CHAPTER 42 TREATMENT OF ESOPHAGEAL INJURY

The treatment of esophageal perforations remains controversial, with uncertainty surrounding several aspects of surgical management: the preferred method of surgical repair, the management of injuries recognized late, and the role of cervical esophagostomy for diversion, among others. Much of this controversy stems from the uncommon nature of these injuries. The relative infrequency of esophageal injury may be attributed to the deep location of this collapsed structure that is surrounded by vital organs. Many penetrating wounds injure the heart or aorta and result in death at the scene. Blunt injuries to the esophagus are very unusual. Anatomic features, with the lack of serosa, contribute to the difficulty in treatment. Given the frequency of delay in diagnosis and the complexity of operative treatment, injuries of the esophagus remain among the most difficult injuries to manage without major morbidity or mortality. Even the busiest trauma centers often encounter fewer than five esophageal injuries per year.

INCIDENCE

The incidence of esophageal injuries is low with most resulting from penetrating trauma. Esophageal trauma received little notice until the completion of World War II, with only 18 esophageal injuries recorded in the military records reviewed from that war and the Korean and Vietnam Wars combined. Numerous reports in the literature document the incidence of esophageal trauma to be less than 1% with the most common cause being penetrating injuries sustained from stab and gunshot wounds. The cervical esophagus represents the most common site of injury followed by thoracic and abdominal esophageal injuries. While these wounds occur relatively infrequently, they continue to be associated with high mortality ranging from 20% to 30%. Virtually all patients who sustain an esophageal injury also incur associated injuries to other respiratory, gastrointestinal, and vascular injuries. As a result, surgeons must maintain a high index of suspicion so that untoward diagnostic delays may be avoided.

SURGICAL TREATMENT

Most injuries of the esophagus can be primarily repaired if promptly diagnosed. Small injuries may be closed transversely, whereas injuries larger than 2–3 cm can be closed longitudinally in order to avoid undue tension. Unfortunately, diagnostic delay often creates a situation associated with significant mediastinal inflammation and sepsis. Furthermore, the lack of a serosal layer complicates primary reapproximation as the esophageal tissues are extremely friable especially under these circumstances. Numerous strategies have been proposed including non-operative management with drainage, esophageal resection, and diversion with exclusion. The use of pleural and pericardial flaps has been widely described for buttressing primary repairs. More recently, various muscle flaps have been advocated for primary repair of esophageal defects. However, adequate esophageal tissue debridement, tension-free repairs, and effective drainage remain the mainstays of successful operative management.

THORACIC ESOPHAGUS

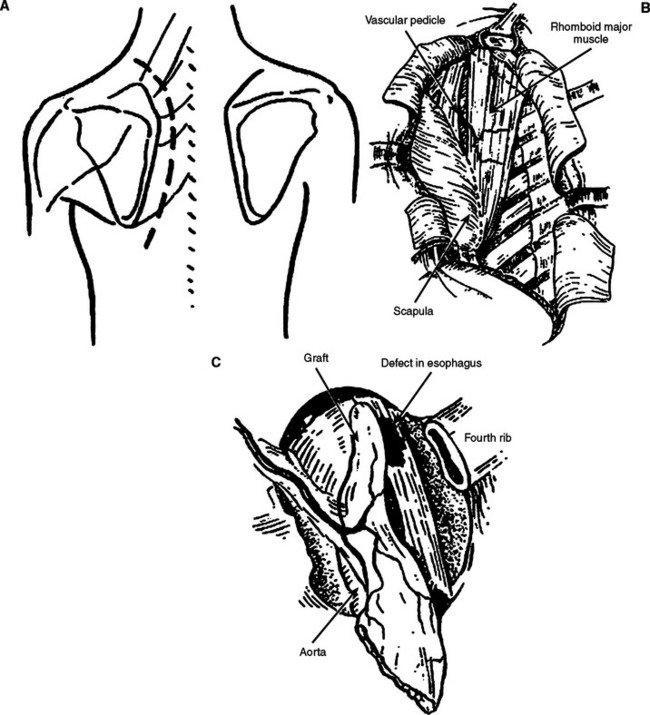

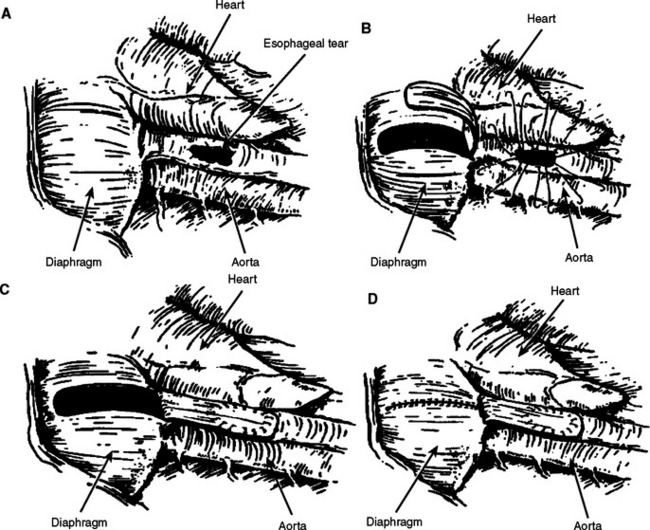

We have demonstrated that injuries to the esophagus involving up to two-thirds of the circumference can be adequately closed with muscle flaps without increased incidence of stricture. The rhomboid muscle may be mobilized for repair of upper- and mid-esophageal injuries (Figure 1). The muscle is dissected from its attachment of the scapula through a parascapular incision and transferred as a pedicle flap into the thoracotomy. For distal esophageal lesions that are too proximal to be buttressed with the gastric fundus, we advocate the use of a diaphragm muscle flap (Figure 2). The central portion of the diaphragm is excised as a pedicle flap and sutured over the defect or buttressed to the repair. The flap should be posteriorly based and great care should be taken to avoid the phrenic nerve. Diaphragm pedicle flaps may reach to the level of the azygous vein. The edges of the diaphragm are then reapproximated with heavy nonabsorbable sutures. A two layer closure is performed if feasible. This has the additional benefit of plicating the diaphragm.

