Chapter 20 Treatment of Venous Ulcers

In this chapter, the etiology is examined from a hemodynamic and cellular aspect. Adjunctive treatments, both medical and surgical, are discussed. Finally, a new treatment option—terminal interruption of the reflux source (TIRS)—is introduced. First, all venous ulcers have a common denominator. The commonality is increased ambulatory venous pressure. A pressure above 45 mm Hg increases the risk of ulceration. The higher the pressure, the greater is the risk of eventual venous ulceration.1 The increased pressure may be due solely to reflux at some point in the venous system or coexist with other factors.2

Compression therapy with either elastic or inelastic dressings has been the historical treatment.3,4 As compliance increases, so do the healing rates. However, with compression alone, there is still a high recurrence rate.4,5

Other adjuncts to improving ulcer healing have been described. Medical therapy has included rutosides, aspirin, and pentoxifylline.6–8 Of course, local wound care is essential and irrigation and debridement of devitalized tissue are essential.

Skin grafts have been used as an adjunct in wound healing for venous ulcers. These grafts include full-thickness punch grafts, xenografts, or allografts. To date, in an updated review on skin grafting for venous ulcers, bilayer artificial skin used in association with compression dressings increased ulcer healing compared to compression alone.9,10 In the study by Falanga et al.,9 healing at 6 months was only 63% with allogenic human skin equivalent compared to 43% with compression alone.9

Surgical techniques such as stripping the great saphenous vein,10,11 subfascial perforator ligation,12,13 endoluminal thermal ablation,14 and minimally invasive perforator therapy15 have been used as adjuncts in the treatment of venous ulcers. Nontargeted foam sclerotherapy has also been mentioned as a treatment modality.15–17 Except for foam sclerotherapy, none of these procedures has proved to increase the healing rate of venous ulcers. These adjunctive procedures are mostly directed at preventing future occurrences.

Recently, the TIRS technique was introduced.18 The TIRS technique targets only those vessels in close proximity to the venous ulcer.

When using the TIRS technique, patients at Midwest Vein and Laser Center had rapid healing of ulcers compared to compression alone or compression with other adjunctive procedures. In a series of 20 patients treated with the TIRS technique, healing occurred in 90% of patients within 8 weeks. All patients had been compliant with compression for 18 to 24 months prior to treatment.18

