CHAPTER 34 Treatment of blepharoplasty complications

History

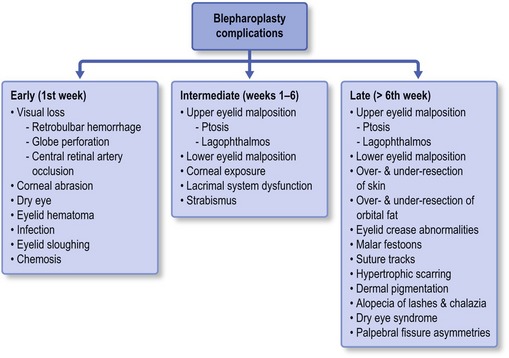

The following chapter presents intraoperative and postoperative complications from blepharoplasty based upon timeframe from surgery and offers guidance for treatment and/or prevention of each. It is important to realize that some complications may arise in multiple time periods postoperatively. Early recognition and appropriate treatment is essential; but the best therapeutic option often differs based upon the timing from surgery. An outline provides an overview of the most common and concerning complications allowing the reader to develop appropriate clinical perspective. This chapter breaks from the standard layout in the textbook in order to offer the clinician a more clinically useful reference for understanding and treating the postoperative blepharoplasty complication (Fig. 34.1).

Complications in the early postoperative period (1st week)

Visual loss

Retrobulbar hemorrhage

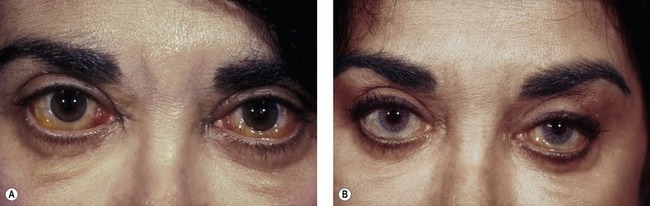

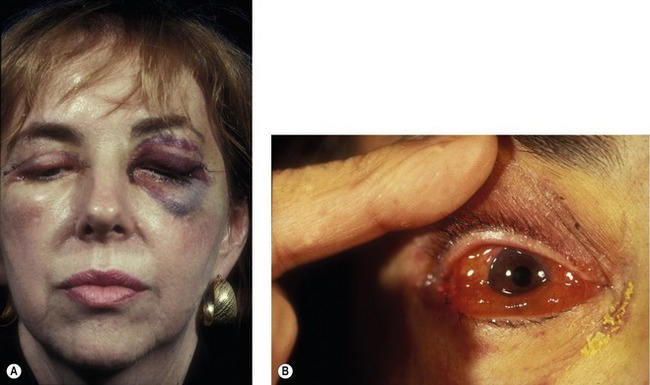

The incidence of retrobulbar hemorrhage was reported in the plastic surgery literature at 0.04%.1 More recently, an epidemiologic study of greater than 250 000 blepharoplasty cases performed by oculoplastic specialists found the incidence of retrobulbar hemorrhage to be 0.05%; associated permanent visual loss was diagnosed in 0.0045%.2 This corresponds to a 1/2000 risk of significant hemorrhage and a 1/10 000 risk of permanent visual loss. Most often clinical presentation is within the first 24 hours after surgery, although bleeding has been reported as late as 9 days after surgery.3 Patients may complain of pain, pressure, diplopia and visual loss. Examination shows decreased visual acuity, lid edema, proptosis, subconjunctival hemorrhage, extraocular motility disturbance, increased intraorbital (resistance to retropulsion) and intraocular (tonometry) pressure and an afferent pupillary defect (Fig. 34.2).

Fig. 34.2 Retrobulbar hemorrhage producing ecchymosis after a frontal nerve block during transcutaneous blepharoplasty (A) and retrobulbar hemorrhage in a hypertensive patient demonstrating sudden proptosis and chemosis (B).

Pearls

Pearls to avoiding retrobulbar hemorrhage include:

• Detailed preoperative evaluation with particular attention to medical problems such as diabetes, hypertension, coagulopathies and both prescription and over-the-counter anticoagulant medication use. Stopping all anticoagulants far enough in advance to allow normalization of bleeding parameters and platelet function is important.

