CHAPTER 33 TREMOR

Tremor is the most common movement disorder encountered in clinical neurology. It denotes a rhythmic involuntary movement of one or several regions of the body.1 Although most tremors are pathological, a low-amplitude physiological action tremor can also be detected in healthy subjects and may even be of functional relevance for normal motor control.2 Pathological tremor is visible to the naked eye and mostly interferes with normal motor function. The disabilities caused by these tremors are as diverse as their clinical appearance, pathophysiology, and etiologies. Although there are numerous medical treatment options, their efficacy is limited, and therefore refined stereotactic surgical approaches have become increasingly important. Here, we provide some general clinical definitions and then describe all these aspects for each of the most important pathological tremor syndromes separately.

CLINICAL DEFINITIONS

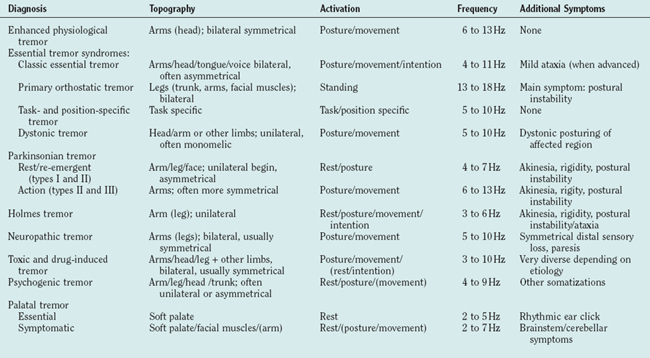

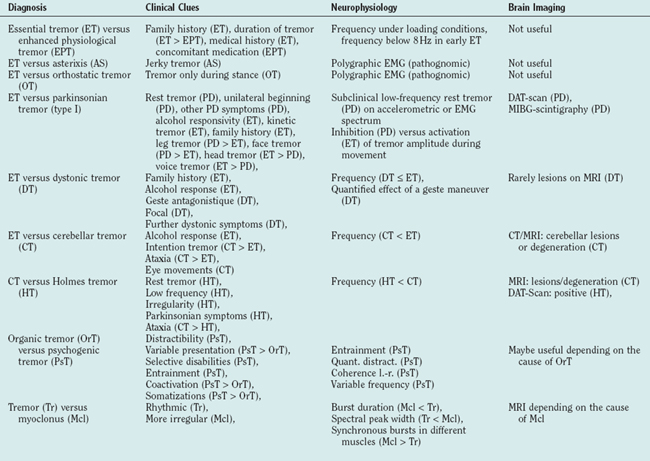

The clinical examination of tremor patients should focus on certain aspects of the tremor that form the basis for the differential diagnosis (Tables 33-1 and 33-2) and should always be documented:

ENHANCED PHYSIOLOGICAL TREMOR

Normal physiological tremor is an action tremor and usually not visible. It can only be measured with sensitive accelerometers. An increase of the amplitude leads to enhanced physiological tremor (EPT). The pathological tremor amplitudes are typically short lived and reversible once the cause (see Etiology) is removed. Other neurological symptoms or diseases that could cause tremor must be excluded.1

Epidemiology

There are no studies available on the epidemiology of EPT as a whole. The short-lived transient form is very likely the most common form of tremor; most people have experienced this on stressful or frightening occasions. Some of the causes (side effect of drugs, endogenous intoxication, etc.) of EPT are common, so it is likely one of the most common forms of tremor.

Pathophysiology

EPT relies on the same physiological mechanism as normal physiological tremor, and the physiology of normal tremor is meanwhile well defined. Two different physiological tremor mechanisms have been established. The first is based on simple mechanical properties. Any movable limb can be regarded as a pendulum with the capability to swing rhythmically, that is to oscillate. These oscillations automatically assume the resonant frequency of this limb, which is dependent on its mechanical properties—the greater its weight, the lower is its resonant frequency, and the greater the joint stiffness, the higher is this frequency. Any mechanical perturbation can activate such an oscillation. In the case of the hands, which are most often affected by tremors, the main and most direct mechanical influence comes from the forearm muscles. Indeed, it has been shown that the tremor measured in normal subjects during muscle activation mainly emerges from an amplification of the muscles’ effect on the hand at its resonant frequency.3–5 Thus, although the muscles show normal nonrhythmic isometric activity, they contribute to these resonant oscillations, which account for most of the tremor seen in the physiological situation.6 Such a pure resonant phenomenon does not produce pathological tremors as its amplitude is typically quite low. However, as this low-amplitude oscillation leads to rhythmic activation of muscle receptors, it activates segmental (spinal) or long (e.g., transcortical) reflex loops that can greatly enhance this oscillation. Such a reflex enhancement of the physiological mechanical oscillation is one well-established pathophysiological basis for the emergence of pathological tremor amplitudes in the case of EPT.7

The second less frequent mechanism in physiological tremor is a transmission of oscillatory activity within the central nervous system to the peripheral muscles. The rhythmic activity of the muscles then leads to tremor. In contrast to the mechanical-reflex oscillations, central oscillations occur at the centrally determined frequency and are independent of the limbs’ mechanics.8,9 It has been shown that such a central tremor component is present in a small proportion of normal subjects in parallel to the more common mechanical reflex oscillations.6,10–12 An enhancement of this component is another basis for EPT.13 Such central oscillations generally are the most common pathophysiological mechanism in pathological tremors4,9,14 (see later). Accelerometric tremor recordings with different weight loads in combination with the electromyogram recorded from the driving muscles can distinguish between such central and peripheral resonant (possibly reflex enhanced) tremors.

Etiology

The causes of an enhancement of one or both of the physiological tremor components are diverse. The well-known trembling with excitement, fear, or anxiety is the most common form of EPT. It is believed to be mediated through an increased sympathetic tone that results in a β-adrenergically driven sensitization of the muscle spindles increasing the gain in the reflex loops.7 A similar origin via the sympathetic nervous system has been proposed for the tremor in reflex sympathetic dystrophy.15 The majority of other causes for EPT are related to drugs or toxins that can enhance the peripheral and the central component of physiological tremor (see Toxic Tremors).

Differential Diagnosis

As both EPT and early essential tremor are not accompanied by any other neurological symptoms, they can be difficult to distinguish. The positive family history in essential tremor, its chronic course, and the lack of an overt cause for the tremor are important hints. Sometimes the diagnosis can only be made after having observed the tremor for some time. EPT is usually bilateral and thus any tremor manifesting unilaterally, even with a high frequency and a pure postural component, must be suspected of being a symptomatic tremor (see Table 33-2). Electrophysiology (spectral analysis of accelerometry and electromyography) can be helpful in cases where EPT emerges from a reflex enhancement of physiological tremor, as essential tremor is a centrally driven tremor.14,16 Electromyographic bursts below 8 Hz seem to be in favor of essential tremor rather than EPT.17

ESSENTIAL TREMOR

Essential tremor is a slowly progressive tremor disorder that causes severe disability but is not life limiting. It is defined by the following core criteria:1,18

Bilateral tremor of the hands or forearms with predominant kinetic tremor and resting tremor only in advanced stages of the disease

Bilateral tremor of the hands or forearms with predominant kinetic tremor and resting tremor only in advanced stages of the disease And absence of other neurological signs with the exception of cogwheel phenomenon and slight gait disturbances

And absence of other neurological signs with the exception of cogwheel phenomenon and slight gait disturbancesSome criteria involve the severity of the tremor,19 which are falling short when applied to a slowly developing condition. But the criteria mentioned here also have difficulties as the differential diagnosis to enhanced physiological tremor is not yet clear enough.

Essential tremor usually starts with a postural tremor but can still be suppressed during goal-directed movements. In advanced stages an intention tremor can develop. This has been found in roughly 50% of an outpatient population and is accompanied by signs of cerebellar dysfunction of hand movements like movement overshoot and slowness of movements.20 In more advanced stages a tremor at rest can develop. Also, a mild gait disorder prominent during tandem gait is frequently found.21 Oculomotor disturbances are found with subtle electrophysiological techniques but cannot be detected by means of clinical assessment. The condition may begin very early in life and the incidence is increasing above 40 years with a mean onset of 35 to 45 years in different studies and an almost complete penetrance at the age of 60.22,23 The topographic distribution shows hand tremor in 94%, head tremor in 33%, voice tremor in 16%, jaw tremor in 8%, facial tremor in 3%, leg tremor in 12%, and tremor of the trunk in 3% of the patients.22–24 In some of the topographic regions (e.g., head, voice, and chin), tremor may occur in isolation.25 About 50% to 90% of the patients improve with ingestion of alcohol, which can be used as an important feature of medical history.

So far only few data are available on the progression of the condition and have shown a decrease of tremor frequency and a tendency to develop larger amplitudes.26 Intention tremor develops at various intervals between 3 and 30 years after the onset of postural tremor.20 The disease-related disability varies significantly and is dependent on the severity of intention tremor.27 For a generic quality of life questionnaire (SF-36), essential tremor patients scored worse in all eight SF-36 domains. Tremor severity correlated with some of the physical domains as well as with social function of the mental domains.28 An essential tremor-specific quality of life questionnaire has been validated.29 Up to 25% of the patients seeking medical attention must change jobs or retire from work.30

Nontremor symptoms have been described as a mild frontal dysexecutive syndrome31 and slight personality changes,28,32 which have both been interpreted to reflect a cerebellar dysfunction. Furthermore, a deficit of hearing33 and olfaction was found independent from disease duration and severity.34

Epidemiology

The prevalence of essential tremor has been assessed in many studies to be between 1.3% and 5.1% when only studies with convincing methodological approaches are taken into account.35 Such methodological problems are the lack of a test for the validation of the diagnosis as many other conditions may manifest with a slowly progressive action tremor. Convincing studies on the incidence are not available. Patients with essential tremor were found in retrospective studies to live longer than those without essential tremor,36 but other studies failed to find this. There is at least no evidence for a shortening of life span due to essential tremor.

