7 Trichloroacetic Acid (TCA) Peels

Introduction

Chemical peels have been documented in American medical literature since Eller and Wolff described their use for treatment of blemishes and pitted scars of the face in 1941. Since that time, physicians have expanded the indications for chemical peels and advanced the understanding of the physiologic effect of these agents. Chemical peels are now commonly used to remove damaged skin and to promote regeneration and improvement in quality and overall texture of the skin. Chemical peels are classified according to their depth of penetration. Superficial peels are those reaching, at greatest depth, the superficial papillary dermis. Medium-depth peels are those reaching the papillary to reticular dermis, and deep peels extending to the mid-reticular dermis. Trichloroacetic acid (TCA) may be used for tissue penetration of superficial and medium-depths, depending on the concentration (Table 7.1). For superficial peels, TCA should be between 10% and 25% concentration. For medium-depth peels, most experienced physicians will use a concentration of 35% combined with another agent, and no greater than 40% since concentrations of 50% are known to impart a much greater risk of scarring, pigment dyschromia and undesired textural change. See Box 7.1.

| Peel type | Agent |

|---|---|

| Superficial | TCA 10–25% Jessner’s solution Glycolic acid |

| Medium | TCA 35–50% Solid CO2 + TCA 35% Glycolic acid 70% + TCA 35% Jessner’s solution + TCA 35% |

| Deep | Phenol peel |

Selection of Peel Type

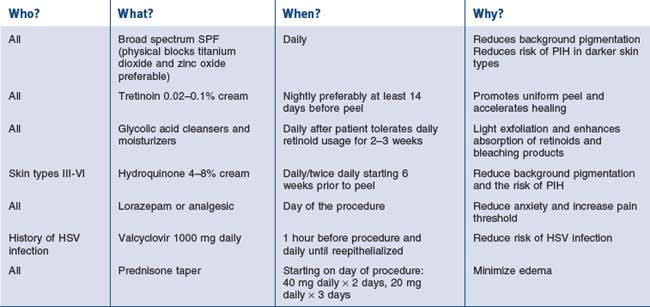

Choosing the correct concentration for the desired indication in any one patient requires consideration of the following factors: what is desired by the patient, photoaging classification by the physician, Fitzpatrick sun-reactive skin type classification, sebaceous quality of the skin, presence of inflammation (seborrhea, retinoid dermatitis, etc.), and skin translucency. (The more translucent the skin and more inflammation present, the more likely the patient will convert from a superficial to a medium-depth peel.) Indications for superficial peels include treatment of melasma, comedonal acne, and improvement of overall skin reflectiveness, texture, and tone. The use of superficial peels for actinic damage is controversial and some studies suggest that the improvement of actinic damage using superficial peels is no greater than that achieved by using topical glycolic products or topical retinoids alone. Indications for a medium-depth peel include reversal of actinic damage, including removal of actinic keratoses and other epidermal lesions, reduction of rhytides, removal of dyschromia, and improvement of atrophic scarring (Figs 7.1 and 7.2).

• Superficial peels

For superficial peels, patients who belong to Glogau classification for photoaging types I and II are most appropriate (Box 7.2). Severe photodamage with resultant hyperkeratosis and parakeratosis creates a barrier to peel penetration and will minimize the effect of any peeling agent. This can make using only a superficial peeling agent almost totally ineffective. It is therefore recommended that a retinoid be used to pretreat the area and increase the penetration of the peel. With regards to sun-reactive skin types, Fitzpatrick types IV, V, and VI are most prone to developing postinflammatory hyperpigmentation (Table 7.2). Pretreatment with tretinoin and hydroquinone may minimize this effect and can be particularly helpful in type IV, where the hyperpigmentation may be the most noticeable compared to their normal skin tone. Topical ascorbic acid has also been used as a priming agent and has been found to be beneficial in decreasing pigmentation. Soliman et al (2007) reported a significant improvement in melasma patients who were pretreated with topical 5% ascorbic acid prior to a superficial peel with 20% TCA. With adequate patient education, patients with darker complexions can safely undergo superficial peels without risk of permanent color change as hyperpigmentation fades over time and with treatment. Oily, thickened, sebaceous skin may lead to uneven and less effective superficial peeling. Peel response may be improved with the use of pretreatment tretinoin on a daily basis combined with alpha-hydroxy acids (10–20%) used as a daily cream, lotion or gel. In addition, a more vigorous skin preparation may be used to enhance peel absorption. In contrast, there are patients, usually women, who have paper-thin skin with a translucent quality. These patients are at an increased risk for conversion to a medium-depth peel with superficial peeling agents and should have their skin preparation and skin pretreatment performed cautiously. Other patients who deserve caution are those with seborrhea and other types of dermatitis (retinoid, etc.) Inflammation in the skin is known to enhance uptake of the peel solution and result in a deeper than expected peel.

