Chapter 29 Treatment by Open Surgical Techniques

Introduction

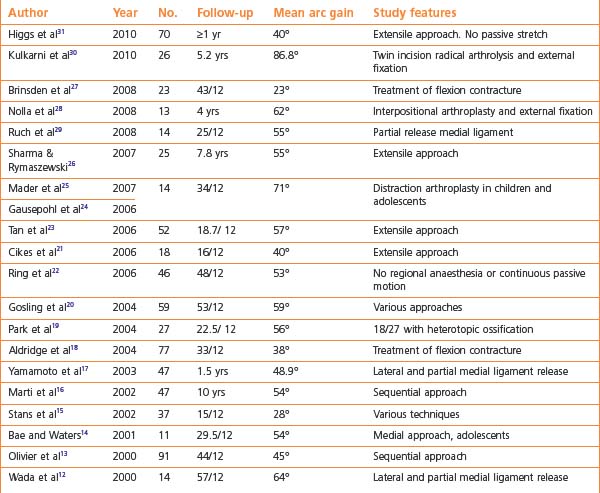

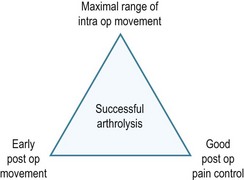

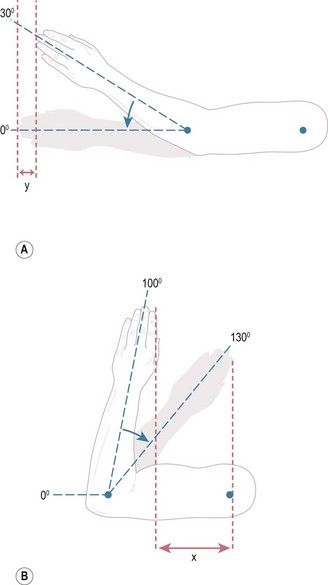

Surgical release of posttraumatic stiff elbows was rarely performed until approximately 15–20 years ago, as the procedure was generally considered to be ineffective in restoring motion. However, following numerous reports of successful results1–31 arthrolysis is now regarded as a reliable, rewarding, evidence-based operation with low risk of complications. The results in the recent literature12–31 are broadly similar, reporting that elbow motion improves in nearly all patients, with a mean gain of 52° (Table 29.1), and that the majority achieve the functional arc of 30–130°. The key principles common to nearly all papers were achievement of as much movement as possible at surgery, and early motion postoperatively which required adequate pain control (Fig. 29.1).

Controversy still remains regarding what constitutes optimal management, as a wide variety of different operative procedures and postoperative regimens have been described.1–34 These surgical techniques range from arthroscopic procedures, through increasingly extensive open releases up to requiring a dynamic external fixator to provide stability. Postoperative passive stretching with manipulation35 or splinting36 is often advocated, but may be counter-productive if painful. This chapter gives an overview of the current situation, and proposes a new surgical guide to aid with the management of stiff elbows.

Presentation, investigation and treatment options

Open arthrolysis is indicated for patients with a functional deficit due to significant elbow stiffness which has failed to improve over a 6–9-month period. Usually, the restriction is less than 120° of flexion and greater than a 40° flexion contracture, and/or 50° restriction of forearm rotation. However, some can cope satisfactorily with considerably less movement than the ‘functional arc’ of 30–130°,37 especially in the non-dominant arm. Occasionally and conversely, a patient may be unable to perform certain activities at work or sport despite relatively mild restriction of motion.

The decision to proceed to arthrolysis must be made on an individual basis, with clarity regarding the aims of surgery and the likelihood of meeting the patient’s expectations. A summary of the indications for arthrolysis is given in Box 29.1. Factors such as a major head injury, contralateral upper limb and multiple injuries, as well as burns and prolonged artificial ventilation have a detrimental effect on outcome, whether or not surgery is undertaken.20

Age

The average age at which arthrolysis was undertaken over the past decade was 36 years, ranging from 8 to 76 years.12,13,16–23,26–31 Arthrolysis in the skeletally immature elbow has been successful,14,15 although Stans et al24 reported a tendency towards less favourable outcomes compared with adults. Caution should be exercised when considering arthrolysis in children, especially when the parents are anxious and keen on surgery. A child usually has little problem coping with a stiff elbow, and the potential for improvement with time and use is considerable. The adolescent may request intervention on cosmetic as well as functional grounds, and it is again important to address any unrealistic expectations.

