4 Treatment of orthopaedic disorders

Orthopaedic treatment falls into three categories:

METHODS OF NON-OPERATIVE TREATMENT

REST

Since the days of H. O. Thomas (p. 3), who, more than a century ago, emphasised its value in diseases of the spine and limbs, rest has been one of the mainstays of orthopaedic treatment. Complete rest demands recumbency in bed – which, for the most part, is deprecated today – or immobilisation of the diseased part in plaster. But by ‘rest’ the modern orthopaedic surgeon does not usually mean complete inactivity or immobility. Often he means no more than ‘relative rest’, implying simply a reduction of accustomed activity and avoidance of strain. Indeed complete rest is enjoined much less often now than it was in the past, because diseases for which rest was previously important, such as poliomyelitis or tuberculosis, can now be prevented or are more readily amenable to specific remedies such as antibacterial agents. Complete rest after operations, formerly favoured, has given place in most cases to the earliest possible resumption of activity.

SUPPORT

Rest and support often go together; but there are occasions when support is needed but not rest – for example, to stabilise a joint rendered insecure by muscle paralysis, or to prevent the development of deformity. When support is to be temporary it can be provided by a cast or splint made from plaster of Paris or from one of the newer splinting materials. When it is to be prolonged or permanent an individually made surgical appliance, or orthosis, is required. Examples in common use are spinal braces, cervical collars, wrist supports, walking calipers, knee and ankle orthoses, and devices to control drop foot (Figs 11.3–Figs 11.5, pp. 177–8).

PHYSIOTHERAPY

Active intervention

Hydrotherapy

Hydrotherapy is a valuable way of allowing active pain-free movements of all joints in warm water. The warmth and buoyancy of the water relieve the muscle spasm and can help to reduce pain and increase the range of movement. Hydrotherapy is often particularly useful in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis.

Passive interventions

Ultrasound

Ultrasound waves at approximately 106 Hz can be projected as a beam from a transducer to induce a heating effect in deep tissues. They may also produce benefit from their mechanical and chemical effects on collagen and proteoglycans. Ultrasound is frequently used to reduce post-traumatic haematoma, oedema and adhesions of joints and their associated soft tissues.

LOCAL INJECTIONS

The indications for local injections fall into two groups:

DRUGS

Sedatives may be given if needed to promote sleep, but as with analgesics the rule should be to prescribe no more than is really necessary.

Anti-inflammatory drugs are those that damp down the excessive inflammatory response that may occur especially in rheumatoid arthritis and related disorders, by inhibiting the cyclo-oxygenase enzymes responsible for prostaglandin formation. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs are generally to be preferred – especially in the first instance – and they are a mainstay in the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Many of these drugs also have an analgesic action. The powerful steroids cortisone, prednisolone, and their analogues should be used with extreme caution and indeed should be avoided altogether whenever possible, because through their side effects they may sometimes do more harm than good. Nevertheless there are times when their use may be justified – as for instance in acute exacerbations of rheumatoid arthritis, and especially in polymyalgia rheumatica and giant-cell arteritis (see p. 166).

MANIPULATION

The subject will be considered under three general headings:

Manipulation for correction of deformity

In this category manipulation has its most obvious application in the reduction of fractures and dislocations. It is also used to overcome deformity from contracted or short soft tissues – as, for example, in congenital club foot. Yet another simple example is the forcible subcutaneous rupture and dispersal of a ganglion over the dorsum of the wrist.

Manipulation for relief of chronic pain

In this third category of case treatment by manipulation is somewhat empirical, because in many instances it is impossible to determine precisely the nature of the underlying pathology, and consequently the way in which manipulation acts is a matter of conjecture and – it must be said – of misconception.1 Manipulation is used in such cases simply because previous experience has proved that it is often successful.

The painful conditions that respond best to manipulation are chronic strains, especially of the tarsal joints, the joints of the spinal column, and the sacro-iliac joints. A chronic strain may be the consequence of an acute injury that has not been followed by complete resolution, or it may be caused by long-continued mechanical overstrain. It is generally surmised that adhesions are present that prevent the extremes of joint movement (even though a restriction of movement may not be obvious clinically), that these adhesions are painful when stretched, and that the effect of manipulation is to rupture them. An alternative explanation that is advanced in certain cases is that there is a minor displacement of the joint surfaces or of an intra-articular structure (even though this can seldom be demonstrated radiologically), and that the effect of manipulation is to restore normal apposition.