Box 7.2

Glogau’s classification of photoaging

Based on Glogau (1994)

Table 7.2 Fitzpatrick’s classification of sun-reactive skin types

| Skin type | Color | Reaction to first summer exposure |

|---|---|---|

| I | White | Always burn, never tan |

| II | White | Usually burn, tan with difficulty |

| III | White | Sometimes mild burn, tan average |

| IV | Moderate brown | Rarely burn, tan with ease |

| V | Dark brown* | Very rarely burn, tan very easily |

| VI | Black | No burn, tan very easily |

* Asian Indian, Oriental, Hispanic, or light African descent, for example

• Contraindications

In addition to choosing the right patient with reasonable expectations for the procedure, complications may be avoided by excluding patients under certain circumstances. Relative contraindications for chemical peels include the use of isotretinoin (should be off it for at least 6–12 months), a history of radiation to the region (ablating adnexal structures), active herpes simplex or bacterial infection, history of hypertrophic scar formation, and a rhytidectomy or brow lift in the previous 3 months. With regards to brow lift and rhytidectomy, while waiting 3 months for resurfacing has traditionally been recommended, a publication by Alster et al (2004) described 34 patients who underwent combination carbon dioxide (CO2) or erbium:yttrium-aluminum-garnet (Er:YAG) laser skin resurfacing and surgical lifting procedures (S-lift rhytidectomy, blepharoplasty, and brow lift). The effects were found to be no different than those in patients undergoing the laser-only procedure. An article by Herbig et al (2009) suggests that the same may be true for chemical peel resurfacing. They reported performing 27 face and/or neck lifts with SMAS plication or SMAS-ectomy along with full face chemical peels and noted no hypertrophic scarring. Certain facial surgical procedures utilizing a skin or muscle flap may still compromise vascular supply to the tissue and result in delayed healing following medium-depth peels. Patients with a history of herpes simplex virus infection should be pretreated with an oral antiviral agent, which is continued until reepithelialization occurs.

Superficial TCA Peels

• Skin preparation and application

When applying the peeling agent, as in the skin prepping, it is helpful to divide the area to be peeled into units with one gauze used per unit. This will help quantify the amount of peel used per unit. A 2″ × 2″ gauze is submerged and wrung out (small metal cups may be used to contain the peel agent being used, as other materials will corrode over time) and with a wiping or scrubbing motion (depending on the patient) the peel is performed. All variables should be documented in the chart including the type of prep, time of prep, peel agent, unit areas (number and type of applicators), pressure of application (scrub vs wipe). It is often useful to have the patient keep a log of their peeling so as to help guide the physician in planning their next peel. The patient should record the type of flakes (small white, large brown), the areas of peeling and the extent of peeling. In addition, if a less than expected or deeper than expected peel occurs, documentation is clear on how the peel was performed. The end point of a superficial peel with TCA is speckled white frost. Once this is noted, cool water gauze compresses are placed over the areas peeled for patient comfort. The cool water compresses are used for symptomatic relief and to eliminate any possible pooling from the solution. Once the peel solution is applied, absorption occurs and cannot be neutralized by additional base application. After a few minutes, the patient may rinse off the area peeled with cool water splashes until tingling or burning subsides (Table 7.3).