Time from injury

The timing of arthrolysis is controversial as the natural history of posttraumatic elbow stiffness is of gradual improvement with use, up to at least 6 months after injury, although some individuals continue to improve significantly for up to and even beyond 1 year. Some surgeons believe that a shorter interval from trauma to arthrolysis, usually within 1 year, is associated with superior outcomes, both in terms of ROM and functional scores.13,17,18,34 Others12,15,33 have found no correlation, and therefore, arthrolysis should be considered only when the patient’s ROM on serial goniometric measurements and function has plateaued. In the presence of heterotopic ossification, surgery should be postponed until it is radiologically mature.

Severity of stiffness

Paradoxically, the greatest improvement in motion may be achieved in elbows with the greatest restriction, despite significantly damaged articular surfaces;4,21,33 for example Morrey4 reported six elbows whose movement improved by 80° (27–107°) following release, interposition and distraction. We found a similar improvement in seven patients with severe stiffness (mean 21° arc of motion), who achieved a mean gain of 79° following open arthrolysis, but without interposition or distraction.31 Clearly overall, a greater gain in the arc of movement results in better functional outcome and patient satisfaction. Patients are usually happy to exchange a painless, ankylosed joint for a mobile elbow even if this results in a degree of discomfort or pain. In the subgroup of patients whose main complaint is of generalized pain rather than stiffness, arthrolysis is still likely to result in a modest improvement in motion, although there is a risk that pain remains unaffected.

History

Posttraumatic stiffness is not usually painful.38 If pain is present, it tends to occur only at the extremes of flexion/extension due to impingement, with repeated movements or on loading, for example when lifting a heavy weight. Pain due to rotational movements, for example turning a stiff door knob or using a screwdriver, is indicative of radiocapitellar pathology. Less commonly, pain is experienced throughout the arc of elbow motion due to intra-articular incongruity or degeneration. Serious pathology including infection, inflammatory disease or tumour should be considered if severe pain is experienced at rest or at night, especially if the patient is systemically unwell. Occasionally but rarely, severe elbow pain and spasm can occur as a result of a regional pain syndrome, which will also affect the shoulder, wrist and hand. It is especially important to enquire if ulnar paraesthesia, sensory loss, weakness and/or clumsiness are present, as decompression or transposition of the ulnar nerve is essential to avoid disappointing results.22 Mechanical symptoms, such as catching and locking, may also be present, indicating the presence of loose bodies (Box 29.2).

Examination

The ROM should be accurately measured and recorded at each visit in a standard fashion, ideally by the same examiner, as failure of progression on serial measurements can then be identified and arthrolysis considered. Measurements of flexion and extension are standardized by using a long-arm goniometer centred over the lateral epicondyle, giving an acceptable error of 10°.39 Restriction of active and passive ROM to the same degree is the hallmark of bony impingement. A hard endpoint indicates a bony block, while a soft endpoint is more likely to be due to a soft tissue contracture. Impingement pain at the extremes of motion is the most common finding, with significant mid-range pain being unusual, even if articular damage exists. Supination and pronation must also be recorded.

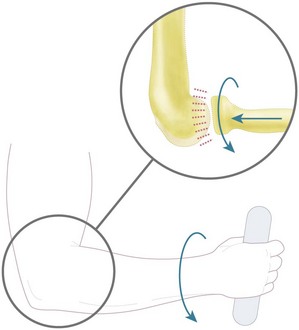

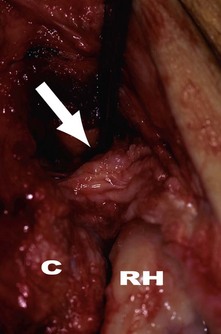

Pain and/or crepitus due to radiocapitellar arthritis are usually the result of a previous radial head fracture and are reliably elicited with the ‘grip and grind’ test. This is performed with the patient applying an axial load by gripping while rotating their forearm, thus loading the radiocapitellar joint (Fig. 29.2). A positive test reproducing the patient’s symptoms indicates that surgery to the radial head will be required.

Surgical treatment options

Several surgical options are available apart from open arthrolysis.

