Chapter 48 Trigeminal Neuralgia

• Trigeminal neuralgia is a stereotyped, repetitive, unilateral, electric-shock-like facial pain triggered by non-noxious stimulation with clear pain-free intervals. Tic pain is ordinarily spontaneous in onset, but can frequently be triggered by a non-noxious stimulus.

• Continuous pain without a shock-like quality or a cranial nerve deficit raises the suspicion of diseases other than trigeminal neuralgia. Tic douloureux can be caused by any of a number of conditions affecting the ipsilateral trigeminal system. In the vast majority, the cause seems to be compression of the trigeminal nerve at its exit from the pons by an adjacent artery or vein that has elongated and kinked to become wedged against the nerve. In about 1% to 2% of cases, the pain results from a benign tumor in the cerebellopontine angle, and approximately 1% to 8% of patients with trigeminal neuralgia have multiple sclerosis.

• The diagnosis of tic douloureaux is based on the patient’s history of pain as no diagnostic imaging or physiological studies currently available will substitute for the history. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and magnetic resonance angiography (MRA) have improved the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing neurovascular compression of the nerve by evaluating the anatomical relationships of the arterial and venous structures with the trigeminal nerve at the root entry zone in the cerebellopontine angle. However, MRI is used primarily as a perioperative adjunct after the clinical diagnosis is made.

• Medical management of tic pain is successful in about 50% of patients and remains the initial approach. The anticonvulsants carbamazepine, phenytoin, and gabapentin appear to be the most effective in controlling the pain of tic douloureux.

• A multimodality approach, including various medical, surgical, or radiosurgical therapies, is most beneficial to patients with tic pain. Gasserian gangliolysis selectively destroys the nocireceptive fibers while preserving the touch fibers. This procedure can be performed using radiofrequency ablation, balloon compression, or glycerol. The success of radiosurgery appears excellent, although long-term recurrence rates are unclear. Of all surgical treatments, microvascular decompression is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence and sensory loss but carries low but significant morbidity rates.

Trigeminal neuralgia, also known as tic douloureux, is an excruciatingly painful condition that is most common in people aged 50 to 70 years. It is a stereotyped, repetitive, unilateral, electric-shock-like facial pain triggered by non-noxious stimulation with clear pain-free intervals.1–5 The incidence of trigeminal neuralgia is 4 to 5 per 100,000 population (median age 67 years).6 It involves the right side of the face more often than the left side, at a ratio of about 3:2. Women are more often affected than men in a ratio that has varied from 2:1 to 4:3 in reported series.7

Etiology and Pathogenesis

Tic douloureux can be caused by any of a number of conditions affecting the ipsilateral trigeminal system. In the vast majority, the cause seems to be compression of the trigeminal nerve at its exit from the pons by an adjacent artery or vein that has elongated and kinked to become wedged against the nerve. In about 1% to 2% of cases, the pain results from a benign tumor in the cerebellopontine angle, such as a meningioma, epidermoid tumor, or acoustic neuroma, or even an arteriovenous malformation.8 Other authors have indicated that 1% to 8% of patients with trigeminal neuralgia have multiple sclerosis.9–13 Very infrequently, trigeminal neuralgia may be the presenting symptom of multiple sclerosis.14 A variety of other rare etiological associations have been reported, but all of these together probably do not account for more than a low percentage of cases. In a significant number of patients, the cause of the tic douloureux is not apparent.

The pathogenesis of trigeminal neuralgia remains uncertain, as are the mechanisms by which treatments are effective. For example, some authors have postulated that nerve root demyelination resulting from neural compression by a blood vessel or tumor or resulting from multiple sclerosis is an important feature, perhaps permitting ephaptic transmission or ectopic impulse generation between adjacent denuded axons. Both peripheral and central mechanisms are most likely required for the production of tic douloureux. Calvin and colleagues presented a comprehensive theory that utilizes two known physiological mechanisms: the trigeminal dorsal root reflex and repetitive firing of extra action potentials from a focal region of altered axonal size or myelination.15 Altered central connectivity and neuronal hyperactivity caused by deafferentation (centralist concept) as well as changes in the trigeminal myelin and axons can lead to altered peripheral sensitivity to chemical and mechanical stimuli (peripheralist concept).15,16 However, as attractive as such ideas are, no theory has yet been postulated that explains all aspects of tic douloureux, such as the pain-free periods, which may last for months or years early in the course of the condition, the triggering of tic pain by non-noxious stimuli, the separation of the trigger areas from the painful region, and the response to anticonvulsants. Elimination of root compression by adjacent vessels does not take into account the effectiveness of numerous other surgical procedures, most of which injure the root or ganglion, but decompression of the root may relieve pain by facilitating remyelination.

