6 General affections of the skeleton

A large number of general affections of the skeleton have been described. Even an incomplete description could occupy a large volume. Fortunately many of these affections are so rare that it is unnecessary for the student to concern himself with them. Most of the others require only brief consideration. Clearly, many of the affections to be described have a congenital basis and many of them cause deformity; so there is inevitably some overlap between this chapter and Chapter 5.

CLASSIFICATION

The following classification is based on that of Wynne-Davies and Fairbank (1976).

BONE DYSPLASIAS

ACHONDROPLASIA

Clinical features. Achondroplasia is apparent at birth, the child being strikingly dwarfed, with very short limbs that are out of proportion to the trunk: shortness is especially marked in the proximal segments of the limbs (Fig. 6.1). Adult achondroplasts are seldom more than 130 cm (4 feet 3 inches) in height. The hands are short and broad, the central three digits being divergent and of almost equal length (‘trident’ hand). The head is slightly larger than normal, with a bulging forehead and depressed nasal bridge. There is marked lumbar lordosis, often with thoracic kyphosis, which may occasionally lead to compression of the spinal cord. There is no mental impairment and life expectancy is usually normal.

OSTEOGENESIS IMPERFECTA (Fragilitas ossium)

Osteogenesis imperfecta is a congenital and inheritable disorder – or more probably a heterogeneous group of disorders – in which the bones are abnormally soft and brittle, on account of defective collagen formation. In addition to the bones, other collagen-containing tissues such as teeth, skin, tendons, and ligaments may be abnormal. It is usually transmitted as an autosomal dominant, but in a severe variant of the disease the parents are normal and a fresh gene mutation or autosomal recessive inheritance is postulated.

Clinical features. In the worst cases, which occur sporadically rather than from inheritance and probably represent a distinct entity, the child is born with multiple fractures and does not survive. In the less severe examples fractures occur after birth, often from trivial violence. As many as fifty or more may be sustained in the first few years of life. The fractures unite readily, but in the more severe cases marked deformity often develops, either from malunion or from bending of the soft bones (Fig. 6.2), and such patients may be badly crippled. In the milder cases there is a tendency for fractures to occur less frequently in later life.

MULTIPLE HEREDITARY EXOSTOSES (Diaphyseal aclasis)

Pathology. The fault is in the epiphysial cartilage plate. Nests of cartilage cells become displaced and give rise to bony outgrowths, which are capped by proliferating cartilage. Growth of the exostoses may cease at skeletal maturity. These exostoses, or osteochondromata, constitute one type of benign bone tumour (p. 109). The number of outgrowths varies; often there are between ten and twenty, of varying size. In severe cases the process of remodelling by which a bone attains its normal adult shape is impaired, and there may be marked deformity, with reduction of longitudinal growth and consequent shortness of stature. Malignant change in the cartilaginous cap of one of the tumours can lead to the development of a chondrosarcoma (the lifetime risk is approximately 5%).

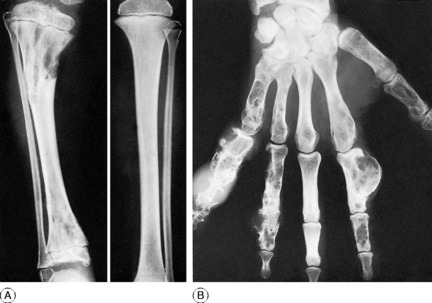

Radiographs show the bony outgrowths. In severe cases the bones are broad and ill modelled (Fig. 6.3).

MULTIPLE ENCHONDROMATOSIS (Dyschondroplasia; Ollier’s disease1)

In dyschondroplasia masses of unossified cartilage persist within the metaphyses of certain long bones, and the growth of the bone is retarded. The condition becomes evident in childhood, but the cause is unknown. In contrast with multiple hereditary exostoses, just described, heredity plays no part.

Any bone formed in cartilage may be affected. The more rapidly growing ends of the femur and tibia (that is, the ends near the knee) and the small long bones of the hands and feet are particularly common sites. There is a tendency for the disorder to affect one side of the body predominantly, or even exclusively. When a major long bone is affected interference with growth at the epiphysial cartilage adjacent to the lesion may lead to serious shortening and distortion of the bone (Fig. 6.4A). When skeletal growth ceases the masses of cartilage may ossify. Rarely one of the tumours undergoes malignant change, to become a chondrosarcoma (p. 117).