Arthroscopic arthrolysis

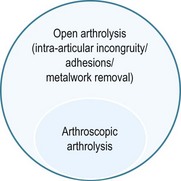

Arthroscopic arthrolysis is described in Chapter 30. Advocates of this method point out that statistically significant improvement in ROM can be safely achieved by this technique,33,34 facilitating early mobilization and discharge.32 Arthroscopic techniques, are however, more difficult in cases of severe contracture or where previous surgeries have been undertaken, particularly when there is internal fixation in situ. The ulnar nerve may also be affected requiring decompression/transposition. In addition patients with significant flexion loss may require release of the posterior bundle of medial collateral ligament which cannot be achieved arthroscopically.31 Finally, incongruous joint surfaces with extensive intra-articular adhesions may require a complete lateral ligament complex/extensor origin release to be able to separate the joint surfaces with supination giving an adequate exposure for satisfactory correction. Arthroscopic arthrolysis can therefore only be used in selected cases (Fig. 29.3), and the technique is demanding with a steep learning curve. Open arthrolysis is therefore the simplest, safest, most effective method for the majority of patients with stiff elbows.

Interpositional arthroplasty and mechanical distraction

Interpositional arthroplasty has been advocated in the younger patient with arthritis, particularly when there is more than 50% loss of the articular surface. Interposition with tissue such as autologous fascia lata or allogenic Achilles tendon can be used to resurface the joint and a dynamic external fixator applied for protection of the repaired or reconstructed ligaments. Morrey4 demonstrated an average flexion arc increase of 67° in 14 patients treated with distraction arthroplasty and 80° in six treated with distraction arthroplasty and interpositional grafting, although there was a significant complication rate. Overall, there is little evidence that interpositional arthroplasty adds value to arthrolysis alone with regard to ROM, pain relief or functional scores at a mean follow-up between 4 and 5 years.15,27,40 In addition, there is a significant risk of instability, presumably due to the greater release required to secure the interposed material.27,40

Distraction arthroplasty has also been described for the treatment of posttraumatic stiffness of the elbow in children and adolescents.24 This technique involves intraoperative distraction with an external fixator, a relaxation phase of less than 1 week, followed by mobilization of the elbow in a dynamic external fixator for several weeks. The authors have demonstrated that mechanical distraction results in statistical significant improvements in elbow ROM but not other outcome measures.24

Total elbow replacement (TER)

There is very limited evidence for the use of TER in the ankylosed joint. Replacement should be considered as a salvage procedure only in the older, less active patient. Patients should be made aware of the risks and postoperative limitations. In the presence of poor bone stock, severe deformity or instability, a linked prosthesis is recommended. Mansat and Morrey1 demonstrated an average improvement of 60° in 13 severely stiff elbows at an average of 63 months. Ten (77%) were satisfied, however there were 7 (54%) complications including 2 deep infections. Throckmorton et al2 established there was a significantly higher rate of failure in those aged less than 65 years, with 75% of failures occurring in this group and concluded that long-term survival rates for TER in the posttraumatic stiff elbow are less than for rheumatoid arthritis.

Surgical techniques

The main aim of open arthrolysis is to achieve as near to a full range of elbow flexion, extension and forearm rotation as possible during the operation. This is essential as the final range of movement is never more than that obtained at surgery, and is likely to be at least 10° less in any direction. A variety of open surgical approaches have been reported,12–31 each with specific advantages and disadvantages. The method chosen will be determined by a preoperative assessment of the pathology and the personal preference of the surgeon. However, any exposure must be extensile if a satisfactory ROM cannot initially be achieved, using supplementary incisions if necessary.

