35 Tremors

Physiologic Tremor

This is normally present in healthy individuals and is related to a number of factors. Physiologic tremor typically has an 8- to 12-Hz frequency in young adults and decreases to 6–7 Hz in the senior population (Table 35-1).

| Frequency Range, Hz | Tremor Type |

|---|---|

| 1–5 | Holmes cerebellar tremor |

| 2–10 | Multiple sclerosis |

| 2–12 | Drug-induced tremor |

| 2–12 | Neuropathic tremor |

| 3–10 | Parkinsonian tremor |

| 3–10 | Task- and position-specific tremor |

| 3–12 | Dystonic tremor |

| 4–10 | Psychogenic tremor |

| 4–8 | Essential tremor |

| 7–12 | Physiologic and enhanced physiologic tremor |

| 16–25 | Orthostatic tremor |

Adapted from Bain PG. The management of tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72(Suppl. 1):i3-i16.

Pathophysiology

The etiology of many tremors is unknown. Although Parkinson disease (PD) lesions predominate in the substantia nigra, experimental animal lesions within the substantia nigra do not cause tremor, and not all patients with lesions at this level have a tremor. Moreover, a tremor develops in only half of patients poisoned with the analog of meperidine (MPTP) that preferentially destroys part of the substantia nigra and classically leads to a mimic of PD. However, even with MPTP, the tremors are not the typical resting pill rolling ones of PD tremor; these have more of an action or postural component. In contrast, ventromedial tegmentum lesions made in a monkey midbrain do produce a resting-type tremor. Pathologic tremors such as ET, dystonic tremor, and the PD tremors are thought to have multiple central generators, resulting in variable frequencies of approximately 1–26 Hz (see Table 35-1).

Pathologic Tremor

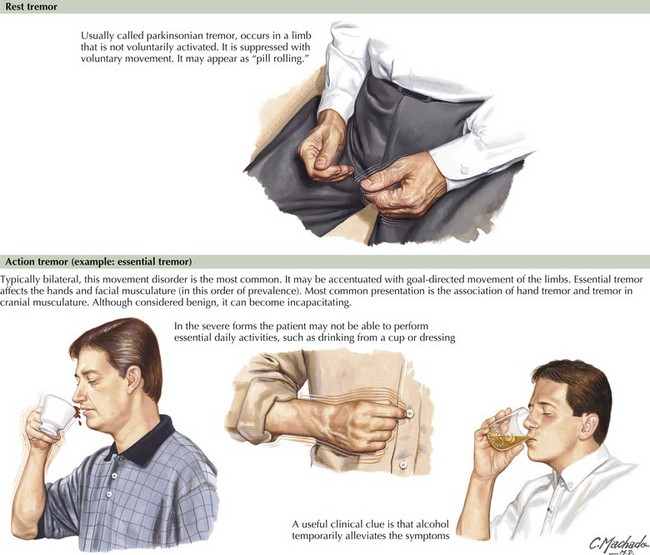

The most useful classification of pathologic tremors is based on their clinical features, especially anatomic distribution (proximal or distal, body part involved), symmetry, and the conditions that best activate them (Table 35-2). Rest tremors occur when a body part is completely supported against gravity (Fig. 35-1). Action tremors occurring during voluntary muscular contraction are further classified as (1) postural (occur in a body part maintained in position against gravity), (2) kinetic (occur during voluntary movement), or (3) isometric (occur within a muscle contracting against a stationary object).

| Type of Tremor | Clinical Features | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Postural | A posture is maintained against gravity |

