Discontinuity of hemidiaphragm with focal defect (segmental diaphragmatic defect)

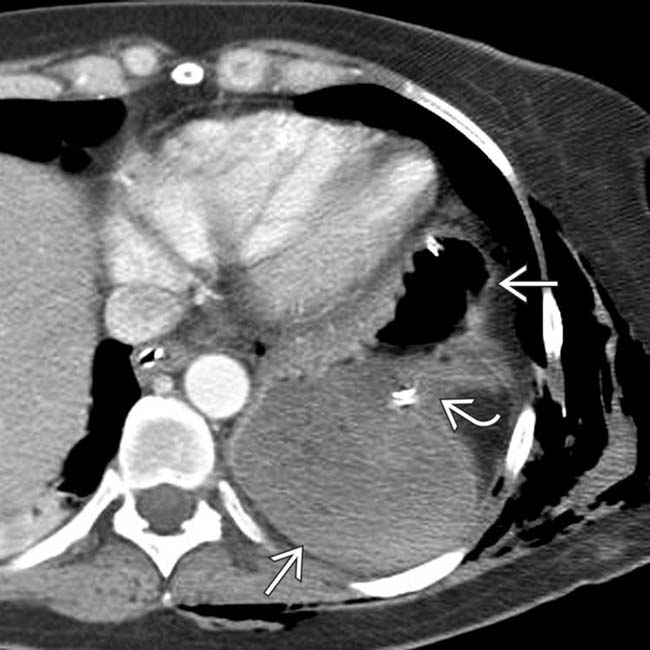

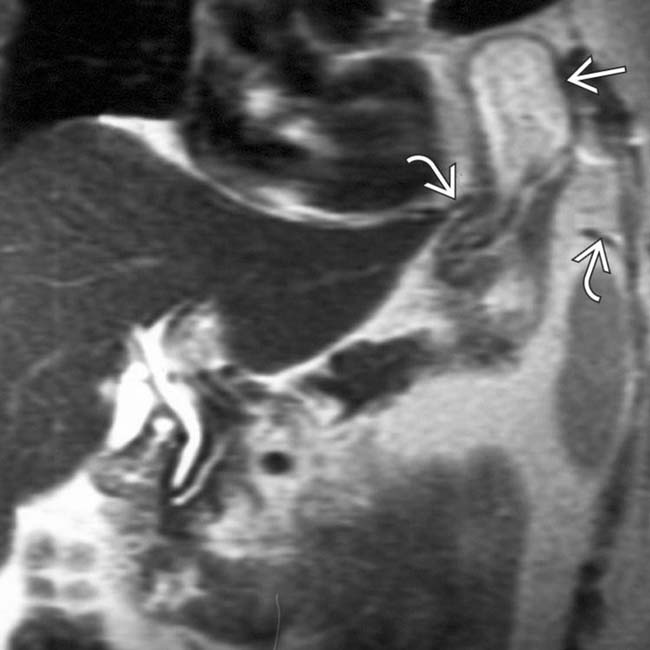

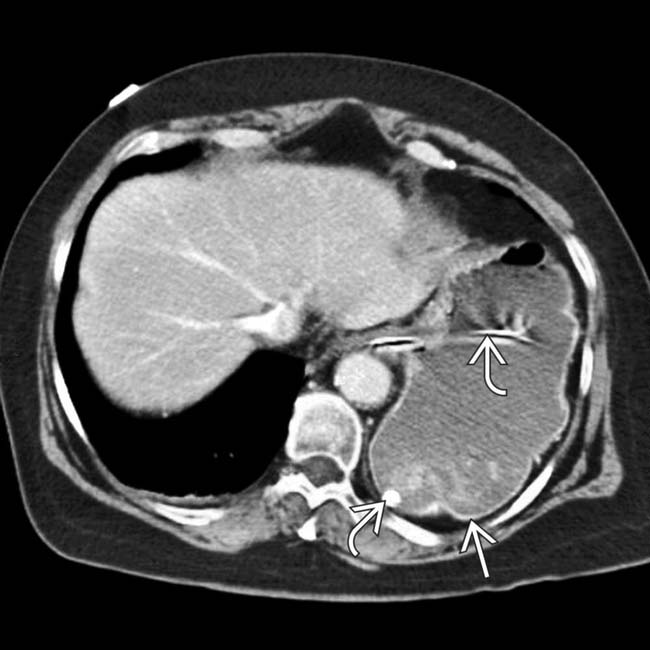

Dangling diaphragm sign: Free edge of torn diaphragm curls inward on axial images rather than continuing its normal course parallel to chest wall

