Chapter 62 Treatment of Meniscus Tears with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Reconstruction

Introduction

The incidence of lateral meniscus tears has been reported to be higher than the incidence of medial meniscus tears with acute ACL injuries.1 Shelbourne and Gray2 found that of 448 patients with acute ACL injuries, 62% had lateral meniscus tears and 42% had medial meniscus tears, whereas in 609 patients with chronic ACL deficiency, 49% had lateral meniscus tears and 60% had medial meniscus tears. Cipolla et al3 found that of 218 acute injuries, 59% had lateral meniscus tears and 28.5% had medial meniscus tears, whereas in 552 chronic ACL injuries, 41.6% had lateral meniscus tears and 74% had medial meniscus tears. The lateral meniscus is mobile and translates 9 to 11 mm in the anteroposterior plane, whereas the medial meniscus translates only 2 to 5 mm.4 The lateral meniscus is more frequently injured acutely because of its extreme mobility, and the peripheral and posterior portions of the meniscus are prone to getting caught in the joint during an ACL instability episode, which may explain the high incidence of posterior horn avulsion tears with acute ACL injuries. The less mobile medial meniscus is less injured with acute ACL injuries, and it may take consecutive giving-way episodes for the peripheral posterior third of the meniscus to become caught in the joint. When patients do have a medial meniscus tear with an acute ACL injury, it is typically a peripheral vertical tear in the posterior third of the meniscus. This tear can extend anteriorly with additional giving-way episodes and eventually become a bucket-handle tear.

Meniscus Tears to Leave in Situ

With acute ACL injuries, most meniscus tears are not symptomatic for the patient. The patient’s inability to fully extend the knee is usually due to the ACL stump being lodged in the intercondylar notch. Shelbourne et al5 found that joint line tenderness observed at the time of acute ACL injury does not correlate to the presence or absence of meniscus tears at the time of surgery. Over a 2-year period, 173 patients were seen for acute injury and were evaluated for joint line tenderness, and then the type of meniscus tear was recorded at the time of surgery. The investigators found that medial joint line tenderness was 45% sensitive and 34% specific for a medial meniscus tear. Lateral joint line tenderness was 58% sensitive and 49% specific for a lateral meniscus tear.5 We now delay ACL surgery until the patient’s knee has full range of motion and no swelling and the patient has good leg control. On the day of surgery, very few patients have joint line tenderness but about 50% have a meniscus tear.6 It appears that meniscus injuries in conjunction with acute ACL injuries are difficult to determine preoperatively based on joint line tenderness exam.

The meniscus has a blood supply provided by the perimeniscal capillary plexus, and these capillaries extend into 20% to 30% of the body of the medial meniscus and 10% to 25% of the lateral meniscus.7,8 Tears in the peripheral vascular zone of the meniscus are thought to be ideal for meniscus repair, but many can heal without specific repair treatment. The acuteness or chronicity of the ACL injury is not the deciding factor for determining the treatment of the meniscus. Rather, it is the location of the tear and the degenerative nature of the tear that help determine treatment.

