Chapter 540 Trauma to the Genitourinary Tract

Etiology

Injuries to the genitourinary tract in children usually result from blunt trauma during falls, athletic activities, or motor vehicle accidents (Chapter 66). Children are at greater risk of blunt renal injury than are adults, because they have less body fat and because the kidneys are not located directly behind the ribs. Children with a pre-existing renal anomaly such as hydronephrosis secondary to a ureteropelvic junction obstruction, horseshoe kidney, or renal ectopia also are at increased risk for renal injury. Blunt abdominal or flank trauma often causes a renal injury. Falling can cause a deceleration injury that results in an injury to the renal pedicle, interrupting blood flow to the kidney. If the bladder is full, blunt lower abdominal trauma can cause a bladder rupture. Rupture of the membranous urethra occurs in 5% of pelvic fractures. Straddle injuries usually are associated with trauma to the bulbous urethra.

Diagnosis

Evaluation of the patient begins after an adequate airway has been established and the patient is hemodynamically stable (Chapter 62). With significant abdominal injury, gross hematuria or >50 red blood cells (RBCs) per high-power field (HPF), or suspicion of renal injury (deceleration injury, flank pain or bruise), renal imaging is indicated. The bladder should be catheterized unless blood is dripping from the urethral meatus, which is an indication of potential urethral injury. Passing the catheter in the presence of a urethral injury can increase the extent of the damage and convert a partial membranous urethral tear into a total disruption. In these patients, a retrograde urethrogram should be performed by injecting radiopaque contrast medium into the urethral meatus under fluoroscopy. Oblique radiographs demonstrate the extent of the injury and whether urethral continuity is preserved or has been disrupted.

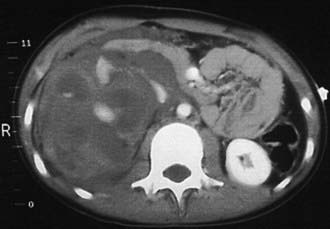

A 3-phase spiral CT scan should be performed to evaluate the kidneys, ureters, and bladder. The delayed images are important to detect renal extravasation of blood or urine. Prompt function of both kidneys without extravasation usually excludes significant renal injury. Renal injuries are classified according to the grading scale presented in Table 540-1. Minor renal injuries are most common; these include contusion of the renal parenchyma and shallow cortical lacerations not involving the collecting system. Major renal injuries include deep lacerations involving the collecting system, the shattered kidney, and renal pedicle injuries (Fig. 540-1). Complete absence of function of 1 kidney without contralateral compensatory hypertrophy (indicating congenital absence) should be regarded as an indication of major injury to the renal pedicle. Renal angiography, once used for further evaluation of renal injuries, particularly if a renal pedicle injury is suspected, now is rarely used because such patients are often hemodynamically unstable, and management is not significantly affected by the findings. In some cases, a pre-existing renal anomaly is demonstrated on the study. A ruptured ureteropelvic junction obstruction may be apparent if the kidney is intact but the distal ureter is not visualized.

| GRADE | DESCRIPTION |

|---|---|

| 1 | Renal contusion or subcapsular hematoma |

| 2 | Nonexpanding perirenal hematoma, <1 cm parenchymal laceration, no urinary extravasation; all renal fragments viable; confined to renal retroperitoneum |

| 3 | Nonexpanding perirenal hematoma, >1 cm parenchymal laceration, no urinary extravasation; renal fragments may be viable or devitalized |

| 4 |

Treatment

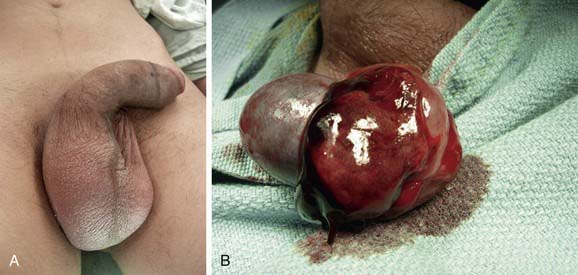

Testicular injuries are relatively uncommon in children because of the small size of the testes and their mobility within the scrotum. Such injuries usually result from blunt trauma during athletic activity. Typically, these boys have significant scrotal swelling, testicular pain, and tenderness (Fig. 540-2A). Ultrasonography demonstrates rupture of the tunica albuginea, which is the capsule of the testis, and surrounding hemorrhage. Prompt surgical treatment of testicular injuries increases the salvage rate (Fig. 540-2B).

Banks FC, Griffin SJ, Steinbrecher HA, et al. Aetiology and treatment of symptomatic idiopathic urethral strictures in children. J Pediatr Urol. 2009;5:215-218.

Cannon GM, Polsky EG, Smaldone MC, et al. Computerized tomography findings in pediatric renal trauma—indications for early intervention? J Urol. 2008;179:1529-1532.

Eassa W, El-Ghar MA, Jednak R, et al. Nonoperative management of grade 5 renal injury in children: does it have a place? Eur Urol. 2010;57(1):154-161.

Eeg KR, Khoury AE, Halachmi S, et al. Single center experience with application of the ALARA concept to serial imaging studies after blunt renal trauma in children—is ultrasound enough? J Urol. 2009;181:1834-1840.

Elder JS. Sports recommendations for children with solitary kidneys and other genitourinary abnormalities. In: Baskin L, Kogan BA, editors. Handbook of pediatric urology. ed 2. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005:271-277.

Fraser JD, Aguayo P, Ostlie DJ, et al. Review of the evidence on the management of blunt renal trauma in pediatric patients. Pediatr Surg Int. 2009;25:125-132.

Henderson CG, Sedberry-Ross S, Pickard R, et al. Management of high grade renal trauma: 20-year experience at a pediatric level I trauma center. J Urol. 2007;178:246-250.

Husmann D. Pediatric genitourinary trauma. In: Wein AJ, Kavoussi LR, Novick AC, et al, editors. Campbell-Walsh urology. ed 9. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2007:3929-3945.

Psooy K. Sports and the solitary kidney: how to counsel parents. Can J Urol. 2006;13:3120-3126.

Shenfeld OZ, Gdor J, Katz R, et al. Urethroplasty, by perineal approach, for bulbar and membranous urethral strictures in children and adolescents. Urology. 2008;71:430-433.

Tollefson MK, Ashley RA, Routh JC, et al. Traumatic obliterative urethral strictures in pediatric patients: failure of the cut to light technique at long-term followup. J Urol. 2007;178:1656-1658.

Umbreit EC, Routh JC, Husmann DA. Nonoperative management of nonvascular grade IV blunt renal trauma in children: meta-analysis and systematic review. Urology. 2009;74:579-582.