Dangling diaphragm sign: Free edge of torn diaphragm curls inward on axial images rather than continuing its normal course parallel to chest wall Absent diaphragm sign: Absence of diaphragm in expected location without visualization of discrete tear

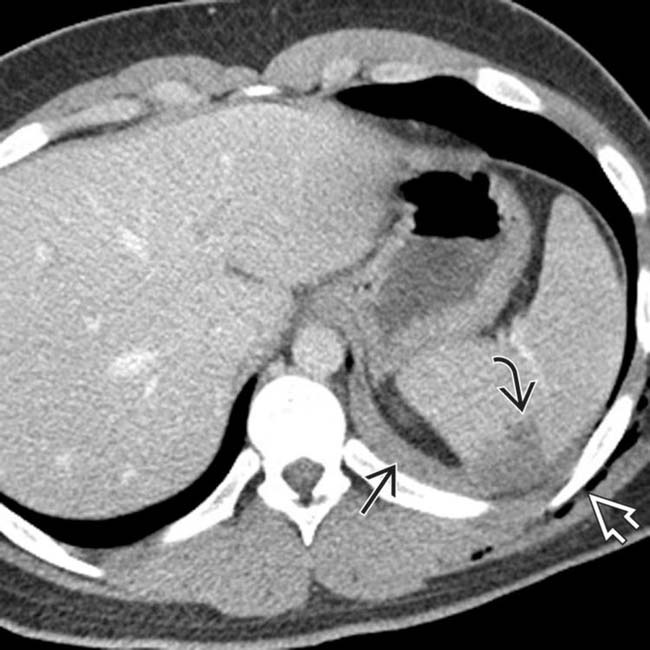

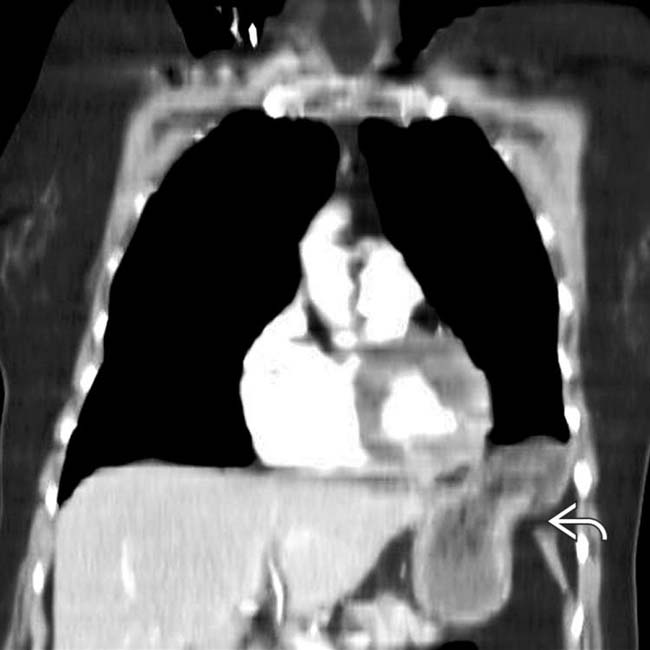

Absent diaphragm sign: Absence of diaphragm in expected location without visualization of discrete tear Fallen or dependent viscus sign: Herniated viscus abuts posterior ribs and thoracic wall without intervening lung

Fallen or dependent viscus sign: Herniated viscus abuts posterior ribs and thoracic wall without intervening lung Secondary signs of injury include simultaneous presence of pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum or hemothorax and hemoperitoneum, active extravasation of contrast in or near diaphragm, or injuries to organs lying near diaphragm

Secondary signs of injury include simultaneous presence of pneumothorax and pneumoperitoneum or hemothorax and hemoperitoneum, active extravasation of contrast in or near diaphragm, or injuries to organs lying near diaphragm