OPERATIVE TREATMENT

The chief essential of any operation is that it should not make the patient worse. This is so obvious that the statement may sound almost absurd. Yet it is unfortunately true that a disturbing number of operations carried out for orthopaedic conditions do in fact cause more harm than good for one reason or another. Hence the selection of cases for operation, the choice of the most appropriate operation in given circumstances, the technical performance of the operation, and the post-operative management are matters of the highest importance, and they call for a high degree of judgement and skill. Herein lies much of the fascination of orthopaedic surgery.

OSTEOTOMY

Osteotomy is the operation of cutting a bone or creating a surgical fracture.

Indications. The general indications for osteotomy are as follows:

Technique. If the bone is relatively soft (as in children) it may be divided simply with an osteotome or, in the case of a thin bone, by bone-cutting forceps. The strong cortex of the major long bones in an adult is not easily divided in that way because it tends to splinter; so most surgeons weaken the bone by making multiple drill holes before applying the osteotome, or, alternatively, they use a powered saw or a high-speed dental burr. When the bone has been divided and the necessary correction made it is often convenient to fix the fragments with a plate, nail-plate, or medullary nail: this may allow external splintage to be dispensed with. If internal fixation is not used the fragments may be immobilised by an external fixator; or they may be held in position by a suitable splint or plaster until union has occurred.

ARTHRODESIS

Indications. Arthrodesis is indicated mainly in the following conditions:

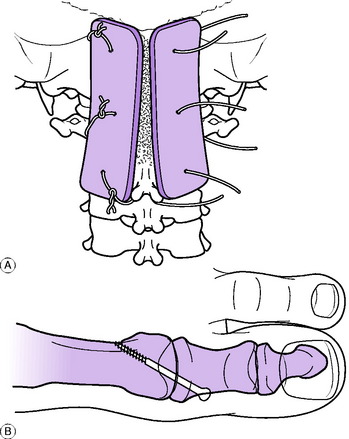

Examples of methods for arthrodesing the spine and a metatarso-phalangeal joint of the toe are illustrated in Fig. 4.1.

Position for arthrodesis. The best position for arthrodesis should not be regarded as rigidly established for each joint: variations may be appropriate and desirable in individual cases – for instance, to conform to the requirements of the patient’s work. The following is only a general guide. Shoulder: 30 ° of abduction and flexion, with 40 ° of medial rotation. Elbow: If only one elbow is affected, 75 ° of flexion from the fully extended position (or according to the requirements of the patient’s work). If both elbows are affected, one should be in flexion 10 ° above the right angle and the other about 20 ° below the right angle. If forearm rotation is lost the most useful position of the forearm is in 10 ° of pronation. Wrist: Extended 20 °. Metacarpo-phalangeal joints: Flexed 35 °. Interphalangeal joints: Semiflexed. Hip: About 15 ° of flexion; no abduction or adduction. Knee: About 20 ° of flexion. Ankle: In men, right angle; in women, 15–25 ° of plantarflexion, according to accustomed height of heel. Metatarso-phalangeal joint of big toe: Slight extension, depending upon the accustomed height of shoe heel.

ARTHROPLASTY

Indications. The indications for arthroplasty vary with the particular joint affected and the degree of disability. Broadly, it has a use in the following conditions:

Methods of arthroplasty

Each method has its merits, disadvantages and special applications.

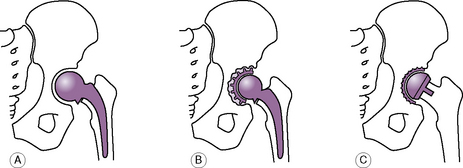

Excision arthroplasty. In this method one or both of the articular ends of the bones are simply excised, so that a gap is created between them (Fig. 4.2) effectively creating a false joint or pseudarthrosis. The gap fills with fibrous tissue, or a pad of muscle or other soft tissue may be sewn in between the bones. By virtue of its flexibility the interposed tissue allows a reasonable range of movement, but the joint often lacks stability making it less suitable for the large weight-bearing joints of the lower limb. Excision arthroplasty is used most commonly at the metatarso-phalangeal joint of the big toe, in the treatment of hallux valgus and hallux rigidus (Keller’s operation). It is also occasionally used at the hip, usually as a salvage operation after failed replacement arthroplasty. It is used occasionally at the elbow, the shoulder, and certain of the small joints of the hands and feet.

