Treatment of the lumbar spine

Introduction

A wide variety of non-surgical treatments are advocated in the management of low back pain. Back school instructions, bed rest, cryotherapy, medication, exercises, manipulation, traction, mobilization, local blocks, epidural infiltrations and spinal orthosis all claim to have their successes but until now, controlled studies of large, unselected populations have not demonstrated the superiority of any one of these measures,1–7 which thus supports the view that there seems to be no definite evidence that any treatment for low back pain is much better than the placebo effect.8,9 Some authors even suggest that the main effects of the therapies are produced not through the reversal of physical weaknesses targeted by the corresponding exercise method but rather through some ‘central’ effect, perhaps involving an adjustment of perception in relation to pain and disability.10

Obviously, these studies have reinforced therapeutic nihilism. As conservative measures are not proven to be effective, the patient is told to learn to live with the disability until it disappears spontaneously.11

However, in analysing the results, one striking factor emerges – the lack of a proper diagnosis. In current clinical trials on the effectiveness of treatment for lumbar disorders, the course of one symptom only (pain) is evaluated in randomized groups of patients. This is completely wrong. Controversies over treatment are usually the result of studies performed on widely differing lesions. A group of patients complaining of ‘backache’ is very heterogeneous. Even if, in most cases, the disc is responsible for the pain, the mechanism will differ considerably from patient to patient. Before any kind of randomization is done, the individual disorders in any group of patients should be clearly identified; treatment could then be given not for a symptom but for a well-defined condition.12 We therefore believe that, before treatment of any kind is instituted, a clear diagnosis must be made and the physician must have a distinct idea of the underlying cause. Treatment can then be prescribed selectively, according to the type and the severity of the lesion. For example, a recent systematic review of randomized clinical trials on spinal manipulation could find no evidence of effectiveness, except in some subgroups of patients, using clearly delineated clinical inclusion criteria.13

The history and clinical examination almost always indicate the best method of treatment for an individual patient. It is our personal experience that, if conservative treatment techniques are employed intelligently, there is definite evidence that in each case one treatment is better than another or than the placebo effect. Also, only a few patients will remain wholly unrelieved, in which case surgery may be required. Even when surgery is indicated, the decision must be made on clinical grounds alone. An abnormality seen on imaging and not confirmed by clinical examination is not an indication for surgery.14

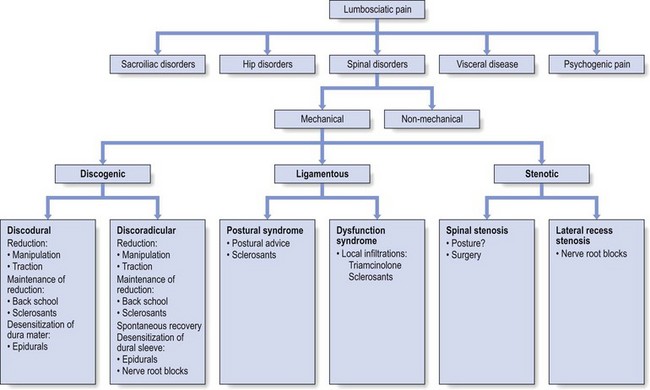

Is the pain caused by a spinal disorder?

It is important to exclude psychogenic pain and pain of visceral origin referred to the back.

If the spinal disorder is activity-related (mechanical), to which ‘concept’ does it belong?

Is the disorder a discodural or discoradicular interaction?

• Reduction of the displacement: achieved by manipulation or traction.

• Maintenance of reduction: obtained by sclerosing injections and/or back school instructions.

• Desensitization of the dura mater: acute or gross inflammation requires desensitization of the dura mater before manipulation or traction is attempted. Alternatively, if the dura mater remains inflamed after discodural contact has ceased, the treatment is epidural local anaesthesia.

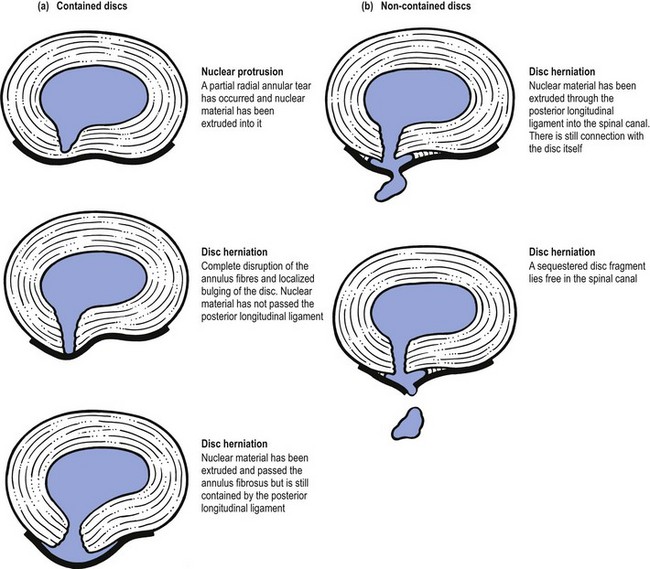

• Desensitization of the dural nerve root sleeve: in intense discoradicular contact leading to some degree of parenchymatous involvement, attempts at reduction fail. De-inflammation and desensitization of the dural sleeve, while spontaneous recovery is awaited, is then a good and defensible therapeutic approach. Epidural local anaesthesia via the sacral canal is the technique of choice. Should this fail, a sinuvertebral and nerve root block can be substituted. Desensitization of the dural sleeve is also recommended when the discoradicular contact has lasted for some time or when the nerve root remains inflamed after the conflict has ceased (Fig. 40.1).

What sort of person is the patient?

The following questions must be addressed when devising a treatment plan:

• What attitude does the patient have towards the problem?

• Is there a desire to get better?

• Is there any compensation claim?

• Is there evidence of psychoneurosis?

• Will active and sometimes unpleasant forms of treatment be tolerated?

These questions must be addressed when devising a treatment plan.

If treatment is employed along these lines, only a few patients will remain unrelieved. This approach has also proved to be safe and, at the same time, is a meaningful, realistic and practical response to the enormous liability of lumbar disorders in terms of cost and needless human suffering. In 1986, the annual cost of back pain in the USA approached $81 billion.15 By 1995, the total cost to society of low back pain was more than $100 billion16 and the economic loss 101.8 million workdays.17 In the UK, the direct healthcare cost of back pain in 1998 was estimated to be £1632 million. However, this figure is insignificant compared to the cost of the production losses related to it, which was £10 668 million, making back pain one of the most costly conditions for which an economic analysis has been carried out.18

A substantial portion of low back care costs reflects expensive surgical therapy, when many patients could have been effectively treated if the above-mentioned less costly regimens had been tried first. Unfortunately, the average spinal surgeon is usually neither trained in nor knowledgeable about conservative spinal therapy. In fact, in some of the present state healthcare systems, surgery is routinely performed in almost all cases of low back pain (Burton14: p. 105). This has been confirmed by Finneson,19 who studied one series of 94 patients in whom back surgery had failed and found that in 81% the original surgery was not indicated.

