Disorders of the ankle and subtalar joints

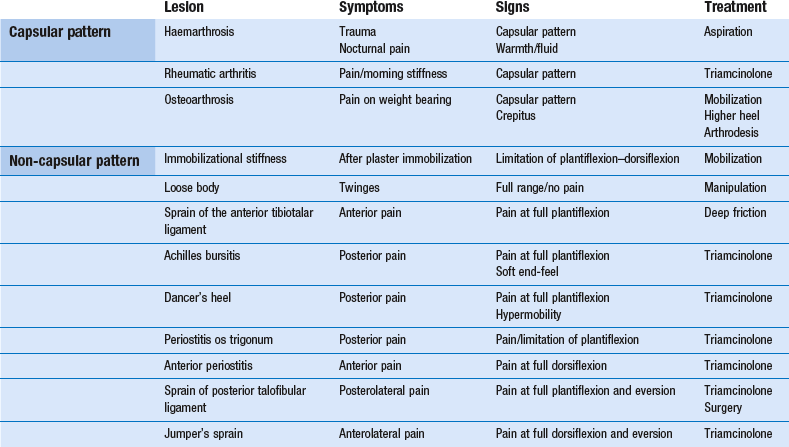

The ankle joint

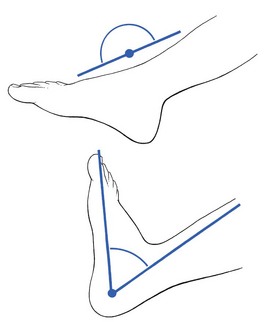

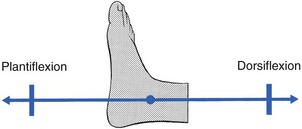

The ankle is a very simple joint, allowing only plantiflexion–dorsiflexion movement. Normally the foot comes into a straight line with the lower leg during plantiflexion and can be moved to less than a right angle during dorsiflexion (Fig. 58.1).

Capsular pattern

The capsular pattern of the ankle joint is slightly more limitation of plantiflexion than of dorsiflexion (Fig. 58.2). In patients with short calf muscles, however, dorsiflexion ceases before the extreme of the possible articular range is reached, which raises the question of whether limitation is capsular or non-capsular. In such a case, a clinical diagnosis of arthritis at the ankle rests entirely on the end-feel. Limitation of plantiflexion with a hard end-feel indicates arthritis. If full dorsiflexion cannot be reached because of short calf muscles, a softer end-feel is detected.

Rheumatoid conditions

Rheumatoid conditions, so often affecting the other tarsal joints, are not found in the ankle joint. If it does become inflamed, this occurs only after a long evolution of rheumatoid disease. Exceptions are psoriatic arthritis and gout, which are not uncommon at this joint. In acute arthritis without an apparent precipitating cause, a gout attack must always be suspected, especially if the patient is a middle-aged man. Gout attacks the ankle joint in almost 50% of all gout patients.1 It responds very well to one or two injections with 20 mg of triamcinolone.

Haemarthrosis

Haemarthrosis of the ankle is not uncommon in ankle sprains. It occurs after direct trauma – for example, in soccer players. A capsular pattern at the ankle joint after an inversion sprain or direct trauma always suggests haemarthrosis. Because blood is a strong irritant to cartilage and provokes early arthrosis, it should be evacuated at once. A radiograph of the talus and/or a magnetic resonance image (MRI) must be taken to exclude osteochondral fracture.2

Avascular necrosis

Avascular necrosis is bone death due to ischaemia. Loss of blood supply to the bone can be caused by an injury (trauma-related avascular necrosis), such as ankle sprain, joint dislocation or fracture of the dome of the talus, or can stem from certain risk factors (non-traumatic avascular necrosis), such as some medications (steroids), blood coagulation disorders or alcohol abuse. The earliest clinical manifestation is the finding of a capsular pattern with a spastic end-feel. MRI is the most sensitive technique for detecting talar avascular necrosis and can be used when the condition is strongly suspected clinically despite normal radiographic findings.3

Osteoarthrosis

Osteoarthrosis is often the result of shearing strains – for instance, after malunion of a tibiofibular fracture. Early arthrosis has also been reported after aseptic necrosis of the talus.4 In sports in which repeated and severe sprains of the ankle occur, such as rugby, American football and judo, osteoarthrosis is common and often occurs early. Clinical examination shows a capsular pattern with a hard end-feel. Radiography may show cartilage loss, a flattened talar dome, subchondral sclerosis, intraosseous cysts and peripheral osteophytes.

The best conservative treatment is to fit the patient’s shoe with a higher heel, which enables walking without much dorsiflexion at the ankle joint. However, conservative treatment of painful osteoarthrosis is seldom satisfactory. Sometimes one or two injections of 20 mg of triamcinolone may help but should not be repeated too often for fear of further destruction of the joint from steroid arthropathy. During the last decade, the use of visco-supplementation (intra-articular injections of high-molecular-weight solutions of hyaluronan to restore the rheologic properties of the synovial fluid) has been shown to be safe and efficacious in the treatment of osteoarthrosis of the ankle.5 If the symptoms warrant and the condition worsens, arthrodesis is the only satisfactory treatment and is usually acceptable, provided the patient is fitted with adequate shoes that permit walking without difficulty.

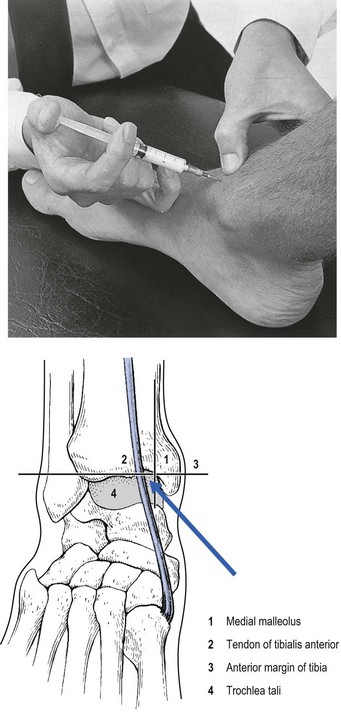

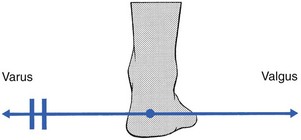

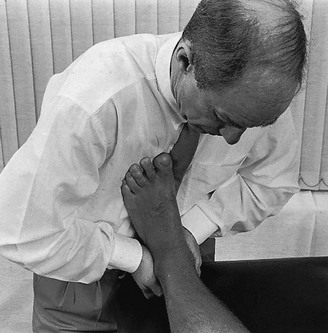

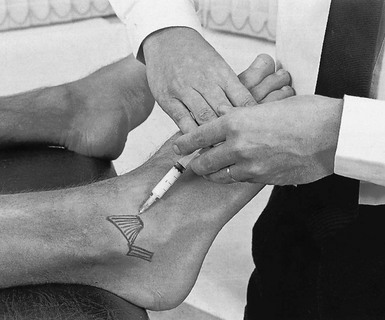

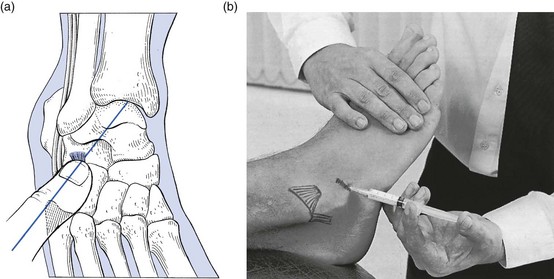

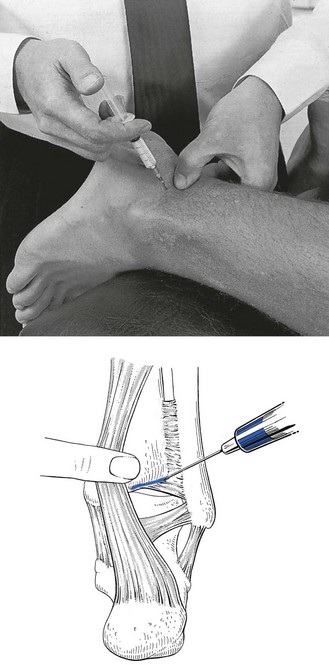

Injection or aspiration technique of the ankle joint

This is a simple procedure. The patient lies in the supine position, the knee bent and the foot flat on the couch, which forces the ankle into a degree of plantar flexion. The medial malleolus and the tendon of the tibialis anterior are easily identified. The trochlea tali is found by flexing and extending the talus under the tibia. A 4 cm needle is introduced between the medial malleolus and the tibialis anterior tendon, just under the edge of the tibia (Fig. 58.3). The tip lies intra-articularly when it strikes cartilage.

Non-capsular pattern

Immobilizational stiffness

Limitation of both plantiflexion and dorsiflexion often occurs after long-standing immobilization of the ankle. Only strong and daily mobilization of the joint will afford any benefit. Traction and translation techniques can be of great value in the treatment of this post-immobilization stiffness.6 Some authors report increased motion and pain relief after arthroscopy.7

Loose body in the ankle joint

A loose body with an osseous nucleus is well known as a result of transchondral fracture (osteochondritis dissecans) of the dome of the talus. In most cases, the aetiology is inversion sprain.8,9 The diagnosis is made by radiography or computed tomography (CT), and symptoms may warrant surgery. However, when there is only a loose cartilaginous fragment without an osseous nucleus, radiographs are negative, and the diagnosis must be made almost entirely on the history.

Differential diagnosis

The differential diagnosis is between a loose body in the subtalar joint (p. 1214), distal tibiofibular ligament deficiency (p. 1230), a snapping peroneal tendon (p. 759) or an unstable ankle (p. 1229).

Other lesions with a non-capsular pattern

Sprain of the anterior tibiotalar ligament

In soccer players, new bone may form on the upper surface of the talar neck, as a result of traction at the insertion of the ligament. This has been called ‘soccer ankle’.10 The diagnosis is made from the radiograph. If pain persists, the bone spurs may be removed surgically.

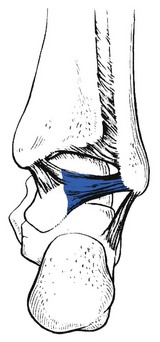

Achilles bursitis

If the bursa, normally found between the Achilles tendon, the upper surface of the calcaneus and the tibia (Fig. 58.5), becomes inflamed, pain will be elicited when it is squeezed between the posterior side of the tibia and the upper surface of the calcaneus at the extreme of passive plantiflexion.11,12 Full plantiflexion evokes pain, this time at the back of the heel. Rising on tiptoe remains negative, thus excluding the Achilles tendon as a cause. Palpation reveals a tender spot anterior to the tendon, close to the superior border of the calcaneus.13

Fig 58.5 The Achilles bursa.

