free intervals of varying duration (Fig. 160-2).

FIGURE 160-2 Major clinical features of trigeminal neuralgia.

(From Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Zakrzewska JM, ed. Orofacial Pain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008, pp 119-134.)

Most TN patients (>85%) have classic TN. Diagnosis in typical cases is often straightforward; however, most TN patients suffer from misdiagnosis. Common conditions that mimic TN as well as their presenting features are listed in Table 160-2.

TABLE 160-2 Common Conditions that Mimic Trigeminal Neuralgia

| DIAGNOSIS | IMPORTANT FEATURES |

|---|---|

| Dental infection or cracked tooth | Well localized to tooth; local swelling and erythema; appropriate findings on dental examination |

| Temporomandibular joint pain | Often bilateral and may radiate around ear and to neck and temples; jaw opening may be limited and can produce an audible click |

| Persistent idiopathic facial pain (previously called atypical facial pain) | Often bilateral and may extend out of trigeminal territory; pain often continuous, mild to moderate in severity, and aching or throbbing in character |

| Migraine | Often preceded by aura; severe unilateral headache often associated with nausea, photophobia, phonophobia, and neck stiffness |

| Postherpetic neuralgia | History of herpes zoster or vesicular outbreak |

| Temporal arteritis | Common in elderly people; temporal pain should be constant and often associated with jaw claudication, fever, and weight loss; temporal arteries may be firm, tender, and nonpulsatile on examination |

Adapted from Bennetto L, Patel NK, Fuller G. Trigeminal neuralgia and its management. BMJ. 2007;334:201-205.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Considerable progress has been made in elucidating the etiology of TN. In most patients with classic TN, the pain is generated because of compression of the trigeminal nerve most commonly at the root entry zone by an artery or vein. Observations supporting this are summarized in Table 160-3. The plaques of demyelination lead to hyperexcitability of injured afferents, which results in after discharges large enough to result in a non-nociceptive signal being perceived as pain.11 One theory to explain TN is the one proposed by Devor and colleagues,12 called the ignition theory, which can be explained as follows. The triggering of pain in TN may follow innocuous stimuli, a phenomenon that is probably explained by postinjury changes in neuronal function. After nerve injury, there is an increased proportion of A-beta fibers with subthreshold oscillations that ultimately generate ectopic discharges.13–15 These produce a transient depolarization in neighboring passive C neurons in the same ganglion.16 These findings favor a mechanism whereby afferent nociceptors could be stimulated by activity in injured low-threshold mechanoreceptors. It is likely that both central and peripheral changes occur, which would explain why not all patients with a treated compression of the nerve get permanent relief. There are likely other factors involved given the rarity of the disease, and there are reports of genetic and familial forms.17,18

TABLE 160-3 Evidence of Neurovascular Compression as Causative for Trigeminal Neuralgia

|

• An aberrant loop of artery, or less commonly vein, is found to be compressing the root entry zone of the trigeminal nerve in 80% to 90% of patients at surgery.

|

Adapted from Bennetto L, Patel NK, Fuller G. Trigeminal neuralgia and its management. BMJ. 2007;334:201-205.

Epidemiology

TN is considered a rare condition with the following features:

A recent study using general practice research databases in the United Kingdom and very broad diagnostic criteria that may have allowed inclusion of neuropathic facial pain syndrome other than TN suggested a higher prevalence of 26 per 100,000.19

Risk Factors

The major risk factor for TN is multiple sclerosis.11 Hypertension may play a role but is common in the age group at risk. Familial tendency is rare but has been reported.17,18 Bilateral involvement is present in only 5% of cases, and sensory deficits are usually subtle and partial and are associated with either chronicity of the syndrome or a history of prior surgical intervention.20,21 In a retrospective study by Pollock and colleagues,21 patients with bilateral TN were more commonly females (74% versus 58%; P < .1), had a higher rate of “familial” TN (17% versus 4.1%; P < .001), and had a greater increased incidence of additional cranial nerve dysfunction (17% versus 6.6%; P < .05) and hypertension (34% versus 19%; P < .05). Early, significant, and nonsurgical sensory loss, in addition to bilateral involvement, should trigger a thorough investigation for symptomatic (i.e., secondary) TN.