Clinical and radiographic features. A limb affected by dyschondroplasia is usually short and may be markedly deformed. The hands may be grotesquely enlarged by multiple cartilaginous swellings or outgrowths. Radiographs show multiple areas of transradiance in the affected bones (Fig. 6.4).

Treatment. Osteotomy may be required to correct deformities resulting from uneven growth of bone. If there is marked discrepancy in the length of the lower limbs a leg equalisation procedure (p. 46) may be advisable. Lesions in the hand may be curetted and packed with bone chips.

PAGET’S DISEASE1 (Osteitis deformans)

Clinical features. The affection seldom begins before the age of 40, but a childhood form is recognised. Often there are no symptoms, the condition being discovered incidentally during routine radiographic examination. When long bones are affected pain is sometimes complained of, but it is by no means an invariable feature. Bending of the softened long bones leads to deformity, usually in the form of anterior and lateral bowing of the femur or tibia (Fig. 6.5). Thickening may be obvious clinically, especially in the case of the tibia or the skull. Thus if the patient wears a hat he may notice that he requires progressively larger sizes. More importantly, bone thickening may also cause constriction of foramina in the skull, with risk of damage to a nerve – for instance the optic nerve or the auditory nerve.

Imaging. The main radiographic features (Figs 6.6 and 6.7) are:

The long bones are often shown to be bowed, the pelvis may be deformed, the vertebrae may be compressed and the vault of the skull thickened. Radioisotope scanning with 99mtechnetium shows markedly increased uptake in the affected bones.

Both drugs inhibit bone resorption. They reduce bone turnover, with lowering of plasma alkaline phosphatase, and both are effective in relieving bone pain in a high proportion of cases. Treatment must, however, be prolonged. Unlike calcitonin, which must be injected (though nasal spray and suppository forms are being tried), a bisphosphonate compound may be taken by mouth. Moreover its benefit often persists for up to six months after the drug has been discontinued; so it is the preferred drug in the first instance, on the basis of cost and ease of administration.

POLYOSTOTIC FIBROUS DYSPLASIA

Replacement of bone by fibrous tissue forms a conspicuous part of several unrelated bone diseases. In two conditions in particular, fibrous replacement is the predominant change. In one of these – parathyroid osteodystrophy – the changes are associated with hyperparathyroidism (p. 73). In the other, now to be described, there is fibrous replacement without any evidence of excessive parathyroid secretion.

Radiographs of the affected bones show well-defined transradiant areas which often have a characteristic homogeneous or ‘ground-glass’ appearance: these changes may be localised and patchy rather than uniform. The lesions are in the shaft and metaphyses rather than the epiphyses. When the lesion is extensive the cortex is expanded and thin, and the bone is bent when weight-bearing, producing deformities such as the ‘shepherd’s crook’ in the proximal femur (Fig. 6.8). Sometimes the lesion has a honeycombed appearance.

Investigations. There is no consistent biochemical abnormality of the blood. In a few cases the plasma alkaline phosphatase has been raised.

NEUROFIBROMATOSIS (von Recklinghausen’s disease1)

Complications. Occasionally a neurofibroma may undergo malignant change, to become a neurofibrosarcoma.

Treatment. A neurofibroma that is causing symptoms should be excised.

MYOSITIS OSSIFICANS PROGRESSIVA (Fibrodysplasia ossificans)

Pathology.1 The ectopic bone is formed by metaplasia of connective-tissue cells, not from displaced osteoblasts.

INBORN ERRORS OF METABOLISM

GAUCHER’S DISEASE

Gaucher’s disease is one of the group of lysosomal storage diseases included under the generic title mucopolysaccharidoses or sphingolipidoses. It is a rare lipoid storage disease of autosomal recessive inheritance, in which the enzyme beta-glucosidase is deficient and gluco-cerebroside accumulates in reticulo-endothelial cells of the spleen, liver, bone marrow, and other tissues.

Investigations. Bone marrow biopsy usually yields typical Gaucher cells.

HISTIOCYTOSIS X (Skeletal granulomatosis)

All occur mostly in children or young adults.

Eosinophilic granuloma

Radiologically the lesion is seen as a clear-cut hole in the bone – usually a rib, skull bone, vertebra, pelvic bone, femur, or humerus. An affected vertebral body may collapse, becoming compressed into a thin wafer (see Calvé’s vertebral compression, p. 235). Examination of the blood usually fails to show any abnormality.

Eosinophilic granuloma may simulate a bone cyst, a primary or metastatic bone tumour, or tuberculosis. If multiple, it resembles Hand–Schüller–Christian disease.