Dancer’s heel (posterior periostitis)

This is a bruising of the periosteum at the back of the lower tibia. The lesion lies at the junction of the cartilage and periosteum, and is caused by pressure from the upper edge of the posterior surface of the talus. It occurs in ballet dancers who, during training, develop a hypermobility in plantiflexion at the ankle joint, usually as a result of pointe work. The repetitive engagement of talus against the posterior tibial edge induces periosteal bruising.14–16 Sometimes the condition results from a single vigorous plantiflexion strain, such as when a soccer player kicks the ball from underneath.

The patient complains of pain at the back of the heel during plantiflexion. Clinical examination reveals an excessive range of movement and pain is reproduced by forced plantiflexion of the ankle. Dancer’s heel must be differentiated from Achilles bursitis.17 In the latter the end-feel is soft, giving the impression of pinching some tissue, whereas in a dancer’s heel the end-feel is normal.

The patient adopts a prone-lying position, the foot over the edge of the couch. The posterior articular margin of the tibia lies approximately 2 cm above the line joining the tips of the malleoli. A 2 mL syringe is filled with a steroid suspension and fitted with a fine needle, 4 cm long. The Achilles tendon is pushed medially (Fig. 58.6). The needle is inserted vertically downwards, lateral to the Achilles tendon, 2 cm above the line connecting the malleoli. The most difficult part of the whole procedure is now to palpate with the tip of the needle and feel for the line at which bone (tibial periosteum) gives way to articular cartilage. The infiltration is now made by placing a line of little droplets all along and just above this cartilaginoperiosteal border.

Fig 58.6 Infiltration of dancer’s heel.

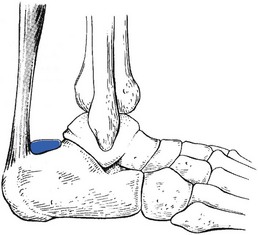

Pinching of the os trigonum

Posterior ankle pain during extreme plantiflexion can also be caused by periostitis of the os trigonum. This accessory bone, located just behind the talus, is found in about 10% of the population.18 Sometimes the ossicle is fused to the talus and is then called Stieda’s process. With extreme plantiflexion, such as in ballet or soccer, the os trigonum may be pinched between talus and tibia and produce periostitis and pain.19 The clinical diagnosis is made when posterior pain during passive plantiflexion is seen in combination with slight limitation of plantiflexion movement and a hard end-feel. Diagnosis can be confirmed by an MRI examination.20 Sometimes a painful outcrop can be palpated in the posterior triangle.21 Martin22 noted not only that this reduced dorsiflexion mobility but that painfully resisted plantiflexion of the big toe was also present. This is caused by fibrosis of the flexor hallucis longus tendon in the fibro-osseous canal behind the talus.

Treatment is infiltration with triamcinolone. If pain persists, surgical removal can be considered.

Anterior periostitis

The converse of a dancer’s heel is periostitis at the anterior margin of the tibia. This is caused by pressure of the anterior lip of the tibia on the talar neck during an extreme dorsiflexion movement at the ankle.23 The typical situation inducing this injury is when a gymnast lands flat on the feet but with the knees bent so that the ankle is forced into extreme dorsiflexion. The result is immediate pain at the front of the ankle. The sharp component of the pain disappears but the lesion does not heal completely, leaving the patient with pain during extreme dorsiflexion movements. In ballet dancers, repeated and extreme dorsiflexion necessitated by the demi-plié position can lead to periostitis of the anterior tibial lip.24,25

Treatment is one infiltration with triamcinolone, along the anterior tibial margin. This is within the reach of a palpating finger and therefore the infiltration is easy to perform. The results are good. In recurrent cases, the patient is referred for arthroscopic removal of the bony impingement.26

Sprain of the posterior talofibular ligament

Sprain of the posterior talofibular ligament (Fig. 58.7) is rare. The diagnosis is difficult to make if the examiner is not aware of the possibility of this lesion being present. The only painful movement during the routine functional examination is passive eversion of the foot during full plantiflexion – a movement performed to test the anterior fasciculus of the deltoid ligament. If the pain is posterolateral instead of anteromedial, it is obvious that a tissue is being pinched rather than stretched and the condition can be considered.

Fig 58.7 The posterior talofibular ligament.

Jumper’s sprain (lateral periostitis)

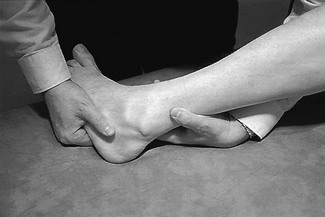

This is one of the classic lesions sustained by high jumpers. Before the athlete takes off to jump, the foot is forcefully twisted in valgus and dorsiflexion. Apart from lesions at the inner side of the ankle (strain of the deltoid ligament and elongation of the tibialis posterior tendon), compression at the outer side can result. During this extreme movement, the superolateral aspect of the anterior margin of the calcaneus can impinge against the inferior and anterior edge of the fibula and produce bruising, which results in traumatic periostitis.27 Sometimes the impingement leads to chronic inflammation of the talofibular ligament, resulting in hypertrophic scar tissue.28

Examination reveals nothing if only the standard functional tests are performed. When the possibility of this lesion is suspected, combined dorsiflexion–valgus movement is performed to reproduce the pain (Fig. 58.8). If this manual stress is not sufficient to elicit the usual pain, the patient is asked to stand, squat with the foot flat on the ground and twist the heel into valgus. Palpation reveals localized tenderness at the anterioinferior surface of the fibula.

Fig 58.8 Accessory test in jumper’s sprain.

One or two injections of triamcinolone bring total relief, provided the athlete avoids sustaining the same trauma. Normally, a slight inner wedge (0.5 cm) within the shoe is needed, which prevents further bruising of the fibula during ‘take-off’. Those patients refractory to conservative treatment require arthroscopic debridement.29,30

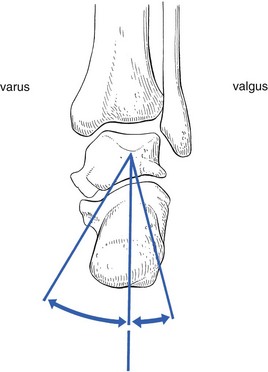

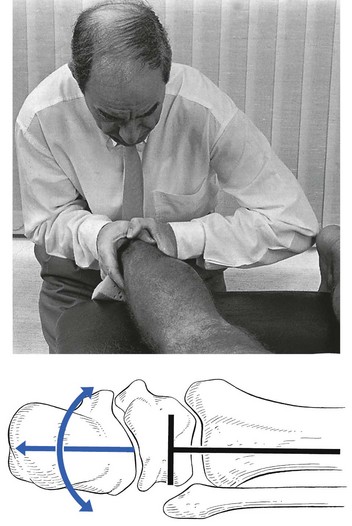

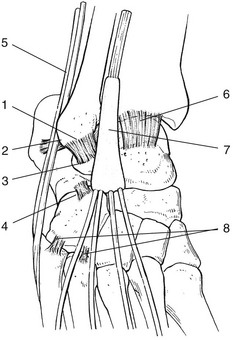

The subtalar (talocalcaneal) joint

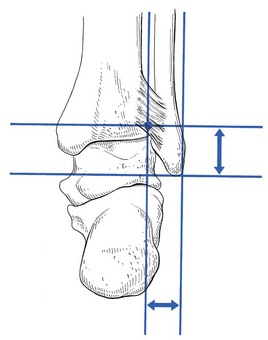

The subtalar joint allows movement in two directions only: varus and valgus. Motion takes place around an axis through the talus (Fig. 58.9), the axis being at a 15° medial angle to a line drawn through the calcaneus and the second metatarsal.

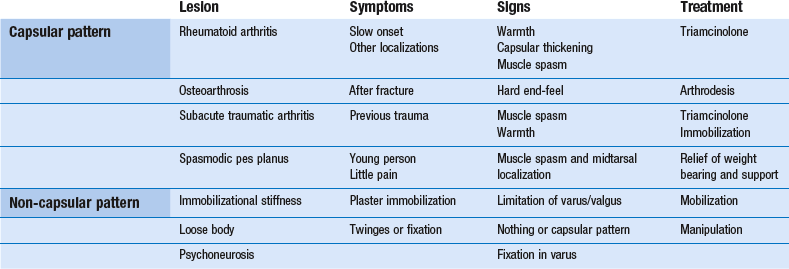

Capsular pattern

The capsular pattern (Fig. 58.10) is progressive limitation of varus with, eventually, fixation in valgus. The valgus position is maintained by spasm of the peronei muscles.

Rheumatoid disorders

In addition to the limitation of movement towards varus by muscle spasm, local heat is present and synovial thickening can be palpated. Very often, the midtarsal joint is affected as well. In rheumatoid arthritis, the arthritis is often accompanied by characteristic changes in other joints. The possibility of early ankylosing spondylitis should be kept in mind when a young patient presents with arthritis of the subtalar joint. An early manifestation of arthritis in the subtalar and midtarsal joints is also a common finding in juvenile idiopathic arthritis.31,32 In the case of an acute joint inflammation, gout should not be forgotten.

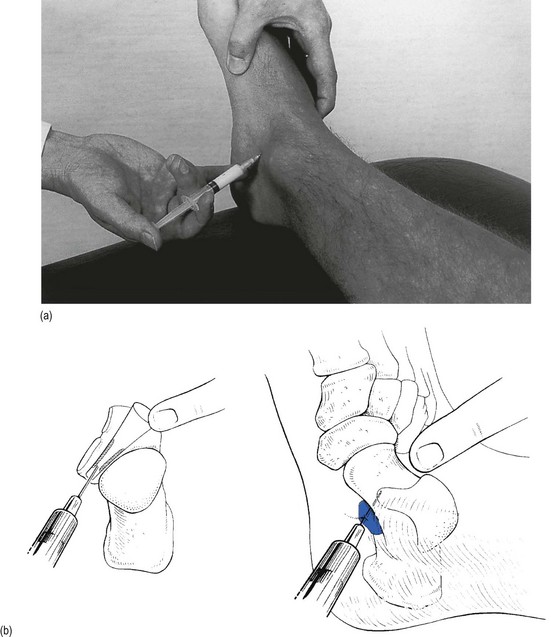

Treatment

A 2 mL syringe is filled with steroid suspension and fitted with a thin 2 cm needle. As there may be muscle spasm, the joint is fixed in valgus to create room to insert the needle from the medial side, which must be done just above the sustentaculum tali and parallel to the joint surface. The index finger of the palpating hand is placed at the lateral end of the sinus tarsi (Fig. 58.11). The needle is moved in the direction of and slightly anterior to the palpating finger. Usually it meets bone after 1 cm. The needle must then be manœuvred until it is felt to slip in further without resistance. The tip then lies within the anterior chamber of the joint, and 1 mL of the suspension is injected. The needle is then partly withdrawn and reinserted in a 45° posterior direction, where it enters the posterior chamber, and the remaining 1 mL is injected.