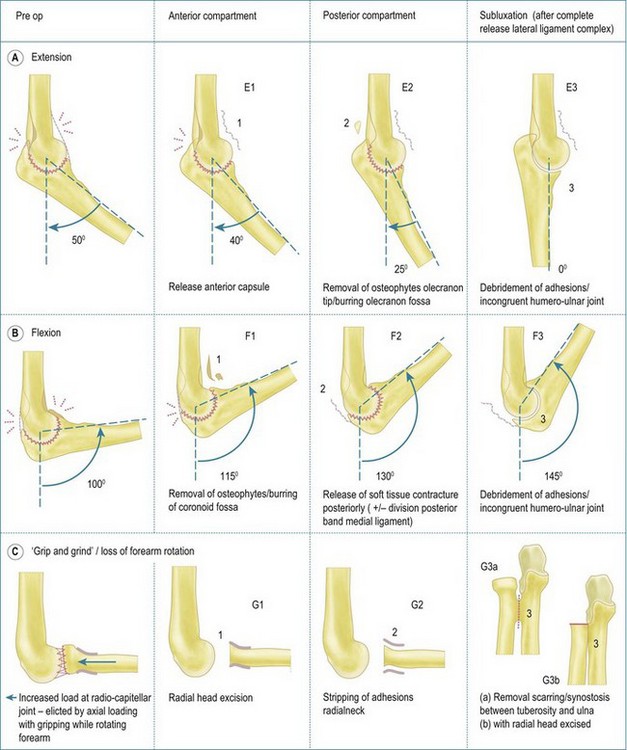

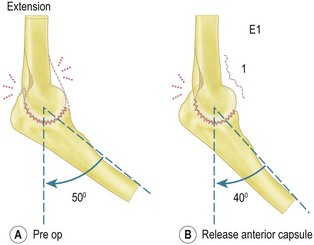

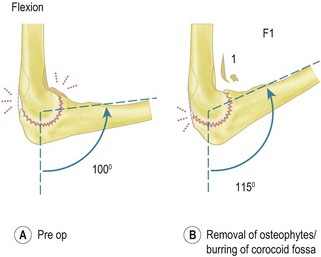

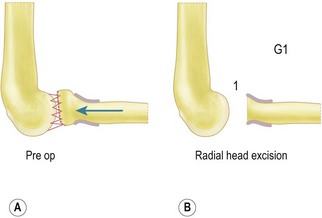

A new ‘extension, flexion, grip and grind’, (EFG) surgical guide is proposed by the senior author (Fig. 29.4). It is based on addressing the pathology responsible for elbow stiffness in a sequential manner with an extensile approach, rather than focusing on individual techniques. In addition, the EFG surgical guide facilitates accurate documentation of the intraoperative findings and can therefore be used as a research tool to allow comparisons between different patient groups, surgical techniques and postoperative regimens.

Clinical Pearl 29.1 At operation – EFG surgical guide

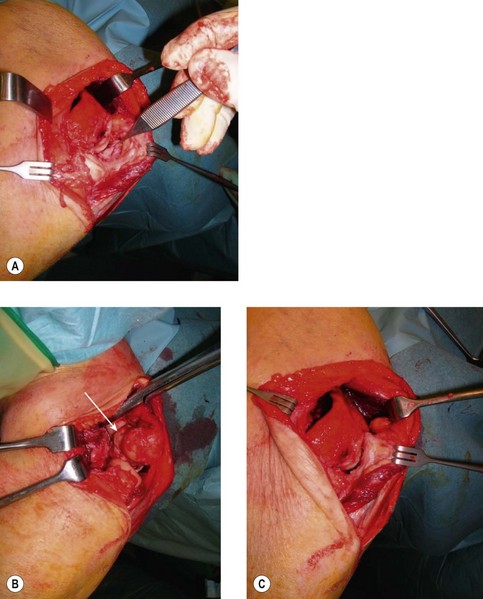

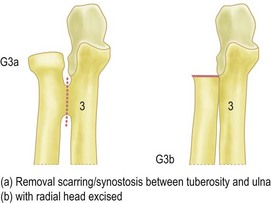

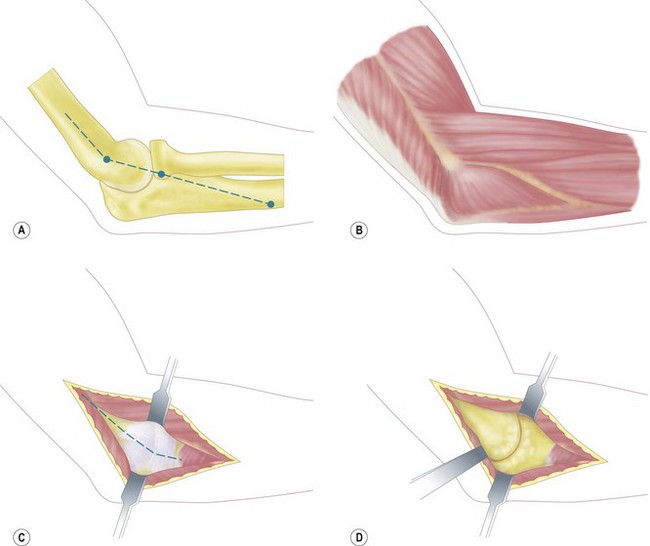

Figure 29.13 (A–D) Kocher lateral approach through anconeus interval to expose radiocapitellar joint.

(Courtesy Dr Praveen Kumar, Consultant Orthopaedic Surgeon, Chennai, India.)