Clinical Features

Diagnostic criteria for classic TN have been described in the International Classification of Headache Disorders (Table 160-4). These include paroxysmal attacks of pain, characterized as intense, sharp, superficial, or stabbing precipitated from trigger areas or by trigger factors, similar attacks in a patient, absence of neurological findings, and absence of other demonstrable cause. However, these criteria have not been validated.22 The most problematic feature of the diagnostic criteria is a requirement for absence of sensory deficit in the absence of prior surgical intervention history. There is abundant evidence that subtle clinically detectable sensory deficits are present in the setting of typical TN as well as evidence that electrophysiologic abnormalities may antedate detectable sensory loss on examination.23–27 There are other forms of TN that most frequently have been called atypical trigeminal neuralgia and trigeminal neuropathy. Because there are no long-term cohort studies, it is not possible to determine whether these atypical forms are in fact the same condition but further on in the natural history or whether they may represent a distinct condition.

TABLE 160-4 Diagnostic Criteria for Classic Trigeminal Neuralgia

|

• Paroxysmal attacks of pain lasting from a fraction of a second to 2 minutes that affect one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve

|

Adapted from Bennetto L, Patel NK, Fuller G. Trigeminal neuralgia and its management. BMJ. 2007;334:201-205.

The timing of the attacks and remission periods, as well as the character of the pain, are the distinguishing features for classic TN. Many patients with increased pain severity during the day and only one third of patients will report nocturnal pain resulting in awakening.11 Patients with atypical TN often describe a burning, dull, aching after pain that is persistent, followed by a completely pain-free interval.11

Quality of life in TN can be severely impaired. Because the attacks are usually spontaneous and provoked when eating or talking, this reduces the ability to relax and enjoy social activity. Depression is common, and suicides have been reported.11

Although on routine examination most patients have no sensory deficit, existing minor sensory deficits may be very subtle and may increase in frequency with chronicity of the syndrome. Abnormalities in neurophysiologic testing may identify subclinical deficits.25–27 Patients may exhibit tactile trigger areas within the trigeminal distribution, which will precipitate an attack when stimulated. There are no autonomic features.

Ancillary Tests

The diagnosis of TN is purely clinical. However, hematologic and biochemical monitoring is important in patients on drug therapy (see later). Radiologic investigations are important to differentiate between symptomatic and idiopathic TN. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is useful to rule out secondary TN (e.g., neoplasms, cysts, vascular pathologies, multiple sclerosis plaques, lacunar infarctions). MRI does not have sufficient positive or negative predictive value to assess vascular compression as an etiology for the syndrome. Sensory testing is not done routinely, but quantitative sensory testing (QST) and evoked potentials may play an important role in differentiating between symptomatic and idiopathic TN.26,27

