CHAPTER 9 TRIAGE

Triage is the process of prioritizing patient care based on patient need and available resources. In daily practice, triage decisions link individual patients with resources appropriate for their injuries, with the goal being “the greatest good for the patient.” In the setting of ubiquitous resources, these are “life or life” decisions. Triage occurs at each level along the pathway of care, from prehospital and emergency room; through the operating room, intensive care unit, and ward; to discharge and rehabilitation.

FIELD TRIAGE

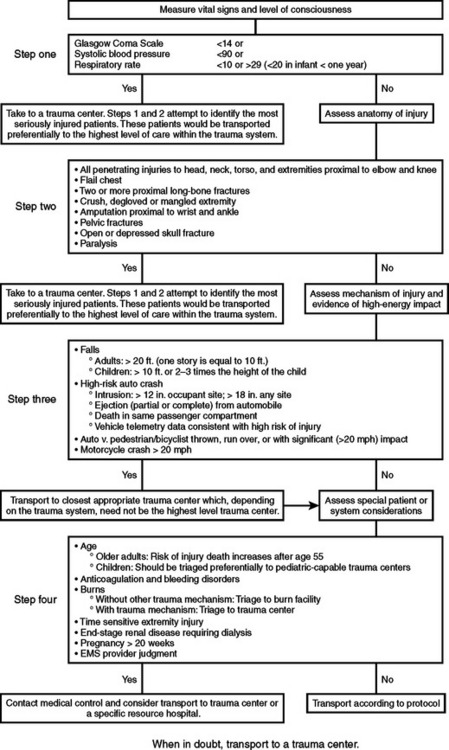

Field triage identifies severely injured trauma patients at the point of injury in the “field” and triggers a decision to transport severely injured patients to a hospital that has resources commensurate with patient needs. A common field triage decision scheme assesses the injured patient in four steps, each step linked to a determination about patient need for a level of care at a trauma center. The field triage decision scheme presented here (Figure 1), originally developed by the American College of Surgeons Committee on Trauma, was revised through an evidence-based review by an expert panel representing emergency medical services, emergency medicine, trauma surgery, and public health. The panel was convened by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), with support from the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). Its contents are those of the expert panel and do not necessarily represent the official views of CDC and NHTSA.

The field triage decision scheme emphasizes the importance of explicitly defining the capabilities of facilities within the system of care and matching the patient to the facility with the most appropriate level of care. An inclusive trauma system brings all local prehospital agencies and acute care facilities together as a network for the focused application of system capabilities to the care of each acutely injured patient. The idea is to get the right patient to the right place within the right time. Underestimation of patient injuries can lead to undertriage to facilities without adequate resources for patient needs, and overestimation of patient injuries can lead to overtriage to facilities with resources far greater than patient needs. Effective triage requires an integrated and defined shared mental model of triage across all settings of care.

MASS CASUALTY TRIAGE

Mass casualty incidents are distinguished from multiple casualty situations by available resources: with mass casualties, resources for each patient are limited, whereas with multiple casualties, full resources can be brought to bear on each individual patient. Mass casualty triage begins with recognition that an event has occurred that has generated casualties exceeding available resources.

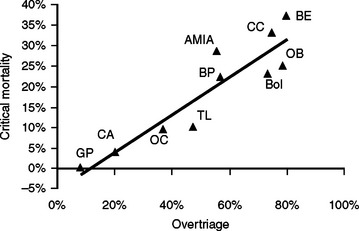

Sequential triage as casualties move along the care pathway creates an efficient, error-tolerant system that minimizes the consequences of persistent undertriage and overtriage. Overtriage keeps “distracting” casualties within the care pathway and increases the critical mortality rate, a more appropriate measure of casualty population outcome than overall mortality (Figure 2). Adequate documentation is essential for casualty tracking and re-triage. As patients move across care levels, pertinent documentation provides the developing story to the next caregivers in line.

American College of Surgeons. Resources for the Optimal Care of the Injured Patient. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 1999.

Frykberg ER. Triage: principles and practice. Scan J Surg. 2005;94:272-278.

Institute of Medicine: The Future of Emergency Care in the United States Health Care System Report Brief. Washington, DC, Institute of Medicine, 2006, www.iom.edu

MacKersie RC. History of trauma field triage development and the American College of Surgeons Criteria. Prehosp Emerg Care. 2006;10(3):287-294.