Non-capsular pattern

Immobilizational stiffness

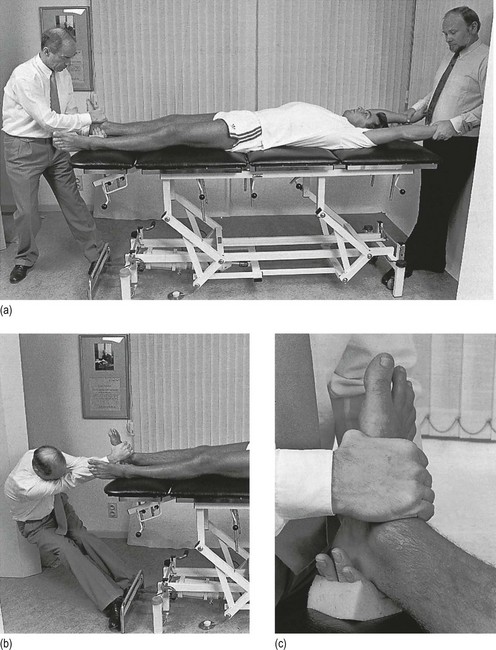

The patient lies face upwards on the couch. The therapist stands at the patient’s foot. The fingers are clasped behind the heel and the calcaneus is grasped as strongly as possible between the palms of the hands. The elbows are brought forwards in order to dorsiflex the foot. This position (Fig. 58.12) immobilizes the talus in the mortice. Mobilization is performed by swinging the body from one side to the other. This forcing must be repeated for 10–20 minutes at each session, with the greatest possible vigour.

Loose body

The patient lies prone, pulling himself or herself upwards at the upper edge of the couch until the dorsum of the foot engages the lower edge. This forces the foot into slight plantiflexion. The manipulator stands behind the patient and locks both hands around the heel, so that the crossed fingers are placed between the dorsum of the foot and the edge of the couch. The fingers are protected by a thick layer of foam. The thumbs are crossed at the dorsum of the calcaneus. In order to exert the utmost possible traction, the feet are placed against the legs of the couch and the body leans backwards. The elbows stay in line with the calcaneus, the abdomen close to the patient’s foot (Fig. 58.13). The traction produced by the body weight is reinforced by a pronation movement of both forearms. Varus–valgus movements are forced at the joint by repeatedly swinging the shoulders from one side to the other. During the whole procedure, the patient is told to maintain the pulling position and not to allow any downward movement of the body.

Disorders of the subtalar joint are summarized in Table 58.2.

Painful conditions at the heel

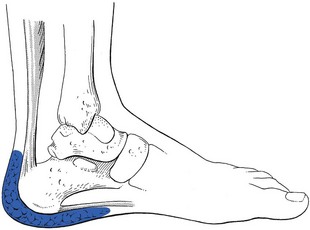

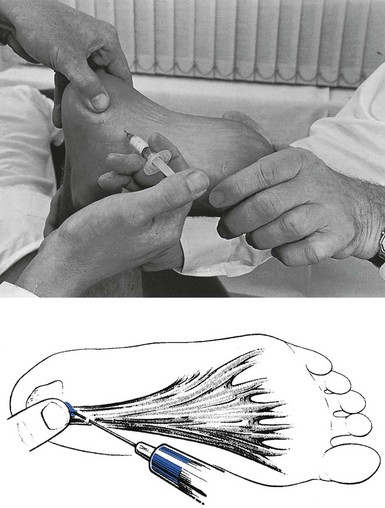

Plantar fasciitis

Plantar fasciitis is most commonly a disorder of middle age, and men and women are affected equally. Risk factors include obesity and spending prolonged periods standing or walking, particularly on hard floors.33 It is also more common among middle-aged athletes, in whom it accounts for about 10% of running injuries.34 The lesion is usually an overuse phenomenon, occurring in the presence of predisposing anatomical, biomechanical or environmental factors that put too much strain on the plantar fascia.35,36 The condition seems to be more common in people with a valgus deformity, because this flattens the foot and puts more strain on the fascia.37 Short calf muscles can also be the cause of an overstrained fascia. In this condition, the Achilles tendon tends to pull the heel upwards during standing, which stresses the longitudinal arch and the fascia.38

Functional examination of the foot and the ankle is negative. The only positive sign is the detection of a point of deep tenderness, usually situated at the anteromedial portion of the calcaneus – the origin of the plantar fascia. Exceptionally, the tenderness is not at the tenoperiosteal junction but in the body of the fascia, between its origin on the calcaneus and the forefoot. Ultrasound examination can objectively confirm the clinical diagnosis39–41 but is usually not needed.

Traction spurs, projecting forwards at the anterior border of the calcaneus, are commonly seen on radiographs and traditionally have been implicated as the cause of the painful heel.42 However, there is no relation between the spur and pain. The cause of the pain is the plantar fascial tendinitis resulting from excessive tension. The presence of a spur does not determine whether or not the patient has symptoms because a spur is very often not found in patients with obvious signs and symptoms of plantar fasciitis. Therefore a radiograph is of no particular assistance in the diagnosis of plantar fasciitis.

Treatment

The classic conservative treatment methods range from application of a heel cup, heel cushion, night splints, walking cast and steroid injection to rest, ice and anti-inflammatory drugs.43–45 Recently, extracorporeal shock wave therapy (ESWT) has been advocated for treatment of this condition. While the first placebo-controlled trials of ESWT in chronic plantar fasciitis reported benefit of variable magnitude,46,47 later studies concluded that shock-wave treatment was no more effective than conventional physiotherapy when evaluated 3 months after the end of treatment.48,49 Another study showed that treatment with corticosteroid injections was more efficacious and several times more cost-effective than ESWT in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.50

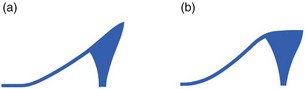

We have found the combination of alleviating the strain on the plantar fascia and one or two localized infiltrations with triamcinolone to be effective in almost every case of plantar fasciitis. The most important measure to alleviate tension on the plantar fascia is to raise the heel horizontally by 5–10 mm, which will drop the forefoot during weight bearing. This has a double effect: first, it shortens the distance between metatarsus and calcaneus and therefore directly relieves the fascia of strain; second, it removes the tension on the Achilles tendon and therefore indirectly relaxes the tension on the fascia. A high heel can afford immediate relief, provided the upper surface is horizontal and not wedge-shaped, as is the case in women’s shoes (Fig. 58.14); in the latter, a wedge that is thicker anteriorly is placed in the shoe to render the upper surface of the heel horizontal.

Results of the infiltration depend entirely on its accuracy. It is extremely important to localize exactly the site and the extent of the lesion before the needle is introduced. Palpation and infiltration should therefore be done with great care. Some authors even suggest placing the needle under ultrasound guidance,51,52 although this is seldom really necessary.

In the exceptional case when conservative treatment fails, the patient is sent for operative plantar fascia release. The results in terms of symptomatic relief are generally good.53

If an abnormal valgus position of the heel is present, a small inner wedge should be built in as well.54,55

The patient’s foot is held in dorsiflexion, either with the dorsum of the injecting hand or by an assistant. This position renders the plantar fascia taut and creates more room for the needle, which aims towards the palpating thumb on the tender spot. After traversing the resistant fascia, it touches bone (Fig. 58.15). The affected area at the tenoperiosteal border is now infiltrated.

Fig 58.15 Injection in plantar fasciitis.

Alternatively, tenotomy of the fascial origin at the heel under local anaesthesia may be required.56 This minor operation is followed by a couple of days’ bed rest and exercises for the short plantiflexor muscles of the foot.

Plantar fascial tear

Like a ruptured Achilles tendon, a plantar fascial tear occurs mostly in middle-aged athletes.57 The presentation is sudden pain in the midfoot during a sprint or a jump. There is an area of ecchymosis on the sole.58 Palpation reveals a tender and swollen area at the medial plantar aspect of the foot.59

Heel pad syndrome

Inflammation of the heel pad between the calcaneus and the skin of the heel is also called superficial plantar fasciitis.60 The heel pad (Fig. 58.16) consists of fatty tissue and elastic fibrous tissue, enclosed within compartments formed by fibrous septa; these connect the skin of the heel with the calcaneal periosteum. The fat pad acts as a shock absorber.61 It can become inflamed after a direct blow or repeated minor injuries.62 The pain is felt all over the posterior part of the sole, especially during weight bearing.

Examination shows nothing in particular except uniform tenderness over the whole inferior surface of the heel. It was recently demonstrated that the affected heel pad in plantar heel pain syndrome was stiffer under light pressure than the heel pad on the painless side, and it was hypothesized that this was caused by the changed nature of chambered adipose tissue.63

Treatment

The patient lies prone, with the knee flexed at a right angle. The physician stands at the foot and encircles the heel with one hand. A 10 mL syringe is filled with procaine 0.5% and fitted to a needle 5 cm long. The needle is thrust in horizontally between calcaneus and skin (Fig. 58.17). The tip of the needle is then pushed in for some centimetres until it lies at the centre of the heel. The solution is injected there and diffuses over the whole area, forming a large, tense swelling. Significant pressure is needed to force in the last millilitre.

Fig 58.17 Injection in heel pad syndrome.

Subcutaneous bursitis

There is no anatomical bursa between the posterior aspect of the calcaneus and the skin, but in some circumstances a bursa may form, particularly when narrow and ill-fitting shoes are worn, and especially if they are curved in at the upper posterior edge.64 Friction of the hard border against the calcaneus results in an adventitious bursa. Chronic irritation will thicken the walls of the bursa and also the overlying skin. Palpation reveals a very tender spot at the posterior and upper surface of the calcaneus or at the lower extent of the Achilles tendon. The bursa is usually visibly inflamed and may contain some fluid. An excessive prominence of the bursal projection on the posterosuperior aspect of the calcaneus, in combination with a swollen and painful bursa, is called Haglund’s disease.65

The initial treatment is to alter the back of the shoe and introduce a rubber pad at the lower half of the back of the calcaneus, which keeps the upper half away from the pressing edge. If this does not succeed, the bursa can be drained by aspiration, followed by infiltration of 10 mg of triamcinolone. If such conservative treatment does not succeed, excision may be advised. The results of surgery are satisfactory, provided adequate bone has been resected.66,67

Ligamentous disorders – ankle sprains

‘Sprained ankle’ is the general name for a variety of traumatic lesions to the posterior segment of the foot. It is a very common sports injury. Several conditions are so described, varying from a simple strain of the ligaments to avulsion fractures and fracture–dislocations. Sometimes only one structure is injured, and sometimes several.68

Sprained ankles have been classified according to the causative stress (varus–valgus), the tissue damaged (ligament, tendon or bone) or the degree of damage (grade I, II or III) and the time elapsed since the causative accident (acute, subacute or chronic) (Box 58.1 and Tables 58.3 and 58.4).