Clinical Features

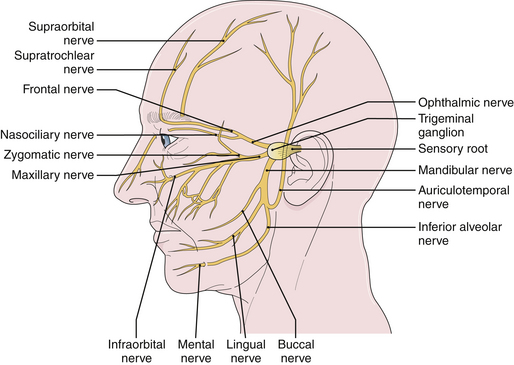

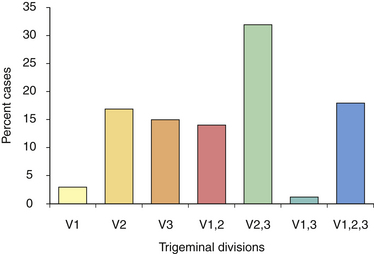

Tic douloureux is diagnosed almost exclusively on the basis of the patient’s history (Box 48.1). The International Headache Society defined trigeminal neuralgia as a “sudden, usually unilateral, severe, brief, stabbing, and recurrent pain in the distribution of one or more branches of the fifth cranial nerve.”17,18 The three divisions of the trigeminal nerve are the ophthalmic, maxillary, and mandibular. For the accurate diagnosis of facial pain, a detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the fifth cranial nerve is essential. By definition, the pain of tic douloureux is confined to the distribution of one trigeminal nerve (Fig. 48.1) and more commonly affects the lower part of the face than the upper.16 The maxillary division of the fifth cranial nerve (V2) is the site of pain alone or in combination with other divisions, most commonly the mandibular division (V3) in 45% of cases. The ophthalmic division (Vl) is least likely to be affected in trigeminal neuralgia (Fig. 48.2). A small number of patients have similar pain syndromes in the territories of the nervus intermedius, glossopharyngeal nerve, or vagus nerve. The pain of untreated tic douloureux occurs unpredictably and is sudden in onset, severe in degree, and short in duration. Often the patient can experience many paroxysms of pain within a single hour, and such bouts may go on for days, with some fluctuation in frequency from hour to hour and day to day. Early in the course of the syndrome, pain-free periods lasting months are common, but as time goes on these natural remissions tend to become less frequent and less prolonged. Although tic pain is ordinarily spontaneous in onset, it can frequently be triggered by a non-noxious stimulus, such as touching the skin on that side of the face, chewing, swallowing, or talking. Some patients are sensitive in certain areas of the face, called trigger zones, which when touched cause an attack of pain. Even a gentle breeze can trigger pain in some patients. The pain has been described as lancinating, lightning-like, or electrical in quality, and has been likened to the pain experienced when a dentist drills into the pulp of a tooth.7 The patient may wince in response to the pain, hence the name tic douloureux. A history of bilateral tic pain can be elicited in 3% of patients, although no patient has bilateral tic pain during one episode.16

BOX 48.1 International Headache Society Criteria for Trigeminal Neuralgia

Paroxysmal attacks of frontal pain last a few seconds to less than 2 minutes.

Pain has at least four of the following characteristics: distribution along one or more divisions of the trigeminal nerve; sudden, intense, sharp, superficial, stabbing or burning in quality; pain intensity severe; precipitation from trigger areas or by certain daily activities such as eating, talking, washing the face or cleaning the teeth; between paroxysms the patient is entirely asymptomatic.

