Chapter 276 Trichomoniasis (Trichomonas vaginalis)

Pathogenesis

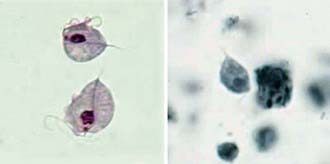

T. vaginalis is an anaerobic, flagellated protozoan parasite. Infected vaginal secretions contain 101 to 105 or more protozoa/mL. T. vaginalis is pear shaped and exhibits characteristic twitching motility in wet mount (Fig. 276-1). Reproduction is by binary fission. It exists only as vegetative cells; cyst forms have not been described. T. vaginalis damages host cells and tissues by a number of mechanisms. Adhesion molecules allow attachment of T. vaginalis to host cells, and hydrolases, proteases, and cytotoxic molecules act to destroy or impair the integrity of host cells. Parasite-specific antibodies and lymphocyte priming occur in response to infection, but durable protective immunity does not occur.

Figure 276-1 Trichomonas vaginalis trophozoites stained with Giemsa (left) and iron hematoxylin (right).

(From the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Laboratory identification of parasites of public health concern. Trichomoniasis (website). www.dpd.cdc.gov/dpdx/HTML/ImageLibrary/Trichomoniasis_il.htm. Accessed August 30, 2010.)

Clinical Manifestations

The incubation period in females is 5-28 days. Symptoms may begin or exacerbate with menses. Most infected women eventually develop symptoms, although up to one third remain asymptomatic. Common signs and symptoms include a copious malodorous gray, frothy vaginal discharge, vulvovaginal irritation, dysuria, and dyspareunia. Physical examination may reveal a frothy discharge with vaginal erythema and cervical hemorrhages (“strawberry cervix”). The discharge usually has a pH of >4.5. Abdominal discomfort is unusual and should prompt evaluation for pelvic inflammatory disease (Chapter 114).

Prevention

Prevention of T. vaginalis infection is best accomplished by treatment of all sexual partners of an infected person and by programs aimed at prevention of all sexually transmitted infections (Chapter 114). No vaccine is available, and drug prophylaxis is not recommended.

Bravo AB, Miranda LS, Lima OF, et al. Validation of an immunologic diagnostic kit for infectious vaginitis by Trichomonas vaginalis, Candida spp., and Gardnerella vaginalis. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis. 2009;63:257-260.

Forna F, Gülmezoglu AM: Interventions for treating trichomoniasis in women. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2:CD000218, 2003.

Johnston VJ, Mabey DC. Global epidemiology and control of Trichomonas vaginalis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2008;21:56-64.

Kissinger P, Amedee A, Clark RA, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis treatment reduces vaginal HIV-1 shedding. Sex Transm Dis. 2009;36:11-16.

Lowe NK, Neal JL, Ryan-Wenger NA. Accuracy of the clinical diagnosis of vaginitis compared with a DNA probe laboratory standard. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;113:89-95.

Nye MB, Schwebke JR, Body BA. Comparison of APTIMA Trichomonas vaginalis transcription-mediated amplification to wet mount microscopy, culture, and polymerase chain reaction for diagnosis of trichomoniasis in men and women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2009;200:188.e1-188.e7.

Shafir SC, Sorvillo FJ, Smith L. Current issues and considerations regarding trichomoniasis and human immunodeficiency virus in African-Americans. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2009;22:37-45.

Van Der Pol B, Kwok C, Pierre-Louis B, et al. Trichomonas vaginalis infection and human immunodeficiency virus acquisition in African women. J Infect Dis. 2008;197:548-554.

Wendel KA, Workowski KA. Trichomoniasis: challenges to appropriate management. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44:S123-S129.