• A past ocular history is necessary to rule out pre-existing causes of visual dysfunction, as rare reports of malpractice cases where patients have claimed pre-existing visual loss as a consequence of blepharoplasty do exist.

• Intraoperative control of hemostasis is critical. Koorneef’s description of the delicate connective tissue scaffold connecting the anterior orbital fat to deep orbital fat underscores the necessity to avoid excessive traction during fat excision. It is advantageous to delay wound closure by proceeding to another surgical site, returning later to reassess hemostasis prior to suturing.

• Postoperative prevention of hemorrhage involves all of the following:

Once the diagnosis of retrobulbar hemorrhage is made, the treatment requires immediate attention. The first step should be to identify those hemorrhages that require medical or surgical care, based on the ophthalmic examination. If the intraocular pressure is elevated, as measured by tonometry or emergently by tactile evaluation, topical and systemic glaucoma medications can be used. Systemic corticosteroids are used for significant edema. When the bleeding threatens the visual system, or is worsening, surgical therapy is required. The first step is to open the incision widely through the orbital septum and explore the surgical site and orbit for signs of bleeding. Clots are evacuated and cautery is applied when bleeding sites are identified. If the condition remains unresponsive, a lateral canthotomy and cantholysis is performed. In severe cases, both the inferior and superior crus of the lateral canthal tendon can be released. When these measures fail, an emergent CT scan without contrast is warranted. If posteriorly organized hemorrhage is identified, bony decompression may be warranted to relieve orbital apex compression (Fig. 34.3). The treatment should be aggressive for the first 24–48 hours postoperatively, as vision has been reported to return in patients with “no light perception” that was present for 24 hours.

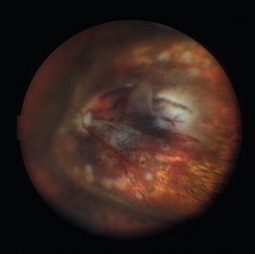

Globe perforation

Inadvertent globe penetration can result from any periocular procedure. Caution is necessary during local anesthetic injection, particularly in the thin upper eyelid of older patients. Prevention of this complication begins with the use of protective corneal shields during injection and surgery. Corneal shields should be lubricated with ophthalmic ointment prior to placement within the lids to avoid corneal abrasion. The range of potential ocular damage from penetration includes an open globe, corneal perforation, traumatic cataract, intraocular hemorrhage, a hypertensive or hypotensive globe, retinal tears and detachment (Fig. 34.4). Perforation of the globe is an ophthalmic emergency and necessitates emergent consultation with an ophthalmologist. A Fox shield should be placed over the eye in the interim and the patient should be instructed not to rub or press on the eye.

Corneal abrasion

Corneal abrasion is generally a rapidly reversible cause of decreased vision postoperatively. The diagnosis is made by patient symptoms (pain, foreign body sensation, light sensitivity) and is usually apparent immediately after surgery. The diagnosis is confirmed by evaluating the cornea under a cobalt blue light after instillation of fluorescein (Fig. 34.5). Even though corneal abrasion is the leading cause of ocular pain and irritation following blepharoplasty, patients who complain of severe eye pain should be carefully examined under a slit-lamp to rule out globe perforation. Abrasions are often caused by drying of the corneal surface during surgery or inadvertent damage to the surface corneal epithelial layer. Sometimes, taping of the eyes during anesthetic induction causes an abrasion if the eyes are accidentally taped in an open position. Careful insertion and removal of well-lubricated corneal shields prevents this complication; as does the use of ophthalmic ointment into each eye at the completion of the procedure. Abrasions can be treated with ophthalmic antibiotic ointment four times daily, and should be resolved within 24 hours. Patching should be avoided, as it may mask a more serious complication, such as retrobulbar hemorrhage. Persistent signs and symptoms should prompt ophthalmologic evaluation.