Essential Tremor

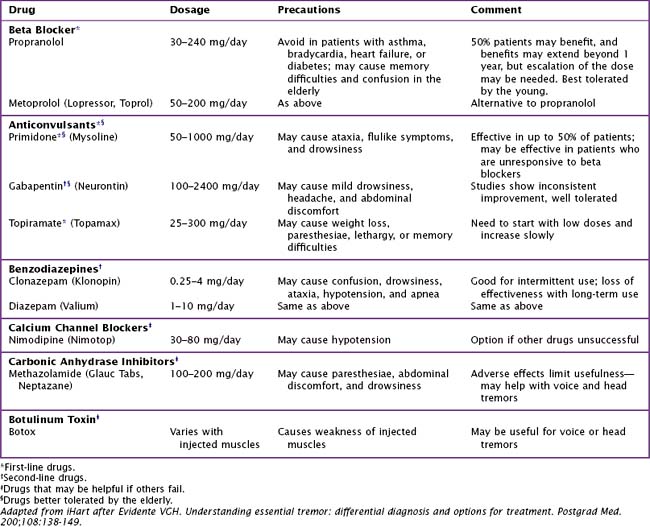

Treatment is not indicated for mild tremors that do not interfere with patients’ quality of life. However, when the ET begins to interfere with the patient’s daily activities, various therapeutic options are available. Although most patients experience a reasonable response to beta adrenergic antagonists, such as propranolol, its side effects of bronchospasm, impotence, and sleep alterations are sometimes limiting. Other beta blockers may have a lower incidence of such side effects. The majority of ET patients experience a dramatic reduction in tremor after alcohol intake. Sometimes this response is helpful in making a differential diagnosis between ET and some variants of PD. Alcohol reduces the cerebellar overactivity that is demonstrated on PET scans of ET patients. However, over time, increasing amounts of alcohol are needed to produce this effect. Alcoholism is a potential outcome. Occasionally, treatment of ET can be very frustrating (Table 35-3). In the rare instance when the patient is very significantly incapacitated, surgical intervention (thalamotomy and deep brain stimulation) is effective.

Resting Tremor

PD and sometimes its variant are typified by a resting tremor (Chapters 33 and 34). The classic “pill-rolling” PD tremor has both a flexion–extension, abduction–adduction, of the fingers or hand and a pronation–supination component of the hand and forearm. This is typically unilateral at its first appearance and may remain asymmetric for a significant time. It is slowly progressive. Although this primarily affects the hand, it sometimes can include the feet, mandible, and lips. This PD tremor is somewhat suppressed by anticholinergic drugs and, less consistently but occasionally impressively so, by levodopa and other dopamine agonist drugs. On occasion, one sees patients with monosymptomatic resting tremors unassociated with other parkinsonian features. In contrast to PD per se, these isolated tremors are often refractory to treatment; however, sometimes other features of PD do respond to treatment eventually a number of years later.

With the increased understanding of the pathogenesis and treatment of PD, many patients mistakenly assume that most tremors are related to it. The physician must be able to differentiate the more common, postural ET from the serious resting tremor of PD (Table 35-4).

| Characteristic | Essential Tremor | Parkinson Tremor |

|---|---|---|

| Type | Action/postural | Resting, “pill rolling” |

| Frequency | 4–10 Hz | 3–5 Hz |

| Age at onset | All ages | Middle age or elderly |

| Family history | First-degree relative often | None affected |

| Body part | Hands, head, voice | Hands, legs |

| Symmetry | Usually symmetric onset | Asymmetric onset, slowly |

| Course | Stable or slowly progressive | Progressive proximal as it generalizes to both sides |

| Other symptoms | Usually monosymptomatic | Rigidity, bradykinesia, flexed posture, balance problems |

| Origin | Olivocerebellar and other midbrain circuitry | Multiple generators within corticobasal ganglia and corticocerebellar circuitry |

| Other | Often transmitted as autosomal dominant, classically diminished by alcohol | May exhibit many types of tremors, including a postural one at the wrist at 5–8 Hz that may be difficult to distinguish from an essential tremor |

Orthostatic and Action Tremor

Clinical Vignette

Various medications were tried, including primidone, but no effective remedies were found.