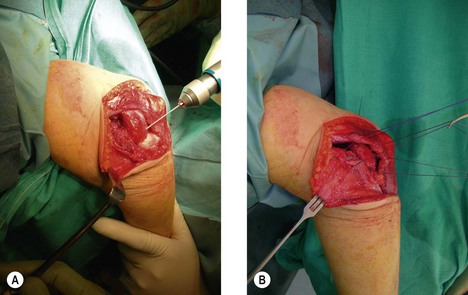

Incision(s)

The siting of incisions is determined by the pathology and surgeon’s preference. Frequently, any scar from previous internal fixation will be utilized, usually posterior or lateral, or occasionally medial. A posterior midline incision with elevation of full thickness skin flaps as far as the epicondyles, or bilateral lateral and medial incisions, allows identical exposure to the ulnar nerve, anterior and posterior capsule and joint via the medial and lateral ridges under brachialis and triceps. Alternatively, a triceps splitting approach gives an excellent view of the olecranon fossa. The anterior compartment can also be accessed to a certain extent by creating a hole in the humerus – the Outerbridge–Kashiwagi (OK) technique. The tip of the coronoid process can also be debrided through the defect when the elbow is flexed. However, if sufficient release has not been achieved, a small additional incision can be made laterally and, if necessary, medially so that all compartments of the elbow joint can be reached.42

Approaches

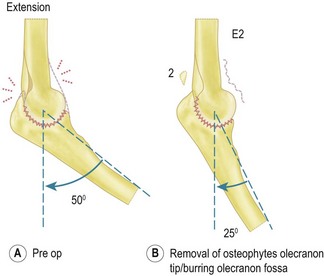

Lateral approach

The ‘column procedure’,11 a limited lateral approach with preservation of the lateral ligament complex, can be used to release the contracted capsule anteriorly and posteriorly. Excision of the radial head, tip of the coronoid and olecranon process can be performed through this approach, as well as deepening the coronoid, olecranon and radial fossae; i.e. E2 and F2.10,11 However, if the range of movement obtained is still restricted, the lateral ligament complex may be completely released allowing subluxation of the joint5 (Figs 29.12, 29.13), i.e. E3/F3 – see above. At the end of the procedure the soft tissues are repaired, with the extensor origin and lateral ligament complex sutured down to bone using drill holes or suture anchors (Fig. 29.17). In the vast majority of cases the elbow will be stable at the end of the procedure allowing mobilization to be started in the immediate postoperative period.

Medial approach

A flap of brachialis/pronator teres is elevated giving access to the anterior capsule/joint, tip and medial edge of coronoid. Similarly, after decompression of the ulnar nerve, a posterior flap beneath triceps gives exposure to the posterior capsule and joint (Fig. 29.18). The posterior band of the medial collateral ligament can then also be released as necessary, exposing the medial edge of the humero-ulnar joint. The anterior band of the medial ligament and flexor origin are left intact to ensure stability. As a consequence articular surface pathology cannot be addressed through this approach.

Surgical techniques and rehabilitation

Early mobilization of the elbow after arthrolysis is almost universally recommended.13–16,18,21–23,26,28,29,31–33,34 Good quality pain control is, however, essential after surgery, otherwise active or passive elbow movement is too painful for effective mobilization to take place.13–15,18,21,23,26,27,31,44 Although the pain largely subsides within a few days, the elbow will then almost invariably be just as stiff, if not stiffer than before the operation.

Postoperative analgesia can be provided in a variety of ways, but relies on a team approach. The use of an axillary or supraclavicular continual brachial plexus block, via a thin indwelling catheter has revolutionized pain management after surgery. This has been shown to be very successful in providing effective pain relief for up to several days with the infusion titrated against the patient’s symptoms.13,15,18,21,23,26,31,44 A patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) system using opiates is also frequently used either primarily or as a secondary measure if the block fails.14,23,26,31,44

Apart from early motion, there is little agreement as to what constitutes optimal management after arthrolysis. A variety of different regimens have been recommended but there is relatively little evidence that one technique is superior to another.12–31 Continuous passive motion (CPM) can be useful in maintaining the improved range of movement obtained at surgery, particularly in the immediate postoperative period, as active movement may be impossible due to muscle weakness following a brachial plexus block. The aim is to prevent recurrence of the contractures – not to stretch and tear the remaining soft-tissues at the extremes of movement. No more movement can be obtained with the CPM than was achieved at surgery. There is little evidence that CPM provides additional value, although its usefulness may occur partly by reassuring patients after surgery that the operation was successful, as they can see that their arc of elbow movement is greater than that preoperatively.