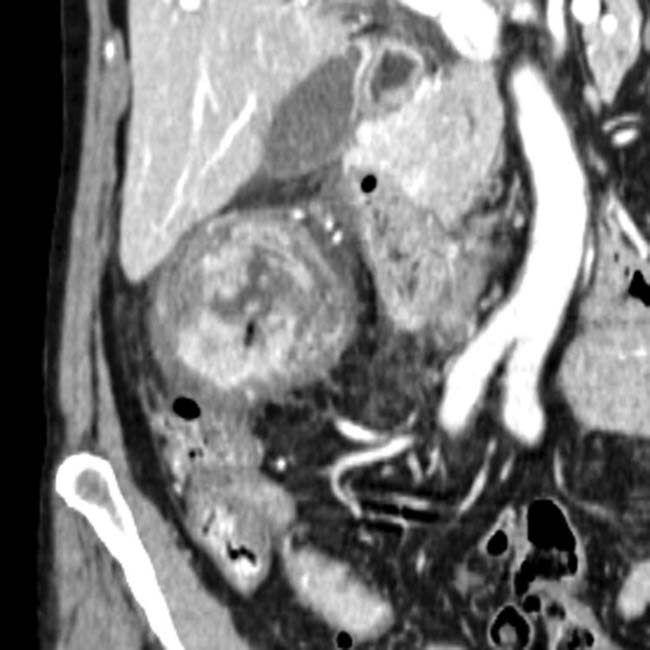

that is curved up toward the chest.

that is curved up toward the chest.

lies in the chest. Note that it has “fallen” medially and posteriorly to lie against the posteromedial chest wall. The stomach appears pinched

lies in the chest. Note that it has “fallen” medially and posteriorly to lie against the posteromedial chest wall. The stomach appears pinched  as it traverses the defect in the diaphragm (collar sign).

as it traverses the defect in the diaphragm (collar sign).

directly abuts the lung, and is not confined by the diaphragm.

directly abuts the lung, and is not confined by the diaphragm.

extending upward through a diaphragmatic defect.

extending upward through a diaphragmatic defect.IMAGING

General Features

CT Findings

• Multiple different direct and indirect signs of diaphragmatic injury, each with variable sensitivity and specificity

Discontinuity of hemidiaphragm with focal defect (segmental diaphragmatic defect)

Discontinuity of hemidiaphragm with focal defect (segmental diaphragmatic defect)

Dangling diaphragm sign: Free edge of torn diaphragm curls inward on axial images rather than continuing its normal course parallel to chest wall

Dangling diaphragm sign: Free edge of torn diaphragm curls inward on axial images rather than continuing its normal course parallel to chest wall

Absent diaphragm sign: Absence of diaphragm in expected location (without visualization of discrete tear)

Absent diaphragm sign: Absence of diaphragm in expected location (without visualization of discrete tear)

Fallen or dependent viscus sign: Herniated viscus abuts posterior ribs and thoracic wall without intervening lung

Fallen or dependent viscus sign: Herniated viscus abuts posterior ribs and thoracic wall without intervening lung

Discontinuity of hemidiaphragm with focal defect (segmental diaphragmatic defect)

Discontinuity of hemidiaphragm with focal defect (segmental diaphragmatic defect)

Dangling diaphragm sign: Free edge of torn diaphragm curls inward on axial images rather than continuing its normal course parallel to chest wall

Dangling diaphragm sign: Free edge of torn diaphragm curls inward on axial images rather than continuing its normal course parallel to chest wall Absent diaphragm sign: Absence of diaphragm in expected location (without visualization of discrete tear)

Absent diaphragm sign: Absence of diaphragm in expected location (without visualization of discrete tear) Fallen or dependent viscus sign: Herniated viscus abuts posterior ribs and thoracic wall without intervening lung

Fallen or dependent viscus sign: Herniated viscus abuts posterior ribs and thoracic wall without intervening lungRadiographic Findings