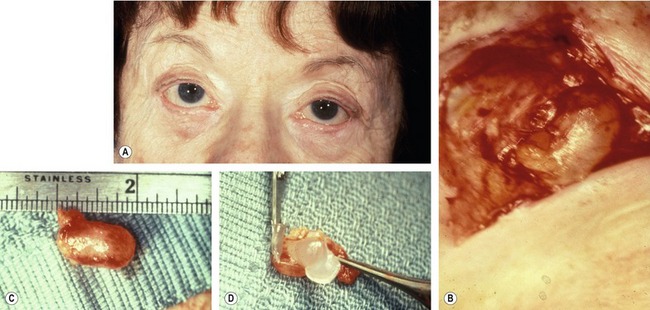

Dry eye

Very rarely, ophthalmic lubricant may be inadvertently introduced into deeper eyelid tissues from a transconjunctival surgical wound. This can result in encapsulation of the ointment within the wounds, and subsequent cyst formation that responds to excision (Fig. 34.6). Although this complication is extremely rare, physicians should keep in mind that excessive amounts of ointment are unnecessary and may result in inoculation of the wound.

Infection

The development of cellulitis or abscess formation is exceedingly rare in the well-vascularized eyelid. Nonetheless, both complications have been reported and should be managed with appropriate oral or intravenous antibiotics. Abscesses require surgical drainage. Figure 34.7 shows a patient who developed pseudomonas cellulitis in three of four lids after blepharoplasty. She was treated with a combination of surgical drainage and intravenous antibiotics, but ultimately developed late cicatrization and skin dimpling.

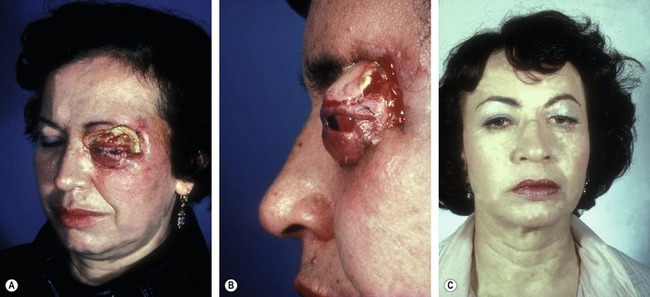

Eyelid sloughing

Eyelid necrosis has been reported sparingly in the literature and can follow inadvertent injection with formaldehyde or other substances (i.e. atropine, alcohol, boric acid) instead of local anesthetic. Complete eyelid sloughing can develop, necessitating multiple eyelid reconstructive procedures and setting the patient up for scarring, persistent lagophthalmos and chronic ocular irritation from dry eye (Fig. 34.8).

Chemosis

Conjunctival edema can develop in the early or intermediate postoperative period as the result of incomplete eyelid closure, ocular allergy, sinusitis or surgical edema. Chemosis can be worsened by systemic conditions, such as renal failure (Fig. 34.9). Corneal drying may occur, as the edematous conjunctiva balloons around the cornea preventing adequate tear film dispersion. Additionally, the exposed conjunctival surface may keratinize, leading to worsening foreign body sensation and ocular irritation. Treatment is with preservative-free artificial tears and ointment. A mild topical steroid eye drop can be prescribed, but should only be given in conjunction with ophthalmic evaluation to assure normalcy of the intraocular pressure and to rule-out secondary infectious keratitis. Rarely, a temporary suture tarsorrhaphy may be needed.

Complications in the intermediate post-operative period (1st–6th week)

Upper eyelid malposition

Ptosis

Postoperative ptosis can be seen frequently following upper eyelid blepharoplasty (Fig. 34.10). Often, this subtle levator attenuation seen in aponeurotic ptosis is present preoperatively, but goes undiagnosed.7

Pearls

Pearls for avoiding overlooking preoperative ptosis include:

• Assure that the frontalis muscle is blocked when examining the upper eyelid position. Often patients with ptosis and/or excessive dermatochalasis compensate with involuntary frontalis recruitment.