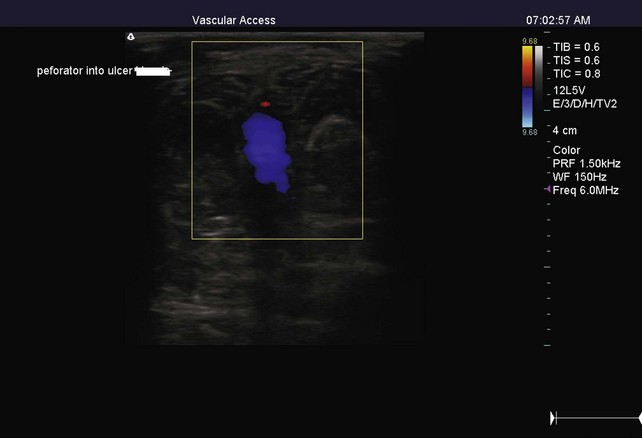

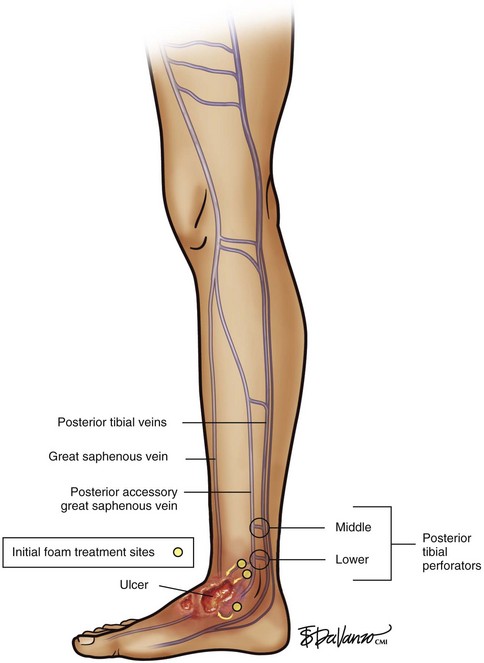

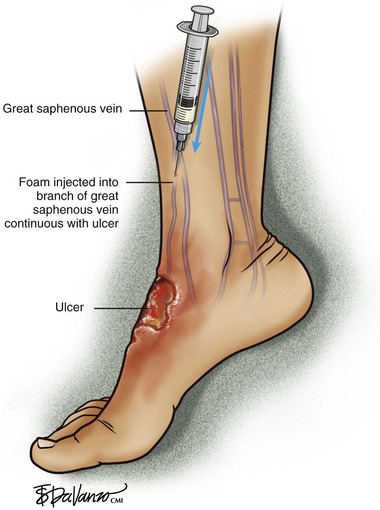

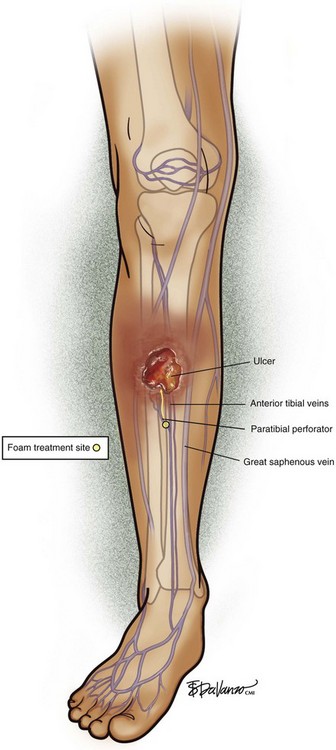

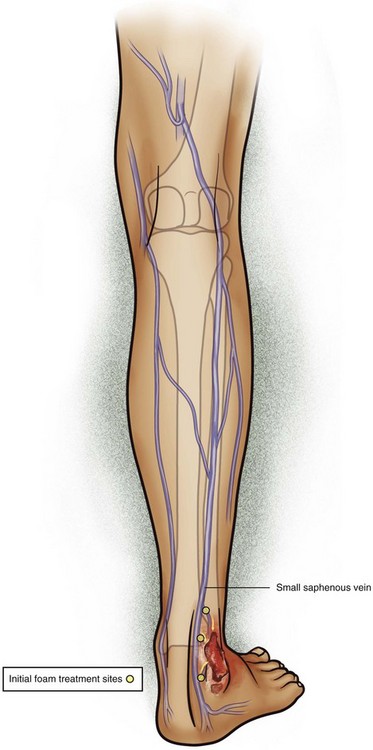

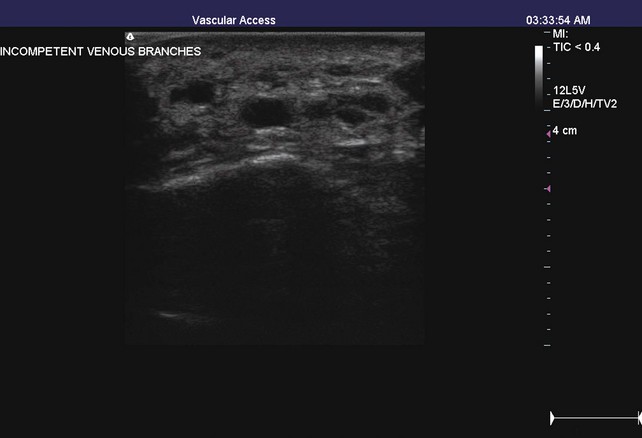

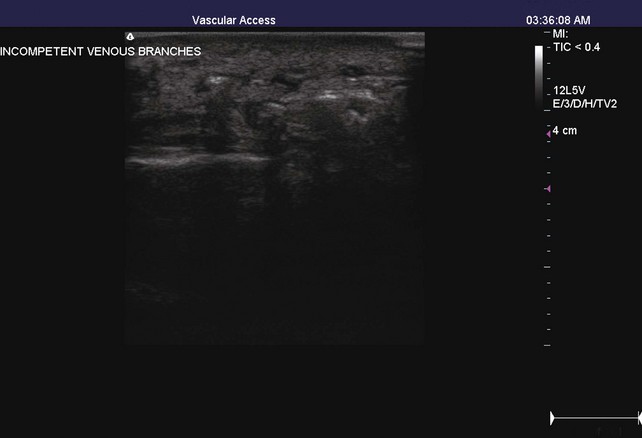

The TIRS technique requires good interpretive ultrasound skills and the ability to safely deliver the foamed sclerotherapy with the aid of ultrasound guidance. Only the most distal venous branches draining the area of the ulcer are identified. In some patients, especially those with anterior calf ulcers, a perforator leading directly to the ulcer bed may be identified (Figs. 20-1 and 20-2). The proximal source of reflux (i.e., saphenous vein, classic posterior tibial perforator, or other source proximally) is ignored. Only the distal vessel or vessels are targeted initially (Fig. 20-3 through 20-13).

