Chapter 148 Treatment of Rheumatic Diseases

Pediatric Rheumatology Teams and Primary Care Physicians

The multidisciplinary pediatric rheumatology team (Table 148-1) offers coordinated services for children and their families. General principles of treatment include: early recognition of signs and symptoms of rheumatic disease with timely referral to rheumatology for prompt initiation of treatment; monitoring for disease complications and adverse effects of treatment; coordination of subspecialty care and rehabilitation services with communication of clinical information; and child and family–centered chronic illness care, including self-management support, alliance with community resources, partnership with schools, resources for dealing with the financial burdens of disease, and connection with advocacy groups. Planning for transition to adult care providers needs to start in adolescence. Central to effective care is partnership with the primary care provider, who helps coordinate care, monitor compliance with treatment plans, ensure appropriate immunization, monitor for medication toxicities, and identify disease exacerbations and concomitant infections. Communication between the primary care provider and subspecialty team permits timely intervention when needed.

Table 148-1 MULTIDISCIPLINARY TREATMENT OF RHEUMATIC DISEASES IN CHILDHOOD

| Accurate diagnosis and education of family |

Therapeutics

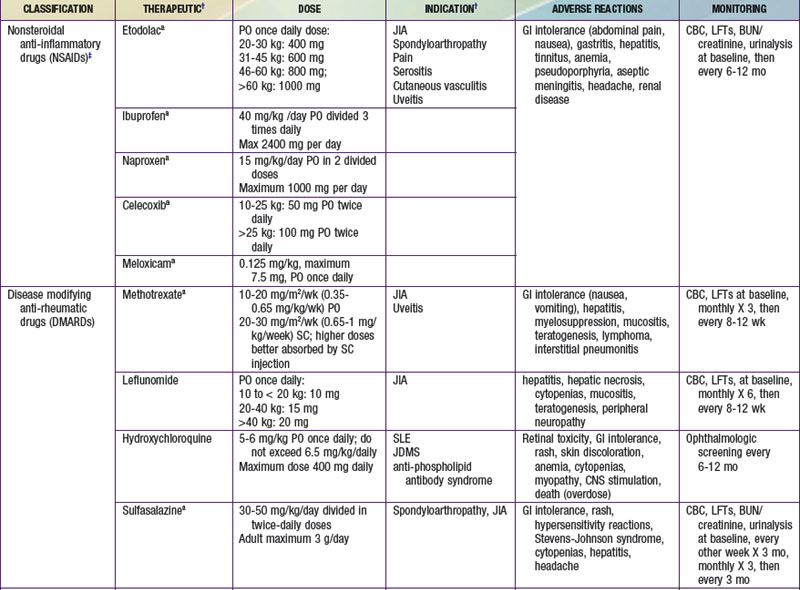

A key principle of pharmacologic management of rheumatic diseases is that early disease control, striving for induction of remission, leads to less tissue and organ damage with improved short- and long-term outcomes. Medications are chosen from broad therapeutic classes on the basis of diagnosis, disease severity, anthropometrics, and adverse effect profile. Many of therapeutics used do not have U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indications for pediatric rheumatic diseases. The evidence base may be limited to case series, uncontrolled studies, or extrapolation from use in adults. The exception is JIA, for which there is a growing body of randomized control trial evidence, particularly for newer therapeutics. Therapeutic agents used for treatment of childhood rheumatic diseases (Table 148-2) have various mechanisms of action, but all suppress inflammation. Both biologic and nonbiologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (DMARDs) directly affect the immune system. DMARDs should be prescribed by specialists. Live vaccines are contraindicated in patients taking immunosuppressive glucocorticoids or DMARDs. A negative test result for tuberculosis (purified protein derivative [PPD]) should be verified and the patient’s immunization status updated, if possible, before such treatment is initiated. Killed vaccines are not contraindicated, and annual injectable influenza vaccine is recommended in children with rheumatic diseases.

Nonbiologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

Biologic Disease-Modifying Antirheumatic Drugs

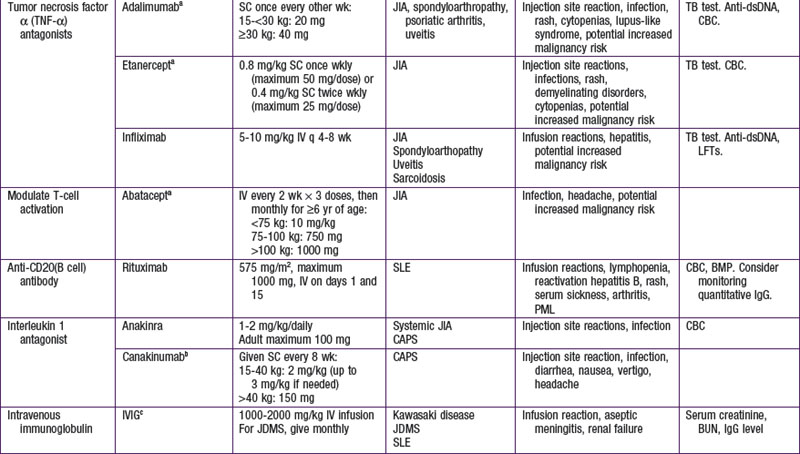

Biologic response–modifying drugs that target specific components of the immune system are becoming increasingly available for treatment of various rheumatic diseases. The initial biologic DMARDs targeted tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), a proinflammatory cytokine implicated in inflammatory arthritis. Subsequently, biologic therapeutics have been developed to target specific cytokines such as interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6 or to interfere with specific immune cell function through depletion of B cells or suppression of T-cell activation (Table 148-3).

Table 148-3 SUMMARY OF BIOLOGIC THERAPIES STUDIED IN JUVENILE IDIOPATHIC ARTHRITIS AND THEIR METHOD OF ACTION

| DRUG | METHOD OF ACTION |

|---|---|

| Etanercept | Soluble TNF p75 receptor fusion protein that binds to and inactivates TNF-α |

| Infliximab | Chimeric human/mouse monoclonal antibody that binds to soluble TNF-α and its membrane-bound precursor, neutralizing its action |

| Adalimumab | A humanized IgG1 monoclonal antibody that binds to TNF-α |

| Abatacept | Soluble, fully human fusion protein of the extracellular domain of (CTLA-4, linked to a modified Fc portion of the human IgG1. It acts as a co-stimulatory signal inhibitor by binding competitively to CD80 or CD86, where it selectively inhibits T-cell activation |

| Tocilizumab | A humanized anti–human IL-6 receptor monoclonal antibody |

| Anakinra | An IL-1 receptor antagonist (IL-1 RA) |

CTLA, cytotoxic T lymphocyte–associated antigen; Ig, immunoglobulin; IL, interleukin; TNF, tumor necrosis factor.

From Beresford MW, Baildam EM: New advances in the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis— 2: the era of biologicals, Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed 94:151–156, 2009.