• Carefully examine the margin reflex distance (MRD), palpebral fissure height (PF), levator function and upper eyelid crease height. Patients with excess upper eyelid tissue overhanging may mask a small MRD and PF distance. Aponeurotic ptosis is often accompanied by an increase in lid crease height, or a deep superior sulcus.

• When measuring MRD and PF, simultaneously block the frontalis muscle and mechanically lift the excess tissue.

• Plan a concomitant ptosis surgery along with blepharoplasty, if necessary.

Mechanical ptosis can result from postoperative edema or ecchymosis. This should resolve with conservative treatment, including cool compresses. If the ptosis remains persistent, it is possible that the edematous state led to levator attenuation; or, the patient may have developed a neurogenic ptosis. When persistent, the surgeon should consider ophthalmic evaluation.

Lagophthalmos

• Surgical trauma to the orbicularis muscle.

• Tethering of the eyelids by sutures or Steri-Strips (3M, St. Paul, MN).

• Postoperative pain, leading to guarding and incomplete lid closure (Fig. 34.11).

Inadequate eyelid closure can lead to patient discomfort secondary to exposure keratopathy. The condition will be worsened in those with pre-existing dry eye disease or the absence of an adequate Bell’s phenomenon (Fig. 34.12). Preoperative evaluation should include an assessment of ocular sicca symptoms (foreign body sensation, tearing, irritation, photophobia and dryness), signs (abnormal tear film, punctate corneal staining and decrease in basal tear secretion) and adequacy of the Bell’s reflex. Lagophthalmos is usually temporary and conservative management in the intermediate postoperative period includes frequent lubrication, lid massage and lid taping.

Lower eyelid malposition

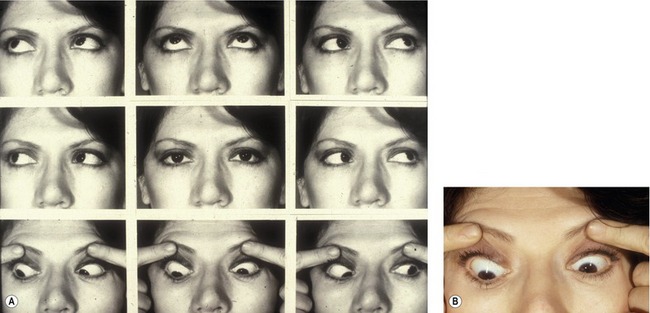

The most common reported complication after lower eyelid blepharoplasty is lower eyelid malposition, which may range from mild inferior scleral show (Fig. 34.13A) in up to 20% of patients to severe cicatricial ectropion (Fig. 34.13A,B) in 1%.8,9 Lid malposition is the result of an imbalance in lower eyelid forces. Abnormal downward forces can result from excessive skin resection, scarring, imbrication of the orbital septum, edema and hematoma. Laxity of the tarsoligamentous sling causes a loss of normal upward traction and dynamic elasticity of the lower lid. Orbicularis oculi paralysis additionally destabilizes the lower eyelid position.

While cases of over-resection of skin have become less common with the popularity of transconjunctival blepharoplasty, a role still exists for the transcutaneous blepharoplasty, making the potential for excess skin resection real. If over-resection is diagnosed early, skin sutures can be removed at 2–3 days postoperatively, and the wound gapped, allowing granulation of a portion of the eyelid. While not ideal, this option is better than the severe bowing or ectropion that is likely to result and will often necessitate skin grafting. Similar wound gapping can be performed with acceptable results in the upper eyelid. Massage is needed during granulation to stretch and counter the forces of contraction.