Using ultrasound guidance, these vessels are cannulated with needle penetration through normal skin, as far from the ulcer margin as possible. A 3-mL syringe and a 22-gauge needle are used in our clinic. Cannulation is performed superior to the ulcer if chronic skin change exists inferiorly. After penetrating the target vessel, the foam is slowly injected (Fig. 20-14). In our clinic, a 4 : 1 mixture of sodium tetradecyl sulfate (Sotradecol) and CO2 is used. After injection of the foamed solution, compression is applied and local wound care is performed. The patient is rescanned at weekly intervals and foam injections are repeated if necessary. A 1% concentration is used, unless extenuating circumstances such as concurrent anticoagulation or high flow exist. A 3% foamed solution of sodium tetradecyl sulfate is then used.

1 Payne S, London N, Newland C, et al. Ambulatory venous pressure: Correlation with skin condition and role in identifying surgically correctible disease. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg. 1996;11:195-200.

2 Raju S, Neglen P, Carr-White P, et al. Ambulatory venous hypertension: component analysis in 373 limbs. Vasc Endovascular Surg. 1999;33:257-266.

3 Fletcher A, Cullum N, Sheldon T. A systematic review of compression treatment for venous leg ulcers. BMJ. 1997;315:576-580.

4 Erickson C, Lanza D, Karp D, et al. Healing of venous ulcers in an ambulatory care program: the roles of chronic venous insufficiency and patient compliance. J Vasc Surg. 1995;22:629-636.

5 Scriven J, Taylor L, Wood A, et al. A prospective randomized trial of four-layer versus short stretch compression bandages for the treatment of venous leg ulcers. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1998;80:215-220.

6 Falanga V, Fujitani R, Diaz C, et al. Systemic treatment of venous leg ulcers with high doses of pentoxifylline: efficacy in a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Wound Repair Regen. 1999;7:208-213.

7 Colgan M, Dormandy J, Jones P, et al. Oxpentifylline treatment of venous ulcers of the leg. BMJ. 1990;300:972-975.

8 Gohel M, Davies A. Pharmacological agents in the treatment of venous disease: an update of the available evidence. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2009;7:303-308.

9 Falanga V, Margolis D, Alvarez O, et al. Rapid healing of venous ulcers and lack of clinical rejection with an allogeneic cultured human skin equivalent. Arch Dermatol. 1998;134:293-300.

10 Barwell J, Davies C, Deacon J, et al. Comparison of surgery and compression with compression alone in chronic venous ulceration (ESCHAR STUDY): randomized controlled trial. Lancet. 2008;363:1854-1859.

11 Homans J. The operative treatment of varicose veins and ulcers, based on classification of these lesions. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1916;22:143-158.

12 Pierik E, Van Urk H, Hop W, Wittens C. Endoscopic versus open subfascial division of incompetent perforating veins in the treatment of venous leg ulceration: a randomized trial. J Vasc Surg. 1997;26:1049-1054.

13 Glovicski P, Bergan J, Rhodes J, et al. Mid-term results of endoscopic perforator vein interruption for chronic venous insufficiency: lessons learned from the North American subfascial endoscopic perforator surgery registry. The North American Study Group. J Vasc Surg. 1999;29:489-502.

14 Rautio T, Ohinmaa A, Perala J, et al. Endovenous obliteration versus conventional stripping operation in the treatment of primary varicose veins: a randomized controlled trial with comparison of the costs. J Vasc Surg. 2002;35:958-965.

15 Poblete H, Elias S. Venous ulcers: New options in treatment: minimally invasive vein surgery. J Am Coll Cert Wound Special. 2009;1:12-19.

16 Hertzman P, Owens R. Rapid healing of chronic venous ulcers following ultrasound-guided foam sclerotherapy. Phlebology. 2007;22:34-39.

17 Cabrera J, Redondo P, Becerra A, et al. Ultrasound-guided injection of polidocanol microfoam in the management of venous leg ulcers. Arch Dermatol. 2004;140:667-673.

18 Bush R. New technique to heal venous ulcers: terminal interruption of the reflux source (TIRS). Perspect Vasc Surg Endovasc Ther. 2010;22:194-199.