Manipulation

Introduction

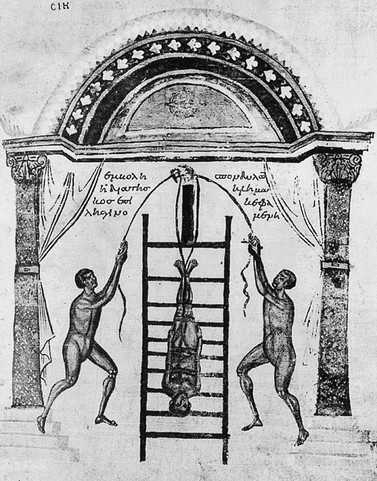

Manipulation and traction are no exceptions to the rule that all medicine can be traced back to Hippocrates (400 bc). His methods of treating back disorders were practised in the subsequent centuries by other famous physicians: for example, Apollonius, Galen, Avicenna, Ambroise Paré, Percival Pott, Sir James Paget and many others. In China, the technique of manipulation was fully established during the Tang Dynasty (ad 618–907). Illustrations show that the ancient methods of manipulation and apparatus traction did not differ very much from the methods of treatment practised nowadays in low back pain and sciatica (Fig. 40.2).

Manipulation and traction are methods of reducing pain and disability caused by internal derangement of intervertebral cartilaginous structures. This treatment undoubtedly stems from man’s experience with those examples of lumbago, low back pain and sciatica that were relieved by a sudden twist or a fall. Schiötz and Cyriax20 described several examples in which patients reported such a sudden relief of symptoms after an unintentional movement. One of our colleagues reported a patient who recovered from backache on falling down her basement cellar steps. Undoubtedly, such experiences have given rise to various, sometimes bizarre mechanical treatments in folk medicine, such as trampling on a patient’s back, wrestling the back, striking the back with the weight of a steel bar or standing back to back ‘weighing salt’ (two persons stand back to back, hooking their arms at the elbow; each person bends forwards in turn, lifting the other from the floor). These measures seem non-specific and possibly harmful but Schiötz commented: ‘It seems justified to infer that methods found effective by the natives of parts of the world as far apart as Norway, Mexico and the Pacific Islands over many, many centuries must be valid.’ These primitive methods are also the models for more modern techniques of manipulation and traction taught and practised by trained doctors and therapists all over the world.

Although different methods and different theoretical concepts developed, this seemed not to matter much as all claimed their successes. Cyriax21 was convinced that, in nearly all cases, a similar mechanism is at work – a dislocated fragment of disc returns to position or a protrusion is ‘sucked back’. He also stated: ‘Spinal manipulative methods of orthopaedic medicine are perfectly straightforward and possess an explicable intention directed to a factual lesion. They are based on the discovery of disc lesions as the primary cause of degenerative change and pain of spinal origin.’

It is hard to believe that, even nowadays, many doctors still refuse to recommend manipulation of the back as the treatment of choice in nearly all cases of acute low back pain and sciatica. Avoiding discussion of the topic of spinal manipulation is also unwise, since a significant number of their patients will have received or will be considering this form of treatment: in the USA in 1980, 120 million surgery visits were made to chiropractors.22

An increasing number of controlled clinical trials on well-delineated subgroups have been published, which compare the results of manipulation to different forms of placebo therapy as well as to other forms of conservative management.23–34 The positive effects of manipulation appear to occur either immediately after the manipulation session or within the first 4–6 weeks of treatment.35–37

Definition of manipulation

In orthopaedic medicine, spinal manipulation is defined as a method of conservative treatment by passive movements, carried out with a single thrust or sustained pressure, in order to return a displacement to its proper position (see Ch. 5, p. 95). During the thrust, an audible click is often produced. This may accompany immediate relief of symptoms and signs, which supports the precision of the diagnosis and selected therapy.

There are different schools of thought in manipulation, which derive from different attitudes towards spinal disorders. The theories on which manipulation is based include the reduction of disc protrusions,38,39 the correction of posterior joint dysfunction,40 the mobilization of blocked vertebral joints,41–44 the reduction of nerve root compression,45,46 the normalization of reflex activity47–50 and the relaxation of muscles.51

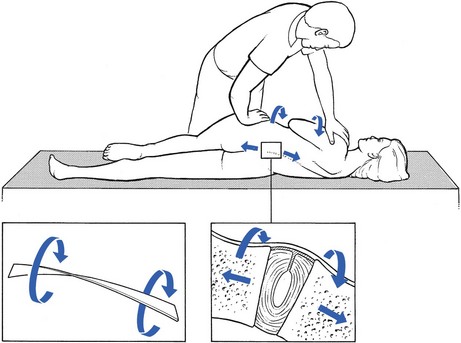

• The lumbar spine is positioned in such a way that the affected intervertebral joint opens, i.e. gives the loose fragment room to move.

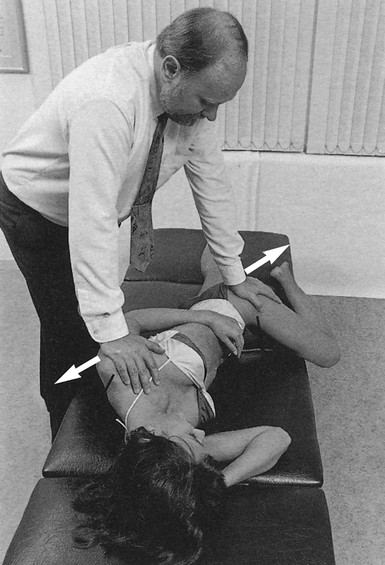

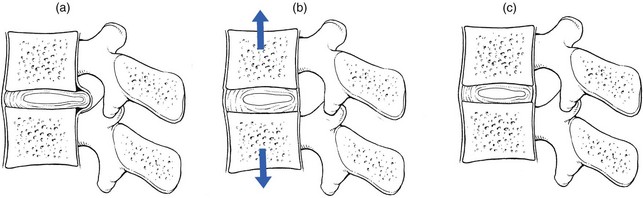

• The manipulation is usually carried out during traction. This tautens the posterior longitudinal ligament and causes suction in the disc, so exerting a centripetal force (Fig. 40.3).

Most other manipulative schools claim to work more selectively, i.e. on the affected level only. They claim to have developed the clinical skills to localize, by palpation, the exact site of the ‘fixation’ or ‘locking’. Several studies have failed, however, to demonstrate the reliability of this approach.52–57 We support McKenzie’s58 conclusion that demystification of spinal manipulative therapy is an urgent priority. Both chiropractice and osteopathy thrive by creating the impression that there is something complex and exclusive about the practice of passive end-range motion that only chiropractors or osteopaths can understand or have the skills to ‘feel’. They generate the belief that, in order to become skilled in the understanding and delivery of spinal manipulative therapy, it is necessary to undergo 3 or 4 years of training.59 This suggestion is undermined by the fact that the majority of lay manipulators in Britain have never had any tuition at all and yet have amassed many satisfied clients and also very rarely figure in actions for damages.20

• The displacement should be cartilaginous, not too large and not placed too far laterally. Soft nuclear protrusions are seldom reduced by manipulation unless they are small and very recent, and the technique of manipulation is changed to sustained pressure. If the consistency of the displacement is not quite clear, with symptoms and signs pointing in opposite directions, it is worthwhile making one attempt at manipulation. During the first session, it is usually quickly apparent whether reduction by this means will prove feasible or not. If it fails, traction is substituted the next day. Reduction of cartilage displacements, together with full relief of symptoms and signs, has proved to be possible in two-thirds of all cases of backache and in one-third of all cases of sciatica.60 Just about half of all lumbago cases are relieved in one treatment.61,62

• The patient must be mentally stable and keen to get well. If this psychogenic aspect is neglected, on some occasions a patient may be treated who claims to have been made worse by a type of therapy that is regarded in retrospect as unacceptable. Hence it is important to avoid these active methods of treatment when the patient’s attitude appears to be more important than the minor mechanical disorder found on examination.