ABDOMINAL ESOPHAGUS

Injuries to the abdominal esophagus are often accompanied by extensive intra-abdominal or intrathoracic injuries. These injuries are best approached through a laparotomy incision with the left chest prepped into the operative field should a thoracotomy be necessitated. Perforations or injuries to the distal esophagus should be closed primarily in two layers with nonabsorbable sutures. The layered closure should then be buttressed with either a Nissen fundoplication over a 50–60 French bougie, a “Thal” patch, or with a diaphragm flap. Injuries that are not amenable to primary closure should be primarily closed with the diaphragm flap. The area of repair should be adequately drained with a silastic tube drain. A gastrostomy tube should be placed for gastric decompression, and a jejunostomy tube should be placed for distal enteric feeding.

DEVASTATING INJURIES

Esophageal resection may be indicated in some unusual circumstances, but the senior author has never been forced to resect the esophagus for trauma in 30 years of experience. Clearly, injuries to a damaged esophagus or caustic injuries may require emergency esophagectomy. If this unusual circumstance arises, delayed reconstruction using stomach or colonic bypass would likely be the treatment of choice.

MANAGEMENT OF COMPLICATIONS

Increased morbidity from diagnostic delays and subsequent delays in operative treatment has been well established. However, little literature exists addressing long-term complications and esophageal function after traumatic esophageal injuries. Certainly, the most concerning complications associated with esophageal injuries are major vascular or airway injuries producing massive hemorrhage or acute respiratory decompensation. The development of anastomotic leaks with subsequent mediastinitis, sepsis, and pulmonary failure presents significant management challenges. Shock, extensive mobilization, inadequate debridement, and tension are well-known risk factors for suture line breakdown and subsequent esophageal leakage. Approximately 50% of esophageal leaks are asymptomatic being noticed only on post-operative esophagograms. Once a leak is identified, the initiation of adequate drainage, wide-spectrum antibiotics, parenteral or distal enteral nutrition, and limited oral intake are the mainstays of therapy. The development of interventional radiological techniques with the advent of percutaneous drainage has certainly assisted in the management of these complicated injuries. Most leaks will subsequently resolve without the need for further operative intervention. Increasingly, endoluminal stents have been used to manage esophageal leaks. We have no experience using stents as primary treatment, but we have used them on two occasions for the treatment of delayed leaks resulting from trauma.

Andrade-Alegre R. T-tube intubation in the management of late esophageal perforations: case report. J Trauma. 1994;37:131-132.

Asensio JA, Berne J, Demetriades D, et al. Penetrating esophageal injuries: time interval of safety for preoperative evaluation—how long is safe? J Trauma. 1997;43:319-324.

Asensio JA, Chawan S, Forno W, et al. Penetrating esophageal injuries: multi-center study of the American Association for the Surgery of Trauma. J Trauma. 2001;50:289-296.

Back MR, Baumgartner FJ, Klein SR. Detection and evaluation of aerodigestive tract injuries caused by cervical and transmediastinal gunshot wounds. J Trauma. 1997;42:680-686.

Bufkin BL, Miller JI, Mansour KA. Esophageal perforation: emphasis on management. Ann Thorac Surg. 1996;61:1447-1452.

Cheadle W, Richardson JD. Options in the management of trauma to the esophagus. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1982;155:380-384.

Conn TI E, Hubbard A, Patton G. Management of esophageal injuries. Ann Thorac Surg. 1989;48:309-314.

Glatterer MSJr, Toon RS, Ellestad C, et al. Management of blunt and penetrating external esophageal trauma. J Trauma. 1985;25:784-792.

Grillo HC, Wilkins EWJr. Esophageal repair following late diagnosis of intrathoracic perforation. Ann Thorac Surg. 1975;20:387-399.

Karmy-Jones RC, Wagner JW, Lewis JWJr. Esophageal injury. In: Trunkey DD, Lewis FR, editors. Current Therapy of Trauma. 4th ed. St. Louis, MO: Mosby; 1999:209-216.

Pass LJ, LeNarz LA, Schreiber JT, Estrera AS. Management of esophageal gunshot wounds. Ann Thorac Surg. 1987;44:253-256.

Popovsky J, Lee YC, Berk JL. Gunshot wounds of the esophagus. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1976;72:609-612.

Port JL, Kent MS, Korst RJ, et al. Thoracic esophageal perforations: a decade of experience. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;75:1071-1074.

Richardson JD. Management of esophageal perforations: the value of aggressive surgical treatment. Am J Surg. 2005;190:161-165.

Richardson JD, Flint LM, Snow NJ, et al. Management of transmediastinal gunshot wounds. Surgery. 1981;90:671-676.

Richardson JD, Tobin GR. Closure of esophageal defects with muscle flaps. Arch Surg. 1994;129:541-548.

Riley RD, Miller PR, Meredith JW. Injury to the esophagus, trachea, and bronchus. In: Moore EE, Feliciano DV, Mattox KL, editors. Trauma. 5th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2004:539-552.

Triggiani E, Belsey R. Oesophageal trauma: incidence, diagnosis and management. Thorax. 1977;32:241-249.