Following discharge patients should be routinely encouraged to use their arm normally in the activities of daily living. The elbow can be mobilized safely within the limits of comfort, as pain and proprioception provide a feedback mechanism preventing inappropriate use. Post-arthrolysis, with the exception of interpositional arthroplasty,27,40 instability is uncommon,12–2931 even after extensive lateral release to allow subluxation (E3/F3), or even release of both collateral ligaments.43,45

The senior author has never used passive stretching techniques, based on a belief that it adds no value and may result in unnecessary pain. In a personal series of 70 patients after open arthrolysis,31 CPM was used for approximately 48 hours postoperatively to maintain as much of the movement achieved at operation as possible. No further treatment was used after discharge, and in particular no passive stretching. The average ROM improved by and was maintained at 40° 1 year after surgery (from 69° to 109°). The conclusion was that there appears to be little evidence to support passive stretching after arthrolysis, as the results31 were similar to series reporting the routine use of this technique.16,19,22,23,46

Static splints are frequently used to maintain the elbow in maximally flexed or extended positions, and can be used alternately during the rehabilitation period when resting, especially at night. In theory, the patient can then start to mobilize from the end of range position in the morning, although compliance may be an issue. Passive stretching techniques including manipulation by therapists or under anaesthesia,23 and using dynamic or patient-adjusted static turnbuckle splints19,22,46,47 remain controversial. These methods are based on a belief that stress relaxation of the soft tissues can be produced through plastic deformation. Advocates of these methods emphasize that the stretching should be ‘gentle’, i.e. very low forces applied within the limits of the patient’s symptoms. However, there must be considerable variation in the amount of force applied to the elbow in clinical practice, with the elbow often tolerating passive stretch poorly as detailed previously. In addition, elbow splints are uncomfortable as they tend to slip and require constant readjustment to allow them to act in the correct axis of rotation. If the splint is worn most of the time it will also interfere with daily activities, sleep and return to work. Gelinas et al48 recommended turnbuckle splinting for 20 out of 24 hours, although many of their patients could not cope with this rigorous regimen.

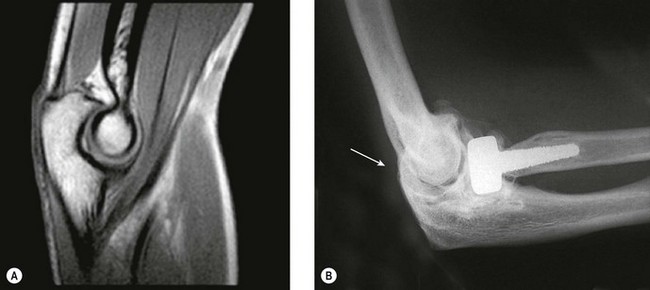

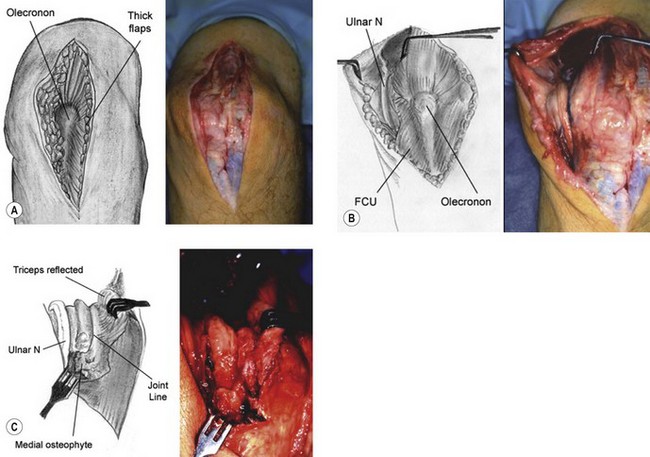

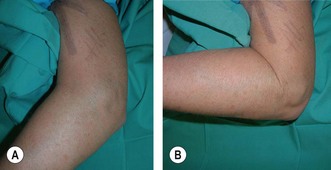

| 58-year-old women with elbow stiffness 6 months after missed displaced intra-articular distal humeral fracture |

Outcome and complications of treatment

Direct comparison between publications is difficult as the pathology and operative techniques, as well as methodology of reporting the results and complications, vary significantly. Outcomes from the recent literature are summarized in Table 29.1 and Box 29.3. Complications of open arthrolysis reported over the last 10 years range from 0 to 44% with an average of 15%.12–16,18–31 Although elbow movement improves in the vast majority of cases after open arthrolysis, some patients may be disappointed with the gain. Many series do not routinely report these cases as complications, while others state that a second release is sometimes necessary. Generally however, the results of revision surgery tend to be inferior.22,23

