59 Trauma to the Brain

General Principles of Head Injury Care

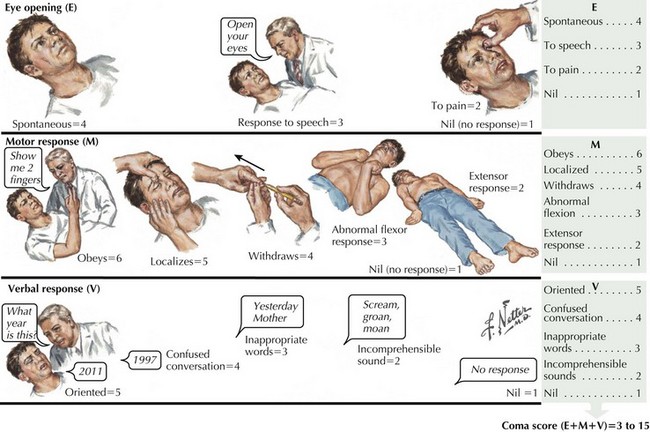

Concomitantly, the patient’s general level of responsiveness must be assessed using the Glasgow Coma Scale (Fig. 59-1). The lowest possible score of 3 means that individuals have no ability to open the eyes, no motor response to verbal command or direct stimuli, and no verbal response to the physician’s questions, giving a score of 1 or nil for each of the three components. The highest possible score is 15. Soft tissue injuries are commonly associated with more severe head injuries. A complete examination of the exterior surface of the face and head is vital. Blood loss can be extensive given the location of blood vessels within the dense connective tissue of the scalp, which decreases retraction of cut vessels and promotes bleeding.

Skull Fractures

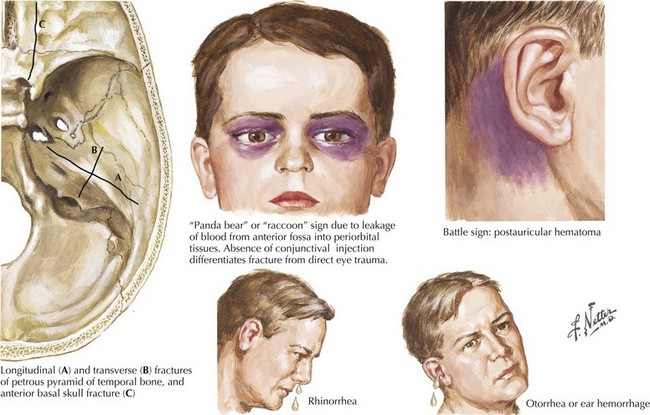

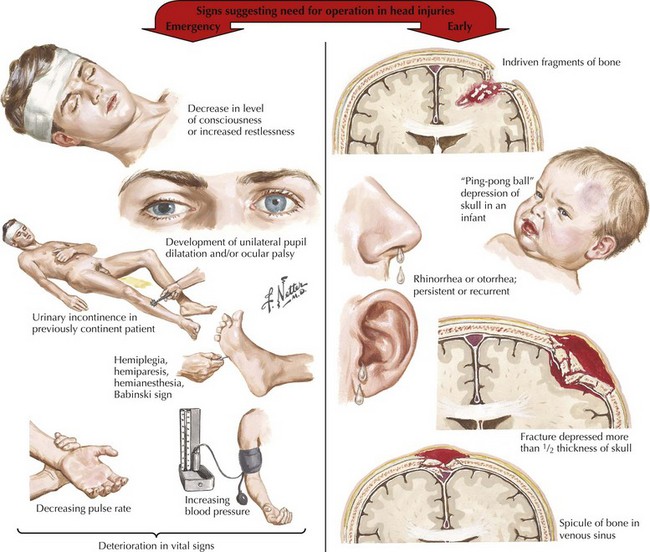

These can be located in the calvaria (vault) and/or the basal skull. Fractures of the cranial vault carry a 20 times greater incidence of intracranial hematoma in comatose patients and a 400 times greater incidence in conscious patients. Basal skull fractures, often difficult to identify on head CT, can present with pathognomonic signs, including raccoon or Panda bear eyes, battle signs (ecchymosis over the mastoid), and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) leakage from the nose, throat, or ears (Fig. 59-2). Most leaks resolve spontaneously. Persistent leaks necessitate operative treatment (Fig. 59-3).