Etiology

The majority of cases are hereditary. The families that have been described hitherto have shown an autosomal dominant inheritance with an almost complete penetrance at the age of 60 years. Twin studies allow to estimate the heritability, which was estimated to be low in a relatively small study37 but almost 100% in a larger study of twins of old age (>70 years).38 Thus, in families with familial essential tremor, the heritability seems to be extremely high and the role of environmental factors is probably limited. However, there is a proportion of approximately 20% to 40% of the patients who have no family history of essential tremor and therefore may not be genetic. Linkage has been found for two chromosomes, 3q1339 and 2p22.40 For the latter locus, a rare variant of the HS1-BP3 protein has been described,41 which binds to motor neurons and Purkinje cells and regulates the Ca2+/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase activation of tyrosine and tryptophan hydroxylase. Further confirmation is needed. On chromosome 3, a gain of function-mutation of the DRD3-gen is considered to be responsible. The environmental factors that may cause tremor are also understudied. β-Carboline alkaloids are known to cause tremor in animals and humans42 and were found to be elevated in the blood of patients with essential tremor.43 Also, the lead concentration was found to be elevated in essential tremor.44 Controlled epidemiological studies are necessary.

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of essential tremor was reviewed45,46 and is covered only briefly here. Essential tremor is likely enhanced by peripheral reflex mechanisms, but its main origin must be within the central nervous system for various reasons: either a preformed mechanism in the brain that is producing rhythmic movements is overactive or pathology has created a system to oscillate, which is usually stable. The oscillator is most likely located within the olivocerebellorubral triangle. The cerebellum shows some mild to moderate signs of malfunction demonstrated in a number of motor tests. The rhythmic movement is obviously mediated through different channels of both hemispheres for the different extremities as the trembling is independent in the four extremities.47 It is assumed that the rhythmic discharges are mediated through the thalamus to the premotor and motor cortex projecting down to the motor neurons. At both locations, tremor-related activity can be detected with electrophysiological techniques. Alternative pathways, mainly from the cerebellar nuclei through reticulospinal pathways to the spinal cord, have been proposed.

Differential Diagnosis

The following criteria are considered red flags for the diagnosis (see also Table 33-2):

Treatment

Tremor of the Hands

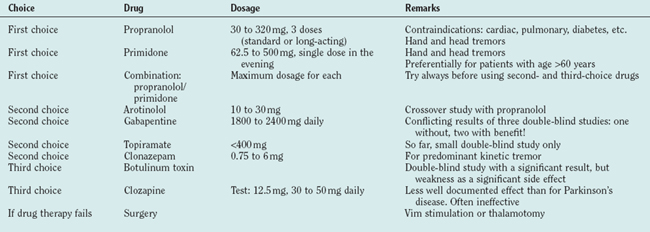

Propranolol and primidone are the drugs of first choice for this indication, and both have been carefully studied (for review, see Findley48). Propranolol was introduced in 197149 as a treatment for essential tremor. Drugs with predominant β1 effects have been shown to be less effective than those acting on the β2 receptor, and none has proved superior to propranolol. Only 25% maintain their initial good response for 2 years. Contraindications are cardiac insufficiency or arrhythmia and diabetes. As propranolol acts on the peripheral (reflex) enhancement of tremors, it is helpful for many other tremors like parkinsonian or cerebellar tremor.50,51 Primidone is efficient for essential tremor52 but tachyphylaxia may occur. The major problems are early adverse effects with nausea, dizziness, sedation, and headache. The combination of propranolol and prinidone is recommended whenever one of the drugs is insufficient. Arotinolol has been tested in a crossover study with a similar effect as propranolol.53 Gabapentin is also effective following two double-blind studies,54 but another double-blind study showed no convincing effect.55 Topiramate was shown to be effective in a small double-blind study.56 Levetiracetam is just beginning to be explored for the treatment of essential tremor and single-dose studies are promising.57,58 Acetazolamide (and methazolamide) are not significantly better than placebo.59 Alprazolam is helpful in essential tremor.60 Clonazepam is recommended for patients with predominant action and intention tremor in essential tremor61 but not effective in uncomplicated essential tremor.62 Botulinum toxin at a dosage of 50 units or 100 U of Botox has a significant but clinically limited effect and carries a high risk of a clinically meaningful but completely reversible paresis63 (Table 33-3 and, for drug dosages, Table 33-4).

Surgery is the accepted treatment for patients resistant to medical treatment and severe disability. Multicenter studies have shown that thalamic deep-brain stimulation is effective,64–67 and one study has shown that deep-brain stimulation of the Vim has a better effect than Vim-thermocoagulation and even fewer side effects.68 The selection of patients for surgery is a crucial point for a good therapeutic effect. Each patient should test the treatments of first choice before surgery and each patient proposed for surgery must have a significant handicap. Gamma knife surgery for the treatment of tremors is proposed in some centers, but prospective studies are lacking and the risks are not yet fully clear.69–71

Head and Voice

Pharmacological treatment of essential head and voice tremor is less efficient than the one of hand tremor. Propranolol and primidone, each alone or both combined, have been recommended72,73 for essential head tremor. Clonazepam is often recommended for this indication, but careful studies are not available. One of the promising therapies for head tremor is the local injection of botulinum toxin.74 Deep brain stimulation is also effective for head and voice tremor. As bilateral thalamotomies carry a high risk of dysarthria and bilateral interventions show better effects on these “midline” tremors,75,76 mostly Vim stimulation is applied.66,77 An evidence-based medicine-based review on treatments for essential tremor was published.78

ORTHOSTATIC TREMOR

Primary orthostatic tremor is a unique tremor syndrome79,80 characterized by a subjective feeling of unsteadiness during stance but only in severe cases during gait. Some patients show sudden falls. None of the patients has problems when sitting and lying. The only clinical finding is sometimes visible but mostly only palpable fine-amplitude rippling of leg muscles. This tremor is suspected mainly based on the complaints of the patients rather than on clinical findings.

Epidemiology

Orthostatic tremor is a relatively rare condition (only small case series have been published adding up to fewer than 200 cases), but epidemiological data are lacking. Other movement disorders are common in orthostatic tremor. The condition occurs only in patients older than 40 years, and in the series of Gerschlager and colleagues,81 the mean age at onset was lower for women (50 years) compared with men (60 years). So far, it is not considered a hereditary disease.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

Orthostatic tremor is considered an idiopathic condition. However, other movement disorders often occur simultaneously: Parkinson’s disease, vascular parkinsonism, and Restless legs syndromes (RLS) have all been described in orthostatic tremor, but there is no convincing evidence that any of these conditions are pathophysiologically related. It is of special interest that dopaminergic terminals are significantly reduced in this condition82 but clinical trials with L-dopa and dopamine agonists are usually unsuccessful.

Surface electromyography (e.g., from the quadriceps femoris muscle) while standing shows a typical (pathognomic) 13- to 18-Hz burst pattern. All of the leg, trunk, and arm muscles show this pattern, which is in many cases absent during tonic innervation when sitting and lying.83–85 Besides asterixis, orthostatic tremor is the only tremulous condition for which electromyography is mandatory for the diagnosis. Arm tremor may occur in roughly one half of the patients and is usually more evident during stance.86,87 The high-frequency electromyographic pattern is coherent in all the muscles of the body,88 leading to the hypothesis that a bilaterally descending system must underlie orthostatic tremor. Such projections originate only from the brainstem and not from the hemispheres. Therefore, the generator for this tremor is assumed to be located within the brainstem or cerebellum.89

Treatment

Orthostatic tremor has been documented to be responsive to clonazepam and primidone.90 Valproate and propranolol were applied in single cases with varying success. Abnormalities of dopaminergic innervation of the striatum have been described, although L-dopa has not consistently shown efficiency.82,91 According to small double-blind studies92,93 and our experience, gabapentin seems to have an excellent and most consistent beneficial effect.94 We use it as the drug of first choice for orthostatic tremor (1800 to 2400 mg daily). The drug of second choice, in our hands, is clonazepam.

PARKINSONIAN TREMORS

Parkinsonian tremor has been defined as tremor that occurs in Parkinson’s disease.1 The most common forms are the following:

Classic parkinsonian tremor (type I) is defined as tremor at rest (ideally resting on a couch) that increases in amplitude under mental stress and is suppressed during initiation of a movement and often during the course of a movement. Tremor frequency is 4 to 6 Hz but can be as high as 6 Hz, especially in early Parkinson’s disease. It may also be seen in the hands during walking or when sitting as a typical pill-rolling tremor of the hand. The postural/kinetic tremor (with similar frequencies for rest and postural/kinetic tremors) seems to be a continuation of the resting tremor under postural and action conditions. The frequencies for resting and postural/action tremor can be considered to be equal if they do not differ by more than 1.5 Hz. Unilateral tremor or leg tremor are often seen and are typical for type I tremor.