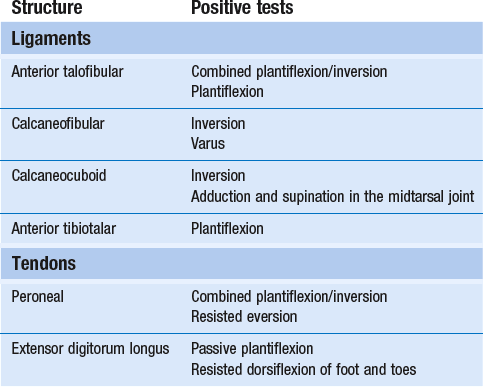

Table 58.3

Classification of ankle sprain according to time since accident

| Stage | Time |

| I Traumatic inflammation | 24–48 hours |

| II Repair period | 48 hours to 6 weeks |

| III Adherent scar tissue | > 6 weeks |

Table 58.4

Classification of ankle sprain by severity of lesion

| Grade71 | Lesion |

| I | Elongation of ligaments without macroscopic rupture |

| II | Partial and macroscopic ligamentous rupture |

| III | Complete ligamentous rupture |

Inversion sprain

Lateral ankle sprain injury is the most common acute sport trauma, and accounts for about 14% of all sport-related injuries.72 It is also reported to be the most common injury in college athletics in the United States.73 Athletes involved in soccer, basketball, volleyball and long-distance running are especially plagued by these injuries.74–76

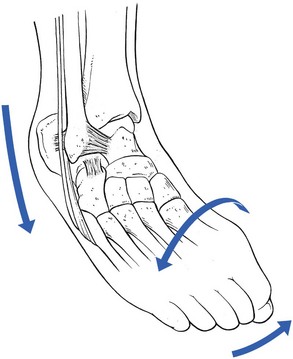

Mechanism

The origin of an inversion sprain is usually an indirect force produced against an inverted and plantiflexed foot, when the weight of the body forces the talus to rotate77 and twists the forefoot into supination and adduction. Hirsch and Lewis78 demonstrated that a rotational force of only 5–8 kg can produce a rupture of the anterior talofibular ligament.

The site of the lesion will depend largely on the degree of plantiflexion during inversion79,80 (Fig. 58.19):

• If the ankle is in the neutral position or slightly dorsiflexed during the excessive varus movement, the calcaneofibular ligament is damaged.81

• If the ankle is plantiflexed during the varus stress, the talus becomes involved in the movement and undergoes a medial rotation. This imposes the greatest stress between talus and fibula, and the anterior talofibular ligament becomes stretched.

• When the ankle and subtalar joints undergo indirect violence and the midtarsal joints and the forefoot are also twisted into full plantiflexion, with supination and adduction, the stress tends to fall on more distally localized structures such as the calcaneocuboid ligament, the insertion of the short peroneal tendon at the fifth metatarsal bone or the cuboid–fifth metatarsal joint.

• During complete plantiflexion of the ankle, with slight or no varus movement, the anterior tibiotalar ligament or the tendons of the extensor digitorum longus may be damaged.

Most authors only mention the talofibular and calcaneofibular ligaments.82,83 Very often, however, lesions of the calcaneocuboid ligament and tendinous lesions of the peronei and the long extensor of the toes result from an ankle sprain.

It is very important to note that, in most cases of sprained ankle, a combination of lesions occurs. The commonest association is a sprain of the fibular collateral ligament together with the calcaneocuboid ligament. Injury to all these structures may be correctly described by the patient as a ‘sprained ankle’. It is important to realize that, after a so-called varus sprain, not only ligamentous but also osseous lesions can occur. The most frequent lesions are fractures of both malleoli (Fig. 58.20): at the lateral malleolus a traction fracture, and at the medial malleolus a compression fracture. An avulsion fracture of the base of the fifth metatarsal is also not uncommon. It is obvious that, if history or examination suggests a fracture, a plain radiograph must be taken.

Natural history

It has been well established that the alignment of the collagen fibres in the scar is anarchic and disorderly if insufficient external stimulus is applied to the healing tissue. Some tension to the granulation is necessary to improve and accelerate the development of the fibrillary network into orderly layers.84 Immobilization leads to a scar that is adherent to capsule and bone. The sprained ankle then proceeds to a chronic stage: prolonged disability for several months. Sometimes the patient never recovers, unless the adhesions are ruptured by manipulation.

The discussion of diagnosis and treatment of ankle sprains follows the natural history sequence:

• First or acute stage: traumatic reaction immediately following the trauma – the first 24–48 hours.

• Second or subacute stage: traumatic reaction disappears; period of repair – from the second day to 6 weeks.

• Third or chronic stage: the scar has definitely formed; if there are adhesions, permanent disability results after 6 weeks to 2 months.

Diagnosis

Acute stage

• To detect serious lesions in recent ankle sprains, some ‘warning signs’ are built into the history and the clinical tests. These make it possible to identify cases of sprained ankle that have a high risk of complications: avulsion fractures, malleolar fractures, fractures of the fifth metatarsal base, haemarthrosis and total ruptures of the lateral ligaments.

• Localization of the site of the lesion can be deduced from the pattern that emerges when passive and resisted movements are tested. Once the site of the sprain has been identified by clinical examination, tenderness of the appropriate structures can be sought. (It is important to make the diagnosis purely by inference from studying the clinical tests and not by palpation. In recent cases, oedema and generalized tenderness are often so gross that palpation does not yield reliable information.)

The patterns of acute ligamentous and tendinous disorders are given in Table 58.5.

In combined lesions (two or more ligaments, or a ligament and a tendon), the clinical examination may be more puzzling. The information that emerges during the standard examination is summarized in Table 58.6.

Table 58.6

Summary of the diagnosis of recent inversion sprains

| Positive test | Lesion | Warning sign |

| Tiptoe rising | Peroneal tendons | Not possible: fractures of malleolus or 5th metatarsal |

| Plantiflexion Dorsiflexion |

Anterior talofibular/calcaneocuboid ligament | A capsular pattern: haemarthrosis in the ankle |

| Varus Valgus Mortice |

Calcaneofibular ligament | Excessive movement: total rupture Lateral pain: lateral avulsion fracture of the fibula Medial pain: medial compression fracture |

| Plantiflexion/inversion Plantiflexion/eversion |

All lateral ligaments and peroneal tendons | Excessive movement: total rupture Lateral pain: lateral avulsion fracture of the fibula |

| Plantiflexion Dorsiflexion Pronation |

Calcaneocuboid ligament | |

| Supination Abduction |

Calcaneocuboid ligament | |

| Adduction | Calcaneocuboid ligament | |

| Resisted plantiflexion | Peroneal tendons | |

| Resisted dorsiflexion Resisted inversion |

Tendons of extensor digitorum longus | |

| Resisted eversion | Peroneal tendons | Weakness: avulsion fracture of 5th metatarsal |

Technical investigations: radiography

Radiography is widely used in the assessment of inversion ankle injuries and accounts for about 10% of all radiographic examinations performed in accident departments.88 However, the predictive value of a plain radiograph examination in relation to fractures is rather poor when clinical warning signs are absent.89–91 For this reason, decision rules for plain X-rays have been developed – the so-called ‘Ottawa rules’. A plain X-ray of the ankle and foot should be requested if the patient is over 60 years of age or there is localized bone tenderness of the posterior edge or tip of either malleolus, or the patient is unable to bear weight immediately after the injury.92 This rule is 100% sensitive and 40.1% specific for detecting malleolar fractures and would allow a reduction of 36% of ankle radiographic series ordered.93,94

In order to diagnose complete rupture, other radiological procedures have been suggested: stress radiography (evaluation of talar tilt), ultrasound and MRI.95

• Stress radiography: talar tilt (the angle between the inferior border of the tibia and the superior edge of the talus, during varus stress) depends not only on the degree of ligamentous rupture but also on the use of anaesthesia,96 the degree of applied force and the direction of the X-ray beam. The sensitivity and selectivity of stress pictures are seriously questioned.97,98

• Ultrasound: this has been advocated for the evaluation of acute ankle ligament injuries because it allows for non-invasive and dynamic assessment of the ankle.99 However, ultrasound is highly dependent on equipment and operator skill level.

• MRI scans: these are not typically indicated for acute ankle sprains, except to elucidate associated conditions (detection of talar dome injuries).100 It is also important to note that approximately 30% of asymptomatic patients undergoing MRI have abnormal anterior talofibular ligaments.101

In our opinion, plain radiographs are advised only if the signs warrant them. Stress radiography, ultrasound and MRI should not be performed because their diagnostic and prognostic values are poor. Furthermore, because the majority of severe (grade III) ankle sprains may be treated non-operatively and, if residual instability occurs, late reconstruction achieves satisfactory results,102 early detection of severe grade III lesions by means of expensive and potentially dangerous investigations is obsolete.

Clinical examination (Table 58.7 and Box 58.2)

Adhesions

Table 58.7

Patterns of ligamentous and tendinous lesions in chronic inversion sprains

| Lesions of the: | Findings |

| Talofibular ligament | Passive plantiflexion–inversion: painful, slightly limited, tight end-feel |

| Midtarsal tests: negative | |

| Resisted movements: negative | |

| Calcaneocuboid ligament | Passive plantiflexion–inversion: painful, slightly limited, tight end-feel |

| Passive midtarsal supination: painful | |

| Resisted movements: negative | |

| Calcaneofibular ligament | Passive varus: painful |

| Peroneal tendon | Passive plantiflexion–inversion: painful |

| Midtarsal tests: negative | |

| Resisted eversion: positive | |

| Extensor digitorum tendon | Passive plantiflexion–(inversion): painful |

| Midtarsal tests: negative | |

| Resisted dorsiflexion: positive |

Persistent tendinitis

In this case, passive plantiflexion–inversion movement is also painful but the end-feel is normal. Pain during resisted eversion suggests that the peroneal tendons are at fault.103,104 Painful resisted dorsiflexion of foot and toes is caused by inflammation of the extensor digitorum longus tendons.