| Vigorous ‘scrub’ | Light ‘wipe’ |

|---|---|

| Sebaceous skin | Acne |

| Advanced photoaging | Seborrhea |

| Translucent or sensitive skin |

• Postpeel advice to patients

Patients should be instructed that the skin may be pink initially, feel tight, peel in 2 to 3 days and continue peeling for up to 1 week. It should also be clear that no scrubbing is to be performed at home, and the patient must resist the urge to pick, peel or scratch. They may resume moisturizer use after 4 hours, after soaks, and as needed. In previous studies, occlusion with ointment vehicle was shown to enhance medium-depth peel necrosis when applied after 4 hours rather than immediately after application of the peel. Swelling can be improved by sleeping with the head elevated and using cool compresses for 15–30 minutes several times daily. Direct sunlight should be avoided for at least 3 weeks after the peel. Patients should resume their prepeel regimen of a retinoid and alpha-hydroxy acid lotion when their skin is healed, which is usually by 5 to 7 days postpeel. Alpha-hydroxy acids are typically dispensed starting at a lower concentration (8%), with a gradual increase in concentration, depending on the patient’s tolerance, up to 20% lotion. When indicated, as in the treatment of melasma or in the prophylaxis of those at risk for postinflammatory hyperpigmentation, hydroquinone may also be started at that time (Table 7.4).

Medium-Depth TCA Peels

As in the superficial peel, medium-depth peel solution is compounded using a weight/volume method. A concentration of 35% should be prepared as described above (see Making up the solution). Combination peels are those using solid CO2 ice plus 35% TCA (Brody combination), Jessner’s solution plus 35% TCA (Monheit combination), or 70% glycolic acid and 35% TCA (Coleman combination). These peels will be discussed in greater detail later.

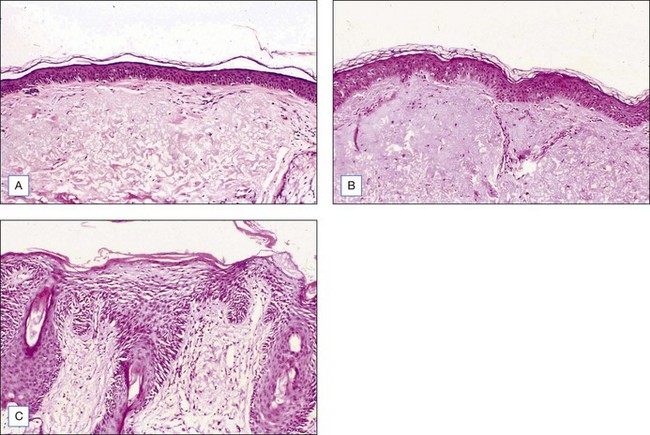

• Jessner’s solution and 35% TCA (Monheit combination)

After preparation, Jessner’s solution is applied to each of the facial units with a 2″ × 2″ gauze for each unit. One or two coats may be used to create an endpoint of a speckled white frost and mild, uniform erythema (Fig. 7.3A). If necessary, a Wood’s lamp may be used to verify even application as the salicylic acid component in Jessner’s peel solution is fluorescent under the Wood’s lamp. Even application is important as it will affect the uptake of the TCA peel solution to follow. After the Jessner’s peel, cool water compresses may be placed to provide symptomatic treatment of mild burning and heat. It is recommended to wait at least 5 minutes before application of TCA following Jessner’s peel preparation.

• Glycolic acid 70% gel and 35–40% TCA (Cook total body peel)

This peel combination has been used to treat nonfacial skin. It has been reported by Cook et al (2001) to be effective in the treatment of the neck, chest, arms, hands, legs, back, abdomen and balding scalp. In our practice we use this method to treat photodamaged arms (i.e., lentigos, actinic keratoses and solar purpura). When performing this combination, it is important to use glycolic acid 70% gel rather than solution. The glycolic gel acts as a barrier when combined with the TCA in order to prevent excessive penetration and potential scarring.