A clinically important specific variant of Parkinson’s disease is the monosymptomatic tremor at rest or benign tremulous parkinsonism. This is defined as a classic Parkinson’s disease type I tremor without other symptoms sufficient to diagnose Parkinson’s disease.1

In some patients, a second form of postural and action tremor with a different frequency from resting tremor (>1.5 Hz) may occur, which is labeled type II tremor. This postural/action tremor can be extremely disabling. Some patients have a predominant postural tremor in addition to their resting tremor. The postural/action tremor has a higher and non-harmonically related frequency to the resting tremor. This form is rare (<15% of patients with Parkinson’s disease) and has often been described as a combination of an essential tremor with Parkinson’s disease.95 Some of these patients had their postural tremor long before the onset of other symptoms of Parkinson’s disease. A high-frequency action tremor also described as “rippling” is often found in Parkinson’s disease and has been described as type III tremor in Parkinson’s disease.1

Etiology and Pathophysiology

It is one of the mysteries of Parkinson’s disease that the typical type I tremor is a symptom with such a high specificity for Parkinson’s disease but that the symptom of tremor does not correlate with disease progression96,97 nor does tremor severity correlate with the amount of dopaminergic degeneration measured with positron emission tomography or single-photon emission computed tomography imaging.98–100 Pathology suggests that in patients with predominant tremor the retrorubral Aδ part of the substantia nigra is specifically degenerating101–103 but that there are no clear-cut differences in the positron emission tomography imaging of the presynaptic or postsynaptic dopaminergic terminals in patients with monosymptomatic tremor at rest compared with classic Parkinson’s disease patients.104,105 Interestingly, reduction in 5-hydroxytryptamine1A binding in the midbrain raphe region is correlating with tremor severity but not with rigidity or bradykinesia.106 Thus, degeneration of transmitter systems other than dopamine may be responsible for the erratic behavior of tremor as a symptom in Parkinson’s disease. Nevertheless, L-dopa and dopamine agonists are potent drugs to treat Parkinson’s disease tremor.

Beyond all of these unsolved problems, animal experiments and human data converge to suggest that parkinsonian tremor is generated within the basal ganglia.107 In the 1-methyl 4-phenyl 1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) model of Parkinson’s disease it has been shown that the cells within the basal ganglia loop are topographically organized through the whole loop and well segregated for the different muscle groups and functional regions. In MPTP animals, these cells become abnormally synchronized, and this may be the reason for synchronized activity leading to peripheral tremor.108 Recordings in humans are compatible with this view.109

Treatment

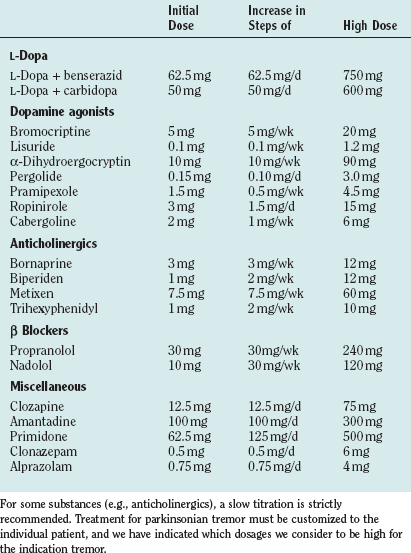

Drug treatments differ for the different forms of tremor in Parkinson’s disease (for drug dosages, see Table 33-4). Our personal approach to the treatment of patients is included in Table 33-5.

L-Dopa is the most effective treatment for the majority of symptoms in Parkinson’s disease. Among the tremors in Parkinson’s disease, mainly the resting tremor is improved, but other forms may also respond. Generally, the effect on tremor is highly variable in patients with Parkinson’s disease, and the tremor may even worsen, especially for the action tremor with frequencies different from the resting tremor frequency. All of the available double-blind studies of different dopamine agonists failed to demonstrate a superior effect of one or the other agonist on tremor, although all of them obviously have a significant effect. For pramipexol, a double-blind-study has shown a favorable effect on tremor.110 Although the treatment of tremors with anticholinergics is often recommended, there are only a few double-blind studies. The anticholinergic bornaprine has been found to be effective in two double-blind studies.111,112 Trihexyphenidyl has been tested alone and compared with amantadine and L-dopa.113 Possible side effects are dry mouth, visual disturbances, constipation, glaucoma, disturbance of micturition, and memory deficits. Especially in elderly subjects, confusional states can occur, which are reversible after cessation of the drug. Discontinuation may induce a severe rebound effect. A study has provided ample evidence that patients treated with anticholinergics have a higher incidence of Alzheimer pathology.114

The favorable effect of clozapine on rest tremor has been confirmed in several studies,115,116 which have shown a good effect on resting tremor—even when other drugs failed.117 No tolerance has been observed over 6 months. The dosage was 18 to 75 mg. Major side effects are sedation and leukopenia as a serious, even lethal complication in some patients.

Functional neurosurgery is a useful treatment for some patients who cannot be treated otherwise. Thalamic thermocoagulation or deep brain stimulation (DBS) of the Vim improves tremor but does not improve akinesia. Lesional surgery cannot be applied bilaterally due to speech disturbances (but DBS can) and therefore is no longer the surgical treatment of first choice.68 Pallidotomy, as well as stimulation of the pallidum, also improves tremor. Subthalamic nucleus (STN) stimulation improves tremor118,119 as well as akinesia and rigidity and is the preferred surgery. Further controlled studies are necessary.

DYSTONIC TREMOR SYNDROMES

Different forms of tremor can be associated with dystonia. Typical dystonic tremor occurs in the body region affected by dystonia. It is defined120 as a postural/kinetic tremor usually not seen during complete rest. Usually, these are focal tremors with irregular amplitudes and varying frequencies (mostly below 7 Hz). Some patients exhibit focal tremors even without overt signs of dystonia. These tremors have been included with dystonic tremors121 because in some of them, dystonia develops later.

Tremor associated with dystonia is a more generalized form of tremor in extremities that are not affected by the dystonia. This is a relatively symmetrical, postural, and kinetic tremor usually showing higher frequencies than actual dystonic tremor, often seen in the upper limbs in patients with spasmodic torticollis.122

Epidemiology

The prevalence of dystonic tremor is not known. In one Brazilian cross-sectional study, it was estimated that around 20% of patients with dystonia present with postural tremor.123 This proportion does not differ between primary and secondary dystonia but seems to be more common in cervical dystonia than in other locations.124 In a large survey among patients from a large Indian movement disorder center, dystonic tremor constituted about 20% of all patients presenting with non-parkinsonian and noncerebellar tremors (essential tremor, 60%).125

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Dystonic tremor is still an entity that is under debate, and different definitions have been proposed by clinicians.126–128 Its pathophysiology is largely unknown but is likely related to the central nervous system (basal ganglia) abnormality postulated for dystonia itself.120 Tremor associated with dystonia may be a “forme fruste” of essential tremor.127 However, it is not yet clear if they share common genes (the DYT1 locus is already excluded), and the pathophysiological mechanisms seem to be different in some of the patients.122

Differential Diagnosis

In many patients with dystonic tremors, antagonistic gestures lead to a reduction of the tremor amplitude. This is well known for dystonic head tremor in the setting of spasmodic torticollis. A reduction in tremor is seen when the patient touches the head or only lifts the arm.129 As this sign is absent in essential head tremor, it can be an important differential diagnostic hint in unclear head tremors in which the dystonic posture is not obvious. The effect of these maneuvers can be difficult to observe clinically, and it can be helpful to record surface electromyography from the affected muscles and look for electromyographic suppression.129 Other important but less specific differential diagnostic clues are the focal nature and relatively low frequency of dystonic tremor (see Table 33-2). The tremor associated with dystonia is more difficult to separate from essential tremor, especially when the accompanying dystonia has not evolved completely.

Treatment

A positive effect of propranolol has been described earlier in studies of dystonic head tremor. The effectivity of botulinum toxin for dystonic head130 tremor and in tremulous spasmodic dysphonia is well documented. A double-blind study has also documented the efficacy of botulinum toxin for hand tremor,63 but the use of this drug for this indication is limited because of the paresis associated with this treatment. Severe cases in the setting of a generalized dystonia have been successfully treated with deep brain stimulation of the pallidum.131 Stimulation of the ventrolateral thalamus can also alleviate the tremor drastically but can occasionally lead to worsening of the dystonia itself. Tremor associated with dystonia often responds to the medication for classic essential tremor (for drug dosages, see Table 33-4).

CEREBELLAR TREMOR SYNDROMES

Epidemiology and Etiology

This type of tremor can be caused by insults of various etiologies and degenerations, so no epidemiological data are available. One of the most common causes of cerebellar tremor certainly is demyelinating lesions in multiple sclerosis.132 Cerebellar strokes can also manifest with tremor, especially when the brainstem is involved.133 Degenerations of cerebellar neurons of various etiologies often produce tremor. Whereas the hereditary ataxias are rare syndromes, toxic cerebellar degeneration due to alcohol abuse predominantly of the anterior lobe is common and often manifest with low-frequency (2 to 3 Hz) stance tremor in the anteroposterior direction.134

Pathophysiology

The pathophysiology of the classic cerebellar intention tremor seems to be distinct from the mechanisms underlying most of the other central tremors in that it most likely does not emerge from oscillating groups or loops of neurons but is due to altered characteristics of feedforward or feedback loops. It is meanwhile well established in animals and humans135–137 that one of the striking abnormalities in cerebellar dysfunction is a delay of the second and third phases of the triphasic electromyographic pattern in ballistic movements138 or a delay of the reflexes regulating stance control.139 During goal-directed movements or sway during stance, this causes the breaking movement to occur late and thereby produce an overshoot, in turn producing a quasi-rhythmic movement that is compatible with intention tremor during goal-directed movements or the low-frequency body tremor during stance.