Hemi-arthroplasty (half-joint replacement arthroplasty). In a hemiarthroplasty only one of the articulating surfaces is removed and replaced by a prosthesis of similar shape (Fig. 4.3A). The prosthesis is usually made from metal. When appropriate, it may be fixed into the recipient bone with acrylic filling compound or ‘bone cement’. The opposing, normal articulating surface is left undisturbed. The technique has its main application at the hip, where prosthetic replacement of the head and neck of the femur is commonly practised for femoral neck fracture in the elderly. The disadvantage is that any degeneration in the unreplaced articular surface will accelerate with recurrence of pain and loss of movement making it unsuitable for younger patients. It has rather a limited use elsewhere, examples being the replacement of the head of the radius after certain types of fracture, and replacement of the lunate bone in Kienböck’s disease.

Total replacement arthroplasty. In this technique both of the opposed articulating surfaces are excised and replaced by prosthetic components (Fig. 4.3B). In the larger joints one of the components is usually of metal and the other of high-density polyethylene, and it is usual for both components to be held in place by acrylic ‘bone cement’. In small joints such as the metacarpo-phalangeal joints a flexible one-piece prosthesis made from silicone rubber may be used.

Another approach to preserve bone in younger patients, who might require later revision surgery, is to resurface rather than replace the joint. Attempts have been made to achieve this biologically with autogenous chondrocytes in the knee, or with artificial materials as in the double cup arthroplasty of the hip (Fig. 4.3C). The longer-term results from these new techniques remain uncertain and it should be noted that a conventional well-fitted replacement joint may give good service for as long as 15–20 years, especially in the case of the hip or knee.

BONE GRAFTING OPERATIONS

Indications. Bone grafts are used mainly in three types of case:

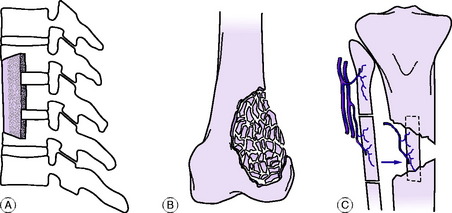

Strut grafts. A strut graft is usually obtained from strong cortical bone: the subcutaneous part of the tibia is a common site. The graft is fixed to the recipient bone either by internal fixation or by inlaying. Such a graft serves as an internal splint as well as providing a framework for the growth of new bone (Fig. 4.4A).

Strip grafts. Sliver or strip grafts are generally obtained from spongy cancellous bone – especially from the crest of the ilium. They are used commonly for ununited fractures. They are laid about the fracture, deep to the periosteum, and are held in place by suture of the soft tissues over them.

Chip grafts. These also are preferably obtained from cancellous bone. They serve the same purposes as sliver grafts but are smaller pieces of bone. The chips are packed firmly into, or around, the recipient bone and are held in place simply by suture of the soft tissues over them (Fig. 4.4B).

Vascularised grafts. These require a suitable donor site, such as the fibula, rib, or iliac crest, together with a meticulous microscopic technique to secure the necessary re-anastomosis of the nutrient vessels at the new site (Fig. 4.4C). The method is only suitable for use in specialised centres with the necessary equipment and expertise.

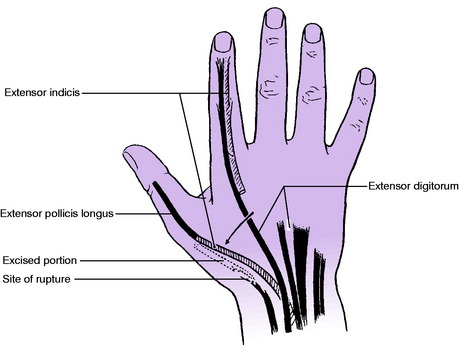

TENDON TRANSFER OPERATIONS

In the operation of tendon transfer, or tendon transplant, the insertion of a healthy functioning muscle is moved to a new site, so that the muscle henceforth has a different action. In this way the lost function of a paralysed or severed muscle can be taken over by one that is intact. In properly selected cases there need be no noticeable loss of power in the former sphere of action of the transferred muscle, because there is often considerable duplication or overlap in the function of individual muscles. Thus a tendon of flexor digitorum superficialis may be transferred to a new site without appreciably impairing the power of finger flexion, which can be adequately controlled by the flexor profundus. Similarly the extensor indicis can be spared for a new function without seriously interfering with the power of extension of the index finger (Fig. 4.5).