Indications for manipulation

History and clinical examination almost always supply sufficient information to select those cases suited to manipulation (see Box 40.3, below).

Acute annular lumbago

Reduction should always be attempted, except in hyperacute cases where the attempt proves impossible to bear. An epidural injection is then substituted and followed by manipulation the next day. If such an injection is refused, it is still possible for the patient to recover in about a fortnight with bed rest and the use of McKenzie’s extension mobilizations58 and anti-deviation techniques. The moment the process has ceased to be hyperacute, treatment by manipulation can be tried again.

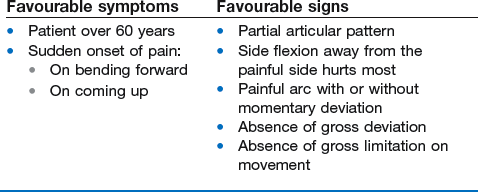

Backache

• A partial articular pattern in which some movements are only painful at extreme range: for example, flexion, extension and side flexion away from the painful side

• The existence of a painful arc with or without momentary deviation

• Absence of gross deviation caused by muscle spasm on standing or during as much flexion as the patient can tolerate

• Absence of gross limitation on movement – gross deviation or limitation of movement always requires several sessions of manipulation (Box 40.1).

Contraindications

These may be divided into circumstances in which manipulation is absolutely contraindicated and those in which manipulation is of no use, although not harmful to the patient (Box 40.3). Appropriate selection of patients and choice of techniques can avoid such serious complications as have been reported.63,64

Absolute contraindications

Danger to the fourth sacral roots65,66

Acute lumbago and bilateral sciatica with compression of the nerve roots at the same level are examples of a large central protrusion in which bulging of the posterior longitudinal ligament is to be expected. Such a protrusion may also cause spinal claudication. These patients have symptoms during walking, immediately relieved by lying down.67

Anticoagulant medication

Manipulation of patients on anticoagulant therapy may lead to an intraspinal haematoma.68 A patient who has a clotting abnormality should also not be subjected to forceful manipulations.

Final month of pregnancy

Manipulation should not be employed at any time if there is any predisposition to miscarriage.

Cases in which manipulation is not useful

Too large a protrusion

Protrusions causing impaired root conduction

All such protrusions are impossible to reduce by either manipulation or traction. If clinical signs of muscle weakness, cutaneous analgesia or reflex disturbances are present, the protrusion is too large (and located too far laterally) to be replaced.38,69–73 Epidural local anaesthesia is the treatment of choice.

Too soft a protrusion

Acute nuclear lumbago is also an example of a protrusion that is too soft to manipulate with a thrust. The history is of pain that began gradually, after much stooping and lifting, and became slowly worse over the next few hours. The following morning, the patient wakes unable to get out of bed because of severe lumbar pain. The patient is always under 60 years old and, although manipulation is indicated, it must be exerted by sustained pressure. If this makes the patient better, techniques should follow in the supine, side-lying and standing positions to correct a persisting lateral deviated position of the trunk (see pp. 554–556).

Alternatively, an epidural injection can be tried, again followed the next day by manœuvres to correct a lateral deformity. However, if these measures all fail, constant pelvic traction, in a supine position and continued for some days, is called for, slowly changed to periodic half an hour daily traction. Extension mobilizations, as recommended by McKenzie,58 have also been found to be effective; this treatment is based on McKenzie’s hypothesis that flow or displacement of fluid, nucleus or sequestrum can occur within the intact annulus of the intervertebral disc as a result of prolonged or repetitive loading. This most commonly occurs with flexion loading. He recommends well-defined extension forces in order to reverse the direction of flow or displacement.

Compression phenomena

Central stenosis, lateral recess stenosis and the ‘self-reducing’ disc protrusion do not respond to manipulative treatment. In stenosis, the underlying condition is the reason that attempted manipulation or traction fails.71,74,75 The self-reducing disc protrusion, with symptoms at the end of the day only, may be reduced by manipulation but will prove to be transient anyway.38

Dangers of manipulation

Lumbar manipulation is quite safe.63,64 The most frequently reported serious complication is further prolapse of a herniated disc, resulting in a cauda equina syndrome. However, the risk of spinal manipulation causing a cauda equina syndrome is estimated to be less than 1 per 3.7 million treatments.65,76 Most of the incidents were described in patients undergoing manipulation under anaesthesia or chiropractic adjustments.66 Long-lever, high-force rotation techniques in the side-lying position are regarded as responsible. This is only partly true: the underlying cause is the lack of adequate examination to rule out unsuitable disorders. If, in contrast, manipulative procedures are instituted after a thorough examination, those described in this book have never led to severe accidents. The main advantages of these manipulations are:

• A great deal of traction is used to exert a strong centripetal force on the intervertebral joint.

• Movements towards flexion, which can intensify potentially harmful centrifugal forces, are excluded.

• Each manœuvre is followed by a fresh assessment of dural, root and articular signs, which affords a clear pointer to what has happened inside the joint and what the next step should be.

Results

Acute lumbago

If there is no deviation on standing or in the maximal forward-bent position and the lumbago is of recent onset, 50% of patients will get well with one treatment.61,62 Potter73 noted that 93% of such patients either fully recovered or were much improved following manipulation.

Backache

Manipulation either works fast and leads to a swift disappearance of symptoms and signs, or has no effect at all. If there is no clear improvement after one or two sessions, this treatment form should be abandoned. Uncomplicated low back pain of recent onset seems to be significantly more responsive to manipulation than are chronic cases.29,73,74,77,78 The beneficial effect of manipulation is particularly significant in low back pain with dural signs.79

Sciatica

The success rate of manipulation in an uncomplicated discoradicular conflict is about 1 in 3 (J. Cyriax: personal communication, 1982). This result was confirmed by one report that claimed complete recovery in 18 out of 50 chronic cases with unilateral sciatica after one manipulative session.60 Others found that 25–75% of their patients with uncomplicated sciatica recovered or improved considerably after spinal manipulations.39,62,70,73,79

Manipulation techniques

The manipulative techniques used in orthopaedic medicine can be divided into three groups:

Rotation techniques

Five different rotation techniques are described, all of which are used frequently.