Medical Management

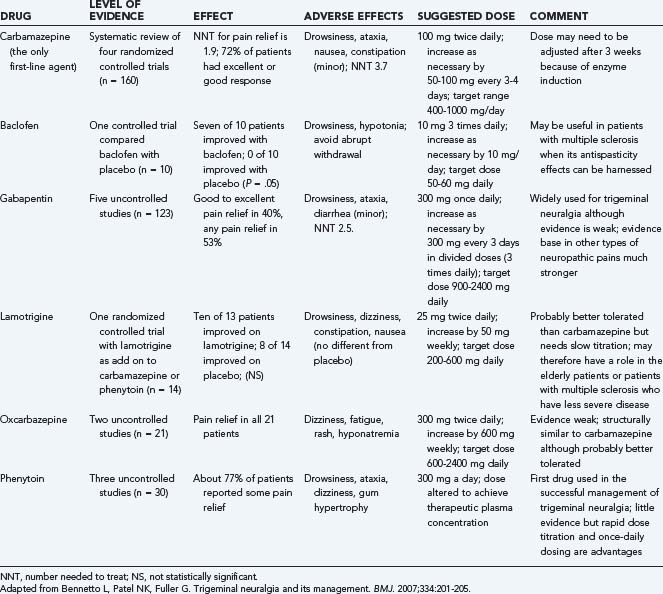

All patients with TN are initially managed medically. Medical management begins with a comprehensive history and physical examination, including baseline measure of pain and quality of life. Psychological support is important, and patients should be provided information about support groups. Key points in the management of patients with TN are summarized in Table 160-5. Commonly used drugs are carbamazepine, oxcarbazepine, gabapentin, lamotrigine, and baclofen. The evidence for their use is summarized in Table 160-6. Patients should keep pain diaries and change their drug levels to adjust to the changing severity of the pain and tolerability of side effects. Most of the drugs need to be escalated and withdrawn slowly to avoid side effects.

TABLE 160-5 Key Points in the Management of Patients with Trigeminal Neuralgia

Carbamazepine is the drug of choice, with good evidence to show that this drug is highly effective.1 Common adverse effects include drowsiness, dizziness, constipation, ataxia, and syndrome of inappropriate diuretic hormone (NNT, 3; 95% confidence interval, 2 to 4), although most can continue taking the drug.28 Other adverse effects include rashes, leukopenia, and abnormal liver function tests. The efficacy of the drug may diminish with long-term use.29 The pharmacokinetics of the drug also result in numerous drug interactions, and one of special note is that with warfarin. If the patient responds well, a controlled-release preparation can be substituted, and the dose can gradually be reduced. What is less clear is what to do if a patient is intolerant or allergic to carbamazepine, or if the drug is ineffective. In the absence of clear evidence of the effectiveness of other drugs, the choice among other agents can be made on the basis of adverse effects and ease of use.

Oxcarbazepine is a prodrug of carbamazepine with similar efficacy of pain control.30 Although it is of similar efficacy to carbamazepine, it is much better tolerated and results in fewer drug interactions.31 Long-term follow-up has also shown that the drug is safe but gradually loses its efficacy because of either development of tolerance or increase in severity of the disease.32

Gabapentin is widely used for neuropathic pain, although it lacks evidence in TN. Use of gabapentin therefore relies on the similarities between TN and other neuropathic pain syndromes, rather than their obvious differences.10 A recent randomized controlled trial suggests that gabapentin, combined with repeated topical injections of ropivacaine, gives better pain control than gabapentin on its own.33 Familiarity with use of gabapentin in other neuropathic pain syndromes has led many clinicians to choose this as a second-line drug for TN.34

Pregabalin has been licensed for use in neuropathic pain and has been reported to be effective in a cohort series in TN.35 Clonazepam, valproate, and phenytoin are often used. There are no high-quality studies on the use of polypharmacy as often practiced in epilepsy. Topical injections of lidocaine into trigger points can give some temporary relief. Drugs such as tocainide, tizanidine, and pimozide are ineffective or their side-effect profile is severe enough to exclude their use.36–38

Prognosis

Untreated, TN becomes gradually more severe with fewer remission periods, but the rate at which this occurs is unpredictable. Spontaneous remission periods of up to 6 months are common, yet the syndrome remains predominantly progressive in nature.29,32 Up to 44% of patients when followed for up to 16 years will fail to get complete pain relief with medical therapy.29

. The International Classification of Headache Disorders: 2nd edition. Anonymous. Cephalalgia. 2004;24;:9-160.

He L, Wu B, Zhou M. Non-antiepileptic drugs for trigeminal neuralgia. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;3:CD004029.

Jorns TP, Zakrzewska JM. Evidence-based approach to the medical management of trigeminal neuralgia. Br J Neurosurg. 2007;21:253-261.