Differential Diagnosis

Intention tremor is a unique form of tremor that can usually be separated from other tremor forms clinically. However, the fact that intention tremor can also occur in advanced essential tremor45 can make the differentiation difficult. The most important clinical clue in this situation is the degree to which ataxia is present and the absence of clinically detectable oculomotor abnormalities in essential tremor. whereas in essential tremor only a mild dysmetria45 and tandem gait disturbance21 have been described, these dominate the cerebellar syndrome, in which lesions or atrophy can often be seen in brain imaging studies (see Table 33-2).

Treatment

Cerebellar tremors are difficult to treat and good results are rare. Double-blind studies are lacking. Studies with cholinergic substances (physostigmine, lecitine [a precursor of choline]) have shown improvement in some patients but failed in the majority. Isoniazid failed to show significant results.140 5-HTP has been found to be effective in some patients.141,142 Another proposal has been to administer amantadine. Open studies or single-case observations have shown favorable results with propranolol, clonazepam, carbamazepine, tetrahydrocannabiol, and trihexyphenidyl. Limited improvements have been observed after loading of the shaking extremity, but most clinicians do not use it because the patients adapt rapidly to the new weight. Cannabis is not effective.143 Probably the best symptomatic improvement can be obtained with stereotactic high-frequency stimulation or thalamotomy in select patients.68,144,145 Functional outcome after surgery, however, greatly varies and depends on the presence of other motor symptoms of the disease; patients with tremor in Multiple Sclerosis (MS) with a frequency above 3 Hz and significant tremor-related disabilities were found to respond favorably.144 Accelerometric tremor recordings and frequency analysis may help to distinguish patients with predominant MS tremor from those with tremor and ataxia. The long-term follow-up in a larger cohort has not yet been assessed.

HOLMES’ TREMOR

Pathophysiology and Etiology

It is generally accepted that this unique tremor form is caused by lesions that seem to be centered in the brainstem/cerebellum and the thalamus. The pathophysiological basis of Holmes tremor is a combined lesion of the cerebellothalamic and nigrostriatal systems as suggested by autopsy data,146 positron emission tomography data,147 and clinical observations.148,149 Any lesion involving fiber tracts from both systems can produce this tremor. The exact location of the lesions seen in these patients may vary. Because of these lesions the tremors can be accompanied by a cerebellar as well as parkinsonian syndrome. Central oscillators are causing this tremor. It seems likely that the rhythm of resting tremor is usually blocked during voluntary movements by the cerebellum. If this cerebellar compensation is absent, the rhythm of rest tremor spills into movements,148 thereby producing the low-frequency intention (action) tremor.

Differential Diagnosis

A specific tremor syndrome associated with thalamic lesions can be difficult to differentiate from Holmes tremor. It has been presented often in the past but was further analyzed with modern imaging techniques. The label thalamic tremor150 has been used for this entity. A more detailed study has shown that this tremor is part of a specific dystonia-athetosis-chorea-action tremor following lateral-posterior thalamic strokes.151,152 The combination of tremor, dystonia, and a severe sensory loss following this stroke seems to be the important clue for the diagnosis. The “thalamic” tremor itself is a mixture of action tremor with an intentional component and dystonia in the setting of a well-recovered severe hemiparesis. Proximal segments are often involved. This tremor syndrome is also developing with a certain delay after the initial insult.

Cerebellar tremor that continues under seemingly resting conditions due to a lack of relaxation can be mistaken for Holmes tremor. The irregularity, the lower frequency, and an accompanying parkinsonian syndrome can help to recognize Holmes tremor in this situation (see Table 33-2).

Treatment

No generally accepted therapy is available. Nevertheless, treatment is successful in a higher percentage than for patients with cerebellar tremor. Some patients respond to L-dopa, anticholinergics, or clonazepam (for drug dosages, see Table 33-4). The effect of functional neurosurgery for this tremor syndrome is poorly documented. Such patients have been operated on but they are diagnosed as having post-traumatic tremors or poststroke tremors and the clinical features are not described in detail. Several patients received thalamic surgery (lesion or DBS153–155) with some improvement.

PALATAL TREMOR SYNDROMES

Palatal tremors are rare tremor syndromes that were earlier classified among the myoclonias (palatal myoclonus).156 Because they are rhythmic, they have been reclassified among the tremors. Palatal tremor can be separated into two forms.157,158 Symptomatic palatal tremor (SPT) is characterized by rhythmic movements of the soft palate (levator veli palatini). This is clinically visible as a rhythmic movement of the edge of the palate. Other brainstem-innervated (leading to oscillopsia in case of eye muscle involvement) or extremity muscles can also be involved.146 It typically follows a brainstem/cerebellar lesion with a variable delay159,160 and is often associated with a cerebellar syndrome.161 Essential palatal tremor occurs without any overt central nervous pathology and is characterized by rhythmic movements of the soft palate (tensor veli palatini), usually with an ear click. The tensor contraction is visible as a movement of the roof of the palate. Extremity or eye muscles are not involved.158,161,162

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Although the pathophysiological basis of essential palatal tremor is unknown, the emergence of SPT has been studied in detail and carries important implications for central mechanisms of tremors in general. After the cerebellar/brainstem lesion, an inferior olivary pseudohypertrophy (which can be demonstrated on MRI) develops most likely as a consequence of an interruption of inhibitory GABAergic fibers terminating in the inferior olive.158 It is well established that inferior olivary neurons are prone to oscillate spontaneously and can be easily synchronized through gap junctions.163 The disinhibition and hypertrophy lead to enhanced synchronized oscillations and build the basis for the rhythmic movement disorder. Interestingly, this rhythm is also reflected in rhythmic electromyographic inhibition in extremity muscles, sometimes leading to a mild postural tremor.158,164 Therefore, it has been postulated that the inferior olive (and the olivocerebellar system) may be a key structure in producing postural tremors8 and that these tremors are characterized by a rhythmic inhibition of ongoing contractions rather than rhythmic activation, which may be the basis of the etiologically different resting tremors.158

Treatment

Oscillopsia is difficult to treat. Single cases have been described with a favorable response to clonazepam. Other oral drugs that have been proposed are trihexyphenidyl and valproate. Botulinum toxin has been used for the treatment of oscillopsia. The toxin can be injected into the retrobulbar fat tissue, or specific muscles can be targeted selectively.165,166 So far no controlled studies are available. In our hands, this treatment is helpful for some patients but is not always accepted for long-term use.

For the treatment of extremity tremors, only single case reports have described a response to clonazepam167 or trihexiphenidyl.168

The only complaint of patients with essential palatal tremor is the ear click. A number of medications have been reported to be successful: valproate,169 trihexyphenidyl,168 and flunarizine.170 Sumatriptane has been found to be effective in a few patients171,172 but was unsuccessful in others.173 The antagonism of 5-hydroxytryptamine receptors may thus play a role at least for some of the patients. As a long-term therapy, this drug is not applicable for various reasons. The most established therapy is the treatment of the click by injection of botulinum toxin into the tensor veli palatini.174 Low dosages of botulinum toxin (e.g., 4 to 10 units of Botox) are injected under electromyographic guidance. The critical point is to ascertain by endoscopy and electromyography with an electromyography injection needle (isolated up to the tip) that the toxin is definitely injected in the tensor muscle. Spread of botulinum toxin in the soft palate or too large dosages can otherwise cause severe side effects. Although we have never seen any such complications in our patients, it must be mentioned that the injection of botulinum toxin into the palatal muscles in rabbits has been introduced as an animal model for middle ear infections (for drug dosages, see Table 33-4).

TREMOR SYNDROMES IN PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY

Several peripheral neuropathies regularly manifest with tremors (Table 33-1). The tremors are mostly postural and action tremors. The frequency in hand muscles can be lower than in proximal arm muscles. Abnormal position sense need not be present.

Epidemiology

Dysgammaglobulinemia and chronic Guillain-Barré syndrome are the acquired neuropathies manifesting most frequently with tremor. In a series of 62 patients with dysgammaglobulinemic polyneuropathy, postural and action tremor of the hands was present in 70% to 80% of the cases.175 However, it only rarely represents the dominant source of disability in these patients.176

A similar type of tremor can be observed in around 40% of patients with hereditary polyneuropathy. Many of these patients have a family history of tremor.177

Pathophysiology and Etiology

The tremor in dysimmune neuropathies seems to be somewhat related to the severity of the peripheral neuronal damage,178 and it has been postulated that an abnormal peripheral feedback to central tremor generating structures could be the basis for the tremor enhancement in this situation.179

The tremor in hereditary polyneuropathy seems to be largely unrelated to the severity of neuropathic syndromes, and it may also occur in family members without a neuropathy. Thus, it has been suggested that it is pathogenetically related to essential tremor.177 There is an ongoing debate as to whether the combination of a hereditary neuropathy with postural tremor (Roussy-Lévy syndrome) actually constitutes a distinct disease entity.180

Treatment

No convincing therapies are reported for this type of tremor. Successful treatment of the underlying neuropathy can improve the tremor in some of the patients.178 In our hands, propranolol and primidone have been helpful for some patients at similar dosages as for essential tremor. One patient was successfully implanted with DBS electrodes.181