Corneal exposure

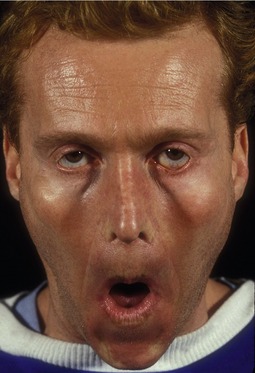

As in the early postoperative period, keratopathy may persist or become evident during the intermediate recovery period. Similar to patients with early corneal irritation, sutures or Steri-Strips may be tethering the eyelids since the orbicularis muscle may not have regained its protractor abilities. Additionally, over-resection of skin may become more apparent as initial postoperative edema resolves. First line treatment is generally expectant, with frequent ocular lubrication and taping, if necessary. One condition worth mentioning is the patient with undiagnosed thyroid ophthalmopathy who undergoes blepharoplasty and unmasks lid retraction and keratopathy (Fig. 34.14A&B). If necessary, the wound can be opened and allowed to granulate (Fig. 34.14C&D). Further treatment options are usually reserved for later in the postoperative course.

Strabismus and extraocular muscle disorder

Diplopia is a rare, but potentially disabling complication of upper or lower eyelid blepharoplasty. It is common for patients to complain of intermittent double vision following blepharoplasty, often secondary to an abnormal tear film, ophthalmic ointment, muscle contusion or temporary paresis, hematoma or edema. Signs that make diplopia less worrisome following surgery are:

• Preoperative history of strabismus and diplopia.

• Diplopia that clears with blinking (suggestive of precorneal tear film abnormality).

Such patients should be treated with reassurance and preservative-free artificial tear drops.

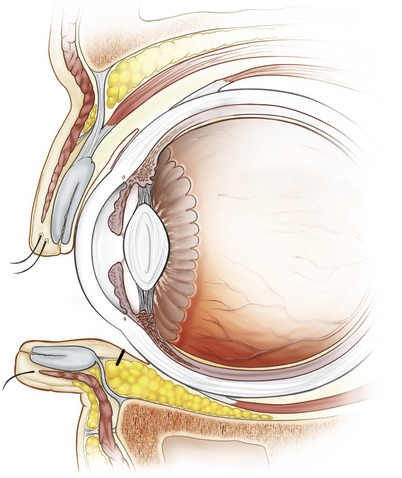

Persistent binocular diplopia requires additional consideration, especially if vertical. Transconjuctival and transcutaneous lower eyelid blepharoplasty can each result in iatrogenic strabismus.10 In both surgical approaches, the inferior oblique muscle is most commonly injured (Fig. 34.15). Damage may be direct, or secondary to aggressive cautery in the region between the nasal and central fat pockets. Some surgeons advocate identification of the inferior oblique muscle during fat resection under direct visualization, but realistically this is not likely, since most blepharoplasties are performed by non-ophthalmologists. Additionally, secondary blepharoplasty increases operative risk as anatomic identifiers may be ambiguous and fibrosis is often encountered.

Pearls

Pearls to avoid damage to the inferior oblique muscle:

• The most direct route to the extraocular musculature is through a deep forniceal incision. Avoiding this deep forniceal incision is crucial. The ideal location of an incision is approximately 5–6 mm inferior to the inferior tarsal border on the palpebral conjunctiva (Fig. 34.16).

• When in doubt, or as a routine, the inferior oblique muscle can be identified lying between the nasal and central fat pockets in the lower eyelid.

• Any clamping or traction on fat should not move the globe. If this occurs, suspect that an extraocular muscle is intertwined with the proposed resection and reevaluate.

The superior oblique muscle can be injured during upper eyelid blepharoplasty, with mechanisms of injury similar to inferior oblique damage. Injuries to the inferior and lateral recti are exceedingly rare, but have been reported. The inferior oblique muscle rides over the inferior rectus muscle, making damage to the rectus less likely.

Complications in the late postoperative period (7th week and beyond)

Upper eyelid malposition

Lagophthalmos

Lagophthalmos in the late postoperative period is the result of excessive skin excision or incorporation of the orbital septum in skin closure resulting in eyelid retraction. Initial therapy was described previously. If conservative therapy fails, surgical correction should be considered at approximately three months postoperatively. Surgical options include elevation of the lower eyelid, skin grafting or release of orbital-septal adhesions. Because of the aesthetic considerations in skin grafting, lower eyelid elevation is often attempted first. If necessary, skin grafts are best harvested from the opposing upper eyelid. Secondary choices include the retroauricular and supraclavicular space. Recently, oculoplastic surgeons have found success with a full thickness blepharotomy for upper eyelid retraction in thyroid related ophthalmopathy. This procedure, originally described by Koorneef, has been reported to be successful in post-blepharoplasty retraction11 and may have an increased role in years to come.