Treatment

Nowadays, it is generally accepted that ‘functional treatment’ with early mobilization and weight bearing and neuromuscular training exercises is the treatment of choice in grade I and grade II sprains.105–109 This approach achieves much better results than treatment with plaster immobilization.110–116 Early surgery may claim equally good results in the short term but long-term studies clearly demonstrated much better results when early mobilization was used.98,117,118 Other prospective and randomized studies also showed the best results with early functional treatment.119–121

For grade III ankle sprain, the treatment remains more controversial. Some surgeons recommend surgical repair142 while others favour non-operative conservative treatment.143 Recent research indicates that, even for total ruptures of the lateral ligaments of the ankle, the treatment of choice is still functional rehabilitation. Several prospective studies122,123 and meta-analyses124,125 showed that early functional treatment provided the fastest recovery of ankle mobility, and the earliest return to work and physical activity, without affecting late mechanical stability. A prospective and randomized study on 85 patients with acute grade II or grade III lateral ligament ruptures concluded that functional treatment was free from complication, resulted in shorter sick leave and facilitated an earlier return to sports than did surgery.126,127 Furthermore, secondary surgical repair, even years after an injury, has results comparable to those of primary repair,128,129 so even competitive athletes can receive initial conservative treatment.130

Early mobilization

The problem can be solved in two ways:

• Abolish the inflammation and pain as soon as possible, so that the patient can start mobilizing exercises (passive or active). This can be done via local infiltration of triamcinolone into the sprained structures. A small amount of steroid suffices, with no danger of causing permanent weakness of the ligament.

• Move the ligament over the (stationary) joint: Cyriax used to say: ‘If the joint cannot be moved in relation to the ligament, since pain and inflammation force the joint in muscle spasm, it will probably be possible to move the ligament in relation to the joint.’ The relative movement is the same, as is the mechanical stimulus to the regenerating fibrils. This can be achieved by gentle passive movements at the developing scar. This is the reasoning behind deep transverse friction applied to the sprained ankle.131

Treatment procedures

The treatment chosen depends on the stage of the lesion (Box 58.4).

Acute stage: first 2 days

Sometimes simple strapping in slight valgus is applied, which can give the patient confidence. It is also possible that the tape brings on a ‘musculocutaneous reflex’, whereby proprioception of the ankle is activated and so prevents an early recurrence of the sprain.107,132 Strapping must be loose enough to enable the patient to walk and to move the ankle as much as possible.

Treatment techniques

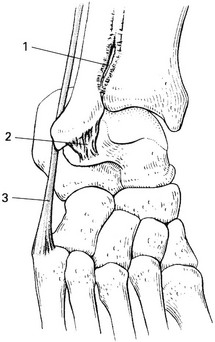

Technique: infiltration of the fibular extent of the talofibular and calcaneofibular ligament![]()

The injection technique is the same for both ligaments.

The patient lies supine on the couch, with the lower limb in internal rotation to bring the lateral malleolus uppermost. The foot must be held in as much plantiflexion and inversion as possible to make the lateral side accessible by the needle. After removing most of the oedema, tenderness is palpated along the inferior border of the malleolus and a line is defined from end to end. A 2 mL syringe is filled with triamcinolone, mixed with some local anaesthetic. A thin needle, 3 cm long, is fitted and inserted at a point 2 cm distal from the edge of the fibula. The needle is now moved almost parallel to the ligament, in the direction of the fibular edge (Fig. 58.21). A series of small droplets is injected from end to end at the ligamentoperiosteal insertion.

Technique: infiltration of the calcaneocuboid ligament

With one hand, the forefoot is supinated and adducted to bring the ligament under some tension. Tenderness along the ligament is sought in the following manner. The therapist places the interphalangeal joint of the thumb on the base of the fifth metacarpal bone and aims in the direction of the midpoint between the two malleoli. The tip of the thumb now lies exactly on the lateral calcaneocuboid ligament (Fig. 58.22a). The line of tenderness along the ligament is marked from end to end. A 2 mL syringe is filled with steroid suspension and fitted to a fine needle, 2 cm long. The needle is thrust in at the lateral border of the ligament (Fig. 58.22b). It is first moved to the calcaneal extent, where a series of droplets is placed along the ligamentoperiosteal border. The infiltration is made when the needle touches bone. Once the calcaneal border has been infiltrated, the needle is withdrawn slightly and pushed on to the cuboid border, where the same procedure is repeated.

Technique: deep friction to the fibular extent of the talofibular ligament![]()

The index finger of the ipsilateral hand, reinforced by the middle finger, is now placed on the site of the lesion. To reach the exact localization under the fibula, the forearm must be pronated, so the pressure will be upwards and inwards and the ligament is pressed between finger and bone. The thumb is placed proximal to the medial malleolus to give counterpressure during the massage (Fig. 58.23).

More thorough friction must be applied in the subacute stage.

Technique: deep friction to the talar extent of the talofibular ligament![]()

The position of the patient’s foot is the same as in the previous technique. The therapist uses the contralateral hand to force the foot slightly into plantiflexion and inversion in order to stretch the ligament. The neck of the talus is sought and the talar insertion of the ligament identified. The tip of the index finger of the other hand, reinforced by the middle finger, is placed on the talar extent (Fig. 58.24). The pressure is directed purely medially to the bone, so the forearm is not pronated. Friction is given by drawing the hand to and fro over the ligament. The thumb placed at the medial side of the foot acts as a fulcrum. The sweep will not be as large as in the previous technique because the talar extent of the ligament is much less.

Technique: deep friction to the fibular extent of the calcaneofibular ligament

The patient lies supine. The therapist sits at the distal end of the foot and fixes the heel in varus position with the ipsilateral hand. The index finger of the contralateral hand, reinforced by the middle finger, is placed under the fibular tip. The thumb is held at the medial malleolus so as to give counterpressure (Fig. 58.25). The friction is imparted by a flexion–extension movement at the wrist.

Technique: deep friction to the calcaneocuboid ligament

The patient lies face upwards, with the lower limb extended and in medial rotation. In this position, the outer border of the foot faces upwards. The ligament is palpated by using the technique explained above (see Fig. 58.22a). To check the correct position, the patient is asked to contract the peroneal tendons, which should lie just plantar to the fingertip.

The therapist sits at the inner side of the foot, facing its medial aspect. The foot is steadied with the contralateral hand, which forces the forefoot into adduction and supination. This brings the calcaneocuboid joint to prominence and stretches the ligament. The index finger of the other hand, reinforced by the middle finger, is placed on the joint line at the tender point (Fig. 58.26).

Fig 58.26 Friction to the calcaneocuboid ligament.

Technique: manipulation of adherent lateral ligaments

The patient lies supine on a high couch, the leg extended. The manipulator stands facing the patient’s foot, grasps the heel with the ipsilateral hand and forces it into full varus by an abduction movement of the arm. The dorsum of this hand will remain on the couch during the whole procedure. The contralateral hand is now placed on the dorsum of the foot, whereby the fingers curl round the shaft of the first metatarsal bone and the heel of the hand rests on the lateral border of the foot (Fig. 58.27).

Fig 58.27 Manipulation of adherent lateral ligaments: start of manipulation (a) and end of manipulation (b).

• The hand presses the foot downwards to the floor, which evokes plantiflexion.

• If the manipulator exerts greater pressure at the outer border of the foot, it is forced into inversion.

• An adduction movement in the foot is now obtained, when the heel of the manipulating hand is brought inwards, pivoting around the fingers at the inner side of the forefoot.

There are a number of contraindications to manipulation (Box 58.5).

Recurrent varus sprain – instability

Instability at the ankle, resulting in repeated minor sprains, may have different causes (Fig. 58.28):

• A ruptured distal tibiofibular ligament, with a so-called unstable mortice.

• A permanent lengthening of the anterior talofibular ligament, with an anteroposterior instability of the ankle joint.

• Proprioceptive deficits secondary to neurological injury to ankle ligaments and capsule. As a result, the peroneal muscles are brought into play too slowly to prevent further sprains when the ankle starts turning over.14,15

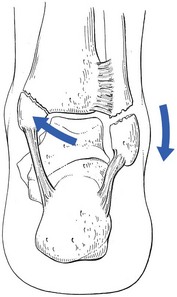

The unstable mortice

The common complaint is an ‘unstable ankle’ after a previous sprain. The patient finds that the foot turns over easily, often with an audible click and momentary severe pain in the ankle. The pain does not last very long and, after a few moments, walking can continue. The ankle merely feels sore for a couple of days.133

The diagnosis can be confirmed by radiography. If the radiograph is taken during strong varus movement, widening of the joint space between the tibia and fibula is seen.134

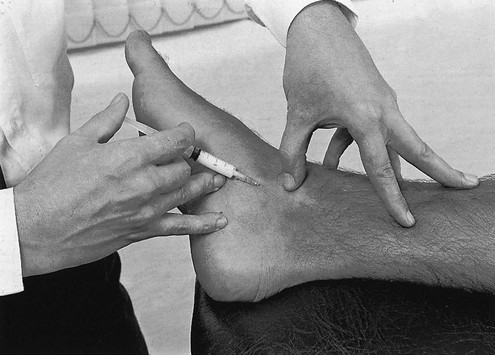

Treatment: sclerosing injections

To make the injection easier, it helps to measure on an anteroposterior radiograph the distances between the tip of the lateral malleolus and the articular surface of the tibia, together with the respective widths of tibia and fibula (Fig. 58.29).

Ligamentous insufficiency of the anterior talofibular ligament

Routine clinical examination shows nothing, except probably a greater range of inversion movement.

The anterior drawer test can be used to demonstrate a rupture or elongation of the anterior talofibular ligament.135

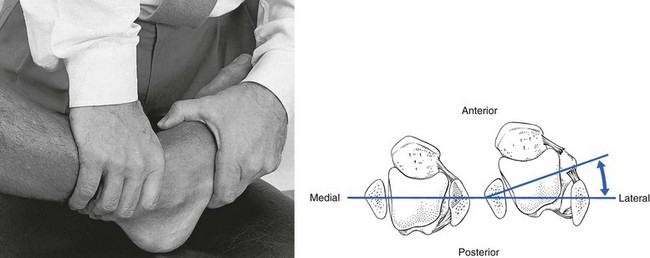

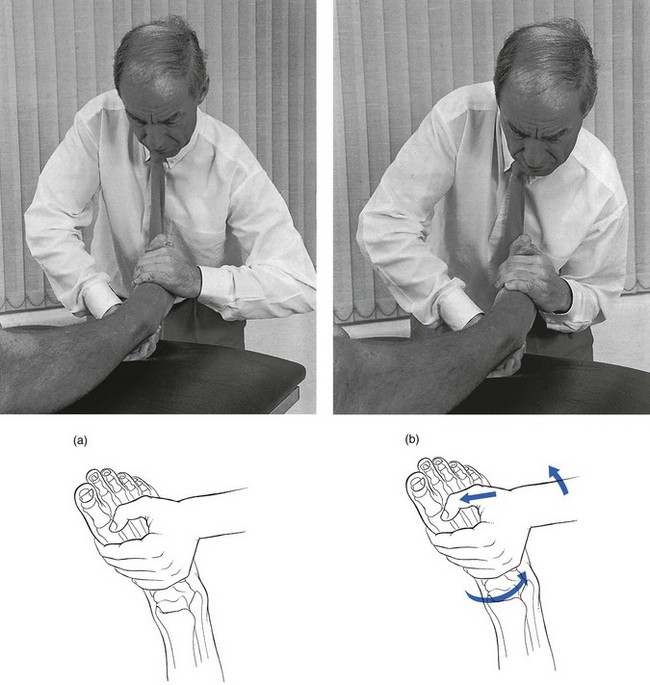

Diagnostic technique: anterior drawer test136–138

The ankle is held in slight plantiflexion. The examiner stands at the opposite side and stabilizes the patient’s lower leg with the ipsilateral hand. The contralateral hand encircles the foot and displaces the foot forwards. The lateral margin of the trochlea tali is thus shifted forwards in relation to the lateral malleolus (Fig. 58.30). It is important to notice that there is not only a forward gliding but also a medial rotation of the talus around a vertical axis at the medial malleolus.