PSYCHOGENIC TREMOR

Psychogenic tremors have very diverse clinical manifestations. Most of them are action tremors but many also remain during rest and often show very unusual combinations of rest/postural and intention tremors.182 Typical clinical features are a sudden onset and sometimes spontaneous remissions, decrease of tremor amplitude or variable frequency during distraction, selective disability, and a positive “coactivation sign.” (This is tested as with rigidity testing, at the wrist. Variable, voluntary-like force exertion can be felt in both movement directions.183) Some of the patients have a history of somatizations in the past or additional, unrelated (psychogenic) neurological symptoms and signs.183

Epidemiology

In a large series of 842 patients presenting with a movement disorder, only 3.3 % were diagnosed with a psychogenic movement disorder. Among those, psychogenic tremor was the most common diagnosis (50%).184

Pathophysiology and Etiology

Two pathogenetic mechanisms seem to play a role in psychogenic tremor. Voluntary-like rhythmic movements can be detected by a coupled (coherent) tremor oscillations in different limbs. This resembles the situation in voluntarily sustained rhythmic movements in normal subjects, as it is extremely difficult to keep up two completely independent rhythms in different limbs.185,186 In pathological, organic tremor (clearly involuntary rhythmic movements), the oscillations are typically independent between different limbs.47,187 Such independent rhythms can also be found in psychogenic tremor patients.188 They most likely represent physiological but involuntary oscillations, such as clonus-like mechanisms, which are enhanced by the ongoing co-contraction of antagonistic muscles detected as the coactivation sign.183 These findings may easily explain the motor control mechanisms underlying these tremors. They do not allow conclusions to be drawn on the underlying psychological mechanisms.

Differential Diagnosis

Psychogenic tremors manifest very variably and can mimic virtually all organic tremors. The tremor phenomenology does not help to differentiate them. The typical conditions of tremor appearance or disappearance, enhancement or attenuation described earlier are important clinical clues. The coupling between the oscillations in both arms, which is present only in psychogenic tremor and is absent in organic tremors, can be used as an electrophysiological diagnostic tool. The surface electromyography from both arm muscles can be analyzed using “coherence,” which is a reliable mathematical measure of the oscillatory coupling. If the patients show only unilateral tremor, a voluntarily sustained rhythmic hand movement on the unaffected side is related to the tremor on the affected side (“coherence entrainment test”).189 This test is very specific, and the entrainment of psychogenic tremor by a contralateral rhythmic movement can sometimes be visible even clinically. However, it is not very sensitive; some psychogenic tremor patients show unrelated rhythms in different limbs resembling organic tremors.188 An accelerometric quantification of the distractibility can also be helpful.190

Treatment

No studies on the treatment effects in psychogenic tremor are available.191 Psychotherapy is helpful only in the minority of patients. We recommend physiotherapy aiming at a decontraction of the muscles during voluntary movements. Additionally, we administer propranolol at medium or high dosages to desensitize the muscle spindles, which are necessary to maintain the clonus mechanism in these patients. Conclusive data on the prognosis and long-term outcome in these patients are lacking, but the prognosis is generally believed to be poor.192

DRUG-INDUCED AND TOXIC TREMORS

Drug-induced tremors can manifest with the whole range of clinical features of tremors depending on the drug and probably on individual predisposition of the patients. The most common form is enhanced physiological tremor following, for example, sympathomimetics or antidepressants. Another frequent form is parkinsonian tremor following neuroleptic or, more generally, antidopaminergic drugs (dopamine receptor blockers, dopamine-depleting drugs such as reserpine, flunarizin, etc). Intention tremor may occur following lithium intoxication and ingestion of some other substances. The withdrawal tremor from alcohol or other drugs has been characterized as enhanced physiological tremor with tremor frequencies mostly above 6 Hz. However, this has to be separated from the intention tremor of chronic alcoholism, which is most likely related to cerebellar damage following alcohol ingestion.

A specific variant is tardive tremor associated with long-term neuroleptic treatment.193,194 The risk factors to develop this tremor are not well known, but many clinicians believe that patients with essential tremor, older age, and females represent a higher risk to develop this tremor. Its frequency range is 3 to 5 Hz, it is most prominent during posture but is also present at rest and during goal-directed movements.

The tremor in Wilson’s disease can also be regarded a toxic tremor as it results from copper toxicity. All kinds of movement disorders, including cerebellar syndromes, can be observed.195 Tremor is one of the most common neurological manifestations and occurs in around 30% to 50% of the patients. Resting, postural, and kinetic tremors have all been described.

The treatment of these tremors is usually to stop the medication or toxin ingestion. If this is not possible, propranolol may be tried in action tremors if it does not have negative interactions with the causative drug. It has been shown to be effective in a small open series of valproate-induced tremors.196 Treatment attempts for tardive tremor have been with trihexyphenidyl or clozapine. The treatment of Wilson’s disease with copper chelators (D-penicillamine) also improves the tremor and other neurological manifestations.197,198 In patients with very severely disabling neurological symptoms (tremor), a liver transplantation may be considered even with normal liver function.199

MYOCLONUS

Myoclonus is defined as a sudden, brief, shocklike involuntary movement caused by muscle contractions or inhibitions. It can be of cortical, subcortical, or spinal origin and occurs in different neurodegenerative diseases, in focal structural lesions of the respective region of the central nervous system, and as idiopathic diseases.200 It can be difficult to differentiate from tremor when the myoclonic jerks occur repetitively with only short intervals sometimes looking rhythmically. This type of rhythmic myoclonus is not well defined but has been described as low frequency (usually below 5 Hz) muscle jerks topographically limited to segmental levels.

Cortical tremor is considered a specific form of rhythmic myoclonus201,202 manifesting with high-frequency, irregular tremor-like postural and action myoclonus. On electrophysiological analysis, they show the typical features of cortical myoclonus with a related electroencephalographic spike preceding the electromyographic jerks and often enhanced long-loop-reflexes and/or giant SEP. This form is mostly hereditary but has also been described in corticobasal degeneration203,204 and even after focal lesions205 or celiac disease.206

Clonus also is a rhythmic movement mostly around one joint elicited through the stretch reflex loop and increasing in strength (or amplitude) by maneuvers affecting the stretch reflex.207 Passive stretching of the muscles increases the force of clonus and serves as a diagnostic criterion.

CONCLUSIONS

Deuschl G, Bain P, Brin M, Ad Hoc Scientific Committee. Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Mov Disord. 1998;13:2-23.

Findley LJ, Koller WC, editors. Handbook of Tremor Disorders. New York: Marcel Dekker, 1995.

Pahwa R, Lyons KE, editors. Handbook of Essential Tremor and Other Tremor Disorders. Philadelphia: Taylor & Francis, 2005.

1 Deuschl G, Bain P, Brin M, Ad Hoc Scientific Committee. Consensus statement of the Movement Disorder Society on Tremor. Mov Disord. 1998;13:2-23.

2 Vallbo AB, Wessberg J. Organization of motor output in slow finger movements in man. J Physiol Lond. 1993;469:673-691.

3 Elble RJ, Randall JE. Mechanistic components of normal hand tremor. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol. 1978;44:72-82.

4 Hömberg V, Hefter H, Reiners K, et al. Differential effects of changes in mechanical limb properties on physiological and pathological tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatr. 1987;50:568-579.

5 Timmer J, Lauk M, Pfleger W, et al. Cross-spectral analysis of physiological tremor and muscle activity. I. Theory and application to unsynchronized electromyogram. Biol Cybern. 1998;78:349-357.

6 Raethjen J, Pawlas F, Lindemann M, et al. Determinants of physiologic tremor in a large normal population. Clin Neurophysiol. 2000;111:1825-1837.

7 Marsden CD, Gimlette TM, McAllister RG, et al. Effect of beta-adrenergic blockade on finger tremor and Achilles reflex time in anxious and thyrotoxic patients. Acta Endocrinol (Copenh). 1968;57:353-362.

8 Deuschl G, Raethjen J, Lindemann M, et al. The pathophysiology of tremor. Muscle Nerve. 2001;24:716-735.

9 Elble RJ. Central mechanisms of tremor. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;13:133-144.

10 Elble RJ. Characteristics of physiologic tremor in young and elderly adults. Clin Neurophysiol. 2003;114:624-635.

11 Elble RJ, Randall JE. Motor-unit activity responsible for 8- to 12-Hz component of human physiological finger tremor. J Neurophysiol. 1976;39:370-383.

12 Lyons KE, Pahwa R, Comella CL, et al. Benefits and risks of pharmacological treatments for essential tremor. Drug Saf. 2003;26:461-481.

13 Raethjen J, Lemke MR, Lindemann M, et al. Amitriptyline enhances the central component of physiological tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2001;70:78-82.

14 Deuschl G, Krack P, Lauk M, et al. Clinical neurophysiology of tremor. J Clin Neurophysiol. 1996;13:110-121.

15 Deuschl G, Blumberg H, Lücking CH. Tremor in reflex sympathetic dystrophy. Arch Neurol. 1991;48:1247-1252.

16 Raethjen J, Lauk M, Koster B, et al. Tremor analysis in two normal cohorts. Clin Neurophysiol. 2004;115:2151-2156.

17 Elble RJ, Higgins C, Elble S. Electrophysiologic transition from physiologic tremor to essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1038-1042.

18 Bain P, Brin M, Deuschl G, et al. Criteria for the diagnosis of essential tremor. Neurology. 2000;54:S7.

19 Louis ED, Ford B, Lee H, et al. Diagnostic criteria for essential tremor: a population perspective. Arch Neurol. 1998;55:823-828.