Indications. Tendon transfers have their main application in three groups of conditions:

Examples. 1. In a case of paralysis of the radial nerve, with loss of active extension of the wrist, fingers, and thumb, function may be restored by the following tendon transfers: pronator teres is transferred to extensor carpi radialis brevis; flexor carpi ulnaris is transferred to extensor digitorum and extensor pollicis longus; and palmaris longus is transferred to abductor pollicis longus. 2. In a case of congenital talipes equino-varus (p. 434) transfer of the tendon of the tibialis anterior or tibialis posterior to the outer side of the foot will help to prevent recurrence of the deformity. 3. In a case of rupture of the extensor pollicis longus, with extensive fraying of the tendon, direct repair may be impracticable. Function may be restored by transfer of the extensor indicis to the extensor pollicis longus (Fig. 4.5).

TENDON GRAFTING OPERATIONS

In tendon grafting a length of free tendon is used to bridge a gap between the severed ends of the recipient tendon.

Indications. The chief use of free tendon grafts is in the reconstruction of flexor tendons severed and adherent in the fibrous digital sheaths of the hand (p. 324).

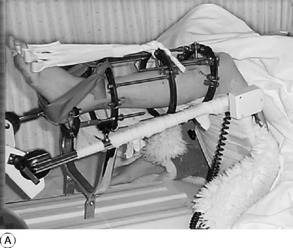

EQUALISATION OF LEG LENGTH

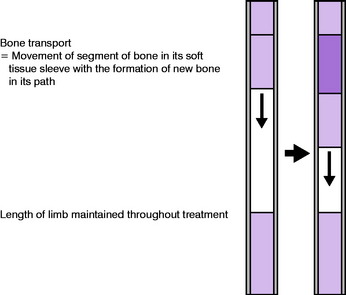

Leg lengthening is suitable mainly for children. It is achieved by dividing the appropriate bone (usually the tibia, sometimes the femur) and then gradually elongating the limb in a special screw-distraction apparatus at the rate of about 2 mm a day. A maximum of about 5 cm may be gained. The procedure is time-consuming and trying for the patient, and should be reserved for carefully selected cases in which the discrepancy in length is marked. A more recent innovation is the technique of bone transport, in which a length of the diaphysis is moved slowly downwards to fill a gap, while new bone forms to fill in the space created by its advancement (Fig. 4.6). These techniques have been facilitated by the introduction of the ring frame distraction apparatus of Ilizarov1, which allows correction of angulation as well as lengthening (Fig. 4.7).

Fig. 4.6 The mechanism of bone transport with new bone being formed in a healthy area by distraction.

Tissue distraction techniques

Relatively recently, the principle of tissue distraction was described by Ilizarov. This states that if a tissue is very gradually pulled apart it responds by creating new tissue. The principle was initially described for bone, where it was shown that if a bone was divided and following a delay period of 3–10 days, was pulled apart at approximately 1 mm/day, the body responded by creating a column of callus, which eventually would consolidate into healthy new bone.

This process is now used extensively in limb lengthening, bone transport and the correction of deformity. In the latter case, the bone is gradually straightened and rotated to the desired position. In bone transport, the same process is used to fill a bone defect (which may have arisen as a result of trauma or from the treatment of bone infection or tumours), the bone is divided through a healthy area and a segment of bone is pulled through the defect in order to create a column of new bone which fills the defect (Fig. 4.6).

AMPUTATION

With improvements in the design and manufacture of modern prosthetic limbs, the function after below-knee amputation is usually extremely good (Fig. 4.8). However after above-knee amputation, walking is more difficult and requires approximately a third more energy than normal. Function after upper limb amputation is also far less good, and upper limb amputation should be avoided if at all possible. As many as 80% of patients may experience ‘phantom limb’ sensation after amputation, that is they feel a limb that is no longer there and this may be accompanied by persistent pain.

1 Non-medical practitioners – especially chiropracters and osteopaths – often postulate ‘displacements’ (for instance, of vertebrae) which clearly do not exist.

1 Gauril Abramovich Ilizarov (1921–1992) Russian surgeon with little formal research training who developed practical application of tension stress to tissues. Became Professor at Kurgen Institute in Siberia and was elected to the Soviet Academy of Medicine.