As the anterior talofibular ligament is tense in all plantiflexion positions of the ankle, this anterior movement will only be possible if the ligament is not intact. The movement of the talus can be seen and felt. Often, a depression between talus and malleolus is noticed when the talus is moved forwards (Fig. 58.31). If a positive anterior drawer sign is present in a patient with recurrent ankle sprains or the patient fears the ankle ‘giving away’, a lax anterior talofibular ligament must be blamed for the symptoms.139

However, the reverse does not hold because only half of the patients with a positive anterior drawer sign report symptoms of ankle instability. The reason for this is probably compensation for the ligamentous laxity by muscle power and a good proprioceptive reflex.136 Therefore an anterior drawer test is never performed during the standard examination but only when the history warrants it.

Treatment

Conservative treatment of this form of instability consists of proprioceptive training, so that a good reflex will replace the function of the insufficient ligament. Mechanical devices designed to prevent ankle sprain during high-risk sporting activities (e.g. soccer, basketball) are: wrapping the ankle with tape or cloth, orthoses, high-top shoes or some combination of these methods. Appropriately applied braces, tape or orthoses should not adversely affect performance.140–143

If necessary, surgical repair of the torn ligaments may be advised.144,145 The results of late surgical repair are good.146,147

Functional instability

Cyriax148 first introduced the concept of functional instability in 1954 and experimental support was provided by Freeman in 1965.149,150

This concept views instability after an ankle sprain as being merely the result of a failure of the muscles of leg and ankle to afford active protection, rather than the result of rupture or elongation of the lateral ligaments.151,152 The sprain causes neurological damage at ligaments and capsule, which results in a prolonged propriosensory reflex. The increase in the peroneal reaction time is then responsible for inadequate protection against further sprain.153,154 However, arthromuscular reflex can be trained by movement and by coordination exercises on a ‘wobble board’.155,156

The re-education process is started on a see-saw block or a tilting board curved in one plane. While maintaining equilibrium on one leg, the patient tries to prevent either end of the block from touching the floor. The next step in regaining proprioception is training on a ‘wobble board’, first in a standing position, and later with tiptoeing and jumping or with some weights added to the wobble board.157

Differential diagnosis of instability

• If there is a history of previous sprain, apart from chronic peroneal tendinitis, the differential diagnosis is a chronic ligamentous adhesion (Table 58.8).

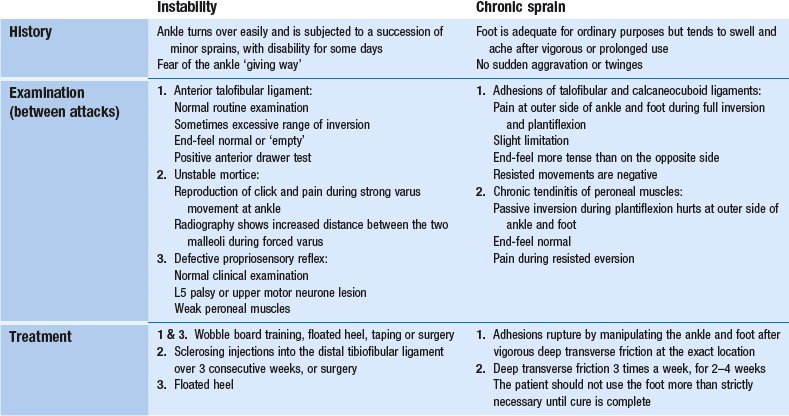

Table 58.8

Differential diagnosis and treatment of recurrent disability at the outer side of the foot

• If there is no clear history of previous ankle sprains, instability must be differentiated from loose bodies in the ankle and subtalar joints, ‘snapping peroneal tendon’, chronic peroneal tendinitis and jumper’s sprain.

Eversion sprain

Mechanism

The deltoid ligament is strong. The position of the ankle and foot is such that excessive eversion movement does not take place unless the patient already stands with a valgus deformity at the heel. Alternatively, a strong valgus movement can produce bone damage rather than a ligamentous lesion. The deltoid ligament is so strong that eversion injury tends to cause avulsion of the tibial malleolus rather than tearing of the ligament.158

Treatment

Massage is totally ineffective in this condition.

A 2 mL syringe is filled with 20 mg of triamcinolone and fitted to a thin needle, 2.5 cm long. A point is chosen about 2 cm below the medial malleolus. The needle is inserted here and pushed upwards through the ligament until it hits bone (Fig. 58.32). By means of a series of partial withdrawals and reinsertions, droplets of the suspension are injected along the affected extent of the ligamento-osseous junction, each time with the needle making contact with bone. As the deltoid ligament is a thick structure, the infiltrations should be made superficially and deeply.

Fig 58.32 Infiltration of the deltoid ligament.

For a comprehensive table summarizing the differential diagnosis of lesions at the heel and ankle, see online chapter Differential diagnosis of lesions at the heel and ankle.

References

1. Dieppe, PA, Calvent, P. Crystals and Joint Disease. London: Chapman & Hall; 1982.

2. Sijbrandij, FS, van Gils, AP, Louwerens, JW, de Lange, EE, Posttraumatic subchondral bone contusions and fractures of the talotibial joint: occurrence of ‘kissing’ lesions. Am J Roentgenol. 2000;175(6):1707–1710. ![]()

3. Pearce, DH, Mongiardi, CN, Fornasier, VL, Daniels, TR, Avascular necrosis of the talus: a pictorial essay. Radiographics. 2005;25(2):399–410. ![]()

4. Trauth, J, Bläsius, K, Die Talusnekrose und ihre Behandlung. Akt Traumatol 1988; 18:152–156. ![]()

5. Carpenter, B, Motley, T, The role of viscosupplementation in the ankle using hylan G-F 20. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2008;47(5):377–384. ![]()

6. Mink, AJF, ter Veer, HJ, Vorselaars, JAC. Extremiteiten, Functie-onderzoek en manuele therapie. Utrecht/Antwerp: Bohn Scheltema & Holkema; 1990.

7. Palladino, SJ, Chan, R, Adhesive capsulitis of the ankle. J Foot Surg. 1987;26(6):484–491. ![]()

8. Berndt, AL, Harty, M, Transchondral fractures (osteochondritis dissecans) of the talus. J Bone Joint Surg. 1958;41A(6):988–1016. ![]()

9. Zinman, C, Wolfson, N, Reis, ND, Osteochondritis dissecans of the dome of the talus; computed tomography scanning in diagnosis and follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg. 1988;70A(7):1017–1019. ![]()

10. McMurray, TP. Footballer’s ankle. J Bone Joint Surg. 1950; 32B:68–69.

11. Lohrer, H, Seltene Ursachen und Differentialdiagnosen der Achillodynie. Sportverletz-Sportschaden. 1992;5(4):182–185. ![]()

12. Hintermann, B, Holzach, P, Die Bursitis subachillea – eine biomechanische Analyse und Klinische Studie. Z Orthop Ihre Grenzgeb. 1992;130(2):114–119. ![]()

13. Frey, C, Rosenberg, Z, Shereff, MJ, The retrocalcaneal bursa: anatomy and bursography. Foot Ankle 1992; 13:203–207. ![]()

14. Hardaker, TW, Jr., Foot and ankle injuries in classical ballet dancers. Orthop Clin North Am 1989; 20:621–627. ![]()

15. Quick, R, Ballet injuries; the Australia experience. Clin Sports Med 1983; 2:507. ![]()

16. Demarais, Y. Lésions articulaires micro-traumatiques du pied chez le danseur. Sci Sport. 1986; 1:331–361.

17. Maquirriain, J, Posterior ankle impingement syndrome. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2005;13(6):365–371. ![]()

18. Johnson, RP, Collier, BD, Carrera, GF, The os trigonum syndrome. Use of bone scan in the diagnosis. J Trauma 1984; 24:761. ![]()

19. Karasick, D, Schweitzer, ME, The os trigonum syndrome: imaging features. Am J Roentgenol. 1996;166(1):125–129. ![]()

20. Bureau, NJ, Cardinal, E, Hobden, R, Aubin, B, Posterior ankle impingement syndrome: MR imaging findings in seven patients. Radiology. 2000;215(2):497–503. ![]()

21. Rathur, S, Clifford, PD, Chapman, CB, Posterior ankle impingement: os trigonum syndrome. Am J Orthop. 2009;38(5):252–253. ![]()

22. Martin, BF, Posterior triangle pain: the os trigonum. J Foot Surg. 1989;28(4):312–318. ![]()

23. Parker, JCH, Hamilton, WG, Patterson, AH, Rawles, JG, The anterior impingement syndrome of the ankle. J Trauma 1980; 20:895–898. ![]()

24. Kleiger, B, Anterior tibial talar impingement syndrome in dancers. Foot Ankle 1982; 3:69. ![]()

25. Van Dijk, CN, Marti, R, Besselaar, P. Aandoeningen van het bewegingsapparaat bij ballet. Geneeskd Sport. 1985; 18:52–63.