No neurological deficit is found.

Attacks are stereotyped in the individual patient.

Other causes of facial pain are excluded by history, physical examination, and special investigation when necessary.

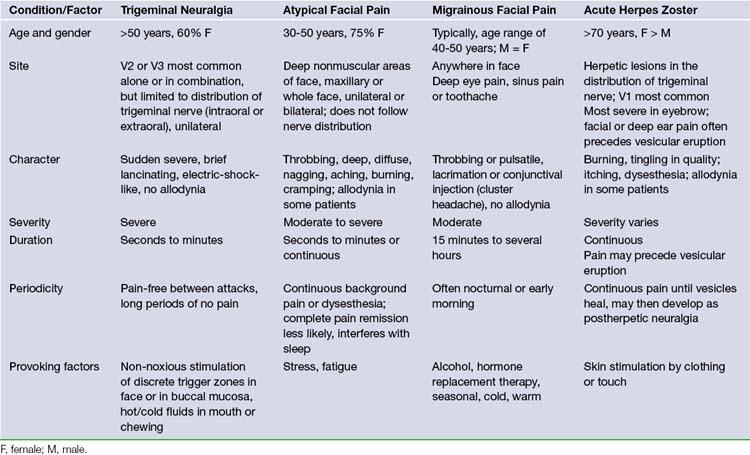

FIGURE 48.2 Distribution of pain among divisions of the trigeminal nerve in patients with tic douloureux

(Data from Loeser J. Tic douloureux. Pain Res Manage 2001;6:156-165.)

Often the patient who develops tic douloureux sees the dentist first, because lancinating lower facial pain seems to be arising from a certain tooth or teeth. Dentists are often fixated on peripheral lesions as the cause for pain. A diseased tooth in the upper jaw can cause headache on the same side, which may radiate into the orbit or face. A diseased tooth in the lower jaw may cause considerable pain in the distribution of the mandibular division of the nerve, including pain deep in the ear. In addition, dental pain is much more common than tic douloureux. Teeth may be extracted or other dental procedures performed without providing any relief of the pain of tic douloureux. The patient may also consult more than one physician before the correct diagnosis is made. In the majority of patients, the trigeminal neuralgia is idiopathic in that there is no identifiable cause.8 However, the presence of sensory loss mandates a thorough search for structural pathology. Patients with idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia can develop more atypical features with time in the absence of efficacious therapy. In all likelihood, this development coincides with ongoing neuropathic injury. Pain that is continuous, lacks a shock-like quality, or is associated with objective evidence of cranial nerve dysfunction should raise the suspicion of diseases other than idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. However, the most likely cause of this type of pain is a prior ablative procedure that damages the trigeminal nerve. Atypical facial pain is described as deep, burning, and continual. There is no jabbing onset as occurs in tic douloureux. The pain can radiate behind the ear, down onto the neck, or across to the opposite maxillary area. These patients, in contrast, often clutch their face, unlike the patient with tic douloureux who shields her face but is very careful not to actually touch it (Table 48.1). Myofascial pains involving the muscles of mastication and temporomandibular joint pain occur predominantly in the lateral face. They are also described as aching, burning, or cramping pains, and are often associated with tenderness to palpation of the involved muscles.16