Lateral Meniscus Tears

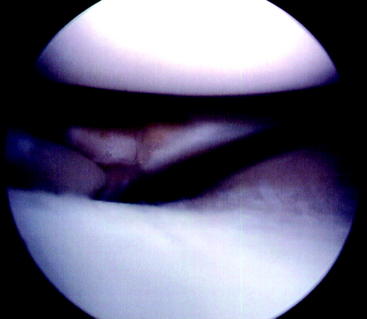

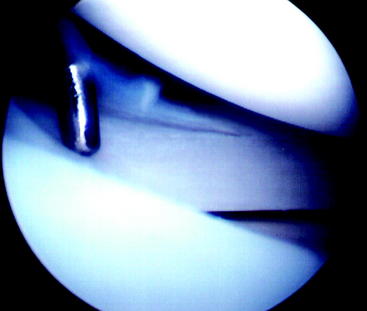

Complete removal of a torn lateral meniscus has a poor prognosis.9 In the early 1980s, the senior author observed the almost 100% success with repair of lateral meniscus tears and came to the conclusion that many of the lateral meniscus tears being repaired probably did not need repair. Therefore the senior author began to change his treatment of lateral meniscus tears from repairing 80% of the tears in 1984 to repairing 15% in 1992. During that same time, he changed his treatment from leaving lateral meniscus tears in situ in 4% of tears in 1984 to 70% in 1992. The types of lateral meniscus tears left alone included posterior horn avulsions (52 tears; Fig. 62-1), stable vertical tears that were posterior to the popliteus tendon (99 tears; Fig. 62-2), and nondisplaced vertical tears that extended anterior to the popliteus tendon (27 tears).10 With a follow-up at a mean of 2.6 years (range 1–9 years), Fitzgibbons and Shelbourne10 found that no patients returned to the clinic reporting symptoms of a lateral meniscus tear. One patient twisted his knee playing basketball at 114 days after ACL reconstruction and had a displaced bucket-handle medial meniscus tear. At the time of follow-up arthroscopy, the original vertical lateral meniscus tear had progressed to a complex T-type tear, but the tear did not extend anterior to the popliteus.

Shelbourne and Heinrich11 performed another long-term follow-up of 332 patients who had lateral meniscus tears left in situ or treated with abrasion and trephination without suture repair. The patients also had no medial meniscus tears or chondromalacia greater than grade II to isolate the factor of lateral meniscus tears in the long-term follow-up analysis. At a mean of 5.1 years after surgery, 162 patients (95%) had normal radiographs, six patients had nearly normal radiographs, and two patients had abnormal radiographs for lateral joint space narrowing using IKDC criteria. Of 70 patients with posterior horn avulsion tears left in situ, two (2.9%) underwent a subsequent procedure to remove the tear. Of 50 patients with radial flap tears, three patients (6%) needed a subsequent surgery for the tear. Of 169 patients with peripheral or posterior tears left in situ, three patients (1.8%) required subsequent surgery for the tear. None of the 43 patients who had peripheral or posterior tears treated with abrasion and trephination required further surgery.11

Medial Meniscus Tears

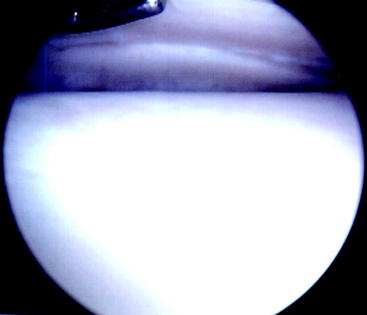

Medial meniscus tears seen at the time of acute ACL reconstruction are traumatic in nature and are usually in the vascular zone of the meniscus. A common type of tear seen with acute ACL injury is a peripheral or posterior stable medial meniscus tear, which can be easily missed (Fig. 62-3). This type of tear is not symptomatic for the patient, and it is possible that many of these tears heal on their own in patients who do not undergo an ACL reconstruction acutely or semi-acutely.

Shelbourne and Rask12 performed a follow-up study to determine the outcome of nondegenerative peripheral vertical medial meniscus tears that were stable and were treated either by leaving the tear in situ or with abrasion and trephination without suture repair. All the tears were greater than 1 cm long but could not be displaced into the intercondylar notch. Between 1982 and 1988, 139 tears were treated by leaving the tears in situ. Between 1989 and 1997, the tears were treated with abrasion and trephination. At a mean of 4.8 years after surgery, the number of patients who underwent subsequent arthroscopy for symptoms of a meniscus tear was 15 (10.8%) for the tears left in situ and 14 (6%) for the tears treated with abrasion and trephination. The mean time after ACL reconstruction that patients experienced symptoms was 2.5 years for the tears left in situ and 2.3 years for the tears treated with abrasion and trephination. As part of the same study, 176 patients had the same type of meniscus tear, but it was unstable and required suture repair. The failure rate of the repaired group was 13.6%.12

Trephination has been shown in both animal and clinical studies to enhance meniscal healing by creating vascular channels.13–15 Fox et al16 treated 26 incomplete peripheral vertical meniscus tears by trephination alone and had 90% clinical success, but all of the tears were less than 1 cm long. Weiss et al17 showed that medial meniscus tears of 1 cm or less can heal if left alone, but the study did not evaluate tears greater than 1 cm long.