26. Branca, A, Di Palma, L, Bucca, C, et al, Arthroscopic treatment of anterior ankle impingement. Foot Ankle Int. 1997;18(7):418–423. ![]()

27. Renström, PA, Konradsen, L, Ankle ligament injuries. Br J Sports Med. 1997;31(1):11–20. ![]()

28. Jacobson, KE, Liu, SH, Anterolateral impingement of the ankle. J Med Assoc Ga. 1992;81(6):297–299. ![]()

29. Ferkel, RD, Karzel, RP, Del Pizzo, W, et al, Arthroscopic treatment of anterolateral impingement of the ankle. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(5):440–446. ![]()

30. Kim, SH, Ha, KI, Arthroscopic treatment for impingement of the anterolateral soft tissues of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg. 2000;82B(7):1019–1021. ![]()

31. Gare, BA, Fasth, A, The natural history of juvenile chronic arthritis: a population based cohort study. I. Onset and disease process. J Rheumatol 1995; 22:295–307. ![]()

32. Laurell, L, Court-Payen, M, Nielsen, S, et al, Ultrasonography and color Doppler in juvenile idiopathic arthritis: diagnosis and follow-up of ultrasound-guided steroid injection in the ankle region. A descriptive interventional study. Pediatr Rheumatol Online J. 2011;9(1):4. ![]()

33. Rompe, JD, Cacchio, A, Weil, L, Jr., et al, Plantar fascia-specific stretching versus radial shock-wave therapy as initial treatment of plantar fasciopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2010;92(15):2514–2522. ![]()

34. Gill, L, Kiebzak, G, Outcome of nonsurgical treatment for plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int 1996; 17:527–532. ![]()

35. Cornwall, MW, McPoil, TG, Plantar fasciitis: etiology and treatment. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29(12):756–760. ![]()

36. Quaschnick, MS, The diagnosis and management of plantar fasciitis. Nurse Pract. 1996;21(4):50–54. ![]()

37. Katoh, Y, Chao, EY, Morrey, BF, Objective technique for evaluating painful heel syndrome and its treatment. Foot Ankle 1983; 3:227. ![]()

38. Warren, BC, Anatomical factors associated with predicting plantar fasciitis in long distance runners. Med Sci Sports Exec 1984; 16:60. ![]()

39. Tsai, WC, Chiu, MF, Wang, CL, et al, Ultrasound evaluation of plantar fasciitis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2000;29(4):255–258. ![]()

40. Kamel, M, Kotob, H, High frequency ultrasonographic findings in plantar fasciitis and assessment of local steroid injection. J Rheumatol. 2000;27(9):2139–2141. ![]()

41. Theodorou, DJ, Theodorou, SJ, Kakitsubata, Y, et al, Plantar fasciitis and fascial rupture: MR imaging findings in 26 patients supplemented with anatomic data in cadavers. Radiographics 2000; 20:Spec:S181–S197. ![]()

42. Bassiouni, M, Incidence of calcaneal spurs in osteoarthrosis and rheumatoid arthritis, and in control patients. Ann Rheum Dis 1965; 24:490. ![]()

43. Powell, M, Post, WR, Keener, J, Wearden, S, Effective treatment of chronic plantar fasciitis with dorsiflexion night splints: a crossover prospective randomized outcome study. Foot Ankle Int. 1998;19(1):10–18. ![]()

44. Gill, LH, Kiebzak, GM, Outcome of nonsurgical treatment for plantar fasciitis. Foot Ankle Int. 1996;17(9):527–532. ![]()

45. Crawford, F, Atkins, D, Edwards, J. Interventions for treating plantar heel pain [Cochrane Review on CD-ROM]. Oxford: Cochrane Library, Update Software; 2002.

46. Ogden, JA, Alvarez, R, Levitt, R, et al, Shock wave therapy for chronic proximal plantar fasciitis. Clin Orthop 2001; 387:47–58. ![]()

47. Rompe, JD, Hopf, C, Nafe, B, Burger, R, Low-energy extracorporeal shock wave therapy for painful heel: a prospective controlled single-blind study. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1996; 115:75–79. ![]()

48. Buchbinder, R, Ptasznik, R, Gordon, J, et al, Ultrasound-guided extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fasciitis: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2002;288(11):1364–1372. ![]()

49. Greve, JM, Grecco, MV, Santos-Silva, PR, Comparison of radial shockwaves and conventional physiotherapy for treating plantar fasciitis. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2009;64(2):97–103. ![]()

50. Porter, MD, Shadbolt, B, Intralesional corticosteroid injection versus extracorporeal shock wave therapy for plantar fasciopathy. Clin J Sport Med. 2005;15(3):119–124. ![]()

51. Kane, D, Greaney, T, Bresnihan, B, et al, Ultrasound guided injection of recalcitrant plantar fasciitis. Am Rheum Dis. 1998;57(6):383–384. ![]()

52. Tsai, WC, Wang, CL, Tang, FT, et al, Treatment of proximal plantar fasciitis with ultrasound-guided steroid injection. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2000;81(10):1416–1421. ![]()

53. Davies, MS, Weiss, GA, Saxby, TS, Plantar fasciitis: how successful is surgical intervention? Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(12):803–807. ![]()

54. Bates, BT, Osternig, LR, James, MS, James, LS, Foot orthotic devices to modify selected aspects of lower extremity mechanics. Am J Sports Med 1979; 7:338. ![]()

55. Kwong, PK, Kay, D, Voner, RT, White, MW, Plantar fasciitis. Mechanics and pathomechanics of treatment. Clin Sports Med 1988; 7:119–126. ![]()

56. Du Vries, HL, Heel spur (calcaneal spur). Arch Surg 1957; 74:536–542. ![]()

57. Leach, RT, Herrick, S, Rupture of the plantaris fascia in athletes. J Bone Joint Surg 1978; 60A:537–539. ![]()

58. Ahstrom, JP, Spontaneous rupture of the plantar fascia. Am J Sports Med 1988; 16:306–307. ![]()

59. Kulund, DN. The Injured Athlete, 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1988.

60. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol. 1, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 8th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1982.

61. Jahss, MH, Michelson, JD, Desai, P, et al, Investigations into the fat pad of the sole of the foot: Anatomy and histology. Foot Ankle 1992; 15:233–242. ![]()

62. Bazzoli, AS, Pollina, FS. Heel pain in recreational runners. Phys Sportsmed. 1989; 17(2):55–61.

63. Tsai, WC, Wang, CL, Hsu, TC, et al, The mechanical properties of the heel pad in unilateral plantar heel pain syndrome. Foot Ankle Int. 1999;20(10):663–668. ![]()

64. Biedert, R, Beschwerden im Achillessehnenbereich. Aetiologien und therapeutische Überlegungen. Unfallchirurgie. 1991;94(10):531–537. ![]()

65. Stephens, MM, Haglund’s deformity and retrocalcaneal bursitis. Orthop Clin North Am. 1994;25(1):41–46. ![]()

66. Lehto, MU, Jarvinen, M, Suominen, P, Chronic Achilles peritendinitis and retrocalcanear bursitis. Long-term follow-up of surgically treated cases. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1994;2(3):182–185. ![]()

67. Sella, FJ, Caminear, DS, McLarney, EA, Haglund’s syndrome. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998;37(2):110–114. ![]()

68. Boruta, PM, Bishop, JO, Braly, WG, Tullos, HS, Acute lateral ankle ligament injuries: a literature review. Foot Ankle. 1990;11(2):107–113. ![]()

69. Fallat, L, Grimm, DJ, Saracco, JA, Sprained ankle syndrome: prevalence and analysis of 638 acute injuries. J Foot Ankle Surg. 1998;37(4):280–285. ![]()

70. van Dijk, CN, Molenaar, AH, Cohen, RH, et al, Value of arthrography after supination trauma of the ankle. Skeletal Radiol. 1998;27(5):256–261. ![]()

71. McConkey, JP. Ankle sprains, consequences and mimics. Med Sports Sci. 1987; 23:39–55.

72. Fong, DTP, Hong, Y, Chan, LK, et al, A systematic review on ankle injury and ankle sprain in sports. Sports Medicine 2007; 37:73–94. ![]()

73. Hootman, JM, Dick, R, Agel, J, Epidemiology of collegiate injuries for 15 sports: summary and recommendations for injury prevention initiatives. Journal of Athletic Training 2007; 42:311–319. ![]()

74. Maehlum, S, Daljord, OA, Acute sports injuries in Oslo: a one year study. Br J Sports Med 1984; 18:181–185. ![]()

75. Ekstrand, J, Tropp, H, The incidence of ankle sprains in soccer. Foot Ankle 1990; 11:41–44. ![]()

76. Chan, KM, Yuan, Y, Li, CK, et al, Sports causing most injuries in Hong Kong. Br J Sports Med 1993; 27:263–267. ![]()

77. Lindstrand, A. Lateral lesions in sprained ankle – a clinical and roentgenological study with special reference to the anterior instability of the talus. Sweden: Dissertation, Lund University; 1976.

78. Hirsch, C, Lewis, J, Experimental ankle-joint fractures. Acta Orthop Scand 1965; 36:408. ![]()

79. Stephens, MM, Sammarco, GJ, The stabilizing role of the lateral ligament complex around the ankle and subtalar joints. Foot Ankle 1992; 13:130–136. ![]()

80. Wright, IC, Neptune, RR, van den Bogert, AJ, Nigg, BM, The influence of foot positioning on ankle sprains. J Biomech. 2000;323(5):513–519. ![]()

81. Bennett, WF, Lateral ankle sprains. Part I: Anatomy, biomechanics, diagnosis, and natural history. Orthop Review 1994; 23:381–387. ![]()

82. Broström, L, Sprained ankles. I Anatomic lesions in recent sprains. Acta Chir Scand 1964; 128:483. ![]()

83. Prins, JG, Diagnosis and treatment of injury to the lateral ligament of the ankle. Acta Chir Scand 1978; 486. ![]()

84. Akeson, WH, Amiel, D, Abel, MF, et al, Effects of immobilization on joints. Clin Orthop 1987; 219:33. ![]()

85. van Enst, W. Distorsies van het enkelgewricht. Geneeskd Sport. 1968; 1:55–62.

86. Landeros, O, Frost, HM, Higgins, CC, Post-traumatic anterior ankle instability. Clin Orthop 1968; 56:169–178. ![]()

87. Frost, HM, Does the ligament injury require surgery. Clin Orthop 1974; 103:49. ![]()

88. De Lacey, GJ, Bradbrooke, S, Rationalising requests for X-ray examination of acute ankle injuries. BMJ 1979; 1587–1588. ![]()

89. Vargish, T, Clarke, WR, Young, RA, Jensen, A, The ankle injury. Indications for the selective use of X-rays. Injury 1983; 14:507–512. ![]()

90. Dunlop, MG, Beattie, TF, White, GK, et al, Guidelines for selective radiological assessment of inversion ankle injuries. BMJ 1986; 293:603–605. ![]()

91. Van Ray, JJAM, Zeegers, AVCM, Oostvogel, HJM, Van der Wekken, C, De waarde van het Röntgenonderzoek bij supinatieletsels van enkel en voet. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1990; 134:1541–1544. ![]()

92. Stiell, IG, Greenberg, GH, McKnight, RD, et al, Decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Refinement and prospective validation. JAMA. 1993;269(9):1127–1132. ![]()

93. Stiell, IG, Greenberg, GH, McKnight, RD, et al, A study to develop clinical decision rules for the use of radiography in acute ankle injuries. Ann Emerg Med. 1992;21(4):381–390. ![]()

94. Bachmann, LM, Kolb, E, Koller, MT, et al, Accuracy of Ottawa ankle rules to exclude fractures of the ankle and mid-foot: systematic review. BMJ. 2003;326(7386):417. ![]()

95. Oae, K, Takao, M, Uchio, Y, Ochi, M, Evaluation of anterior talofibular ligament injury with stress radiography, ultrasonography and MR imaging. Skeletal Radiol. 2010;39(1):41–47. ![]()

96. Hoogenband, CR, Moppes, FI, Clinical diagnosis, arthrography, stress examination and surgical girding after inversion trauma of the ankle. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1984; 103:115–119. ![]()

97. Sanders, HWA. Betekenis van röntgenologische onderzoeksmethoden voor de diagnostiek van (laterale) enkelbandlaesies. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1976; 120:2053–2058.