Diagnosis

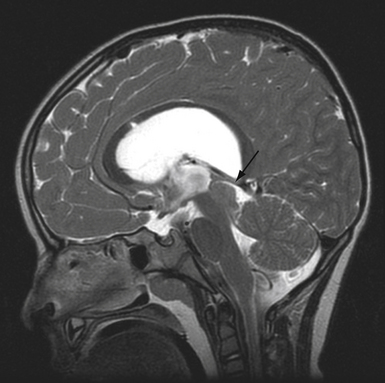

The diagnosis of tic douloureux is based almost exclusively on the history; as this disease consists only of pain, no diagnostic imaging or physiological studies currently available will substitute for the history. The neurological examination is ordinarily normal except for mild sensory changes in a minority of patients in the region of their pain, with the exception that those few patients with multiple sclerosis or a large structural lesion such as a tumor in the cerebellopontine angle usually have altered trigeminal sensation and other evidence that heralds the underlying disorder. Traditionally, diagnostic radiological studies such as computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging have been normal in the usual patient with tic douloureux, but they have been performed to identify the exceptional patient with a recognizable etiological condition such as those just mentioned.7 Patients with a Chiari malformation may also develop trigeminal neuralgia, thought to be the result of venous or arterial compression of the cranial nerves along with the tonsillar ectopia. Recent advances in magnetic resonance imaging and magnetic resonance angiography have improved the sensitivity and specificity of diagnosing neurovascular compression of the nerve by evaluating the anatomical relationships of the arterial and venous structures with the trigeminal nerve at the root entry zone in the cerebellopontine angle.16 However, so far these studies have been more used as a preoperative adjunct than for diagnostic purposes.19,20 Continued development of MRI is likely to lead to the ability to discern if there is a vascular impingement on the nerve and thereby may influence choice of treatment.

Treatment

Medication

The initial treatment of patients with trigeminal neuralgia is always pharmacological.21 Drugs with anticonvulsive properties rather than analgesic ones are most effective. There are a limited number of controlled trials that have studied the pharmacological treatment for trigeminal neuralgia. The anticonvulsants carbamazepine, phenytoin, and gabapentin have been found to reduce or control the pain of tic douloureux.22 Likewise, oxcarbazepine, lamotrigine, and baclofen are said to have beneficial effects in the treatment of tic douloureux, although the evidence is very limited.

Carbamazepine is considered the first-line treatment for patients with trigeminal neuralgia and is ordinarily begun at a dosage of 200 mg per day, being increased as tolerated to 200 mg three or four times a day, or more. Over 70% of patients report symptomatic improvement, although it is not an analgesic and must be taken regularly to maintain its efficacy. The goal is to reach the smallest dose that provides adequate pain relief. At high doses, the patient may experience the side effects of lethargy, sluggish thinking, and imbalance.7 Doses higher than 1800 mg have not been more effective.23 Carbamazepine may also interfere with the production of blood elements and may alter hepatic function. Therefore, a patient being treated with carbamazepine should have periodic complete blood counts and hepatic function studies. Oxcarbazepine is another anticonvulsant that has become popular recently, because it may be dosed less frequently and has fewer side effects than carbamazepine, although it appears to have the same efficacy. When patients have been pain free for several weeks, carbamazepine may be tapered, which should be done very slowly over weeks.

Phenytoin is ordinarily begun at a dosage of 100 mg three times a day. Intravenous phenytoin has been used in some patients for acute exacerbations with frequent, easily triggered, high-intensity pain attacks. Approximately 25% of patients obtain satisfactory pain relief although, unlike epilepsy, relief of tic douloureux pain has been shown to correlate with phenytoin blood levels. Coadministered carbamazepine can raise serum phenytoin concentrations, whereas phenytoin can decrease the half-life of carbamazepine.

Baclofen, a GABA analog, can also be used alone or in combination with phenytoin or carbamazepine. Other agents include clonazepam, valproic acid, lamotrigine, topiramate, and gabapentin. Gabapentin has also shown promise in relieving many forms of neuropathic pain and is well tolerated.23 There is little or no evidence to support the use of non-antiepileptic drugs in the treatment of tic douloureux. 22

Surgical Treatment

Medical management should always precede a surgical procedure and no surgical procedure is warranted unless pharmacological therapy has failed either because of inadequate pain relief or unacceptable side effects. The three primary surgical treatments are gangliolysis, stereotactic radiosurgery, and suboccipital craniectomy with microvascular decompression (Box 48.2).