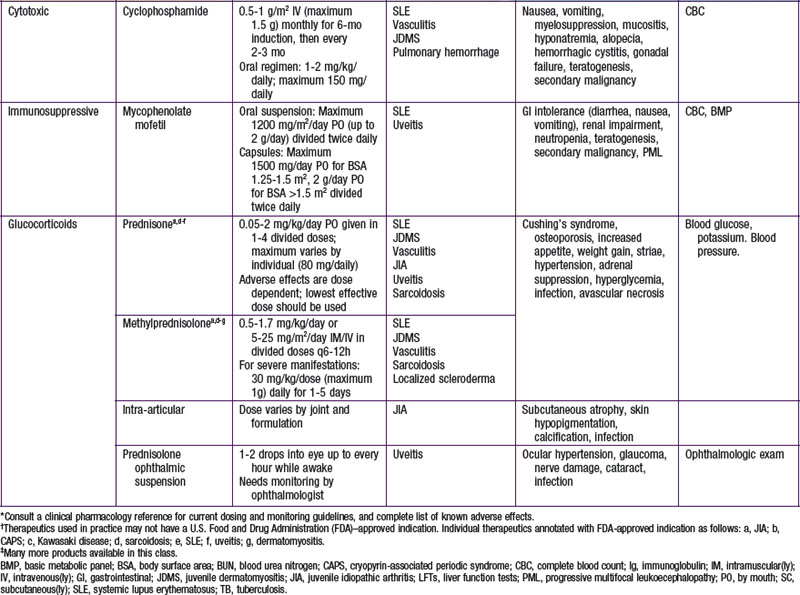

Cytotoxics

Other Drugs

Azathioprine is sometimes used to treat Wegener granulomatosis following induction therapy or to treat SLE. Cyclosporine has been used occasionally in the treatment of dermatomyositis on the basis of uncontrolled studies and is helpful in the treatment of macrophage activation syndrome complicating systemic JIA (Chapter 149). There are case reports describing the successful use of thalidomide, or its analog lenalidomide, as treatment for systemic JIA, inflammatory skin disorders, and Behçet disease. Several drugs commonly used in the past to treat arthritis are no longer part of standard treatment, including salicylates, gold compounds, and D-penicillamine.

Ardoin S, Schanberg LE. The management of pediatric systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Clin Pract Rheumatol. 2005;1:1-11.

Beresford MW, Baildam EM. New advances in the management of juvenile idiopathic arthritis—2: the era of biologicals. Arch Dis Child Educ Pract Ed. 2009;94:151-156.

Burgos-Vargas R, Vazquez-Mellado J, Pacheco-Tena C, et al. A 26 week randomized, double blind, placebo controlled exploratory study of sulfasalazine in juvenile onset spondyloarthropathies. Ann Rheum Dis. 2002;61:941-942.

Cleary AG, Murphy HD, Davidson JE. Intra-articular corticosteroid injections in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arch Dis Child. 2003;88:192-196.

. Clinical pharmacology [online database]. Tampa, FL, Gold Standard, 2009 http://www.clinicalpharmacology.com

Feldman BM, Rider LG, Reed AM, et al. Juvenile dermatomyositis and other idiopathic inflammatory myopathies of childhood. Lancet. 2008;371:2201-2212.

Gedalia A, Shetty AK. Chronic steroid and immunosuppressant therapy in children. Pediatr Rev. 2004;25:425-434.

Gürcan HM, Ahmed AR. Efficacy of various intravenous immunoglobulin therapy protocols in autoimmune and chronic inflammatory disorders. Ann Pharmacother. 2007;41:812-823.

Hashkes PJ, Laxer RM. Medical treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis. JAMA. 2005;294:1671-1684.

Lovell DJ, Ruperto N, Goodman S, et al. Adalimumab with or without methotrexate in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group; Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organisation. N Engl J Med. 2008;359:810-820.

McGonagh JE. Young people first, juvenile idiopathic arthritis second: transitional care in rheumatology. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;59:1162-1170.

Morgan SL, Oster RA, Lee JY, et al. The effect of folic acid and folinic acid supplements on purine metabolism in methotrexate-treated rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:3104-3111.

Navaneethan SD, Viswanathan G, Strippoli GF. Treatment options for proliferative lupus nephritis: an update of clinical trial evidence. Drugs. 2008;68:2095-2104.

Ruperto N, Murray KJ, Gerloni V, et al. A randomized trial of parenteral methotrexate comparing an intermediate dose with a higher dose in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis who failed to respond to standard doses of methotrexate. for the Pediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization. Arthritis Rheum. 2004;50:2191-2201.

Ruperto N, Lovell DJ, Quartier P, et al. Abatacept in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled withdrawal trial. Paediatric Rheumatology International Trials Organization; Pediatric Rheumatology Collaborative Study Group. Lancet. 2008;372(9636):383-391.

Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Koeller M, et al. New therapies for treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet. 2007;370:1861-1874.

Tolleson-Rinehart S, Morgan DeWitt E, Massie S, Pediatric Education for Drug Safety. Pharmacological treatment of juvenile idiopathic arthritis: a pediatric education for drug safety (PEDS) continuing education module. http://pedscme.unc.edu. Accessed May 1, 2008