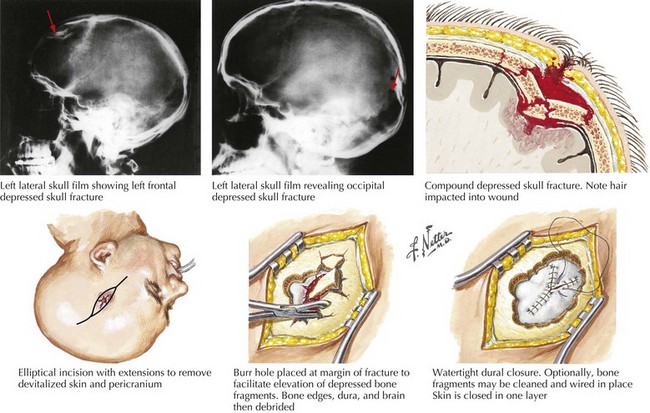

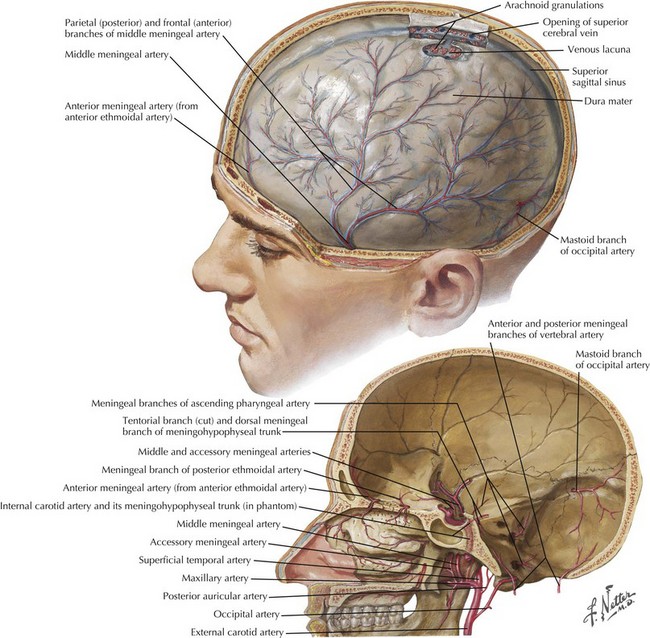

Depressed fractures, and those along the temporal bone, are more commonly associated with injury to the brain or blood vessels. A fracture line across the middle meningeal artery may predispose to an epidural hematoma. Open fractures with their communication between the intracranial vault and the external environment are associated with higher risks of spinal fluid leaks and infection (Fig. 59-4).