Hand–Schüller–Christian disease

Treatment. Radiotherapy may cause the lesions to regress, but the long-term prognosis is poor.

METABOLIC BONE DISEASE

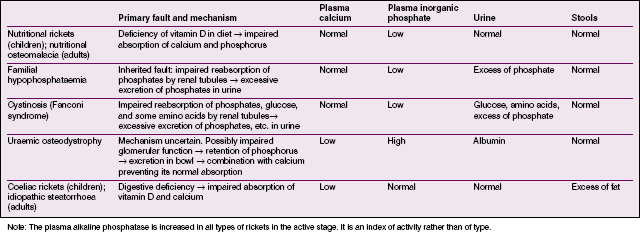

The majority of these disorders are associated with diffuse rarefaction of the skeleton and their causes are listed in Table 6.1.

| Cause | Diagnostic features |

|---|---|

| Osteoporosis | |

| Prolonged recumbency | History of confinement to bed for months or years |

| Idiopathic | Post-menopausal. Spine predominantly affected. No biochemical change in blood |

| Hyperparathyroidism | Diagnostic biochemical changes in blood: plasma calcium increased; plasma phosphate decreased |

| Glucocorticoid excess (Cushing’s syndrome) | Characteristic clinical features: obesity, hypertrichosis, hypertension, amenorrhoea in women |

| Osteomalacia | |

| Rickets (all types) | Rachitic changes at growing epiphyses. Biochemical changes depend on type of rickets (Table 6.2, p. 77) |

| Nutritional osteomalacia | Dietary deficiency apparent. Characteristic biochemical changes in blood: plasma calcium normal (or decreased); plasma phosphate decreased (Table 6.2, p. 77) |

| Idiopathic steatorrhoea | Excess of fat in faeces. Blood changes: plasma calcium decreased; plasma phosphate normal (Table 6.2, p. 77) |

| Tumour | |

| Multiple myeloma | Usually multiple circumscribed lesions, but may be diffuse. Bence Jones proteose often present in urine. Marrow biopsy shows excess of plasma cells |

| Diffuse carcinomatosis | Primary tumour demonstrable |

| Leukaemia | Blood examination and marrow biopsy show excess of immature white cells |

HYPERPARATHYROIDISM (Parathyroid osteodystrophy; generalised osteitis fibrosa cystica; von Recklinghausen’s disease)

Clinical features. The patient is adult. There are pains in the bones, indigestion, and weakness. There may also be deformity from bending of softened bone, or a pathological fracture.

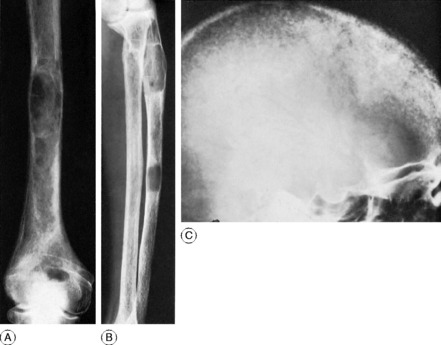

Radiographic features. Radiographs show rarefaction of the whole skeleton. The loss of density may be marked, and the cortices very thin. An early sign is irregular subperiosteal cortical erosion in the phalanges of the fingers. Scattered cystic changes may be present in the long bones (Fig. 6.9A, B). The skull shows a uniform fine granular mottling, sometimes with small translucent cyst-like areas (Fig. 6.9C). Radiographs of the renal tracts often show nephrolithiasis.

Diagnosis. This is from other causes of diffuse or generalised rarefaction of bone. These are summarised in Table 6.1.

Treatment. The causative parathyroid tumour should be located and removed.

NUTRITIONAL RICKETS

In rickets there is defective calcification of growing bone1 in consequence of a disturbed calcium–phosphate metabolism. With the general improvement in economic conditions infantile rickets has become rare in Western countries. There is, however, a relatively higher incidence among immigrants from the West Indies and from Asia.

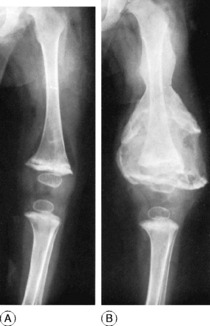

Pathology. Vitamin D promotes the absorption of calcium and phosphorus from the intestine. Its deficiency therefore leads to inadequate absorption of calcium and phosphorus. The level of calcium in the blood can then be maintained only at the expense of the skeletal calcium. Proliferating osteoid tissue in the growing epiphyses remains uncalcified, and there is a general softening of the bones already formed (Fig. 6.10).