• Radiography

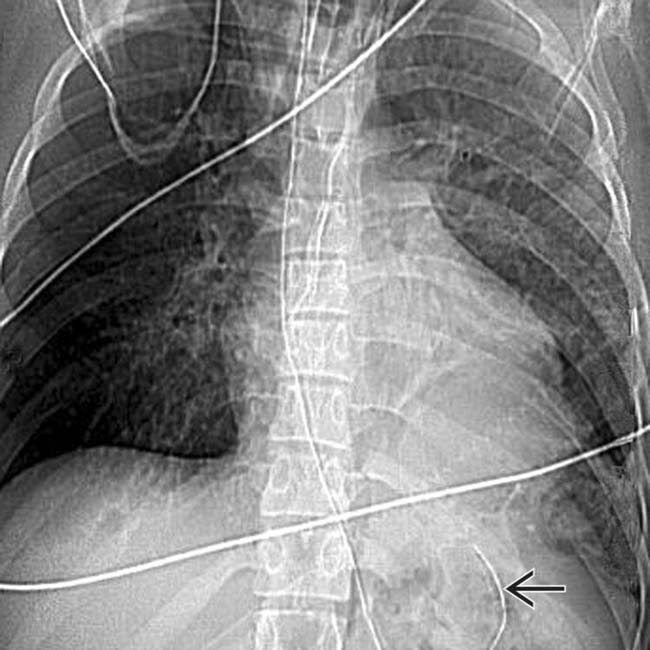

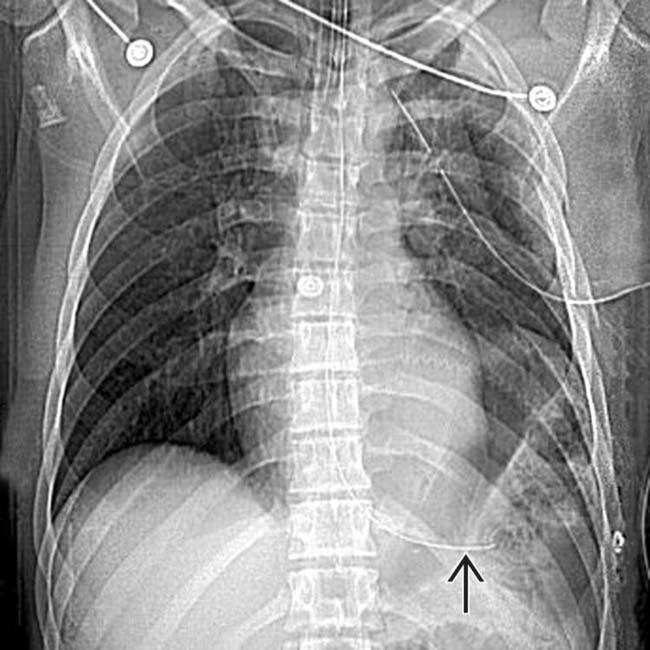

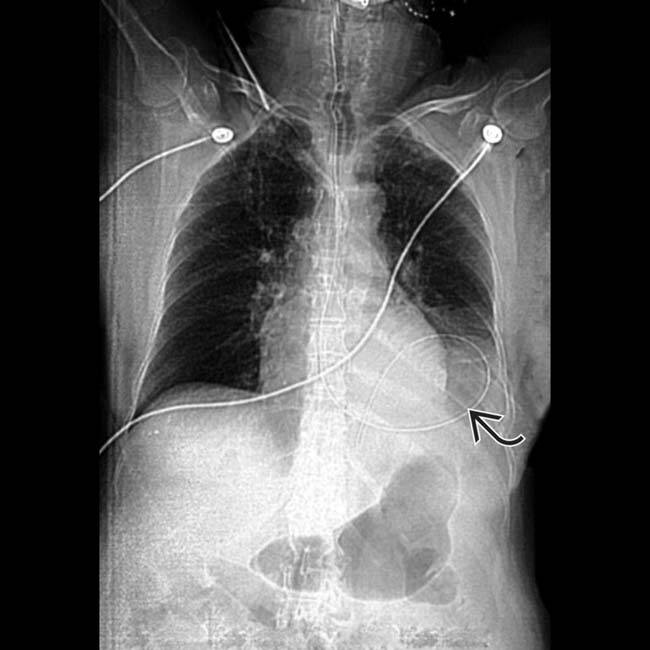

Radiographs are significantly less sensitive than CT for diaphragmatic injury, but may often be initial study performed