Gasserian Gangliolysis

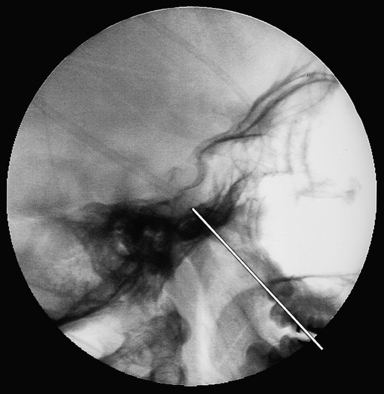

Trigeminal gangliolysis avoids the risks of a craniotomy and its objective is to destroy selectively the A-δ and C fibers (nociceptive) while preserving the A-α and β fibers (touch). It can be repeated easily if the pain recurs, and is associated with minimal rate of morbidity. In the gangliolysis procedure, the gasserian ganglion and adjacent sensory root of the trigeminal nerve are injured, with the expectation that a more permanent effect can be achieved than following a neurectomy because neural regeneration is less likely to occur in these areas than in the peripheral trigeminal branches. In the past, an anterior trigeminal rhizotomy was performed by exposing and dividing or otherwise injuring part or all of the main trigeminal sensory root adjacent to the gasserian ganglion.4,5 The radiofrequency gangliolysis procedure is performed by inserting a needle through the cheek into the third division of the trigeminal nerve at the foramen ovale, and then advancing the needle under fluoroscopic guidance into the gasserian ganglion and sensory root (Fig. 48.3).3,22,24–26 The entry point is 2.5 cm lateral to the corner of the mouth in the occlusal plane and the needle is aimed toward the intersection of the coronal plane halfway between the external auditory meatus and the lateral canthus and the sagittal plane centered at the pupil. The needle is advanced through the foramen ovale at the petrosphenoid junction and positioned at the level appropriate for the affected trigeminal branch. The third, second, and first divisions can then be stimulated in sequence by slowly advancing the needle tip. Generally, the mandibular division of the root is encountered 1 cm after penetration of the foramen ovale, V2 is located at 2 cm, and V1 is at 3 cm and at the level of the clivus. Once the needle is ideally situated, the patient is awakened and the relevant nerve root is stimulated to confirm stimulus-provoked cutaneous paresthesia in the painful trigeminal division. Contractions of the masseter and pterygoid muscles can occur at a low stimulation threshold with a medial trajectory. The patient is then reanesthetized and the neural destruction is produced by using a radiofrequency current to create a thermal lesion. Gangliolysis can also be performed under general anesthesia using a Fogarty catheter balloon to damage the ganglion mechanically, or by injecting glycerol into the cistern of the trigeminal ganglion. The goal is to produce the least neurological deficit that will control the patient’s pain.

Gangliolysis by any method produces pain relief for a longer period than by the injection or avulsion of a peripheral branch. Radiofrequency gangliolysis offers an 80% chance of 1-year pain relief and a 50% chance of 5-year success.16,27 Approximately 5% to 10% will not obtain relief initially or will have an early recurrence of pain; during the 5 years after the procedure, about 25% will experience recurrence.28,29 The complication rate of radiofrequency gangliolysis is 0.5% to 1% and can include meningitis, damage to other cranial nerves, corneal anesthesia, masseter weakness, and anesthesia dolorosa (total sensory loss). Anesthesia dolorosa is the most dreaded complication of ablative lesions of the trigeminal nerve and refers to pain in an anesthetic region. Unfortunately, no pharmacological or ablative surgical treatment is effective for this complication.22

Glycerol gangliolysis is less often performed today than the radiofrequency or balloon gangliolysis. Because the location of the glycerol cannot be precisely targeted after injection, the results are somewhat unpredictable; however, overall there is a lower incidence of sensory loss and anesthesia dolorosa than with the radiofrequency lesion. With glycerol gasserian rhizolysis, the long-term results are not quite as good: there is a 5% to 15% incidence of early failure and about a 20% to 30% incidence of later failure.27,29

In general, patients are relieved for a longer period after gangliolysis than they are by the injection of alcohol into or avulsion of a peripheral branch. Therefore, peripheral neurectomy is indicated only when gangliolysis has failed and the patient cannot or will not tolerate a suboccipital microvascular decompression. Alternatively, a local anesthetic block into the trigger area or region of pain may provide transient relief until definitive therapy can be undertaken.2,16,22