Extra-Axial Traumatic Brain Injuries

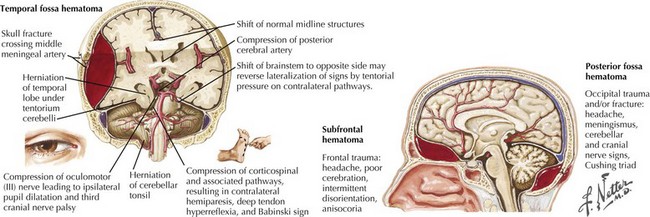

Epidural Hematomas

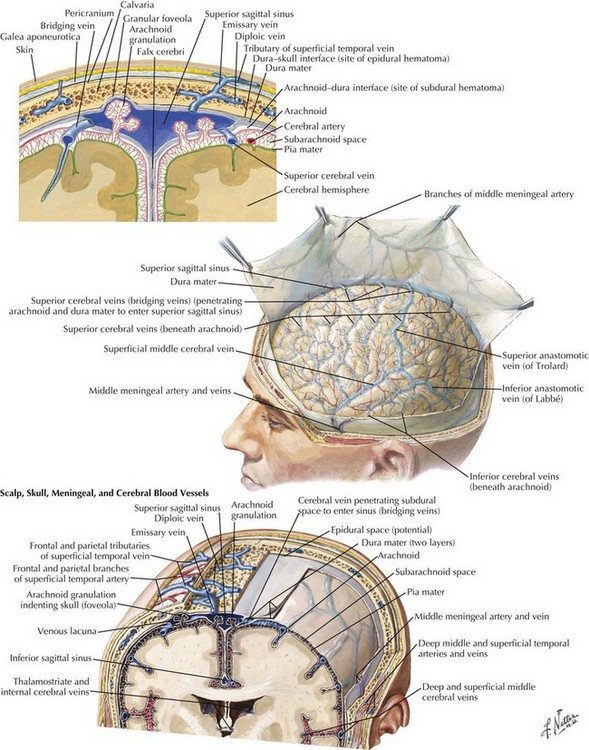

These represent an acute blood collection contained between the dura and inner table of the skull. These occur in approximately 2% of TBIs (Fig. 59-5). Epidural hematomas (EHs) most commonly develop in the temporal and parietal regions; 90% of EH are associated with a skull fracture. Arterial lacerations, particularly of the middle meningeal artery (Fig. 59-6) or, less commonly, venous injuries, initiate the formation of hematomas. Contiguous lacerations of the dura mater allow this blood into the epidural space.

Immediately after the closed head injury, the patient “typically” experiences an initial but relatively brief loss of consciousness secondary to the primary concussive injury. This is then followed by a lucid interval with return of wakefulness. Subsequently, as the torn vessels leak, an epidural hematoma develops and enlarges, leading to a rapid lapse into coma. Sometimes this entire process may transpire from injury, to transient loss of consciousness, and to a brief period of a “paradoxically reassuring alertness,” only to have a devastating, often irreversible, coma develop within just 1 hour after the blunt head injury (see Fig. 59-3). However, this classic presentation occurs in less than one third of affected individuals. The actual rate of symptom progression depends on the type of associated brain injuries, their etiology, and the subsequent precise rate of blood accumulation within the epidural space.

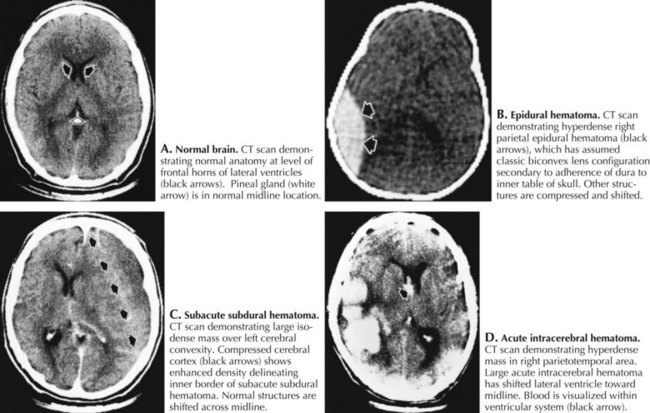

Cranial CT imaging usually demonstrates a hyperdense, biconvex collection between the skull and brain (Fig. 59-7). On occasion, the initial CT is normal as the hematoma has yet to develop to a size that is definable. Thus when the patient is “at risk,” it is essential to be prepared to repeat the CT scan at the slightest change in clinical status. Once the EH is identified, emergency surgical evacuation is indicated. Any failure to recognize an epidural hematoma has a most significant mortality depending on patient age, time of treatment, hematoma size, and associated injuries.