Radiographic features. There is a general loss of density of the skeleton with thinning of the cortices. The most striking changes, however, are in the growing epiphyses. The vertical depth of the epiphysial lines is increased, the epiphyses are widened laterally, and the ends of the shafts are hollowed out or ‘cupped’ (Fig. 6.10). Bending of the bones may be obvious.

Diagnosis. If rickets is suspected an antero-posterior radiograph of a wrist should be obtained. The radiographic features are diagnostic of rickets, but biochemical examinations are required to indicate its type (Table 6.2, p. 77).

OTHER FORMS OF RICKETS

Familial hypophosphataemia (chronic phosphate diabetes; vitamin-resistant rickets)

Familial hypophosphataemia is a hereditary disorder transmitted by an X-linked dominant gene. The nature of the primary defect is uncertain: it may be a failure of normal reabsorption of phosphate by the renal tubules, or it may be a fault in the absorption of calcium from the intestine. Bone changes, which are like those of nutritional rickets, may become manifest soon after the first year of life. The characteristic biochemical features are: normal plasma calcium, low plasma phosphate level not corrected by vitamin D, increased alkaline phosphatase, and excess of phosphate in the urine (Table 6.2, p. 77). Relatives who are clinically unaffected may nevertheless show hypophosphataemia.

Treatment. Vitamin D in high doses should be combined with the administration of phosphates. Treatment on these lines corrects the bone changes but does not restore the plasma phosphate to a normal level. Improved results have been achieved by the use of a synthetic vitamin D analogue, 1α-hydroxyvitamin D3. Surgical correction of residual deformities may be required.

Cystinosis (Fanconi syndrome; renal tubular rickets with glycosuria and amino-aciduria)

In cystinosis (Fanconi syndrome) rachitic changes in the bones are associated with renal glycosuria and amino-aciduria. The primary defect, a congenital fault transmitted by a recessive mutant gene, is a failure of the proximal renal tubules to reabsorb phosphate, glucose, and certain amino acids in the normal way. The excessive loss of phosphates in the urine leads to depletion of the bone phosphate. Onset may be later in childhood than that of nutritional rickets, but the bone changes are the same. The characteristic biochemical features are: normal plasma calcium; low plasma phosphate; increased alkaline phosphatase; and excess of phosphate in the urine, which also contains glucose and certain amino acids (Table 6.2, p. 77).

Uraemic osteodystrophy (renal osteodystrophy; renal (glomerular) rickets; renal dwarfism)

Radiographs show epiphysial changes that are generally similar to those of nutritional rickets (Fig. 6.11).

Investigations. The biochemical changes are characteristic (Table 6.2). The plasma phosphate is markedly increased. The plasma calcium is low. The blood urea is raised, often to a high figure. Albumin is usually present in the urine.

Prognosis. Unless the renal lesion is remediable gradual progression is likely, with poor prognosis.

Coeliac (gluten-induced) rickets

Investigations. The biochemical changes in the blood differ from those of nutritional rickets. The plasma calcium is low. The plasma phosphate is normal or low (Table 6.2, p. 77). Diagnosis should be confirmed by jejunal biopsy effected by a swallowed capsule with a special cutting device.

Treatment. There is steady improvement in the calcification of the skeleton as the primary disorder is brought under control. The diet should be free from gluten and should contain an abundant supply of calcium and vitamin D.

NUTRITIONAL OSTEOMALACIA

Investigations. The plasma calcium is normal or low. Plasma phosphate is low. Alkaline phosphatase is increased. The calcium balance is negative (Table 6.2, p. 77). Serum levels of 25-hydroxyvitamin D are low.

Diagnosis. Nutritional osteomalacia must be distinguished from other causes of diffuse rarefaction of bone (Table 6.1, p. 74). In the elderly it may be mistaken for idiopathic osteoporosis.

VITAMIN C DEFICIENCY (Infantile scurvy)

Pathology. The most striking changes are in the long bones. There is a lack of osteoblastic activity in the epiphysial growth cartilage (growth plate). Haemorrhage, beginning at the epiphysial cartilage, extends beneath the periosteum, which may be raised from the bone throughout its whole length. Haemorrhages also occur from other sites, especially from the gums or within the orbit.