The differential diagnosis of OT is a very limited one; the possibilities include aqueduct stenosis, pontine lesions, head trauma, and chronic inflammatory demyelinating neuropathy (CIDP). Brain MRI is important to exclude most of these. If this is normal, an EMG is indicated to exclude CIDP. Treatment is frequently problematic. Gabapentin may be helpful for OT. Treatment with topiramate, benzodiazepines, or valproic acid is sometimes of limited help. The nature of OT is commonly poorly understood by family and friends. They may need reassurance as to the nonpsychiatric nature of the patient’s symptoms especially when he or she appears so normal in all other aspects. Patient anxiety is often a result; it may also require treatment (Table 35-5).

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Isolated chin tremors | Familial syndrome with onset in infancy or childhood; often intermittent and stress-induced |

| Dystonic tremor | A postural or kinetic tremor in an extremity or body part by dystonia; may at times be more obvious than the dystonic movement it accompanies. |

| Isolated voice tremor | May be a variant of essential tremor or dystonic tremor accompanying focal dystonia of the vocal cords (spasmodic dystonia) |

| Alcohol withdrawal tremor | An action/postural tremor is a prominent feature of the alcohol withdrawal syndrome; after recovery from the withdrawal state, some individuals have a persistent essential-type tremor; withdrawal of other sedative-type drugs (barbiturates, benzodiazepines) after prolonged use may also produce the same type of tremor |

| Task-specific tremors | May occur primarily during the performance of specific tasks or postures; primary writing tremor is the most common, but similar task-specific tremors have been described in typists, musicians, and sportsmen |

| Neuropathic tremor | Irregular, asymmetric, usually distal tremor, with frequencies of 3–12 Hz; may occur at rest, with posture with movement, and is associated with peripheral nerve disease; usually subsides with successful treatment of the underlying neuropathy or with beta blockers |

Drug-Induced (Iatrogenic) Tremor

A parkinsonian-like resting tremor may occur after ingestion of neuroleptic, antidopaminergic drugs (including dopamine-depleting drugs). Unlike the tremor of PD, the resting, pharmacologically induced tremor is initially bilateral and symmetric. An intention tremor may occur with lithium intoxication or chronic alcoholism. A tardive tremor is associated with long-term neuroleptic use. The anticonvulsants phenytoin and sodium valproate can cause various action tremors. An action tremor resembling an enhanced physiologic tremor is also produced by medications such as calcium channel blockers, amiodarone, theophylline, adrenaline, amphetamine, lithium, caffeine, cocaine, marijuana, and drug or alcohol withdrawal (Table 35-6).

| Drug | Type of Tremor |

|---|---|

| Alcohol withdrawal | Postural, intention |

| Drug withdrawal | Postural |

| Insulin (by inducing hypoglycemia) | Postural |

| CNS acting | |

Bain PG. The management of tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg, Psychiatry. 2002;72(Suppl. 1):i3-i16.

Rodrigues JP, Edwards DJ, Walters SE, et al. Blinded placebo crossover study of gabapentin in primary orthostatic tremor. Mov Disord. 2006 Jul;21(7):900-905.

Roze E, Coêlho-Braga MC, Gayraud D, et al. Head tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2006 Aug;21(8):1245-1248.

Stoessl AJ. Radionuclide scanning to diagnose Parkinson disease: is it cost-effective?. Nat Clin Pract Neurol. 2009 Jan;5(1):10-11. Epub 2008 Dec 9. A recent study concluded that 123I-2β-carbomethoxy-3β-(4-iodophenyl)-n-(3-fluoropropyl)nortropane single-photon emission computed tomography (123I-FP-CIT SPECT) is helpful when there is difficulty making the differential diagnosis between essential tremor and Parkinson’s disease

Tan EK, Lee SS, Fook-Chong S, et al. Evidence of increased odds of essential tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Mov Disord. 2008;23:993-997.

Zesiewicz TA, Hauser RA. Phenomenology and treatment of tremor disorders. Neurol Clin. 2001;19:651-680.