It is accepted that peripheral vertical medial meniscus tears less than 1 cm long that are found at the time of ACL reconstruction can be left in situ or treated with trephination. Shelbourne and Rask12 have now shown that tears longer than 1 cm long can also be left in situ or treated with trephination and still have a very low rate of causing subsequent symptoms of a meniscus tear. Trephination is a simple technique to provide vascular channels in the meniscus for healing, and it avoids the risks associated with meniscus repair using sutures.

Meniscus Tears to Repair

McCarty et al18 published an extensive review of the different types of meniscus repair techniques and their results. It appears that most techniques can be successful, with rates ranging from 73% to 99% for clinical success and 25% to 90% for success of meniscal healing. The factors for success were similar for the different types of repairs: success was dependent on meniscus tear type, size, and location. To determine the success of meniscus repair, it would be most helpful for investigators to study specific types of meniscus tears instead of combining all types together.

Cannon and Vittori13 evaluated meniscal healing in 90 repairs done in conjunction with ACL reconstruction and 27 repairs in ACL intact knees, and the healing was related to rim width (vascular versus avascular zones), tear length (stable versus unstable), and joint compartment (lateral versus medial). Rim widths up to 2 mm had a healing success rate of 96%. Rim widths of 2 to 4 mm had a healing success rate of 84%, and rim widths of 4 to 5 mm had a success rate of 50%. Tear length less than 2 cm had a 94% success rate, and tear lengths of 2 to 4 cm had an 86% success rate. When the tear length was more than 4 cm, the healing rate was only 50%. Lateral meniscus tears successfully healed 93% of the time, whereas medial meniscus tears healed 73% of the time. Meniscus repair done with ACL reconstruction was more successful (93%) than repairs done in ACL intact knees (50% success), but there was no information provided as to the differences in rim width, tear length, or joint compartment between the two groups.13

Asahina et al19 also evaluated the factors that affected healing of meniscal repair of unstable, full-thickness, vertical, longitudinal tears longer than 15 mm in 98 patients evaluated by second-look arthroscopy. Of the 98 repairs, 73 completely healed, 13 incompletely healed, and 12 did not heal. Healing was achieved in 78% of medial meniscus repairs and 63% of lateral meniscus repairs. Repairs in the peripheral third zone had a statistically significant better healing rate of 87%, compared with 59% for repairs in the central third zone. The statistically significant factors in healing were rim width and meniscal locking. Meniscus tears in the central third zone that had been locked in the knee or could be locked at the time of surgery had a negative correlation to healing.19

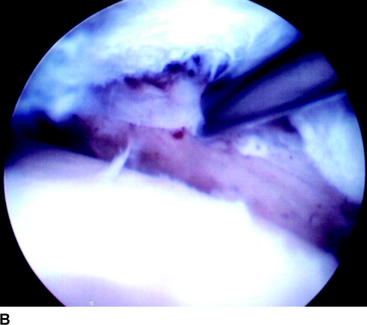

Unstable meniscus tears, such as bucket-handle tears, are common with chronic ACL instability (Fig. 62-4). Most bucket-handle meniscus tears are degenerative, which is why they are very seldom seen with acute ACL injuries. It is possible for a bucket-handle tear to be nondegenerative in a patient with chronic ACL laxity if he or she has been able to protect the knee from instability episodes and has just suffered a recent giving-way episode prior to the evaluation. In a series of 55 bucket-handle meniscus tears seen with chronic ACL deficiency, 43 tears (78%) were in the white-white nonvascular zone of the meniscus, 11 were in the red-white vascular zone, and one was in the red-red vascular zone.20