Radiographic features. Plain radiographs show a dense line at the junction between metaphysis and epiphysial cartilage, with a clear band of rarefaction on the diaphysial side (Fig. 6.12A). Later there is ossification in the subperiosteal haematoma, as a result of which the bone is often markedly thickened (Fig. 6.12B).

Investigations. Ascorbic acid is deficient in the plasma.

Treatment. The disease responds readily to the administration of vitamin C.

ENDOCRINE DISORDERS

OSTEOPOROSIS (Idiopathic osteoporosis; post-menopausal osteoporosis)

Pathology. The whole skeleton is affected, but the changes in the spine are more obvious than those elsewhere. The cortices of the vertebrae are thinner than normal, and the bone is rarefied throughout from thinning of the individual trabeculae and widening of the vascular canals. In other words there is a reduction of total bone mass. Compression fracture of one or more of the vertebral bodies is liable to occur from only trivial violence. Even without fracture the thoracic vertebrae tend gradually to become wedge-shaped so that the spine bends forward to produce a rounded kyphosis. The long bones – particularly the upper end of the femur and the lower end of the radius – are also prone to fracture easily.

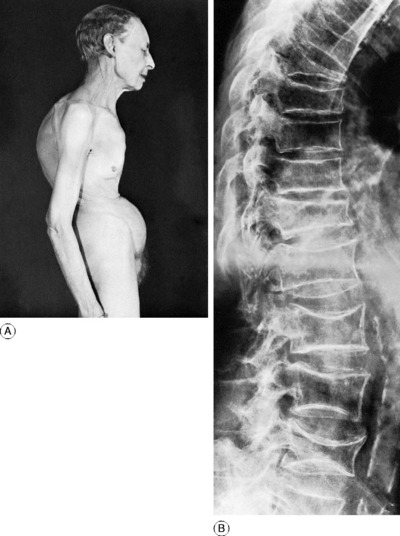

Clinical features. The patient is often a woman of over 60. The osteoporosis may be symptomless and may be found only by chance. In other cases there is pain in the back. The pain occurs in two forms – a mild generalised ache, and a sharper pain of sudden onset, denoting a compression fracture. Examination reveals a rounded kyphosis in the thoracic region. If a vertebral body has collapsed there may be a more angular kyphosis with prominence of a spinous process in the thoracic or thoraco-lumbar region. The trunk is shortened, with consequent loss of height, and there is a transverse furrow across the abdomen (Fig. 6.13A).

Radiographic features. The striking feature is the reduced density of the vertebral bodies, which become concave at their upper and lower surfaces from pressure of the intervertebral discs. Often there is wedging of one or more of the vertebral bodies from compression fracture (Fig. 6.13B). Other parts of the skeleton are also rarefied, but less obviously.

Diagnosis. Osteoporosis may be confused with other forms of diffuse rarefaction of bone, especially that caused by parathyroid osteodystrophy, glucocorticoid excess (Cushing’s syndrome), osteomalacia of various types, carcinomatosis, myelomatosis, or leukaemia (Table 6.1, p. 74). Diagnosis rests largely on the exclusion of these specific disorders.

HYPOPITUITARISM

Deficient secretion of the anterior lobe of the pituitary gland leads to various types of disturbance of skeletal growth, often with impairment of sexual development and sometimes with learning disabilities. The patient may be dwarfed, or on the other hand there may be good stature with marked obesity. The orthopaedic importance of this latter condition is that it may predispose to slipping of the upper femoral epiphyses in adolescents (p. 371) – as indeed may obesity from any cause.

ACROMEGALY

The primary fault is the same as in gigantism – namely, an excessive secretion of pituitary growth hormone – but it occurs after the epiphyses have fused. It is characterised by enlargement of the bones, especially of the hands, feet, skull, and mandible.

1 Louis Ollier (1830–1900) French surgeon who was senior surgeon at Lyons and described the clinical and radiological features of the condition in 1899. He was also an army surgeon and was decorated by the French President for his service.

1 Sir James Paget (1814–1899) English surgeon who worked at St Bartholomew’s Hospital, London and described the disease in great detail in 1877.

1 Frederich von Recklinghausen (1833–1910) Distinguished German pathologist working in Strasbourg who described this and several other diseases that bear his name.

1 This disease, formerly known as myositis ossificans progressiva, must not be confused with post-traumatic myositis ossificans. The two conditions are entirely distinct. Post-traumatic ‘myositis ossificans’ is misnamed: it is nothing more than ossification within a subperiosteal haematoma.

1 When similar influences act on mature adult bone the condition is known as osteomalacia.