Radiographs are significantly less sensitive than CT for diaphragmatic injury, but may often be initial study performed

Radiographs are significantly less sensitive than CT for diaphragmatic injury, but may often be initial study performed

Radiographs are significantly less sensitive than CT for diaphragmatic injury, but may often be initial study performed

– Presence of lower thoracic soft tissue density mass or gas density suggesting herniated abdominal viscera

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernias (Bochdalek or Morgagni Hernias)

CLINICAL ISSUES

Presentation

Natural History & Prognosis

• Prognosis

Delayed diagnosis and repair: Poor prognosis

Delayed diagnosis and repair: Poor prognosis

Delayed diagnosis and repair: Poor prognosis

Delayed diagnosis and repair: Poor prognosis

– Initial diaphragmatic injury may be missed, even at surgery, due to attention to life-threatening injuries

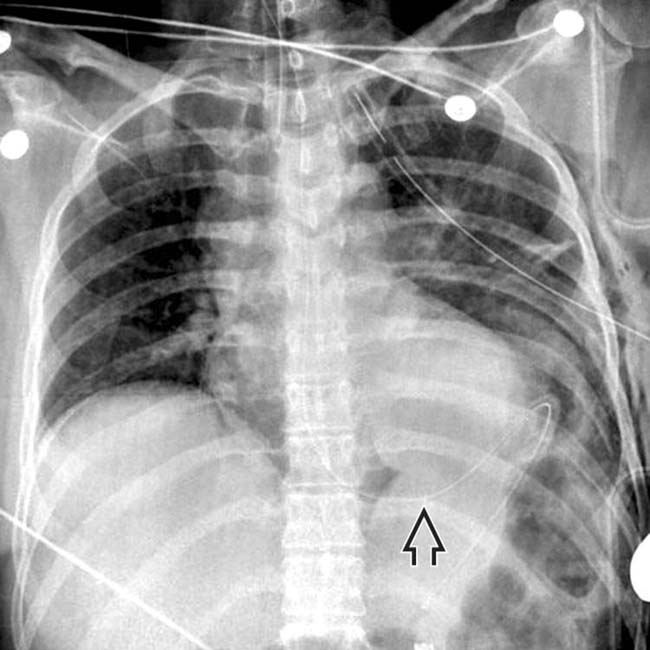

lying too far medial, posterior, and superior, indicating herniation through the diaphragm. This is the fallen viscus sign.

lying too far medial, posterior, and superior, indicating herniation through the diaphragm. This is the fallen viscus sign.

with hematoma, left hemothorax

with hematoma, left hemothorax  , and subcutaneous emphysema

, and subcutaneous emphysema  . The presence of hematoma above and below the left diaphragm was concerning for diaphragmatic injury, subsequently confirmed at surgery.

. The presence of hematoma above and below the left diaphragm was concerning for diaphragmatic injury, subsequently confirmed at surgery.

protruding into the thorax. Note the extensive enteric contrast material

protruding into the thorax. Note the extensive enteric contrast material  throughout the left thorax due to colonic perforation.

throughout the left thorax due to colonic perforation.

herniating into the chest. The diaphragm is identified as a low-signal curvilinear structure

herniating into the chest. The diaphragm is identified as a low-signal curvilinear structure  with a central gap.

with a central gap.

as it traverses a defect in the left diaphragm. Another sign of diaphragmatic rupture is the presence of abdominal fat

as it traverses a defect in the left diaphragm. Another sign of diaphragmatic rupture is the presence of abdominal fat  outside the confines of the diaphragm

outside the confines of the diaphragm  (therefore, in the thorax).

(therefore, in the thorax).

.

.

, indicating thoracic position.

, indicating thoracic position.

at the site of the tear.

at the site of the tear.

.

.

abutting the lung and pneumothorax.

abutting the lung and pneumothorax.

.

.

.

.

curled back up, indicating a high position of the stomach.

curled back up, indicating a high position of the stomach.

lying adjacent to the spine and posterior chest wall, instead of being suspended by the left hemidiaphragm. Note the NG tube

lying adjacent to the spine and posterior chest wall, instead of being suspended by the left hemidiaphragm. Note the NG tube  .

.