• 35% TCA peel

After the face is completely dry, 35% TCA is used to perform the medium-depth peel. It is helpful to use a small container to dip cotton tips or gauze into for better control of the amount of solution. Again, the face is broken into units and TCA is painted evenly using unidirectional strokes. Either cotton tips or 2″ × 2″ gauze may be used. Excess peel solution should be gently wrung from the cotton against the side of the container to avoid dripping of solution into the eyes or onto the neck. Typically, the units are the forehead (sometimes subdivided into 2–4 units depending on the size), the cheeks and temples (each getting one 2″ × 2″ gauze), the chin, the upper lip, and nose. After application, contiguous white frost begins to appear within 30 seconds and matures over 2 to 3 minutes. The degree of frost should be evaluated and documented after this time elapse (Table 7.5). Level II frosting is desired for most medium-depth peels and is characterized by an even, white-coated frost with background erythema (Fig. 7.3B). It is important to treat cautiously areas prone to scar, such as the zygomatic arch, bony prominences of the jaw, and the chin. In addition, the eyelids should be treated cautiously and achieve at most, a level II frost. Level III frost may be appropriate for thickened, keratotic lesions, heavy actinic damage or significantly thickened skin. Skip areas may be retreated lightly after evaluating initial frost. Thickened actinic keratoses or epidermal lesions will not take peel solution evenly and often need cotton-tipped reapplication with vigorous rubbing for peel penetration. Feathering is important around the brows, into the hairline, around the neck and onto the vermilion border to minimize lines of demarcation of peeled and nonpeeled areas. As frost develops, cool, wet compresses should be placed over all areas peeled.

| Level of frost | Peel type | Clinical response |

|---|---|---|

| I | Superficial | Speckled white Mild erythema |

| II | Medium | Even white coat Background erythema |

| III | Medium/deep | Solid white, opaque No background erythema Penetration into reticular dermis |

Patients may expect the skin to feel tight with swelling, particularly around the eyes. We have found that with prednisone prescribed as described above, this is greatly reduced. Aquaphor is reapplied frequently over the 4 days following the peel and serves to promote faster reepithelialization. After 24 hours, the patient may shower. The face may be cleaned twice daily with a gentle cleanser. As the epidermis separates, the tight, dry, ‘cracked pottery’ appearance gives way to peeling and serous exudates with crusting may occur. Patients are instructed not to pick or peel the skin, though careful trimming with clean, sharp scissors is allowed. Reepithelialization typically begins on the 3rd day and continues up to 10 days postpeel. On the 5th day, a moisturizing cream may be applied to any dry areas as needed. After the skin has healed (sometimes this takes up to 10 days), a green toner may be applied to cover the new, slightly erythematous skin, with make-up over this toner. Redness fades to pink over the course of the 1st week and will gradually continue to fade to complete resolution over the course of 2 to 3 weeks. In rare cases, erythema may last up to 4 months and may be accompanied by pruritus, burning, stinging, and a change in skin texture, in which case potential etiologies, including rosacea, systemic lupus erythematosus, atopy, eczema, allergic or irritant contact dermatitis (retinoid, glycolic acid or other), should be considered. This may be treated with mild topical steroids such as desonide cream or westcort ointment depending on the intensity of erythema, up to 3 × daily, with weaning over 2 to 3 weeks as symptoms resolve. It is recommended that patients avoid direct sunlight and wind with sun exposure for 6 to 8 weeks after peeling to help prevent postinflammatory hyperpigmentation. In addition, a sunscreen with both UVA and UVB coverage should be applied daily (Fig. 7.4).

Alster TS, West TB. Effect of pretreatment on the incidence of hyperpigmentation following cutaneous CO2 laser resurfacing. Dermatologic Surgery. 1999;25:15-17.

Alster TS, Doshi SN, Hopping SB. Combination surgical lifting with ablative laser skin resurfacing of facial skin: a retrospective analysis. Dermatologic Surgery. 2004;30:1191-1195.