Box 29.3 Outcome after arthrolysis

Overall, ulnar neurapraxia/neuritis has emerged as the most common complication reported in the literature over the past decade.12–31 Symptoms and signs of ulnar neuropathy due to compression and/or fibrosis in the posttraumatic elbow are not uncommon and may be subtle. Medial pain and mild intrinsic weakness can be easily overlooked preoperatively and then exacerbated by the arthrolysis, especially if only a lateral approach has been used. The ulnar nerve is particularly vulnerable if flexion is improved significantly,19,21 as the cubital tunnel reduces in size as the retinaculum tightens with flexion. Other predisposing factors include subluxation of the nerve and callus formation, and in addition osteophytes or loose bodies can distort the floor of the tunnel. The nerve should then be decompressed, and indeed transposed if the bed is compromised. The latter, however, does not guarantee success due to perineural fibrosis.22 Prophylactic decompression/transposition is recommended by some surgeons if preoperative flexion is less than 120°.41

Finally instability has rarely been reported,27,40 partly as a good ROM can be obtained intraoperatively in the majority of patients without releasing the collateral ligaments. However, even if the lateral ligament complex/extensor origin is stripped from the distal humerus allowing elbow subluxation, only a few cases of instability have been reported – ‘it’s safe to sublux’.

1 Mansat P, Morrey BF. Semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for ankylosed and stiff elbows. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2000;82:1260-1268.

2 Throckmorton T, Zarkadas P, Sanchez-Sotelo J, et al. Failure patterns after linked semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty for posttraumatic arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2010;92:1432-1441.

3 Urbaniak JR, Hansen PE, Beissinger SF, et al. Correction of post-traumatic flexion contracture of the elbow by anterior capsulotomy. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1985;67:1160-1164.

4 Morrey BF. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: operative treatment including distraction arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1990;72:601-618.

5 Husband JB, Hastings H. The lateral approach for operative release of post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1990;72:1353-1358.

6 Gates HS, Sullivan FL, Urbaniak JR. Anterior capsulotomy and continuous passive motion in the treatment of post-traumatic flexion contracture of the elbow: a prospective study. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1992;74:1229-1234.

7 Amillo S. Arthrolysis in the relief of post-traumatic stiffness of the elbow. Int Orthop. 1992;16:188-190.

8 Boerboom AL, De Meyier HE, Verburg AD, et al. Arthrolysis for post-traumatic stiffness of the elbow. Int Orthop. 1993;17:346-349.

9 Modabber MR, Jupiter JB. Reconstruction for post-traumatic conditions of the elbow joint. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1995;77:431-446.

10 Cohen MS, Hastings H2nd. Post-traumatic contracture of the elbow: operative release using a lateral ligament sparing approach. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1998;80:805-812.

11 Mansat P, Morrey BF. The column procedure: a limited lateral approach for extrinsic contracture of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1998;80:1603-1615.

12 Wada T, Ishii S, Usui M, et al. The medial approach for operative release of post-traumatic contracture of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2000;82:68-73.

13 Olivier LC, Assenmacher S, Setareh E, et al. Grading of functional results of elbow joint arthrolysis after fracture treatment. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2000;120:562-569.

14 Bae DS, Waters PM. Surgical treatment of posttraumatic elbow contracture in adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:580-584.

15 Stans AA, Maritz NGJ, O’Driscoll SW, et al. Operative treatment of elbow contracture in patients twenty-one years of age or younger. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2002;84:382-387.

16 Marti RK, Kerkhoffs GMMJ, Maas M, et al. Progressive surgical release of a posttraumatic stiff – Elbow Technique and outcome after 2–18 years in 46 patients. Acta Orthop Scand. 2002;73(2):144-150.

17 Yamamoto K, Shishido T, Masaoka T, et al. Clinical results of arthrolysis using postero-lateral apprach for post-traumatic contracture of the elbow joint. Hand Surg. 2003;8:163-172.

18 Aldridge JM3rd, Atkins TA, Gunneson EE, Urbaniak JR. Anterior release of the elbow for extension loss. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2004;86:1955-1960.

19 Park MJ, Kim HG, Lee JY. Surgical treatment of post-traumatic stiffness of the elbow. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2004;86:1158-1162.

20 Gosling T, Blauth M, Lange T, et al. Outcome assessment after arthrolysis of the elbow. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:232-236.

21 Cikes A, Jolles BM, Farron A. Open elbow arthrolysis for posttraumatic elbow stiffness. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:405-409.