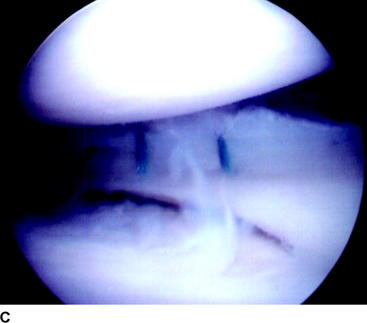

O’Shea and Shelbourne20 evaluated meniscal healing of repairs done on bucket-handle meniscus tears that were unstable and locked in the intercondylar notch in patients with chronic ACL deficiency. Patients underwent meniscus repair followed by rehabilitation to regain full knee range of motion, strength, and function before undergoing an ACL reconstruction at a later date. The menisci were evaluated with arthroscopy at the time of the ACL reconstruction, which occurred at a mean of 77 days after meniscus repair. Of 43 repairs done in the avascular zone of the meniscus, only five menisci showed no healing at the repair site. Of 11 repairs done in the red-white vascular zone of the meniscus, only one repair showed no healing. The one repair done in the red-red zone of the meniscus healed completely. At a subsequent follow-up at a mean of 4.3 years after repair, four patients had a failed repair that required subsequent arthroscopies to remove repairs done in the avascular zone of the meniscus (Fig. 62-5).

Rubman et al21 found similar success rates of meniscal repair in 198 meniscus tears that had a rim width of 4 mm or more. Most of the tears were either single (N = 92) or double (N = 40) longitudinal tears. Clinical success, defined as the patient being asymptomatic for tibiofemoral joint symptoms, was found in 80%. Arthroscopic follow-up evaluation of 91 of the tears found that 23 (25%) had completely healed, 35 (38%) had partially healed, and 33 (36%) failed. The authors concluded that repairs of the meniscus in the avascular zone is preferred over partial meniscectomy, especially in young athletic patients or patients with varus or valgus lower extremity malalignment. Noyes and Barber-Westin22 in a similar study found that 26 of 33 repairs of tears in the avascular zone remained asymptomatic at a mean of 33 months postoperatively for patients 40 years or older.

Thus it appears that meniscus tears, even in the avascular zone of the meniscus, can heal or remain asymptomatic with repair. The question remains as to whether repaired menisci, especially large bucket-handle tears in the avascular zone, function well enough to protect the joint and not cause symptoms for the patient in the long term. Shelbourne and Carr23 compared the results of meniscus repair versus partial meniscectomy of bucket-handle medial meniscus tears in ACL reconstructed knees. The patients had no other intraarticular pathology such as lateral meniscus tears or articular cartilage damage greater than Outerbridge grade 2. One would expect that patients who underwent meniscus repair would have better results than patients who had a partial meniscectomy. The mean modified Noyes subjective score was identical for the two groups, 90.9 points, at 8 years after surgery. Of note, however, was that when the repair group was analyzed based on whether the bucket-handle tear was degenerative or nondegenerative, patients who had a degenerative meniscus tear had a mean score of 87.1 points, which was statistically significantly lower than the mean of 93.9 points for patients who had a nondegenerative meniscus tear. Radiographic evaluation showed that 11 of 12 patients (92%) in the nondegenerative group had normal radiographs at follow-up versus only nine of 12 patients (75%) in the degenerative group. Interestingly, 41 of 52 patients (79%) who had partial meniscectomy of the bucket-handle tear also had normal radiographs. Therefore the authors concluded that repaired degenerative bucket-handle medial meniscus tears may not function normally in the knee to provide any advantage over partial meniscectomy.23