Lower eyelid malposition

An anterior lamellar deficiency is encountered after transcutaneous blepharoplasty and can best be diagnosed by noting lower eyelid movement with opening of the mouth (Fig. 34.17). Frank cicatricial ectropion can develop (Fig. 34.18A). Most disease states respond partially or completely to eyelid stretching (Fig. 34.18A&B). Placing the eyelid on stretch as early as possible is advisable. Surgical repair often involves placement of additional skin to replace the deficient lamella. A combined lateral tarsal suspension is appropriate if concomitant horizontal laxity is present. Tarsal suspension may be done alone as an indirect secondary procedure in those patients who are unhappy with the thought of skin grafting. These patients often require over-correction since gravity and midfacial movements will loosen the original position attained.

Middle lamellar deficiency is diagnosed by attempting to stretch the central aspect of the lower eyelid superiorly. A normal response is the ability to easily elevate the lower eyelid over the inferior corneal limbus. If the eyelid will not elevate, adhesions are present between the capsulopalpebral fascia and the orbital septum or the anterior tissue and the orbital septum. Successful repair in these instances requires lysis of these adhesions if conservative stretching has failed. A lateral fixation procedure or occasionally posterior lamellar lengthening may be necessary.

Over and under-resection of orbital fat

Over-resection

Overzealous fat resection can result in a hollow, skeletonized look that is aesthetically unappealing. Conservative resection is the best preventative measure. When over-resection occurs, options for correction include fat transposition or grafting, midface lifting and injection of fillers. In the instance where enough fat remains in a different area of the lid, fat transposition may ameliorate an isolated hollow. Free fat grafts are often complicated by resorption of the additional tissue. Midface lifts may camouflage the defect by enhancing the malar eminence. Periocular fillers, such as hyaluronic acid gel, may have a role for filling hollows. The ability to perform injections in the office setting is advantageous, but patients may experience lumps, bruising, color change and fluid accumulation. Additionally, the treatment is temporary and patients must be counseled on the need for recurrent injections.12 Lateral canthoplasty has a significant role since posterior pressure on the globe will anteriorly displace any remaining fat to soften the hollows.

Under-resection

Pearls

Pearls for avoiding inadequate fat resection:

• In the upper eyelid, the medial fat pocket is least accessible and may be inadequately addressed at the time of surgery. The medial fat pocket can be identified as a distinctly ‘whiter’ fat than the central pad. Identification of the medial fat is the first step towards its adequate resection.

• The lateral fat pocket is most commonly missed in lower lid blepharoplasty and is seen postoperatively as a lateral bulge (Fig. 34.19). There is a greater amount of connective tissue septae covering this pad. Excision of the superficial septae and fat allow additional prolapse of deeper fat with mild pressure on the globe. It is common to reherniate the lateral pocket if canthoplasty is performed concurrently. Attention should be directed to re-evaluate the lateral pocket if canthal tightening procedures are performed.

Eyelid crease abnormalities

Symmetry and reformation of the upper eyelid crease may be the single most important factor in a successful upper eyelid blepharoplasty outcome.13 The crease in women should be higher than in men, allowing adequate pre-tarsal show. Additionally, a women’s crease is more sharply demarcated. In men, some fullness should be left in the upper lid to allow the upper eyelid fold to cover the crease. When patients notice crease asymmetries, it is usually due to unilateral brow elevation with ptosis which elevates eyebrow skin superiorly.