22 Ring D, Adey L, Zurakowski D, et al. Elbow capsulectomy for posttraumatic elbow stiffness. J Hand Surg (Am). 2006;31:1264-1271.

23 Tan V, Daluiski A, Simic P, et al. Outcome of open release for post-traumatic elbow stiffness. J Trauma. 2006;61:673-678.

24 Gausepohl T, Mader K, Pennig D. Mechanical distraction for the treatment of posttraumatic stiffness of the elbow in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2006;88:1011-1021.

25 Mader K, Koslowsky TC, Gausepohl T, et al. Mechanical distraction for the treatment of posttraumatic stiffness of the elbow in children and adolescents. Surgical technique. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 2007;89(suppl):26-35.

26 Sharma S, Rymaszewski LA. Open arthrolysis for post-traumatic stiffness of the elbow: results are durable over the medium term. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2007;89:778-781.

27 Brinsden MD, Carr AJ, Rees JL. Post-traumatic flexion contractures of the elbow: operative treatment via the limited lateral approach. J Orthop Surg Res. 2008;10(3):39.

28 Nolla J, David Ring D, Lozano-Calderon S, et al. Interposition arthroplasty of the elbow with hinged external fixation for post-traumatic arthritis. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2008;17(3):459-464.

29 Ruch DS, Shen J, Chloros GD, et al. Release of the medial collateral ligament to improve flexion in post-traumatic elbow stiffness. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2008;90:614-618.

30 Kulkarni GS, Kulkarni VS, Shyam AK, et al. Management of severe extra-articular contracture of the elbow by open arthrolysis and a monolateral hinged external fixator. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2010;92:92-97.

31 Higgs ZCJ, Danks BA, Sibinski M, et al. Elbow arthrolysis for post-traumatic stiffness. J Bone Joint Surg (Br) in press.

32 Kelly EW, Bryce R, Coghlan J, et al. Arthroscopic debridement without radial head excision of the osteoarthritic elbow. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:151-156.

33 Ball CM, Meunier M, Galatz LM, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of post-traumatic elbow contracture. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:624-629.

34 Kim SJ, Shin SJ. Arthroscopic treatment for limitation of motion of the elbow. Clin Orthop. 2000;375:140-148.

35 Araghi ADO, Celli A, Adams R, et al. The outcome of examination (manipulation) under anesthesia on the stiff elbow after surgical contracture release. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2010;19(2):202-208.

36 King GJ, Faber KJ. Posttraumatic elbow stiffness. Orthop Clin North Am. 2000;31:129-143.

37 Morrey BF, Askew LJ, Chao EY. A biomechanical study of normal functional elbow motion. J Bone Joint Surg (Am). 1981;63(6):872-877.

38 Morrey BF. The stiff elbow, Monograph 33. Am Acad Ortho Surg. 2006:23. Ch. 3

39 Armstrong AD, MacDermid JC, Chinchalkar S, Stevens RS, King GJ. Reliability of range-of-motion measurement in the elbow and forearm. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1988;7(6):573-580.

40 Cheng SL, Morrey BF. Treatment of the mobile, painful arthritic elbow by distraction interposition arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2000;82:233-238.

41 O’Driscoll SW. The stiff elbow, Monograph 33. Am Acad Ortho Surg. 2006:16-17. Ch 2

42 Hertel R, Pisan M, Lambert S, et al. Operative management of the stiff elbow: sequential arthrolysis based on a transhumeral approach. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:82-88.

43 Sojbjerg JO. The stiff elbow. Acta Orthop Scand. 1996;67:626-631.

44 Parikh RK, Rymaszewski LR, Scott NB. Prolonged postoperative analgesia for arthrolysis of the elbow joint. Brit J Anaesth. 1995;74:469-471.

45 Tsuge K, Murakami T, Yasunaga Y, Kanaujia RR. Arthroplasty of the elbow: twenty years’ experience of a new approach. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 1987;69:116-120.

46 Faber KJ, King GJ. Elbow contracture release: open operative strategies. In: Baker CLJ, Plancher KD, editors. Operative Treatment of Elbow Injuries. 1st ed. New York: Springer; 2002:285-294.

47 Morrey BF. The posttraumatic stiff elbow. Clin Orthop. 2005;431:26-35.

48 Gelinas JJ, Faber KJ, Patterson SD, et al. The effectiveness of turnbuckle splinting for elbow contractures. J Bone Joint Surg (Br). 2000;82:74-78.