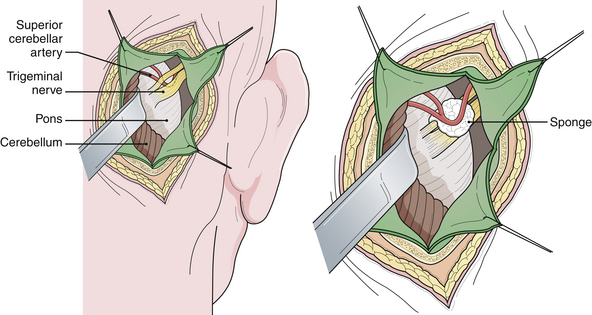

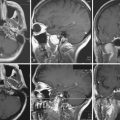

Microvascular Decompression

Vascular compression of the trigeminal nerve at its entrance into the pons is the common etiological factor in trigeminal neuralgia. Jannetta developed an operation to move the offending vessel(s) away from the nerve.30,31 This procedure is referred to as microvascular decompression because it involves an operating microscope and microsurgical technique. The area is exposed through a lateral posterior fossa craniectomy (retromastoid craniectomy), and after the vessel or vessels are separated from the nerve, a material such as a synthetic sponge or Teflon felt is inserted to maintain the separation (Fig. 48.4). The trigeminal nerve must be carefully and circumferentially inspected along its entire intracranial course from the root entry zone to its entrance laterally into Meckel’s cave. This procedure ordinarily provides pain relief without any facial sensory loss and has a greater potential for producing long-lasting pain relief. It is interesting to note that the tic pain does not always stop immediately following a microvascular decompression, but instead may take several days. Furthermore, nerve manipulation without moving the artery will transiently stop the tic pain although it will soon recur thereafter.

Review of the literature suggests that definite neurovascular compression is found in 88.6% of cases, but an average of 7.5% of explorations reveal no pathology intraoperatively.19 The results of microvascular decompression are excellent if arterial compression is identified. The superior cerebellar artery is the most common (70-80%) cause of trigeminal neuralgia. When the pain is perceived in V2 or V3 divisions, the usual finding intraoperatively is compression of the rostral and anterior portion of the nerve. The anterior inferior cerebellar artery is the compressive vessel in 10% of cases and occurs in the caudal and posterior portion of the nerve closest to nerve VI. Veins impact the nerve in 5% to 13% of cases.25 Among 68 personal patients followed for an average of 54 months, 72% had excellent pain relief and 6% had good relief that did not lead to any sensory loss.21 The initial failure rate for microvascular decompression is in the 5% to 10% range.23,28,29,32 Subsequently, the rate of pain recurrence averages about 3.5% per year. This procedure is contraindicated in patients with atypical facial pain because of the poor results achieved. Magnetic resonance angiographic imaging effectively excludes secondary causes of trigeminal neuralgia, which warrant nonmicrovascular decompression management. If no significant vascular compression is identified at operation, the main sensory root of the trigeminal nerve can be partially divided adjacent to the pons (posterior trigeminal rhizotomy). This has a similar probability of providing pain relief, but will cause some degree of facial hypoesthesia. The intrinsic somatotopic organization of the nerve tends to spare the superiorly located ophthalmic segment when performing a partial sensory rhizotomy of the lateral two thirds of the nerve.

When compared with other surgical treatments, it is widely accepted that microvascular decompression is associated with the lowest rates of recurrence and sensory loss, although more serious risks of morbidity (5%) and mortality (0.5%) are encountered than after Gamma Knife radiosurgery or gangliolysis. It has the best long-term success rate of any of the available surgical treatments. In the event of a recurrence after microvascular decompression, reexploration of the nerve can be performed, with less rewarding results, but pathological vessel impingement may not be found and a partial rhizotomy still needs to be considered.33