In a similar study, Shelbourne and Dersam24 compared the results of partial meniscectomy versus repair for bucket-handle lateral meniscus tears with ACL reconstruction. The patients had no other intraarticular pathology, such as medial meniscus tears or articular cartilage damage greater than Outerbridge grade 2. The mean time of subjective follow-up was 7 years for the repair group and 11 years for the removal group. The mean total subjective score for 57 patients in the repair group was 92.5 points, and the mean total score for the removal group was 88.7 points, which was not statistically significantly different. Patients in the removal group did have statistically significantly lower pain subscores on the subjective survey than patients in the repair group. Radiographic evaluation using IKDC criteria found that 83% of the removal group (8 years postoperatively) and 87% of the repair group (6 years postoperatively) had normal radiographs. The longer follow-up time for the removal group should have accentuated any detriment of meniscus removal of the tears versus meniscus repair. Although the subjective scores between groups were not statistically significantly different, we believe the P value of 0.2014 indicates a trend toward lower scores in the removal group.24

Timing of Meniscus Repair with Anterior Cruciate Ligament Surgery

There is one situation in which meniscus repair should not be performed at the same time as ACL reconstruction. Patients who have chronic ACL deficiency commonly seek treatment when they suffer a meniscus tear that is causing clicking, locking, or pain in the knee. Sometimes the common bucket-handle tear seen with chronic ACL instability will become locked in the intercondylar notch. When patients seek treatment, they want treatment for the immediate problem of the meniscus tear and may not be prepared mentally or socially to undergo an ACL reconstruction. Furthermore, there is a higher risk of arthrofibrosis when the patient undergoes ACL reconstruction when the knee does not have full range of motion equal to the opposite normal knee.25

Shelbourne and Johnson26 found a higher incidence of arthrofibrosis in patients who underwent meniscus repair or removal of a locked bucket-handle meniscus tear in conjunction with ACL reconstruction versus patients who underwent staged procedures of meniscus repair or removal, rehabilitation to restore normal knee motion, and ACL reconstruction at a later date. Four of 16 patients who underwent meniscus treatment and ACL reconstruction suffered arthrofibrosis, compared with 0 of 16 patients who underwent staged procedures. All of the patients had flexion contractures of 5 to 20 degrees with the locked bucket-handle meniscus tear, and the mean time that the meniscus was locked in the knee before surgery could be performed was 12.4 days.

Loss of knee extension is a common complication after ACL reconstruction. It is more commonly associated with ACL reconstruction after acute injury versus chronic instability, but any loss of normal knee extension to include normal hyperextension affects the long-term results after surgery. In a 10- to 20-year follow-up study of ACL reconstruction, any loss of normal knee extension or flexion after surgery was the most important factor related to lower subjective scores. Another significant factor considered in the regression analysis was partial medial or lateral meniscectomy, but any loss of knee motion was more important.27

All other types of meniscus repair can be done effectively in conjunction with ACL reconstruction. It is important that physicians not limit the ACL rehabilitation when a meniscus repair is done at the same time. Exercises to achieve full, symmetrical knee range of motion should begin on the day of surgery, and there is no reason to limit weight bearing. In the study by Shelbourne and Johnson26 in which patients underwent staged procedures for treatment of a locked bucket-handle meniscus tear followed by ACL reconstruction, 14 patients underwent meniscus repair. The rehabilitation allowed unrestricted weight bearing and full knee range of motion, and patients underwent ACL reconstruction at a later date when rehabilitation goals had been achieved. At the time of ACL reconstruction, an arthroscopy was performed to evaluate meniscal healing. The average time of evaluation was 72 days, and all repaired menisci had evidence of healing. Only one patient subsequently had a tear to the repaired meniscus at 18 months after repair. We believe that weight bearing with the knee in full extension pushes the meniscus toward the capsule and may promote healing.26

1 Bellabara C, Bush-Joseph CA, Bach BRJr. Patterns of meniscal injury in the anterior cruciate-deficient knee: a review of the literature. Am J Orthop. 1997;26:18-23.

2 Shelbourne KD, Gray T. Anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction with autogenous patellar tendon graft followed by accelerated rehabilitation: a two- to nine-year followup. Am J Sports Med. 1997;25:786-795.

