Chapter 33 Treatment of Obesity and Eating Disorders

| Abbreviations | |

|---|---|

| CNS | Central nervous system |

| DA | Dopamine |

| GI | Gastrointestinal |

| 5-HT | Serotonin |

| MAO | Monoamine oxidase |

| NE | Norepinephrine |

Therapeutic Overview

| Therapeutic Overview |

|---|

| Obesity |

| Significant risk factors should be present before initiating drug therapy |

| Patients with concurrent diseases such as diabetes and hypertension require close monitoring |

| Exercise and a supervised dietary plan are essential |

| Centrally active drugs that enhance aminergic transmission may be of benefit |

| Peripherally active drugs that decrease fat absorption may be of benefit |

| Anorexia and Bulimia |

| Baseline medical and psychological assessment |

| Psychotherapy is cornerstone of treatment |

| Antidepressants may be of benefit |

| Cachexia |

| Associated with advanced cancers and AIDS |

| Corticosteroids, progestational agents, anabolic steroids, and stimulation of cannabinoid type 1 receptors stimulate appetite and weight gain |

Mechanisms of Action

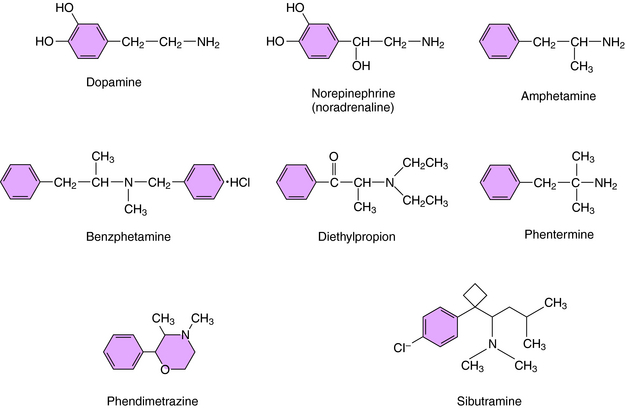

Drugs approved for the treatment of obesity include centrally active agents and the GI lipase inhibitor orlistat. The four sympathomimetics currently approved for the treatment of obesity include benzphetamine, diethylpropion, phentermine, and phendimetrazine. These drugs are β-phenethylamine derivatives structurally related to the biogenic amines norepinephrine (NE) and dopamine (DA) and to the stimulant amphetamine (Fig. 33-1). As a consequence of the latter, these agents have been deemed to have the potential for abuse and thus are classified by the U.S. DEA as Schedule III (benzphetamine and phendimetrazine) and Schedule IV (diethylpropion and phentermine) drugs, with diethylpropion and phentermine producing less central nervous system (CNS) stimulation than benzphetamine and phendimetrazine. All these agents are indicated for the short-term (up to 12 weeks) treatment of obesity and increase synaptic concentrations of NE or DA by promoting their release. These compounds are believed to suppress appetite through effects on the satiety center in the hypothalamus rather than effects on metabolism.

Orlistat is the only weight-loss drug that does not suppress appetite. Rather, orlistat binds to and inhibits the enzyme lipase in the lumen of the stomach and small intestine, thereby decreasing the production of absorbable monoglycerides and free fatty acids from triglycerides. Orlistat is a synthetic derivative of lipstatin, a naturally occurring lipase inhibitor produced by Streptomyces toxytricini. Normal GI lipases are essential for the dietary absorption of long-chain triglycerides and facilitate gastric emptying and secretion of pancreatic and biliary substances. Because the body has limited ability to synthesize fat from carbohydrates and proteins, most accumulated body fat in humans comes from dietary intake. Orlistat reduces fat absorption up to 30% in individuals whose diets contain a significant fat component. Reduced fat absorption translates into significant calorie reduction and weight loss in obese individuals. In addition, the lower luminal free fatty acid concentrations also reduce cholesterol absorption, thereby improving lipid profiles. Orlistat is not a controlled substance, is approved for the long-term treatment of obesity, and is now available over the counter.