Beeson WM, Rachel JD. Valcyclovir prophylaxis for herpes simplex virus infection or infection resuming following laser resurfacing. Dermatologic Surgery. 2002;28:431-436.

Brody HJ. Complications of chemical resurfacing. Dermatologic Clinics. 2001;19:427-437.

Coleman WPIII, Futrell JM. The glycolic acid trichloroacetic acid peel. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1994;20:76-80.

Cook KK, Cook WR. Chemical peel of nonfacial skin using glycolic acid gel augmented with TCA and neutralized based on visual staging. Dermatologic Surgery. 2001;26(11):994-999.

Garg VK, Sarkar R, Agarwal R. Comparative evaluation of beneficiary effects of primary agents (2% hydroquinone and 0.025% retinoic acid) in the treatment of melasma with glycolic acid peels. Dermatologic Surgery. 2008;34:1032-1039.

Glogau RG. Chemical peeling and aging skin. Journal of Geriatric Dermatology. 1994;2(1):30-35.

Glogau RG, Matarasso SL. Chemical peels. Dermatologic Clinics. 1995;13:263-276.

Herbig K, Trussler AP, Khosla RK, Rohrich RJ. Combination Jessner’s solution and trichloroacetic acid chemical peel: technique and outcomes. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2009;124:955-964.

Hevia O, Nemeth AJ, Taylor R. Tretinoin accelerates healing after trichloroacetic acid chemical peel. Archives of Dermatology. 1991;127:678-682.

Koppel RA, Coleman KM, Coleman WPIII. The efficacy of EMLA versus ELA-Max for pain relief in medium-depth chemical peeling: a clinical and histopathologic evaluation. Dermatologic Surgery. 2000;26:61-64.

Landau M. Chemical peels. Clinics in Dermatology. 2008;26:200-208.

Lawrence N, Coleman WPIII. Superficial chemical peeling. (eds). In: Coleman WPIII, Lawrence N, editors. Skin resurfacing. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:45-56.

Lawrence N, Cox SE, Cockerell CJ, et al. A comparison of the efficacy and safety of Jessner’s solution and 35% trichloroacetic acid versus 5% fluorouracil in the treatment of widespread facial actinic keratoses. Archives of Dermatology. 1995;131:176-181.

Maloney BP, Millman B, Monheit G, et al. The etiology of prolonged erythema after chemical peel. Dermatologic Surgery. 1998;24:337-341.

Monheit GD. The Jessner’s-Trichloroacetic acid peel: an enhanced medium-depth chemical peel. Dermatologic Clinics. 1995;13:277-283.

Monheit GD. Medium depth chemical peeling. In: Coleman WPIII, Lawrence N, editors. Skin Resurfacing. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1998:57-70.

Monheit GD. Medium-depth chemical peels. Dermatology Clinics. 2001;19:413-425.

Peikert JM, Valda NK, Zachary CB. A reevaluation of the effect of occlusion on the trichloroacetic acid peel. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1994;20:660-665.

Peikert JM, Krywonis NA, Rest EB, et al. The efficacy of various degreasing agents used in trichloroacetic acid peels. Journal of Dermatologic Surgery and Oncology. 1994;20:724-728.

Rubin MG. Trichloroacetic acid peels. In: Rubin MG, editor. Manual of chemical peels. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1995:118-119.

Soliman MM, Ramadan SA, Bassiouny DA, Abdelmalek M. Combined trichloroacetic acid peel and topical ascorbic acid versus trichloroacetic acid peel alone in the treatment of melasma: a comparative study. Journal of Cosmetic Dermatology. 2007;6:89-94.

Tung RC, Bergfeld WF, Vidimos AT, Remzi BK. Alpha hydroxyl acid-based cosmetic procedures. American Journal of Clinical Dermatology. 2000;1(2):81-88.

Witheiler DD, Lawrence N, Cox SE, et al. Long-term efficacy and safety of Jessner’s solution and 35% trichloroacetic acid vs 5% fluorouracil in the treatment of widespread facial actinic keratoses. Dermatologic Surgery. 1997;23:191-196.