3 Cipolla M, Scala A, Gianni E, et al. Different patterns of meniscal tears in acute anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) ruptures and in chronic ACL-deficient knees. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 1995;3:130-134.

4 Maitra RS, Miller MD, Johnson DL. Meniscal reconstruction. Part I. Indications, techniques, and graft considerations. Am J Orthop. 1999;28:213-218.

5 Shelbourne KD, Martini JD, McCarroll JR, et al. Correlation of joint line tenderness and meniscal lesions in patients with acute anterior cruciate ligament tears. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:166-169.

6 Shelbourne KD. 2006. Unpublished data

7 Arnoczky SP, Warren RF. Microvasculature of the human meniscus. Am J Sports Med. 1982;10:90-95.

8 Arnoczky SP, Warren RF. The microvasculature of the meniscus and its response to injury: an experimental study in the dog. Am J Sports Med. 1983;11:131-141.

9 Yocum LA, Kerlan RK, Jobe FW, et al. Isolated lateral meniscectomy. A study of twenty-six patients with isolated tears. J Bone Joint Surg. 1979;61A:338-342.

10 Fitzgibbons RE, Shelbourne KD. “Aggressive” nontreatment of lateral meniscal tears seen during anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:156-159.

11 Shelbourne KD, Heinrich J. The long-term evaluation of lateral meniscus tears left in situ at the time of anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:346-351.

12 Shelbourne KD, Rask BP. The sequelae of salvaged nondegenerative peripheral vertical medial meniscus tears with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthroscopy. 2001;17:270-274.

13 Cannon WDJr, Vittori M. The incidence of healing in arthroscopic meniscal repairs in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees versus stable knees. Am J Sports Med. 1992;20:176-181.

14 Zhang Z, Arnold JA, Williams T, et al. Repairs by trephination and suturing of longitudinal injuries in the avascular area of the meniscus in goats. Am J Sports Med. 1995;23:35-41.

15 Zhang ZN, Kaiyuan T, Yinkan X, et al. Treatment of longitudinal injuries in avascular area of meniscus in dogs by trephination. Arthroscopy. 1988;4:151-159.

16 Fox JM, Rintz KG, Ferkel RD. Trephination of incomplete meniscal tears. Arthroscopy. 1993;9:451-455.

17 Weiss CB, Lundberg ML, Hamberg P, et al. Non-operative treatment of meniscal tears. J Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71A:811-822.

18 McCarty EC, Marx RG, DeHaven KE. Meniscus repair: considerations in treatment and update of clinical results. Clin Orthop. 2002;402:122-134.

19 Asahina S, Muneta T, Yamamoto H. Arthroscopic meniscal repair in conjunction with anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: factors affecting the healing rate. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:541-545.

20 O’Shea JJ, Shelbourne KD. Repair of locked bucket-handle meniscal tears in knees with chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:216-220.

21 Rubman MH, Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Arthroscopic repair of meniscal tears that extend into the avascular zone: a review of 198 single and complex tears. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:87-95.

22 Noyes FR, Barber-Westin SD. Arthroscopic repair of meniscus tears extending into the avascular zone with or without anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction in patients 40 years of age and older. Arthroscopy. 2000;16:822-829.

23 Shelbourne KD, Carr DR. Meniscal repair compared with meniscectomy for bucket-handle medial meniscal tears in anterior cruciate ligament-reconstructed knees. Am J Sports Med. 2003;31:718-723.

24 Shelbourne KD, Dersam MD. Comparison of partial meniscectomy versus meniscus repair for bucket-handle lateral meniscus tears in anterior cruciate ligament reconstructed knees. Arthroscopy. 2004;20:581-585.

25 Shelbourne KD, Wilckens JH, Mollabashy A, et al. Arthrofibrosis in acute anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction: the effect of timing of reconstruction and rehabilitation. Am J Sports Med. 1991;19:332-336.

26 Shelbourne KD, Johnson GE. Locked bucket-handle meniscal tears in knees with chronic anterior cruciate ligament deficiency. Am J Sports Med. 1993;21:779-782.