Malar festoons

The best prevention of malar bags is to diagnose them preoperatively or to recognize patients who are at increased risk. Patients with mild malar festoons should be questioned about a history of thyroid disease, renal failure, chronic sinusitis, allergies and idiopathic edema. Patients who are predisposed to fluid accumulation should be advised of the risk of developing postoperative malar bags. Preoperative consultation with an internist is advised, as postoperative care often involves systemic steroids and/or diuretics. Patients who are at higher risk should be treated intra-operatively with intravenous steroids. Postoperative steroids (i.e. medrol dose packs) are useful. Furosemide (Lasix) 20 mg or 40 mg daily early in the postoperative course is helpful (Fig. 34.20). With time, this agent can be replaced with a milder diuretic, such as hydrochlorothiazide 50 mg per day. Medical treatment is continued for 7–10 days. While persistent malar festoons can be excised, the success rate is low, as patients are again at risk for retained fluid. If the underlying condition is systemic, eyelid surgery cannot locally correct the problem.

Fig. 34.20 Pretreatment (A&C) and post-treatment (B&D) examples of malar bags responding to diuretic therapy. Each patient was treated with furosemide and potassium replacement. Time alone may have produced the same result, but Lasix treatment plays a role in minimizing the stretching and attenuation of malar and lower eyelid skin.

Suture tracks

Epithelial trapping can occur along suture tracks.

If present, suture tunnels can be unroofed with a fine needle or surgical blade. Light cautery may be applied.

Dry eye syndrome

• Assessment of dry eye symptoms.

• History of dry eye disease, Sjogren’s syndrome or prior refractive surgery.

• Current use of lubricating eye drops and ointments.

• Slit lamp examination with fluorescein staining.

• Basal tear secretion testing with Schirmer Strips (Eagle Vision, Memphis, TN).

A small subgroup of preoperative patients with dry eye and very heavy upper eyelids are actually improved by removal of excess skin.14 In these cases, the eyelashes are pushed inferiorly due to fullness. Normal desquamation of the upper eyelid epithelium falls into the palpebral aperture producing the symptoms of dry eye without the physiologic findings of lacrimal, meibomian gland or goblet cell dysfunction.

1. DeMere M, Wood T, Austin W. Eye complications with blepharoplasty or other eyelid surgery. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1974;53(6):634–637.

2. Hass AN, Penne RB, Stefanyszyn MA, Flanagan JC. Incidence of postblepharoplasty orbital hemorrhage and associated visual loss. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;20(6):426–432.

3. Teng CC, Reddy S, Wong JJ, Lisman RD. Retrobulbar hemorrhage nine days after cosmetic blepharoplasty resulting in permanent visual loss. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(5):388–389.

4. Koorneef L. Orbital septa: anatomy and function. Ophthalmology. 1979;86:876–880.

5. Castillo GD. Management of blindness in the practice of cosmetic surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1989;100:559–562.

6. Campbell JP, Lisman R. Complications of blepharoplasty. Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am. 2000;8(3):303–327.

7. Lowry JC, Bartley GB. Complications of blepharoplasty. Surv Ophthalmol. 1994;38:327–350.

8. Baylis HI, Long JA, Groth MJ. Transconjunctival lower eyelid blepharoplasty: technique and complications. Ophthalmology. 1989;96:1027–1032.

9. McGraw BL, Adamson PA. Postblepharoplasty ectropion: prevention and management. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:852–856.

10. Ghabrial R, Lisman RD, Kane MA, Milite J, Richards R. Diplopia following transconjunctival blepharoplasty. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102(4):1219–1225.

11. Demirci H, Hassan AS, Reck SD, Frueh BR, Elner VM. Graded full-thickness anterior blepharotomy for correction of upper eyelid retraction not associated with thyroid eye disease. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2007;23(1):39–45.

12. Goldberg RA, Fiaschetti D. Filling the periorbital hollows with hyaluronic acid gel: initial experience with 244 injections. Ophthal Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;22(5):335–343.

13. Shorr N, Cohen MS. Cosmetic blepharoplasty. Ophthalmol Clin North Am. 1991;4:17–33.

14. Vold SD, Carroll RP, Nelson JD. Dermatochalasis and dry eye. Am J Ophthalmol. 1993;115(2):216–220.