Stereotaxic Radiosurgery

Gamma Knife radiosurgery has been advocated as a minimally invasive alternative surgical approach to microvascular decompression or percutaneous surgeries. The short-term results are as good as gangliolysis for tic douloureux, although as is true for all other types of treatments for this disorder, atypical clinical features or a history of prior tic surgery lowers the success rate. Currently there are two types of radiosurgery technologies: linear accelerators (linacs) and Gamma Knife. A 2009 report indicates that over 2800 patients had been treated with the Gamma Knife throughout the world by 1999. From 70% to 80% of patients are pain-free in the short-term, although up to 50% relapse. Doses of 60 to 90 Gy were used in a single session and most of the patients responded to radiosurgery within 6 months of the procedure, with a median of 2 months and a low incidence of complications.34–38 These results are promising, although the recurrence rate and long-term morbidity rate remain to be seen. In another recent study of 102 patients, despite an 81% early response rate, 56% of patients who experienced initial pain relief suffered treatment failure. Side effects also include facial dysesthesias, corneal irritation, vascular damage, hearing loss, and facial weakness, varying with dose plan and target areas. Oddly, pain relief usually does not occur for 2 to 12 weeks after radiosurgery.37,38

Peripheral Neurectomy

Resection or avulsion of a branch of the trigeminal nerve has a long history in the treatment of tic douloureux, but it is rarely a procedure of choice today in countries with developed health care. It produces complete anesthesia in the distribution if the avulsed branch, which can be a significant disability for the patient.39 Pain relief rarely lasts more than a year or so, and repeating the procedure does not produce as good results as the original. However, if gangliolysis is not available or has failed in a patient who has also failed stereotactic radiosurgery, it could be considered.

Barker F., Jannetta P., Bissonette D., et al. Microvascular decompression for typical trigeminal neuralgia: a 20 year experience. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:392A.

Burchiel K., Steege T., Howe J., et al. Comparison of percutaneous radiofrequency gangliolysis and microvascular decompression for the surgical management of tic douloureux. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:111-119.

Kondziolka D., Lunsford L., Flickinger J. Stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:42-47.

Loeser J. Cranial neuralgias. In: Bonica J., editor. The Management of Pain in Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990:676-686.

Sweet W. The treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (tic douloureux). N Engl J Med. 1986;315:174-177.

Please go to expertconsult.com to view the complete list of references.

1. Gybels J., Sweet W. Neurosurgical Treatment of Persistent Pain: Physiological and Pathological Mechanisms of Human Pain. Basel: Karger; 1989.

2. Loeser J. The management of tic douloureux. Pain. 1977;3:155-162.

3. Rovitt R., Murali R., Jannetta P. Trigeminal Neuralgia. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1990.

4. Stookey B., Ransohoff J. Trigeminal Neuralgia: Its History and Treatment. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1959.

5. White J., Sweet W. Pain and the Neurosurgeon: A Forty-Year Experience. Springfield, IL: Charles C Thomas; 1969.

6. Katusic S., Williams D., Beard C., et al. Epidemiology and clinical features of idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Neuroepidemiology. 1991;10:276-281.

7. Wilkins R. Trigeminal neuralgia. In: Rengachary S.S., Wilkins R.H., editors. Principles of Neurosurgery. London: Wolfe; 1993:41-47.

8. Bullitt E., Tew J., Boyd J. Intracranial tumors in patients with facial pain. J Neurosurg. 1986;64:865-871.

9. Brisman R. Trigeminal neuralgia and multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1987;44:379-381.

10. Jensen T., Rasmussen P., Reske-Nielsen E. Association of trigeminal neuralgia with multiple sclerosis: clinical and pathological features. Acta Neurol Scand. 1982;1982:182-189.

11. Resnick D., Jannetta P., Lunsford D. Microvascular decompression for trigeminal neuralgia in patients with multiple sclerosis. Surg Neurol. 1996;46:358-362.

12. Rushton J., Olafson R. Trigeminal neuralgia associated with multiple sclerosis. Arch Neurol. 1965;13:383-386.

13. Sweet W. The treatment of trigeminal neuralgia (tic douloureux). N Engl J Med. 1986;315:174-177.

14. Tenser R. Trigeminal neuralgia: mechanisms of treatment. Neurology. 1998;51:17-19.

15. Calvin W., Loeser J., Howe J. A neurophysiological theory for the pain mechanism of tic douloureux. Pain. 1977;3:147-154.

16. Loeser J. Tic douloureux. Pain Res Manage. 2001;6:156-165.

17. International Headache Society. Classification and diagnostic criteria for headache disorders, cranial neuralgias, and facial pain. Headache classification committee of the International Headache Society. Cephalalgia. 1988;8:1-96.