20 Deuschl G, Wenzelburger R, Loffler K, et al. Essential tremor and cerebellar dysfunction clinical and kinematic analysis of intention tremor. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 8):1568-1580.

21 Stolze H, Petersen G, Raethjen J, et al. The gait disorder of advanced essential tremor. Brain. 2001;124:2278-2286.

22 Bain PG, Findley LJ, Thompson PD, et al. A study of hereditary essential tremor. Brain. 1994;117(Pt 4):805-824.

23 Lou JS, Jankovic J. Essential tremor: clinical correlates in 350 patients. Neurology. 1991;41:234-238.

24 Koller WC, Busenbark K, Miner K. The relationship of essential tremor to other movement disorders: report on 678 patients. Essential Tremor Study Group. Ann Neurol. 1994;35:717-723.

25 Jankovic J. Essential tremor: clinical characteristics. Neurology. 2000;54:S21-S25.

26 Elble RJ. Essential tremor frequency decreases with time. Neurology. 2000;55:1547-1551.

27 Louis ED, Ford B, Wendt KJ, et al. Clinical characteristics of essential tremor: data from a community-based study. Mov Disord. 1998;13:803-808.

28 Lorenz D, Schwieger D, Moises H, et al. Quality of life and personality in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2006.

29 Troster AI, Pahwa R, Fields JA, et al. Quality of life in Essential Tremor Questionnaire (QUEST): development and initial validation. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2005;11:367-373.

30 Louis ED, Barnes L, Albert SM, et al. Correlates of functional disability in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2001;16:914-920.

31 Troster AI, Woods SP, Fields JA, et al. Neuropsychological deficits in essential tremor: an expression of cerebellothalamo-cortical pathophysiology? Eur J Neurol. 2002;9:143-151.

32 Chatterjee A, Jurewicz EC, Applegate LM, et al. Personality in essential tremor: further evidence of non-motor manifestations of the disease. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2004;75:958-961.

33 Ondo WG, Sutton L, Dat Vuong K, et al. Hearing impairment in essential tremor. Neurology. 2003;61:1093-1097.

34 Louis ED, Bromley SM, Jurewicz EC, et al. Olfactory dysfunction in essential tremor: a deficit unrelated to disease duration or severity. Neurology. 2002;59:1631-1633.

35 Louis ED, Ottman R, Hauser WA. How common is the most common adult movement disorder? Estimates of the prevalence of essential tremor throughout the world. Mov Disord. 1998;13:5-10.

36 Jankovic J, Beach J, Schwartz K, et al. Tremor and longevity in relatives of patients with Parkinson’s disease, essential tremor, and control subjects. Neurology. 1995;45:645-648.

37 Tanner CM, Goldman SM, Lyons KE, et al. Essential tremor in twins: an assessment of genetic vs environmental determinants of etiology. Neurology. 2001;57:1389-1391.

38 Lorenz D, Frederiksen H, Moises H, et al. High concordance for essential tremor in monozygotic twins of old age. Neurology. 2004;62:208-211.

39 Gulcher JR, Jonsson P, Kong A, et al. Mapping of a familial essential tremor gene, FET1, to chromosome 3q13. Nat Genet. 1997;17:84-87.

40 Higgins JJ, Loveless JM, Jankovic J, et al. Evidence that a gene for essential tremor maps to chromosome 2p in four families. Mov Disord. 1998;13:972-977.

41 Higgins JJ, Lombardi RQ, Pucilowska J, et al. A variant in the HS1-BP3 gene is associated with familial essential tremor. Neurology. 2005;64:417-421.

42 Lucotte G, Lagorde JP, Funalot B, Sokoloff P. Linkage with the SergGly DRD3 polymorphism in essential tremor families. Clin Genet. 2006;69:437-440.

43 Louis ED, Zheng W, Jurewicz EC, et al. Elevation of blood beta-carboline alkaloids in essential tremor. Neurology. 2002;59:1940-1944.

44 Louis ED, Applegate L, Graziano JH, et al. Interaction between blood lead concentration and delta-amino-levulinic acid dehydratase gene polymorphisms increases the odds of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2005;20:1170-1177.

45 Deuschl G, Elble RJ. The pathophysiology of essential tremor. Neurology. 2000;54:S14-S20.

46 Raethjen J, Deuschl G. Pathophysiology of essential tremor. In: Lyons KE, Pahwa R, editors. Handbook of Essential Tremor and Other Tremor Disorders. Boca Raton, FL: Taylor & Francis; 2005:27-50.

47 Raethjen J, Lindemann M, Schmaljohann H, et al. Multiple oscillators are causing parkinsonian and essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2000;15:84-94.

48 Findley LJ. The pharmacological management of essential tremor. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1986;9(Suppl 2):S61-S75.

49 Winkler GF, Young RR. The control of essential tremor by propranolol. Trans Am Neurol Assoc. 1971;96:66-68.

50 Koller WC. Long-acting propranolol in essential tremor. Neurology. 1985;35:108-110.

51 Meert TF. Pharmacological evaluation of alcohol withdrawal-induced inhibition of exploratory behaviour and supersensitivity to harmine-induced tremor. Alcohol Alcohol. 1994;29:91-102.

52 Findley LJ, Cleeves L, Calzetti S. Primidone in essential tremor of the hands and head: a double blind controlled clinical study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1985;48:911-915.

53 Lee KS, Kim JS, Kim JW, et al. A multicenter randomized crossover multiple-dose comparison study of arotinolol and propranolol in essential tremor. Parkinsonism Relat Disord. 2003;9:341-347.

54 Gironell A, Kulisevsky J, Barbanoj M, et al. A randomized placebo-controlled comparative trial of gabapentin and propranolol in essential tremor. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:475-480.

55 Pahwa R, Lyons K, Hubble JP, et al. Double-blind controlled trial of gabapentin in essential tremor. Mov Disord. 1998;13:465-467.

56 Connor GS. A double-blind placebo-controlled trial of topiramate treatment for essential tremor. Neurology. 2002;59:132-134.

57 Bushara KO, Malik T, Exconde RE. The effect of levetiracetam on essential tremor. Neurology. 2005;64:1078-1080.

58 Sullivan KL, Hauser RA, Zesiewicz TA. Levetiracetam for the treatment of essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2005.

59 Busenbark K, Pahwa R, Hubble J, et al. Double-blind controlled study of methazolamide in the treatment of essential tremor. Neurology. 1993;43:1045-1047.

60 Huber SJ, Paulson GW. Efficacy of alprazolam for essential tremor. Neurology. 1988;38:241-243.

61 Biary N, Koller W. Kinetic predominant essential tremor: successful treatment with clonazepam. Neurology. 1987;37:471-474.

62 Thompson C, Lang A, Parkes JD, et al. A double-blind trial of clonazepam in benign essential tremor. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1984;7:83-88.

63 Brin MF, Lyons KE, Doucette J, et al. A randomized, double masked, controlled trial of botulinum toxin type A in essential hand tremor. Neurology. 2001;56:1523-1528.

64 Kolek M, Mrozek V, Schenk P. [Cardiac manifestations of Friedreich’s ataxia]. Cas Lek Cesk. 2004;143:48-51.

65 Koller W, Pahwa R, Busenbark K, et al. High-frequency unilateral thalamic stimulation in the treatment of essential and parkinsonian tremor. Ann Neurol. 1997;42:292-299.

66 Limousin P, Speelman JD, Gielen F, et al. Multicentre European study of thalamic stimulation in parkinsonian and essential tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:289-296.

67 Pahwa R, Lyons KL, Wilkinson SB, et al. Bilateral thalamic stimulation for the treatment of essential tremor. Neurology. 1999;53:1447-1450.

68 Schuurman PR, Bosch DA, Bossuyt PM, et al. A comparison of continuous thalamic stimulation and thalamotomy for suppression of severe tremor. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:461-468.

69 Ohye C, Shibazaki T, Sato S. Gamma knife thalamotomy for movement disorders: evaluation of the thalamic lesion and clinical results. J Neurosurg. 2005;102(Suppl):234-240.

70 Siderowf A, Gollump SM, Stern MB, et al. Emergence of complex, involuntary movements after gamma knife radiosurgery for essential tremor. Mov Disord. 2001;16:965-967.

71 Young RF, Jacques S, Mark R, et al. Gamma knife thalamotomy for treatment of tremor: long-term results. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(Suppl 3):128-135.

72 Calzetti S, Sasso E, Negrotti A, et al. Effect of propranolol in head tremor: quantitative study following single-dose and sustained drug administration. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1992;15:470-476.

73 Massey EW, Paulson GW. Essential vocal tremor: clinical characteristics and response to therapy. South Med J. 1985;78:316-317.

74 Pahwa R, Busenbark K, Swanson-Hyland EF, et al. Botulinum toxin treatment of essential head tremor. Neurology. 1995;45:822-824.

75 Koller WC, Lyons KE, Wilkinson SB, et al. Efficacy of unilateral deep brain stimulation of the VIM nucleus of the thalamus for essential head tremor. Mov Disord. 1999;14:847-850.

76 Ondo W, Almaguer M, Jankovic J, et al. Thalamic deep brain stimulation: comparison between unilateral and bilateral placement. Arch Neurol. 2001;58:218-222.

77 Pollak P, Benabid AL, Gervason CL, et al. Long-term effects of chronic stimulation of the ventral intermediate thalamic nucleus in different types of tremor. Adv Neurol. 1993;60:408-413.