98. van Moppes, FI, van den Hoogenband, CR. Diagnostic and Therapeutic Aspects of Inversion Trauma of the Ankle Joint. Maastricht: Crouzen; 1982.

99. Guillodo, Y, Riban, P, Guennoc, X, et al, Usefulness of ultrasonographic detection of talocrural effusion in ankle sprains. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(6):831–836. ![]()

100. Magee, TH, Hinson, GW, Usefulness of MR imaging in the detection of talar dome injuries. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(5):1227–1230. ![]()

101. Saxena, A, Luhadiya, A, Ewen, B, Goumas, C, Magnetic resonance imaging and incidental findings of lateral ankle pathologic features with asymptomatic ankles. J Foot Ankle Surg. 2011;50(4):413–415. ![]()

102. Kitaoka, HB, Lee, MD, Morrey, BF, Cass, JR, Acute repair and delayed reconstruction for lateral ankle instability: twenty-year follow-up study. J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11(7):530–535. ![]()

103. DiGiovanni, BF, Fraga, CJ, Cohen, BE, Shereff, MJ, Associated injuries found in chronic lateral ankle instability. Foot Ankle Int. 2000;21(10):809–815. ![]()

104. Park, HJ, Cha, SD, Kim, HS, et al, Reliability of MRI findings of peroneal tendinopathy in patients with lateral chronic ankle instability. Clin Orthop Surg. 2010;2(4):237–243. ![]()

105. Linde, F, Hraas, I, Jurgensen, U, Madsen, I, Early mobilizing treatment in lateral ankle sprains. Scand J Rehabil Med 1986; 18:17–21. ![]()

106. Roycroft, S, Mantgani, AB, Treatment of inversion injuries of the ankle by early active management. Physiotherapy 1983; 69:355–356. ![]()

107. Freeman, MAR. The etiology and prevention of functional instability of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg. 1965; 47B:678–685.

108. Osborne, MD, Rizzo, TD, Jr., Prevention and treatment of ankle sprain in athletes. Sports Medicine 2003; 33:1145–1150. ![]()

109. Karlsson, J, Sancone, M, Management of acute ligament injuries of the ankle. Foot and Ankle Clinics 2006; 11:521–530. ![]()

110. Speeckaert, MTC, De behandeling van laterale enkelbandlaesies. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd 1978; 122:1612–1618. ![]()

111. Broström, L, Sprained ankles. Treatment and prognosis in recent ligament ruptures. Acta Chir Scand 1966; 132:537–550. ![]()

112. Rens van, THJG, Rupturen van de laterale enkelbanden; opereren of niet? Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1986;130(11):480–484. ![]()

113. Staples, OS, Result study of ruptures of lateral ligaments of the ankle. Clin Orthop 1972; 85:50–58. ![]()

114. Ruth, CJ. The surgical treatment of injuries of the fibular collateral ligament of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg. 1961; 43A:229–239.

115. Caro, D, Craft, IL, Howells, JB, Shaw, PC, Diagnosis and treatment of injury of lateral ligament of the ankle joint. Lancet 1964; ii:720–723. ![]()

116. Klein, J, Rixen, D, Tilling, T, Funktionelle versus Gipsbehandlung bei der frischen Aussenbandruptur des oberen Sprunggelenks. Unfallchirurgie 1991; 94:99–104. ![]()

117. Brink, PRG, Runne, WC, Wever, J, De functionele behandeling van rupturen van de laterale enkelband. Ned Tijdschr Geneeskd. 1988;132(15):672–676. ![]()

118. Klein, J, Hoher, J, Tilling, T, Comparative study of therapies for fibular ligament rupture of the lateral ankle joint in competitive basketball players. Foot Ankle 1993; 14:320–324. ![]()

119. Möller-Larsen, F, Wethelund, O, Jurik, AG, et al, Comparison of three different treatments for ruptured lateral ankle ligaments. Acta Orthop Scand. 1988;58(5):564–566. ![]()

120. Sommer, AM, Arza, D, Functional treatment of recent ruptures of the fibular ligament of the ankle. Int Orthop 1989; 13:157–160. ![]()

121. Konradsen, L, Holmer, P, Sondergaard, L, Early mobilizing treatment for grade III ankle ligament injuries. Foot Ankle. 1991;12(2):69–73. ![]()

122. Kaikkonen, A, Kannus, P, Jarvinen, M, Surgery versus functional treatment in ankle ligament tears. A prospective study. Clin Orthop 1996; 326:194–202. ![]()

123. Eiff, MP, Smith, AT, Smith, GE, Early mobilization versus immobilization in the treatment of lateral ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 1994;22(1):83–88. ![]()

124. Lynch, SA, Renstrom, PA, Treatment of acute lateral ankle ligament rupture in the athlete. Conservative versus surgical treatment. Sports Med. 1999;27(1):61–71. ![]()

125. Kerkhoffs, GM, Rowe, BH, Assendelft, WJ, et al, Immobilisation and functional treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2002; . ![]()

126. Karlsson, J, Eriksson, BI, Sward, L, Early functional treatment for acute ligamentous injuries of the ankle joint. Scand J Med Sci Sports. 1996;6(6):341–345. ![]()

127. Pijnenburg, AC, Bogaard, K, Krips, R, et al, Operative and functional treatment of rupture of the lateral ligament of the ankle. A randomised, prospective trial. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2003;85(4):525–530. ![]()

128. Peterson, L, Althoff, B, Renström, P, Reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle joint, Feb 1979.

129. Cass, JR, Morrey, BF, Katoh, Y, Chao, EY, Ankle instability: comparison of primary repair and delayed reconstruction after long-term follow-up study. Clin Orthop 1985; 198:110–117. ![]()

130. Safran, MR, Zachazewski, JE, Benedetti, RS, et al, Lateral ankle sprains: a comprehensive review part 2: treatment and rehabilitation with emphasis on the athlete. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999;31(7 suppl):S438–S447. ![]()

131. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol. II, Treatment by Manipulation, Massage and Injection, 11th ed. London: Baillière Tindall; 1984.

132. Larsen, E, Taping the ankle for chronic instability. Acta Orthop Scand 1984; 55:551–553. ![]()

133. Boytim, MJ, Fischer, DA, Neumann, L, Syndesmotic ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19(3):294–298. ![]()

134. Mulligan, EP, Evaluation and management of ankle syndesmosis injuries. Phys Ther Sport. 2011;12(2):57–69. ![]()

135. Dehne, E. Die Klinik der frischen und habituellen Adduktionssupinationsdistorsion des Fusses. Deutsch Z Chirurg. 1933; 242:40–61.

136. Broström, L, Sprained ankles. III. Clinical observations in recent ligament ruptures. Acta Chir Scand 1965; 130:560–569. ![]()

137. Castaing, J, Delplace, J, Entorses de la cheville. Intérêt de l’étude de la stabilité dans le plan sagittal pour de diagnostic de gravité. Recherche radiographique du tiroir astralgien antérieur. Rev Chir Orthop 1972; 58:51–63. ![]()

138. Laurin, C, Mathieu, J, Sagittal mobility of the normal ankle. Clin Orthop 1975; 108:534–550. ![]()

139. Karlsson, J, Eriksson, BI, Renstrom, PA, Subtalar ankle instability. A review. Sports Med. 1997;24(5):337–346. ![]()

140. Robbins, S, Waked, E, Factors associated with ankle injuries. Preventive measures. Sports Med. 1998;25(1):63–72. ![]()

141. Thacker, SB, Stroup, DF, Branche, CM, et al, The prevention of ankle sprains in sports. A systematic review of the literature. Am J Sports Med. 1999;27(6):753–760. ![]()

142. Quinn, K, Parker, P, de Bie, R, et al, Interventions for preventing ankle ligament injuries. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2000;(2). ![]()

143. Zinder, SM, Granata, KP, Shultz, SJ, Gansneder, BM, Ankle bracing and the neuromuscular factors influencing joint stiffness. J Athl Train. 2009;44(4):363–369. ![]()

144. St Pierre, R, Allman, F, Bassett, FH, et al, A review of lateral ankle ligamentous reconstruction. Foot Ankle 1982; 3:114–123. ![]()

145. Saltrick, KR, Lateral ankle stabilization. Modified Lee and Christman–Snook. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 1991;8(3):579–600. ![]()

146. Snook, GA, Christman, OD, Wilson, TC, Long-term results of the Christman–Snook operation for reconstruction of the lateral ligaments of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg 1985; 67A:1–7. ![]()

147. Colville, MR, Surgical treatment of the unstable ankle. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1998;6(6):368–377. ![]()

148. Cyriax, JH. Textbook of Orthopaedic Medicine, vol. I, Diagnosis of Soft Tissue Lesions, 2nd ed. London: Cassell; 1954.

149. Freeman, MAR, The etiology and prevention of functional instability of the foot. J Bone Joint Surg 1965; 47B:678–686. ![]()

150. Freeman, MAR, Instability of the foot after injuries to the lateral ligament of the ankle. J Bone Joint Surg 1965; 47B:669–677. ![]()

151. Hertel, J, Functional instability following lateral ankle sprain. Sports Med. 2000;29(5):361–371. ![]()

152. Konradsen, L, Olesen, S, Hansen, HM, Ankle sensorimotor control and eversion strength after acute ankle inversion injuries. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26(1):72–77. ![]()

153. Konradsen, L, Bohsen Ravn, J, Ankle instability caused by prolonged peroneal reaction time. Acta Orthop Scand. 1990;61(5):388–390. ![]()

154. Konradsen, L, Ravn, JB, Prolonged peroneal reaction time in ankle instability. Int J Sports Med. 1991;12(3):290–292. ![]()

155. Freeman, MAR, Coordination exercises in the treatment of the functional instability of the foot. Physiotherapy 1965; 51:393–395. ![]()

156. Tropp, H. Functional instability of the ankle joint. Linköping Sweden: University of Linköping Medical Dissertations; 1985.

157. Rozzi, SL, Lephart, SM, Sterner, R, Kuligowski, L, Balance training for persons with functionally unstable ankles. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 1999;29(8):478–486. ![]()

158. Hintermann, B, Knupp, M, Pagenstert, GI, Deltoid ligament injuries: diagnosis and management. Foot Ankle Clin. 2006;11(3):625–637. ![]()