Lewis MA, Sankar V, De Laat A, et al. Management of neuropathic orofacial pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(suppl 32):e1-e24.

Lopez BC, Hamlyn PJ, Zakrzewska JM. Systematic review of ablative neurosurgical techniques for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 2004;54:973-982.

Merskey H, Bogduk N. Classification of Chronic Pain. Descriptors of Chronic Pain Syndromes and Definitions of Pain Terms, 2nd ed. Seattle: IASP Press; 1994. 1-222

www http://www.cks.library.nhs.uk/.

Nurmikko TJ, Eldridge PR. Trigeminal neuralgia—pathophysiology, diagnosis and current treatment. Br J Anaesth. 2001;87:117-132.

Spatz AL, Zakrzewska JM, Kay EJ. Decision analysis of medical and surgical treatments for trigeminal neuralgia: how patient evaluations of benefits and risks affect the utility of treatment decisions. Pain. 2007;131:302-310.

Weigel G, Casey KF. Striking Back: The Trigeminal Neuralgia and Face Pain Handbook. Gainesville: The Trigeminal Neuralgia Association; 2004.

Wiffen P, Collins S, McQuay H, et al. Anticonvulsant drugs for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD001133.

Wiffen PJ, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Carbamazepine for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD005451.

Zakrzewska JM. Insight: Facts and Stories behind Trigeminal Neuralgia. Gainesville: Trigeminal Neuralgia Association; 2006. 1-403

Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Zakrzewska JM, editor. Orofacial Pain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008:119-134.

Zakrzewska JM, Lopez BC. Trigeminal neuralgia. BMJ Clinical Evidence Concise, 462-464, or www.clinicalevidence.com, 2006.

1 Lewis MA, Sankar V, De Laat A, et al. Management of neuropathic orofacial pain. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod. 2007;103(suppl 32):e1-e24.

2 Okeson JP. Orofacial Pain: Guidelines for Assessment, Classification, and Management. Chicago, IL: The American Academy of Orofacial Pain, Quintessence Publishing; 1996.

3 Youkilis AS, Sagher O. Diagnosis and nonoperative management of trigeminal neuralgia. Winn HR, editor. Youman’s Neurological Surgery. 5th ed. 2004:2987-2995.

4 Stookey BR. Trigeminal Neuralgia. Springfield, Ill: Charles C. Thomas; 1959.

5 Bell C. On the nerves of the face. Phil Trans R Soc (Lond). 1829;1:317-330.

6 Bergouignan M. Cures hereuses de neuralgie facilaes essentielles par le diphenylhydantoinate de soude. Rev Laryngol Otol Rhinol. 1942;63:34-41.

7 Trousseau A. De la neuralgie epileptiforme. Arch Gen Med. 1853;1:33-44.

8 Blom S. Trigeminal neuralgia. Its treatment with a new anticonvulsant drug (G-32883). Lancet. 1962;1:839-840.

9 Blom S. Tic douloureaux treated with a new anticonvulsant. Arch Neurol. 1962;9:285-290.

10 Zakrzewska JM, Linskey ME. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Zakrzewska JM, editor. Orofacial Pain. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008:119-134.

11 Bennetto L, Patel NK, Fuller G. Trigeminal neuralgia and its management. BMJ. 2007;334:201-205.

12 Devor M, Amir R, Rappaport ZH. Pathophysiology of trigeminal neuralgia: the ignition hypothesis. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:4-13.

13 Amir R, Michaelis M, Devor M. Membrane potential oscillations in dorsal root ganglion neurons: role in normal electrogenesis and neuropathic pain. J Neurosci. 1999;19:8589-8596.

14 Liu CN, Michaelis M, Amir R, et al. Spinal nerve injury enhances subthreshold membrane potential oscillations in DRG neurons: relation to neuropathic pain. J Neurophysiol. 2000;84:205-215.