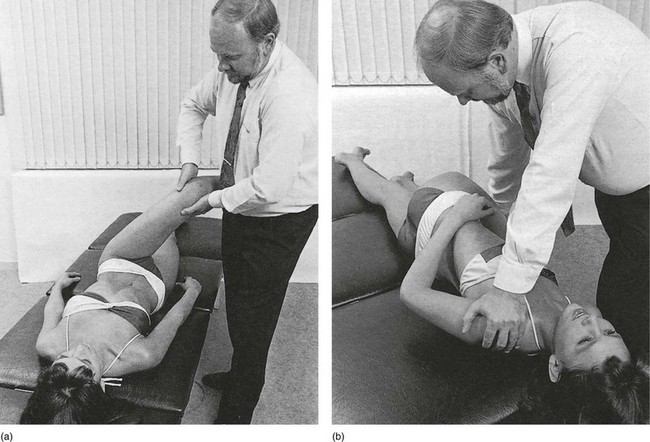

Stretch

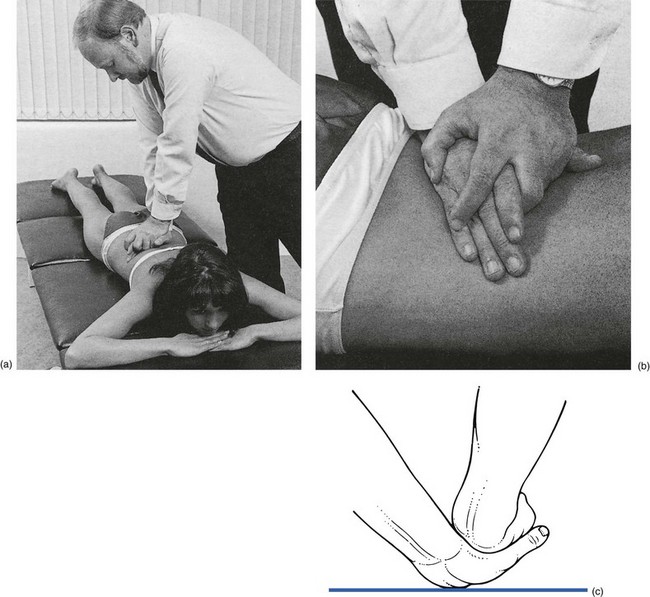

By using the body weight and leaning well over the patient, the manipulator obtains considerable distraction at the lumbar joints. At the moment the limit of tissue tension is felt, the manipulator’s body is pushed forwards on the vertically outstretched arms to apply overpressure (Fig. 40.4). At that moment a ‘click’ or ‘snap’ is nearly always heard and felt, after which the result of the manipulation is assessed.

Fig 40.4 Stretch.

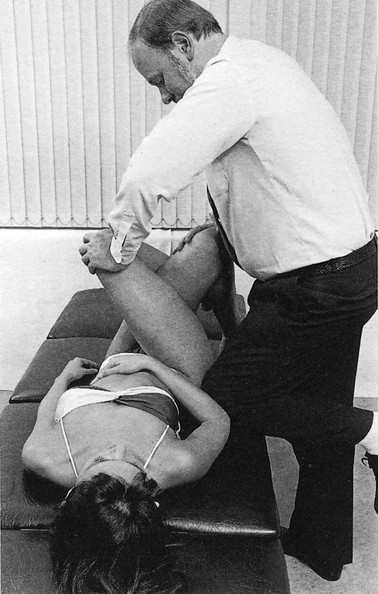

Leg crossed over

The manipulator stands on the painless side, level with the patient’s waist, facing the feet. With both hands flexing the thigh on the far side up to 90° and drawn forwards, the pelvis and lower back are rotated towards the operator. In this way, hip adduction is avoided. The ipsilateral knee of the manipulator is applied to the pelvis, if necessary, to prevent the patient from falling from the couch. Next, the contralateral forearm is turned into supination and the palm of the hand applied to the outer side of the knee. The other hand pushes the patient’s far shoulder flat on the couch (Fig. 40.5). Then rotation of the pelvis is continued until tissue tension is felt to be maximal. At that moment, rotation is forcibly increased by pressing the patient’s knee strongly and with high velocity towards the floor, using the thigh as a lever. At the same moment, the other hand maintains the position of the patient’s far shoulder (if possible) flat on the couch.

Leg crossed over with side flexion

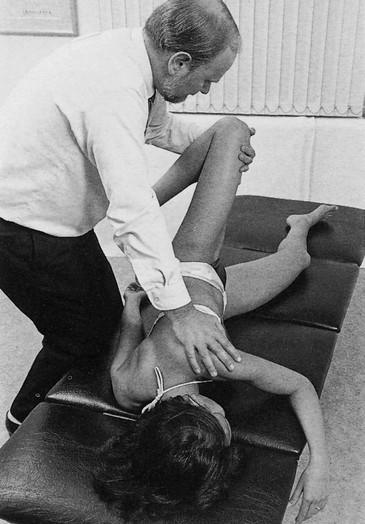

This manœuvre is a variation on the previous ‘leg crossed over’ technique and also achieves side flexion. The patient lies supine, both legs flexed and crossed, the leg on the painful side underneath. The manipulator stands on the painless side, level with the patient’s waist. Holding the patient’s knees in the hands, the manipulator moves the patient’s hips into 90° of flexion. Then both legs are twisted, in order to tilt the pelvis laterally and open up the lumbar spine on the painful side. This position is maintained at full range. The hand that has been on the patient’s uppermost knee is now freed to fix the far shoulder on the couch. The side-bent position of the lumbar spine is ensured by the manipulator’s thorax and abdomen, which are used to engage the knee from the side. Next, rotation is stepped up slowly: under the influence of gravity, the legs turn in the direction of the floor until the limit of tissue tension is felt at the end of range. At that moment, the manipulator’s thigh, engaging the uppermost knee from the side, has taken over to secure the side-bent position of the lumbar spine. Lastly, the hand at the knee is supinated to increase the manipulative force. Manipulation is performed by pressing the knee quickly downwards (Fig. 40.6). At the same moment, the other hand is used to maintain the position of the patient’s far shoulder flat on the couch, if possible. Rotation is thus forced during side flexion.