Drugs for Anorexia and Bulimia

Based on evidence that individuals with anorexia and bulimia are prone to mood disturbances, the pharmacological treatment of these disorders has focused on use of antidepressants. Evidence supports the efficacy of these compounds for treatment of bulimia. Antidepressants in all classes including the tricyclic antidepressants, monoamine oxidase (MAO) inhibitors, and selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors have been shown to be equally efficacious. However, because of side effects associated with the use of tricyclic antidepressants and MAO inhibitors (Chapter 30), selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors may be considered first-line agents. Antidepressants reduce binge eating, vomiting, and depression and improve eating habits in bulimia but do not affect poor body image. Imipramine, desipramine, phenelzine, amitriptyline, and trazodone have all been used with some success, but currently fluoxetine is the only approved antidepressant for the treatment of bulimia. It is unclear whether the effectiveness of these compounds is due primarily to their antidepressant action or whether they are directly orexigenic (appetite stimulating). These compounds are ineffective for binge-eating disorder. Their mechanisms of action are discussed in Chapter 30.

Similar to the goal for therapy with anorectic and bulimic patients is the need to stimulate appetite in individuals with cachexia. In concert with nutritional counseling, progestational agents such as megestrol acetate, corticosteroids such as dexamethasone, and anabolic steroids such as oxandrolone and nandrolone have been shown to stimulate appetite and cause weight gain in these patients. The mechanisms of action of these compounds are discussed in Chapters 39, 40 and Chapters 41.

Pharmacokinetics

All centrally acting anorectic drugs are well absorbed from the GI tract and reach peak plasma levels within two hours. However, they differ somewhat in their pharmacokinetic profiles (Table 33-1).

| Drug | t1/2 (hrs) | Metabolism and Elimination |

|---|---|---|

| Benzphetamine | – | M, R |

| Diethylpropion | 4-8 for metabolites | M, R |

| Phendimetrazine | 1.9 for immediate-release preparation | M, R |

| 10 for sustained-released preparation | ||

| Phentermine | 19-24 | R |

| Sibutramine | 14-18 for metabolites | M, R |

M, Metabolized; R, renal.

Dronabinol is nearly completely absorbed after oral administration. It undergoes extensive first-pass hepatic metabolism, has high lipid solubility with a large (10 L/kg) apparent volume of distribution, and is 97% bound to plasma proteins. Hepatic metabolism yields both active and inactive metabolites, with 11-OH-delta-9-THC representing the primary active metabolite, which reaches plasma levels equal to that of the parent compound. Dronabinol and its metabolites are excreted in both urine and feces, with biliary excretion representing the primary route. Dronabinol has a terminal half-life of 25 to 36 hours.

The pharmacokinetics of the antidepressants are discussed in Chapter 30; those of the corticosteroids are discussed in Chapter 39, those of the progestational agents in Chapter 40, and those of the anabolic steroids in Chapter 41.

Relationship of Mechanisms of Action to Clinical Response

Pharmacovigilance: Side-Effects, Clinical Problems, and Toxicity

These drugs should be used as monotherapy and are contraindicated in patients receiving sympathomimetic amines, tricyclic antidepressants, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or MAO inhibitors because of documented cases of hypertensive crises. In addition, for compounds such as sibutramine that affect 5-HT, a 5-HT syndrome can be precipitated (see Chapter 30). A minimum drug-free period of 14 days is required for anyone using MAO inhibitors before therapy is initiated with these agents.

Orlistat is unique for treatment of obesity, as it does not carry a risk of cardiovascular side effects. Because its actions involve the GI system, its adverse effects are limited to this area. The most commonly reported GI complaints, which occur in as many as 80% of individuals, are most pronounced in the first 1 to 2 months and decline with continued use. Malabsorption of fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) and β-carotene occur, but no notable changes in the pharmacokinetic profiles of other drugs

have been reported. Long-term use of orlistat has not resulted in any documented cases of serious reactions.

Side effects associated with use of the anti-obesity drugs are listed in the Clinical Problems Box.