78 Zesiewicz TA, Elble R, Louis ED, et al. Practice parameter: therapies for essential tremor: report of the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology. 2005;64:2008-2020.

79 Heilman KM. Orthostatic tremor. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:880-881.

80 Pazzaglia P, Sabattini L, Lugaresi E. [On an unusual disorder of erect standing position (observation of 3 cases)]. Riv Sper Freniatr Med Leg Alien Ment. 1970;94:450-457.

81 Gerschlager W, Munchau A, Katzenschlager R, et al. Natural history and syndromic associations of orthostatic tremor: a review of 41 patients. Mov Disord. 2004;19:788-795.

82 Katzenschlager R, Costa D, Gerschlager W, et al. [123I]-FP-CIT-SPECT demonstrates dopaminergic deficit in orthostatic tremor. Ann Neurol. 2003;53:489-496.

83 Deuschl G, Lucking CH, Quintern J. [Orthostatic tremor: clinical aspects, pathophysiology and therapy]. EEG EMG Z Elektroenzephalogr Elektromyogr Verwandte Geb. 1987;18:13-19.

84 McManis PG, Sharbrough FW. Orthostatic tremor: clinical and electrophysiologic characteristics. Muscle Nerve. 1993;16:1254-1260.

85 Thompson PD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, et al. The physiology of orthostatic tremor. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:584-587.

86 Boroojerdi B, Ferbert A, Foltys H, et al. Evidence for a non-orthostatic origin of orthostatic tremor. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:284-288.

87 McAuley JH, Britton TC, Rothwell JC, et al. The timing of primary orthostatic tremor bursts has a task-specific plasticity. Brain. 2000;123(Pt 2):254-266.

88 Britton TC, Thompson PD. Primary orthostatic tremor. BMJ. 1995;310:143-144.

89 Wu YR, Ashby P, Lang AE. Orthostatic tremor arises from an oscillator in the posterior fossa. Mov Disord. 2001;16:272-279.

90 Poersch M. Orthostatic tremor: combined treatment with primidone and clonazepam. Mov Disord. 1994;9:467.

91 Wills AJ, Brusa L, Wang HC, et al. Levodopa may improve orthostatic tremor: case report and trial of treatment. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66:681-684.

92 Evidente VG, Adler CH, Caviness JN, et al. Effective treatment of orthostatic tremor with gabapentin. Mov Disord. 1998;13:829-831.

93 Onofrj M, Thomas A, Paci C, et al. Gabapentin in orthostatic tremor: results of a double-blind crossover with placebo in four patients. Neurology. 1998;51:880-882.

94 Rodrigues JP, Edwards DJ, Walters SE, et al. Gabapentin can improve postural stability and quality of life in primary orthostatic tremor. Mov Disord. 2005.

95 Koller WC, Vetere-Overfield B, Barter R. Tremors in early Parkinson’s disease. Clin Neuropharmacol. 1989;12:293-297.

96 Jankovic J, McDermott M, Carter J, et al. Variable expression of Parkinson’s disease: a base-line analysis of the DATATOP cohort. The Parkinson Study Group. Neurology. 1990;40:1529-1534.

97 Louis ED, Tang MX, Cote L, et al. Progression of parkinsonian signs in Parkinson disease. Arch Neurol. 1999;56:334-337.

98 Brooks DJ. PET and SPECT studies in Parkinson’s disease. Baillieres Clin Neurol. 1997;6:69-87.

99 Leenders KL, Oertel WH. Parkinson’s disease: clinical signs and symptoms, neural mechanisms, positron emission tomography, and therapeutic interventions. Neural Plast. 2001;8:99-110.

100 Tissingh G, Bergmans P, Booij J, et al. Drug-naive patients with Parkinson’s disease in Hoehn and Yahr stages I and II show a bilateral decrease in striatal dopamine transporters as revealed by [123I]beta-CIT SPECT. J Neurol. 1998;245:14-20.

101 Hirsch EC, Mouatt A, Faucheux B, et al. Dopamine, tremor, and Parkinson’s disease. Lancet. 1992;340:125-126.

102 Jellinger KA. Post mortem studies in Parkinson’s disease—is it possible to detect brain areas for specific symptoms? J Neural Transm Suppl. 1999;56:1-29.

103 Paulus W, Jellinger K. The neuropathologic basis of different clinical subgroups of Parkinson’s disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 1991;50:743-755.

104 Brooks DJ, Playford ED, Ibanez V, et al. Isolated tremor and disruption of the nigrostriatal dopaminergic system: an 18F-dopa PET study. Neurology. 1992;42:1554-1560.

105 Ghaemi M, Raethjen J, Hilker R, et al. Monosymptomatic resting tremor and Parkinson’s disease: a multitracer positron emission tomographic study. Mov Disord. 2002;17:782-788.

106 Doder M, Rabiner EA, Turjanski N, et al. Tremor in Parkinson’s disease and serotonergic dysfunction: an 11C-WAY 100635 PET study. Neurology. 2003;60:601-605.

107 Bergman H, Deuschl G. Pathophysiology of Parkinson’s disease: from clinical neurology to basic neuroscience and back. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl 3):S28-S40.

108 Bergman H, Raz A, Feingold A, et al. Physiology of MPTP tremor. Mov Disord. 1998;13(Suppl 3):29-34.

109 Hurtado JM, Rubchinsky LL, Sigvardt KA, et al. Temporal evolution of oscillations and synchrony in GPi/muscle pairs in Parkinson’s disease. J Neurophysiol. 2005;93:1569-1584.

110 Pogarell O, Gasser T, van Hilten JJ, et al. Pramipexole in patients with Parkinson’s disease and marked drug resistant tremor: a randomised, double blind, placebo controlled multicentre study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;72:713-720.

111 Cantello R, Riccio A, Gilli M, et al. Bornaprine vs placebo in Parkinson disease: double-blind controlled crossover trial in 30 patients. Ital J Neurol Sci. 1986;7:139-143.

112 Piccirilli M, D’Alessandro P, Testa A, et al. [Bornaprine in the treatment of parkinsonian tremor]. Rev Neurol. 1985;55:38-45.

113 Koller WC. Pharmacologic treatment of parkinsonian tremor. Arch Neurol. 1986;43:126-127.

114 Perry EK, Kilford L, Lees AJ, et al. Increased Alzheimer pathology in Parkinson’s disease related to antimuscarinic drugs. Ann Neurol. 2003;54:235-238.

115 Fischer PA, Baas H, Hefner R. Treatment of parkinsonian tremor with clozapine. J Neural Transm Park Dis Dement Sect. 1990;2:233-238.

116 Pakkenberg H, Pakkenberg B. Clozapine in the treatment of tremor. Acta Neurol Scand. 1986;73:295-297.

117 Jansen EN. Clozapine in the treatment of tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Acta Neurol Scand. 1994;89:262-265.

118 Krack P, Benazzouz A, Pollak P, et al. Treatment of tremor in Parkinson’s disease by subthalamic nucleus stimulation. Mov Disord. 1998;13:907-914.

119 Sturman MM, Vaillancourt DE, Metman LV, et al. Effects of subthalamic nucleus stimulation and medication on resting and postural tremor in Parkinson’s disease. Brain. 2004;127:2131-2143.

120 Deuschl G. Dystonic tremor. Rev Neurol (Paris). 2003;159:900-905.

121 Rivest J, Marsden CD. Trunk and head tremor as isolated manifestations of dystonia. Mov Disord. 1990;5:60-65.

122 Munchau A, Schrag A, Chuang C, et al. Arm tremor in cervical dystonia differs from essential tremor and can be classified by onset age and spread of symptoms. Brain. 2001;124:1765-1776.

123 Ferraz HB, De Andrade LA, Silva SM, et al. [Postural tremor and dystonia. Clinical aspects and physiopathological considerations]. Arq Neuropsiquiatr. 1994;52:466-470.

124 Bartolome FM, Fanjul S, Cantarero S, et al. [Primary focal dystonia: descriptive study of 205 patients]. Neurologia. 2003;18:59-65.

125 Shukla G, Behari M. A clinical study of non-parkinsonian and noncerebellar tremor at a specialty movement disorders clinic. Neurol India. 2004;52:200-202.

126 Jedynak CP, Bonnet AM, Agid Y. Tremor and idiopathic dystonia. Mov Disord. 1991;6:230-236.

127 Marsden CD. Dystonia: the spectrum of the disease. Res Publ Assoc Res Nerv Ment Dis. 1976;55:351-367.

128 Vidailhet M, Jedynak CP, Pollak P, et al. Pathology of symptomatic tremors. Mov Disord. 1998;13(Suppl 3):49-54.

129 Masuhr F, Wissel J, Muller J, et al. Quantification of sensory trick impact on tremor amplitude and frequency in 60 patients with head tremor. Mov Disord. 2000;15:960-964.

130 Jankovic J, Schwartz K. Botulinum toxin treatment of tremors. Neurology. 1991;41:1185-1188.

131 Coubes P, Roubertie A, Vayssiere N, et al. Treatment of DYT1-generalised dystonia by stimulation of the internal globus pallidus. Lancet. 2000;355:2220-2221.

132 Alusi SH, Worthington J, Glickman S, et al. A study of tremor in multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2001;124:720-730.