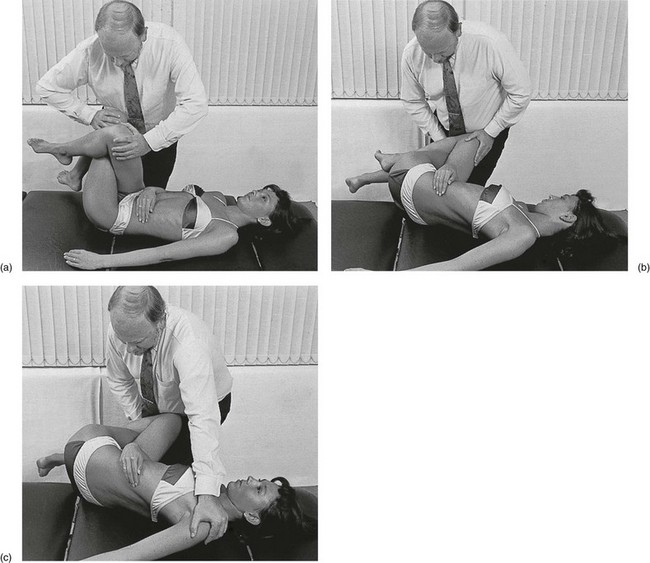

Stretch Reverse stretch

Again, the couch is adjusted to about 30 cm in height. The patient lies on the pain-free side, close to the edge of the couch where the manipulator stands. The patient’s upper hip is extended, the lower flexed to about 45° in order to stabilize this position. The upper arm hangs off the couch, the lower lies behind the back. The manipulator stands behind the patient, distal to the pelvis and facing the patient’s head. The ipsilateral hand takes hold at the anterior iliac spine and twists the pelvis backwards as far as it will go. In this position, the manipulator’s arm is fully pronated, with the hand placed against the anterior aspect of the anterior iliac spine, pushing the pelvis downwards and backwards. The other hand is placed against the scapula and pushes the thorax upwards and forwards (Fig. 40.7). Next, as the manipulator leans well over the patient, the joints are distracted by moving both hands in opposite directions, until tissue tension is felt to be maximal. Manipulation is performed by jerking the body downwards over the rigid arms. It is best to apply this overpressure at the moment of expiration.

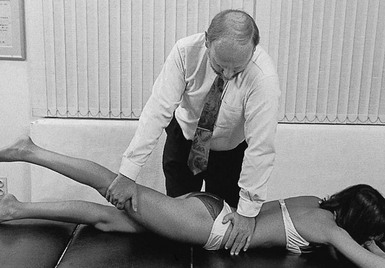

Reverse rotation with thigh

The couch is adjusted to about 60 cm in height. The patient lies on the pain-free side, the upper leg extended and the lower hip flexed to 60°, with the lower arm behind the back. The manipulator stands behind the patient, level with the lumbar spine. The ipsilateral hand grasps the upper thigh at the knee and flexes the hip to 90°, abducting the thigh horizontally. As a result, the pelvis is twisted as far as it will go. The other hand is placed against the scapula and pushes the upper thorax to the couch (Fig. 40.8). While pressure is maintained on the thorax, the patient’s upper thigh is now brought to 60° of flexion and full abduction. In some cases, it is also necessary to place a knee against the patient’s lower buttock, to prevent the pelvis from slipping backwards. The moment that the manipulator feels the limit of tissue tension, manipulation is performed by a short, sharp rotation of the manipulator’s body. This forces the arm at the thorax down, at the same time as it jerks the thigh backwards. Strong rotation and extension occur in the lumbar joints.

Fig 40.8 Reverse rotation with thigh.

Extension techniques

Central pressure

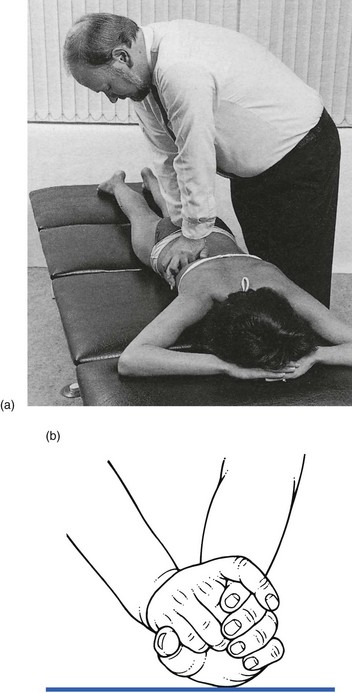

The patient lies prone on a firm couch adjusted to about 30 cm height. The manipulator stands level with the lumbar spine, facing the patient, with the knees against the edge of the couch. One hand is placed with its ulnar border at the interspace of two adjacent spinous processes (normally between S1 and L5). The other reinforces it with the heel pressing on the radial and the thumb pressing on the dorsal and ulnar sides of the lower hand (Fig. 40.9). To prevent any contact with the iliac bones, it is useful to use the right hand, standing at the patient’s left-hand side, and to turn this hand through about 45°. With the upper limbs extended and kept rigid, the manipulator leans well on to the patient’s back and extends the knees, one after the other. From this moment the body weight presses fully on the patient’s back and results in maximum tissue tension.

Unilateral pressure

The manipulator stands on the patient’s painful side, although, if the pain is central, there will be no indication whether to start on the right or on the left. The wrist of the ipsilateral hand is extended and the prominent pisiform bone is used to exert localized and unilateral pressure at the base of the spinous process of L5 or L4. It is necessary to lean well over the patient, in order to press in a slightly oblique direction (Fig. 40.10). The other hand reinforces the pressure, using the heel to press on the manipulating hand. In order for the manipulator to stay well balanced, both legs are moved slowly backwards at the moment the body moves forwards. The knees or thighs should stay in contact with the edge of the couch. Manipulation is all but identical to the previous technique, except that the thrust is now directed medially as well as downwards, which opens the joint on the painful side, at the same time also exerting some rotational stress and strong extension.

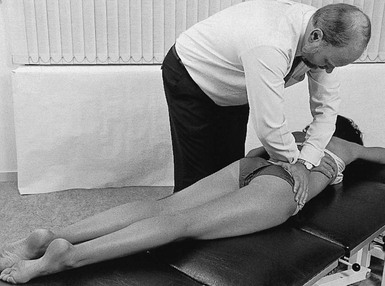

Unilateral pressure with thigh I

The patient lies prone and near to the edge of a low couch. The manipulator stands on the pain-free side, level with the pelvis. With the ipsilateral hand, the front of the knee is grasped at the painful side around its lateral aspect. The ulnar border of the other hand is placed just above the posterior spine of the ilium. Then the hip is extended and strongly adducted by leaning heavily towards the patient’s head (Fig. 40.11). This opens the joint on the side where the displacement lies. Manipulation is performed by a quick rotation of the manipulator’s trunk towards the patient’s head. In this way, the unilateral downward pressure of the lumbar hand and the upward pull of the hand on the knee are considerably intensified. This results in a combined movement of hyperextension, side flexion and rotation at the lower lumbar joints.

Fig 40.11 Unilateral pressure with thigh I.

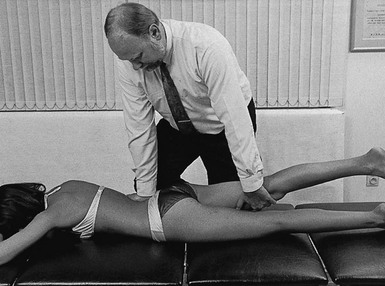

Unilateral pressure with thigh II

The patient lies in the same position as in the previous technique. The manipulator stands on the painful side. With the contralateral hand, the front of the patient’s knee is grasped around its medial aspect and the thigh is extended and adducted until the pelvis rises just off the couch. The palm of the other hand is placed on the sacrospinalis muscle covering the fourth and fifth lumbar levels on the painful side, with the forearm fully supinated (Fig. 40.12). The manipulative thrust is performed by pressing the ipsilateral knee with the hand at the same time as the patient’s thigh is forced into full extension and adduction. A forced extension at the lower lumbar joints results.