15 Liu CN, Wall PD, Ben-Dor E, et al. Tactile allodynia in the absence of C-fiber activation: altered firing properties of DRG neurons following spinal nerve injury. Pain. 2000;85:503-521.

16 Amir R, Devor M. Functional cross-excitation between afferent A- and C-neurons in dorsal root ganglia. Neuroscience. 2000;95:189-195.

17 El Otmani H, Moutaouakil F, Fadel H, et al. Familial trigeminal neuralgia. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2008;164:384-387.

18 Duff JM, Spinner RJ, Lindor NM, et al. Familial trigeminal neuralgia and contralateral hemifacial spasm. Neurology. 1999;13(53):216-218.

19 Hall GC, Carroll D, Parry D, et al. Epidemiology and treatment of neuropathic pain: the UK primary care perspective. Pain. 2006;122:156-162.

20 Barker FGIII, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ, et al. The long-term outcome of microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:1077-1083.

21 Pollack IF, Jannetta PJ, Bissonette DJ. Bilateral trigeminal neuralgia: a 14-year experience with microvascular decompression. J Neurosurg. 1988;68:559-565.

22 Olesen J, Bousser MG, Diener HC, et al. The international classification of headache disorders, 2nd edition. Cephalalgia. 2004;24(suppl 1):24-150.

23 Sinay VJ, Bonamico LH, Dubrovsky A. Subclinical sensory abnormalities in trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia. 2003;23:541-544.

24 Bowsher D, Miles JB, Haggett CE, et al. Trigeminal neuralgia: a quantitative sensory perception threshold study in patients who had not undergone previous invasive procedures. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:190-192.

25 Nurmikko TJ. Altered cutaneous sensation in trigeminal neuralgia. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:523-527.

26 Bennett MH, Jannetta PJ. Evoked potentials in trigeminal neuralgia. Neurosurgery. 1983;13:242-247.

27 Mursch K, Schafer M, Steinhoff BJ, et al. Trigeminal evoked potentials and sensory deficits in atypical facial pain—a comparison with results in trigeminal neuralgia. Funct Neurol. 2002;17:133-136.

28 Wiffen PJ, McQuay HJ, Moore RA. Carbamazepine for acute and chronic pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2005;3:CD005451.

29 Taylor JC, Brauer S, Espir ML. Long-term treatment of trigeminal neuralgia with carbamazepine. Postgrad Med J. 1981;57:16-18.

30 Liebel JT, Menger N, Langohr H. Oxcarbazepine in der Behandlung der Trigeminusneuralgie. Nervenheilkunde. 2001;20:461-465.

31 Beydoun A, Schmidt D, D’Souza J. Oxcarbazepine versus carbamazepine in trigeminal neuralgia: a meta-analysis of three double blind comparative trials. Neurology. 2002;58(suppl 3):831-832.

32 Zakrzewska JM, Patsalos PN. Long-term cohort study comparing medical (oxcarbazepine) and surgical management of intractable trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 2002;95:259-266.

33 Lemos L, Flores S, Oliveira P, et al. Gabapentin supplemented with ropivacain block of trigger points improves pain control and quality of life in trigeminal neuralgia patients when compared with gabapentin alone. Clin J Pain. 2008;24:64-75.

34 Cheshire WPJr. Defining the role for gabapentin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia: a retrospective study. J Pain. 2002;3:137-142.

35 Obermann M, Yoon MS, Sensen K, et al. Efficacy of pregabalin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia. 2008;28:174-181.

36 Lindstrom P, Lindblom V. The analgesic effect of tocainide in trigeminal neuralgia. Pain. 1987;28:45-50.

37 Vilming ST, Lyberg T, Latase X. Tizanidine in the management of trigeminal neuralgia. Cephalalgia. 1986;6:181-182.

38 Lechin F, van der Dijs B, Lechin ME. Pimozide therapy for trigeminal neuralgia. Arch Neurol. 1989;46:960-963.