133 Louis ED, Lynch T, Ford B, et al. Delayed-onset cerebellar syndrome. Arch Neurol. 1996;53:450-454.

134 Neiman J, Lang AE, Fornazzari L, et al. Movement disorders in alcoholism: a review. Neurology. 1990;40:741-746.

135 Flament D, Hore J. Movement and electromyographic disorders associated with cerebellar dysmetria. J Neurophysiol. 1986;55:1221-1233.

136 Flament D, Hore J. Comparison of cerebellar intention tremor under isotonic and isometric conditions. Brain Res. 1988;439:179-186.

137 Hore J, Flament D. Evidence that a disordered servo-like mechanism contributes to tremor in movements during cerebellar dysfunction. J Neurophysiol. 1986;56:123-136.

138 Hallett M, Shahani BT, Young RR. EMG analysis of patients with cerebellar deficits. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1975;38:1163-1169.

139 Mauritz KH, Schmitt C, Dichgans J. Delayed and enhanced long latency reflexes as the possible cause of postural tremor in late cerebellar atrophy. Brain. 1981;104:97-116.

140 Hallett M, Ravits J, Dubinsky RM, et al. A double-blind trial of isoniazid for essential tremor and other action tremors. Mov Disord. 1991;6:253-256.

141 Rascol A, Clanet M, Montastruc JL, et al. L5H tryptophan in the cerebellar syndrome treatment. Biomedicine. 1981;35:112-113.

142 Trouillas P, Xie J, Getenet JC, et al. [Effect of buspirone, a serotonergic 5-HT-1A agonist in cerebellar ataxia: a pilot study. Preliminary communication]. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1995;151:708-713.

143 Fox P, Bain PG, Glickman S, et al. The effect of cannabis on tremor in patients with multiple sclerosis. Neurology. 2004;62:1105-1109.

144 Alusi SH, Aziz TZ, Glickman S, et al. Stereotactic lesional surgery for the treatment of tremor in multiple sclerosis: a prospective case-controlled study. Brain. 2001;124:1576-1589.

145 Lozano AM. VIM thalamic stimulation for tremor. Arch Med Res. 2000;31:266-269.

146 Masucci EF, Kurtzke JF, Saini N. Myorhythmia: a widespread movement disorder. Clinicopathological correlations. Brain. 1984;107:53-79.

147 Remy P, de Recondo A, Defer G, et al. Peduncular ‘rubral’ tremor and dopaminergic denervation: a PET study [see comments]. Neurology. 1995;45:472-477.

148 Deuschl G, Wilms H, Krack P, et al. Function of the cerebellum in Parkinsonian rest tremor and Holmes’ tremor. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:126-128.

149 Krack P, Deuschl G, Kaps M, et al. Delayed onset of “rubral tremor” 23 years after brainstem trauma. Mov Disord. 1994;9:240-242.

150 Miwa H, Hatori K, Kondo T, et al. Thalamic tremor: case reports and implications of the tremor-generating mechanism. Neurology. 1996;46:75-79.

151 Kim JS. Delayed onset mixed involuntary movements after thalamic stroke: clinical, radiological and pathophysiological findings. Brain. 2001;124:299-309.

152 Lehericy S, Grand S, Pollak P, et al. Clinical characteristics and topography of lesions in movement disorders due to thalamic lesions. Neurology. 2001;57:1055-1066.

153 Kim MC, Son BC, Miyagi Y, et al. Vim thalamotomy for Holmes’ tremor secondary to midbrain tumour. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2002;73:453-455.

154 Kudo M, Goto S, Nishikawa S, et al. Bilateral thalamic stimulation for Holmes’ tremor caused by unilateral brainstem lesion. Mov Disord. 2001;16:170-174.

155 Nikkhah G, Prokop T, Hellwig B, et al. Deep brain stimulation of the nucleus ventralis intermedius for Holmes (rubral) tremor and associated dystonia caused by upper brainstem lesions. Report of two cases. J Neurosurg. 2004;100:1079-1083.

156 Lapresle J. Palatal myoclonus. Adv Neurol. 1986;43:265-273.

157 Deuschl G, Mischke G, Schenck E, et al. Symptomatic and essential rhythmic palatal myoclonus. Brain. 1990;113:1645-1672.

158 Deuschl G, Toro C, Valls SJ, et al. Symptomatic and essential palatal tremor. 1. Clinical, physiological and MRI analysis. Brain. 1994:775-788.

159 Deuschl G, Wilms H. Clinical spectrum and physiology of palatal tremor. Mov Disord. 2002;17(Suppl 2):S63-S66.

160 Samuel M, Torun N, Tuite PJ, et al. Progressive ataxia and palatal tremor (PAPT): clinical and MRI assessment with review of palatal tremors. Brain. 2004;127:1252-1268.

161 Deuschl G, Jost S, Schumacher M. Symptomatic palatal tremor is associated with signs of cerebellar dysfunction. J Neurol. 1996;243:553-556.

162 Deuschl G, Toro C, Hallett M. Symptomatic and essential palatal tremor. 2. Differences of palatal movements. Mov Disord. 1994;9:676-678.

163 Llinas R, Volkind RA. The olivocerebellar system: functional properties as revealed by harmaline-induced tremor. Exp Brain Res. 1973;18:69-87.

164 Elble RJ. Inhibition of forearm EMG by palatal myoclonus. Mov Disord. 1991;6:324-329.

165 Leigh RJ, Averbuch HL, Tomsak RL, et al. Treatment of abnormal eye movements that impair vision: strategies based on current concepts of physiology and pharmacology. Ann Neurol. 1994;36:129-141.

166 Repka MX, Savino PJ, Reinecke RD. Treatment of acquired nystagmus with botulinum neurotoxin A. Arch Ophthalmol. 1994;112:1320-1324.

167 Bakheit AM, Behan PO. Palatal myoclonus successfully treated with clonazepam [letter] [see comments]. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1990:53.

168 Jabbari B, Scherokman B, Gunderson CH, et al. Treatment of movement disorders with trihexyphenidyl. Mov Disord. 1989;4:202-212.

169 Borggreve F, Hageman G. A case of idiopathic palatal myoclonus: treatment with sodium valproate. Eur Neurol. 1991;31:403-404.

170 Cakmur R, Idiman E, Idiman F, et al. Essential palatal tremor successfully treated with flunarizine. Eur Neurol. 1997;38:133-134.

171 Gambardella A, Quattrone A. Treatment of palatal myoclonus with sumatriptan [letter]. Mov Disord. 1998;13:195.

172 Scott BL, Evans RW, Jankovic J. Treatment of palatal myoclonus with sumatriptan. Mov Disord. 1996;11:748-751.

173 Pakiam AS, Lang AE. Essential palatal tremor: evidence of heterogeneity based on clinical features and response to Sumatriptan. Mov Disord. 1999;14:179-180.

174 Deuschl G, Lohle E, Heinen F, et al. Ear click in palatal tremor: its origin and treatment with botulinum toxin. Neurology. 1991;41:1677-1679.

175 Yeung KB, Thomas PK, King RH, et al. The clinical spectrum of peripheral neuropathies associated with benign monoclonal IgM, IgG and IgA paraproteinaemia. Comparative clinical, immunological and nerve biopsy findings. J Neurol. 1991;238:383-391.

176 Busby M, Donaghy M. Chronic dysimmune neuropathy. A subclassification based upon the clinical features of 102 patients. J Neurol. 2003;250:714-724.

177 Cardoso F, Jankovic J. Movement disorders. Neurol Clin. 1993;11:625-638.

178 Dalakas MC, Teravainen H, Engel WK. Tremor as a feature of chronic relapsing and dysgammaglobulinemic polyneuropathies. Incidence and management. Arch Neurol. 1984;41:711-714.

179 Bain PG, Britton TC, Jenkins IH, et al. Tremor associated with benign IgM paraproteinaemic neuropathy. Brain. 1996;119:789-799.

180 Plante-Bordeneuve V, Guiochon-Mantel A, Lacroix C, et al. The Roussy-Lévy family: from the original description to the gene. Ann Neurol. 1999;46:770-773.

181 Ruzicka E, Jech R, Zarubova K, et al. VIM thalamic stimulation for tremor in a patient with IgM paraproteinaemic demyelinating neuropathy. Mov Disord. 2003;18:1192-1195.

182 Kim YJ, Pakiam AS, Lang AE. Historical and clinical features of psychogenic tremor: a review of 70 cases. Can J Neurol Sci. 1999;26:190-195.

183 Deuschl G, Koster B, Lucking CH, et al. Diagnostic and pathophysiological aspects of psychogenic tremors. Mov Disord. 1998;13:294-302.

184 Factor SA, Podskalny GD, Molho ES. Psychogenic movement disorders: frequency, clinical profile, and characteristics. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;59:406-412.

185 Brown P, Thompson PD. Electrophysiological aids to the diagnosis of psychogenic jerks, spasms, and tremor. Mov Disord. 2001;16:595-599.

186 McAuley JH, Rothwell JC, Marsden CD, et al. Electrophysiological aids in distinguishing organic from psychogenic tremor. Neurology. 1998;50:1882-1884.

187 Lauk M, Koster B, Timmer J, et al. Side-to-side correlation of muscle activity in physiological and pathological human tremors. Clin Neurophysiol. 1999;110:1774-1783.

188 Raethjen J, Kopper F, Govindan RB, et al. Two different pathogenetic mechanisms in psychogenic tremor. Neurology. 2004;63:812-815.

189 McAuley J, Rothwell J. Identification of psychogenic, dystonic, and other organic tremors by a coherence entrainment test. Mov Disord. 2004;19:253-267.