Fig 40.12 Unilateral pressure with thigh II.

Unilateral distraction

The patient lies prone and side-flexes the body to open the joint on the painful side as far as possible. The manipulator stands on the concave side, facing the patient, with the arms crossed and the elbows bent almost to a right angle. The heel of one hand is placed against the iliac crest, just lateral to the sacrospinalis muscle. The heel of the other hand is placed just under the lowest ribs (Fig. 40.13). To prevent the skin from being strained at the moment of manipulation, it is first pulled upwards with the lower hand, while the upper hand does the same downwards. Manipulation is now performed by repeated (10–20 times) forward movements of the trunk, keeping the elbows rigid. This forces the hands apart and imparts rhythmic further distraction, together with some extension at the lumbar level.

Fig 40.13 Unilateral distraction.

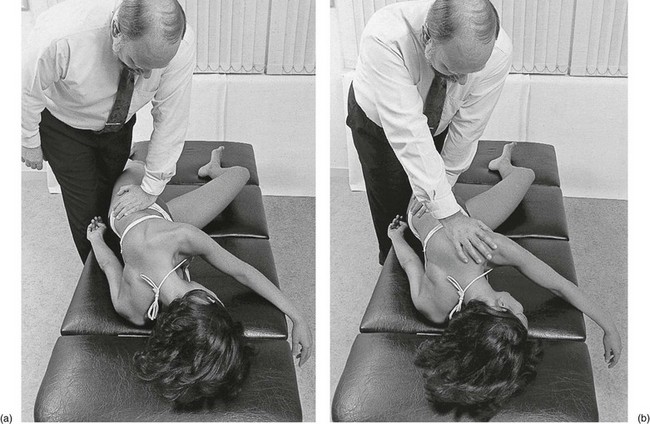

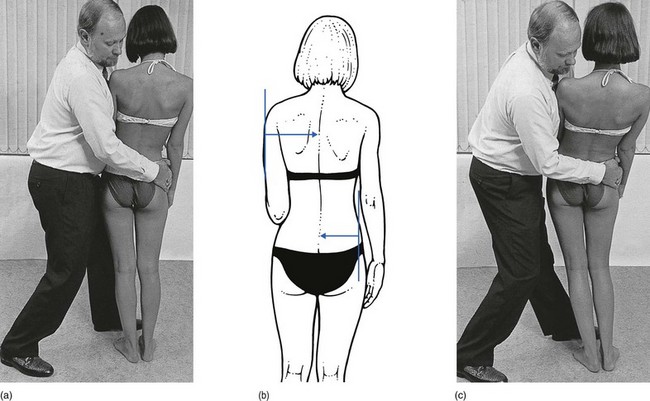

Antideviation techniques

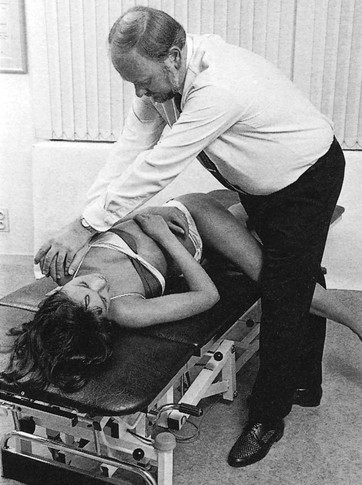

Side bending

The patient lies supine with both legs flexed and crossed, the leg on the concave side of the lumbar spine underneath. The manipulator stands on the convex side, level with the pelvis. With one hand the upper knee is pushed away, while the other is used to pull the lower knee towards the manipulator (Fig. 40.14). This simultaneous action tilts the pelvis and achieves full side flexion at the lumbar spine in the direction that was previously blocked. It is quickly repeated a number of times, whereafter the pressure is maintained for a few seconds. When there has been a previous nuclear protrusion, the extreme of range is better maintained for a minute or so. This position is consolidated either with the assistance of the manipulator’s ipsilateral knee, pushing from a distal position against the patient’s ischial tuberosity, or by using the contralateral knee to push from a lateral position against the patient’s pelvis. The manipulation is repeated until the patient can keep the trunk in a neutral position on standing.

Fig 40.14 Side bending.

Rotation–distraction

The patient lies on the side of the lumbar convexity with the upper thigh flexed to about 60°, thereby rotating the pelvis to just over 90°. The manipulator stands in front of the patient, distal to the pelvis and facing the patient’s head. The thigh of the uppermost lower limb is clasped between the manipulator’s knees, just proximal to the patient’s knee, to secure the position of the pelvis. Both hands are placed to one side of the upper thorax. Correction of the lateral tilt is achieved by pushing against the patient’s thorax in an upward and backward direction (Fig. 40.15). This correcting force should be sustained for as long as the patient can endure it. The manipulator must stand well balanced to prevent the entire body weight from pressing on the patient. After some repetitions the patient is re-examined in the standing position.

Fig 40.15 Rotation–distraction.

Side gliding

Correction and even slight overcorrection is achieved slowly, by pressing the thorax against the patient’s elbow, simultaneously pulling the pelvis from the far side towards the manipulator (Fig. 40.16). This pressure should be maintained for a couple of minutes and is repeated several times. It is essential that the movement is side-gliding rather than side-bending.

It will take at least 3–4 consecutive daily sessions to produce a lasting result. In addition, it is essential to instruct the patient in self-correction (Fig. 40.17).

Fig 40.17 Self-correction.

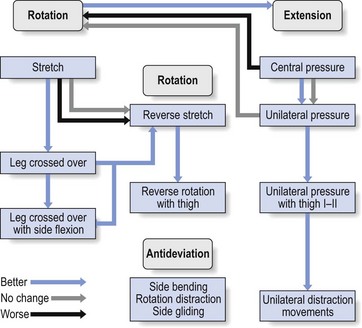

The course of a manipulative session is summarized in Figure 40.18.

Manipulation procedure

Choice of technique

• Stretch or reversed stretch in the side-lying position is usually the first technique to be tried, especially if the pain is unilateral.

• Extension techniques are chosen first in case of central pain and in elderly patients.

• Acute lumbago is unsuitable for extension techniques; rotation manœuvres usually give good results.

• Usually, L3–L4 protrusions respond better to rotation techniques.

• L5 protrusions may respond better to extension techniques, especially in elderly patients.

• In elderly patients it is also better to avoid long-lever techniques for fear of fracturing weakened bones.

• If rotation–stretch techniques lead to incomplete reduction in minor protrusions, one can move on to extension techniques.

• After the use of each technique, the result is assessed and a decision taken whether to continue with the same technique or to change. If one manœuvre has helped, it should be repeated until symptoms and signs no longer alter. Then another is tried. Experience, the result of each particular manœuvre, end-feel during exertion, the patient’s age and estimation of tolerance all affect the types of manœuvre employed.

Assessment of progress (Box 40.4)

Another important sign is ‘centralization’ of pain: a shift, after manipulation, to a more central position is regarded as an improvement.58,80,81

Assessment of outcome after each manœuvre assures the manipulator that:

Traction

Although there is still a great deal of controversy about the effectiveness of traction,82 we still consider passive sustained stretching of the low back as the treatment of choice for nuclear, reducible disc protrusions causing backache and/or sciatica, unless there are specific contraindications.