18. Zakrzewska J. Diagnosis and differential diagnosis of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:14-21.

19. Patel N., Aquilina K., Clarke Y., et al. How accurate is magnetic resonance angiography in predicting neurovascular compression in patients with trigeminal neuralgia? A prospective, single-blinded comparative study. Br J Neurosurg. 2003;17:60-64.

20. Raslan A.M., DeJesus R., Berk C., et al. Sensitivity of high-resolution three-dimensional magnetic resonance angiography and three-dimensional spoiled-gradient recalled imaging in the prediction of neurovascular compression in patients with hemifacial spasm. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(4):733-736.

21. Van Kleef M., Genderen W., Narouze S., et al. Trigeminal neuralgia. Pain Pract. 2009;9:252-259.

22. Loeser J. Cranial neuralgias. In: Bonica J., editor. The Management of Pain in Clinical Practice. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lea & Febiger; 1990:676-686.

23. Cheshire W. Defining the role for gabapentin in the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. J Pain. 2002;3:137-142.

24. Nugent G. Trigeminal neuralgia: treatment by percutaneous electrocoagulation. In: Wilkins R.R., Rengachary S.S., editors. Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1985:2345-2350.

25. Piatt J.J., Wilkins R. Treatment of tic douloureux and hemifacial spasm by posterior fossa exploration: therapeutic implications of various neurovascular relationships. Neurosurgery. 1984;14:462-471.

26. Sweet W. Trigeminal neuralgia: problems as to cause and consequent conclusions regarding treatment. In: Wilkins R.R., Rengachary S.S., editors. Neurosurgery Update II: Vascular, Spinal, Pediatric, and Functional Neurosurgery. New York: McGraw-Hill, 1991.

27. Burchiel K., Steege T., Howe J., et al. Comparison of percutaneous radiofrequency gangliolysis and microvascular decompression for the surgical management of tic douloureux. Neurosurgery. 1981;9:111-119.

28. Cheng T., Cascino T., Onofrio B. Comprehensive study of diagnosis and treatment of trigeminal neuralgia secondary to tumors. Neurology. 1993;43:2298-2302.

29. Elias W., Burchiel K. Microvascular decompression. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:35-41.

30. Barker F., Jannetta P., Bissonette D., et al. Microvascular decompression for typical trigeminal neuralgia: a 20 year experience. J Neurosurg. 1994;80:392A.

31. Jannetta P. Microsurgical approach to the trigeminal nerve for tic douloureux. Prog Neurosurg. 1976;7:180-200.

32. Burchiel K., Clark H., Haglund M. Long-term efficacy of microvascular decompression in trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 1989;69:35-38.

33. Tatli M., Satici O., Kanpolat Y., Sindou M. Various surgical modalities for trigeminal neuralgia: literature study of respective long-term outcomes. Acta Neurochir (Wien). 2008;150(3):243-255.

34. Kondziolka D., Lunsford L., Flickinger J. Stereotactic radiosurgery for the treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Clin J Pain. 2002;18:42-47.

35. Maesawa S., Salame C., Flickenger J. Clinical outcomes after stereotaxic radiosurgery for idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. J Neurosurg. 2001;94:14-20.

36. Young R., Vermeulen S., Grim P. Gamma Knife radiosurgery for treatment of trigeminal neuralgia. Neurology. 1997;48:608-614.

37. Dhople A.A., Adams J.R., Maggio W.W., et al. Long-term outcomes of Gamma Knife radiosurgery for classic trigeminal neuralgia: implications of treatment and critical review of the literature. Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(2):351-358.

38. Dvorak T., Finn A., Price L.L., et al. Retreatment of trigeminal neuralgia with Gamma Knife radiosurgery: is there an appropriate cumulative dose? Clinical article. J Neurosurg. 2009;111(2):359-364.

39. Cetas J.S., Saedi T., Burchiel K.J. Destructive procedures for the treatment of nonmalignant pain: a structured literature review. J Neurosurg. 2008;109(3):389-404.