Despite the poor design of most of the studies,83 traction has been shown to be more effective than corsets, bed rest, hot packs and massages.79,84–86

Historical note

The Ancient Egyptians utilized the beneficial effect of axial traction.87 An illustration of traction employed by the Spanish–Arabian physician Abu’L Qasim (1013–1106) of Cordoba is reproduced by Schiötz and Cyriax in their book on manipulation past and present.20 In the same book, illustrations show the way in which traction was used by Hippocrates (400 bc) and Galen (ad 131–202). A 14th-century method of manipulation during traction is illustrated in Figure 40.19.

Nowadays, two methods of performing traction are practised. The sustained manner, as described in this book and first suggested by Cyriax in 1950,88 and several types of intermittent traction. Intermittent traction can be done either electrically, manually (by a therapist) or by the patient (autotraction). However, nearly all reported work has shown all types of intermittent traction to be ineffective.89,90

Effects of sustained traction

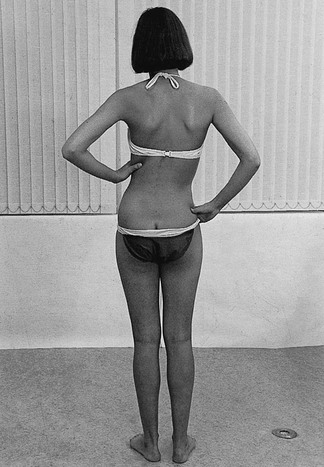

Several studies have investigated axial traction. It has been established that during sustained traction at least three effects result (Fig. 40.20).

Fig 40.20 Effects of sustained traction. (a) Before traction, nuclear protrusion posteriorly displaced. (b) During traction: the intervertebral space enlarges; the posterior longitudinal ligament is tautened; a negative intradiscal pressure is created. (c) After traction, reduction is maintained (after Mathews91).

The space between the vertebral bodies enlarges

This is an important precondition for a displacement to recede.

In young men, sustained traction of 60 kg, applied for 1 hour, results in an increased body length of 10–30 mm, which is thereafter lost at the rate of 4 mm/h.92 In an excised lumbar spine, sustained traction of 10–30 kg increases each joint space by 1.5 mm.93 Vertebral separation is greatest in those subjects with wide disc spaces and least where there is evidence of disc degeneration.94

The effect of lumbar sustained traction on stature has also been studied in 10 healthy young subjects; the investigators confirmed the significant increase in stature but also that this increase was over and above that known to occur when the load is taken off the spine by lying down.95 The findings suggest that most of the vertebral separation takes place in the first 30 minutes. It has also been established that the enlargement between two consecutive lumbar endplates during normal traction is between 1.0 and 1.5 mm, which is 10–15% of the thickness of the disc.96–98 Other studies demonstrate a widening of the lumbar intervertebral space of between 3 and 8 mm measured on radiographs of patients undergoing gravitational traction.99,100

The heavy lumbar paravertebral musculature normally exerts significant resistance to distraction. At least 30–35 kg of traction, not dissipated by friction, is required to influence the lumbar spine.101 Other work has demonstrated that a traction force of at least 25% of the body weight is necessary to achieve distraction of the lumbar vertebrae against the inertia of muscular resistance of the body.102 This supports an earlier study103 in which any traction power less than 25% of body weight was regarded as a placebo.

The posterior longitudinal ligament is tautened, exerting a centripetal force at the back of the joint

The increasing tension in this ligament is certainly of great therapeutic value, particularly if the protrusion is located anterior to, and remains in close contact with the ligament. Traction will therefore be less effective if the protrusion is laterally placed – a conclusion confirmed by computed tomography (CT) investigation of the effect of static horizontal traction on lumbar disc herniations: ‘The clinical responses of the herniation to conservative treatment and the location of herniated nuclear material seem to be related. Traction is more effective on median and posterolateral herniation cases, and clinical improvement is evident in these cases, but traction is not very effective on lateral herniations.’104 Also, re-entry of ruptured or sequestered disc material into the intervertebral disc is not possible (Fig. 40.21).

Suction draws the protrusion towards the centre of the joint

It is believed, on the basis of biomechanical calculations, that significant intradiscal negative pressure may be produced during sustained traction.105 A traction load of 30 kg caused a lowering of the intradiscal pressure from 30 to 10 kp in the L3 intervertebral disc.106 In another study, intradiscal pressure demonstrated an inverse relationship to the tension applied. Tension in the upper range was observed to decompress the nucleus pulposus significantly, to below 100 mm Hg.107 Discography has established that the decrease in intradiscal pressure causes a suction effect with centripetal forces on the contents.93 An interesting Chinese study investigated the changes in intradiscal pressure and intervertebral disc height on 31 prolapsed discs under traction. It was demonstrated that the intradiscal pressure decreased as the intervertebral distance increased in most cases under traction.108,98

Repair of the disc lesion

It has also been suggested109,110 that, during episodes of disc decompression, nutrition is improved, reparative collagen is deposited and natural healing of annulus tears and fissures is promoted.

There is increased motor activity of the sacrospinalis muscles on an electromyogram during traction, until the mechanoreceptors in the tendons are stimulated.111 From that moment, motor activity is inhibited, the intervertebral joint takes the strain and reduction of the pulpy mass starts slowly. Electromyographic silence is reached after 3 minutes. This suggests that traction must be sustained. A study that measured the intradiscal pressure during 30 seconds of passive traction performed by two therapists and during 2 minutes’ autotraction with 50 kg weight112 has established that intradiscal pressure did not alter much in passive traction, whereas autotraction increased the pressure considerably. These findings strongly contrast with those of sustained traction, which makes it obvious that only the latter is able to diminish a nuclear protrusion in volume and return it to its normal position.

Indications for traction

Nuclear disc protrusions

Pulpy nuclear protrusions which remain contained and in contact with the posterior longitudinal ligament (see Fig. 40.21) are more effectively treated by traction just as hard annular protrusions are more readily treated by manipulation. Cyriax always said: ‘You can hit a nail with a hammer, but treacle must be sucked.’

The distinction between these different types of disc protrusion is not always as clear as in these examples. Nevertheless, for therapeutic reasons, it is important to differentiate between these mechanisms. The summary given in Table 40.1 may be helpful.

Table 40.1

Differences between nuclear and annular protrusions

| Nuclear protrusion | Annular protrusion | |

| History | ||

| Age (years) | < 60 | All ages |

| Onset | After a lot of stooping and lifting Pain increasingly evoked by sitting in a kyphotic posture |

During bending forwards and coming up again, abrupt displacement with a click, initiating acute lumbago |

| Backache after exertion | Backache as soon as exertion starts | |

| Clinical examination | Partial articular pattern | Partial articular pattern |

| Pain on pinching the lesion in backache (not in lumbago or over the age of 60) | Pain on side bending away from the painful side |

Primary posterolateral protrusions

Considering the therapeutic approach in a primary posterolateral protrusion, Cyriax21 (his p. 317) gives the following advice: ‘[S]uch a protrusion of a month or two’s standing should be reduced by daily traction.’ However, if relapse occurs after a successful reduction, or the protrusion has persisted for 3 or 4 months, it is better to leave it where it is, especially in a young patient with slight pain only, which is the common situation. Cyriax again: ‘Spontaneous recovery usually takes nine months from the onset of root pain, and the strong tendency to recurrence is largely obviated by allowing the patient to get well of himself. [However] he should be kept under observation until the protrusion is stable at its maximum size, i.e. the range of straight-leg raising has stopped decreasing and is found unaltered at two examinations a fortnight apart. This is the moment for one or two inductions of epidural local anaesthesia which usually abolish the root pain in a few weeks.’

Contraindications

Respiratory or cardiac insufficiency

The patient may not be able to lie down at all, let alone tolerate the harness.113

Painful reactions

If traction increases pain in the back or in the leg, the patient is unsuited to it. This often happens in chronic low back pain and sciatica, where the lumbar spine is fixed in flexion. Pain that increases as soon as the traction starts may indicate a worsening of the condition and is therefore reason enough to stop the treatment.114

Cases in which traction is not useful

Traction procedure

Traction apparatus

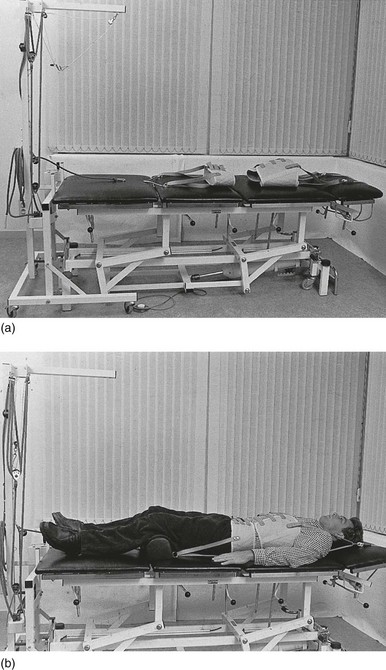

There is mechanical equipment that has the advantages of the electrical appliance: constant traction force during the entire session (Fig. 40.22).

Patient’s posture

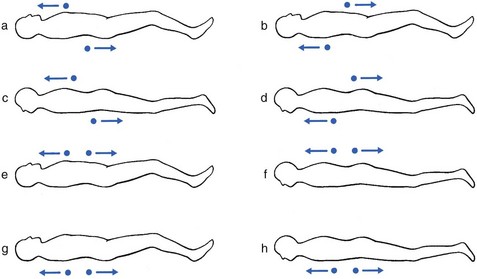

• If both flexion and extension are painful (or neither), the patient may lie supine or prone. One strap is situated posteriorly, and the other anteriorly. In this way, the articular surfaces stay parallel during distraction (Fig. 40.23a–d).

• If flexion hurts and extension is pain-free, traction is carried out with the lumbar spine in slight lordosis. The patient is positioned supine with a small pillow supporting the lumbar spine, or lies prone. In both positions, the straps of the harnesses are situated anteriorly (Fig. 40.23e,f).

• If extension hurts and flexion is pain-free, traction is carried out with the lumbar spine in slight kyphosis. The patient is positioned supine with the lower legs supported on a small bench and the knees bent upwards, or lies prone. In both positions, the straps of the harnesses are situated posteriorly (Fig. 40.23g,h).

Thus, eight different positions may be used. In practice, however, the positions regularly used are:

Interval between treatments

Traction must be given daily, as the intention is to achieve greater reduction in half an hour than the patient can reverse by weight bearing on the joint for the rest of the day. It is remarkable that this should be possible. Furthermore, traction is normally still effective with an interval over the weekend, provided that the patient relaxes on these days – lying down at regular intervals and not sitting for a longer time than is absolutely necessary. If these rules are neglected, the protrusion is likely to have returned to the same size by the time of the next visit. In an urgent case, traction can be performed more than once a day. Alternatively, one long stretch of up to an hour has proved effective in these circumstances. Passive back extension and prone lying can also be useful supplements.58 If traction has not begun to have an effect after a few days, the question is whether to use a different position on the couch or a different position for the straps. If these alterations are made and the patient has not begun to improve after 2 weeks, traction should be abandoned. The physiotherapist should not despair too soon, however, as many patients only begin to improve during the second week. Obviously, if a patient is much better but not completely well after a fortnight, a third week’s daily treatment is justified. In young adults with backache and long-standing bilateral limitation of straight leg raising, it may even take a month before any improvement is noted.

Procedure (Box 40.6)

The patient is then shown how to put shoes on and how to sit in a car (see p. 583). If the lower back still feels stiff on leaving the room, it is better for the patient to take a short walk before getting into a vehicle. A lumbar support – for example, a rolled towel – is often useful to prevent the patient from sagging. In this way, the intradiscal pressure is kept as low as possible. However, during the whole period of treatment, the patient should be instructed to avoid sitting and stooping as much as possible.

Results

One study measured the effects of lumbar traction with three different amounts of force (10%, 30% and 60% of body weight) on pain-free straight leg raise test of 10 patients suffering from sciatica caused by discoradicular interactions. The straight leg raise measurements were found to be significantly greater immediately following 30% and 60% of body-weight traction, as compared to 10% of body-weight traction.115

The effect of sustained traction on herniated nuclear material has also been investigated with CT. One study investigated the regression of displaced nuclear tissue during and after traction.104 Patients were between 20 and 40 years of age. The duration of traction application was 40 minutes, with an applied load of 45 kg. Evaluation of the results showed a regression of herniated nuclear material in 78.5% of median herniations, 66.6% of posterolateral herniations and 57.1% of lateral herniations. Low back and leg pain decreased in all cases, except when the disc was fragmented or calcified. A recent, prospective, randomized, controlled study investigated the effects of continuous lumbar traction in patients with lumbar disc herniation on clinical findings and size of the herniated disc measured by CT.116 They found a significant improvement in symptoms and signs, together with a decrease in size of the herniated disc material as measured by CT.

Alternative procedures for reducing nuclear protrusions

McKenzie’s reduction techniques

The thinking behind McKenzie’s approach is based on Cyriax’s disc theory. Being a physiotherapist, he has developed a prophylactic and therapeutic concept based primarily on self-applied repetitive exercises and/or positioning by the patient in order to reduce the nuclear displacement that leads to the ‘derangement syndrome’. A classification – derangements 1–7 – is made according to the localization of the pain and the presence or absence of deviation, either in kyphosis or in scoliosis.117,118

The patient is taught how to apply progressively increasing mechanical forces that aim to cause centralization and subsequent diminution of pain. The therapist’s intervention is only necessary when the results of self-treatment are insufficient. The choice of technique is based on the results obtained during repetitive movements – flexion, extension and side gliding – in the examination.119 Those movements that reduce, centralize or abolish symptoms during testing are used as treatment procedures.120 The reader is referred to McKenzie’s books and articles for further details.121–123