Acute Subdural Hematoma

These blood collections are located between the brain parenchyma and the dural membranes and are classified by their temporal profile. Acute subdural hematomas (SDHs) occur in 15% of TBI patients; these are seven to eight times more common than epidural hematomas. Older individuals are at greater risk because as the brain ages, there is an innate atrophy of the cerebral cortex. Thus in seniors, as the brain “normally” lessens in volume, an increasing space develops within their subdural compartment. In turn this leads to increased stretch on the bridging veins between the skull and the cerebral surface (Fig. 59-8). When any individual sustains direct head trauma, the brain parenchyma accelerates and decelerates in relation to fixed dural structures. This leads to a tearing of the now anatomically stretched veins that form a “bridge” between the cerebral cortex and the skull. Similarly concomitant injury to cortical arteries can also lead to bleeding into the subdural space (Fig. 59-9).

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The initial severity of the injury determines the patient’s clinical presentation; this varies from neurologically intact, to altered mental states, subsequently associated with pupillary inequality and motor weakness, and eventually becoming comatose with signs of decorticate or decerebrate posturing. The lucid interval, a classical finding with epidural hematoma, is also commonly seen with acute SDH. Brain CT is the initial test of choice for detecting SDH and concomitant brain injuries. An acute SDH is recognized by its hyperdense crescent-shaped image between the brain and skull (see Fig. 59-7). Unlike epidural hematomas, SDHs typically cross skull suture lines, and sometimes extend along the falx cerebri. Head CT sometimes underestimates the size of the SDH given the similar imaging density of the nearby bone.

Treatment and Prognosis

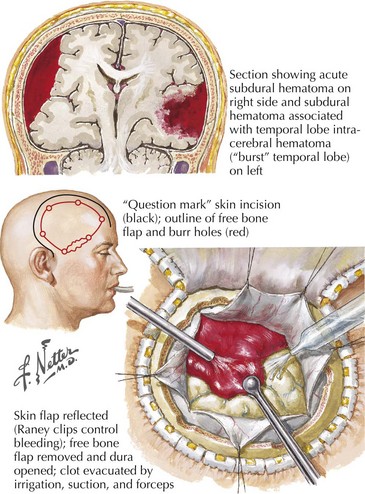

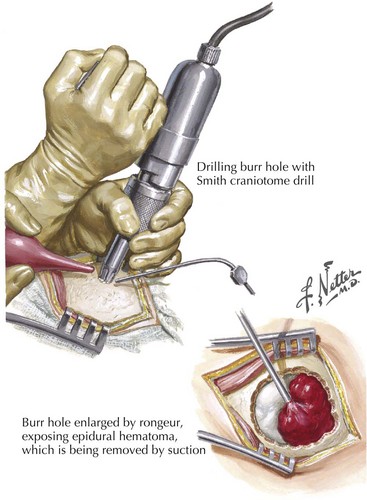

If the patient has mental status changes or signs of focal cerebral compromise, beginning treatment of acute SDH as rapidly as possible with medical management for increased ICP and the associated cerebral edema using mannitol is very useful. Surgical intervention with a craniotomy is appropriate for individuals whose SDHs have mass effect, leading to focal neurologic deficits. Once a significant SDH is defined, surgical evacuation of the clot must be expeditiously performed. A burr-hole trephine evacuation is inadequate because the clot is often already more viscous than normal blood. Increased postoperative ICP occurs in almost 50% of SDH patients, and thus the initial medical management must be continued (Fig. 59-10). Residual and recurrent hematomas are also postoperative concerns.

Clinical Presentation and Diagnosis

The presentation may range from subtle focal signs of cerebral compromise as determined by the site of injury such as aphasia, focal weakness or sensory loss, confusion, or seeming early dementia with bifrontal lesions, to those symptoms of the various herniation syndromes. A high clinical suspicion of SDH must always occur especially with the at-risk individual whenever there is remote history of head trauma. CT is the study of choice (see Fig. 59-7). Occasionally, a brain MRI serendipitously leads to a diagnosis of SDH in patients presenting with stroke-like or seizure-type symptoms.

Intra-Axial Traumatic Injuries

Intraparenchymal Hematomas

About a quarter of head injury patients develop intraparenchymal hematomas: these are well demarcated areas of acute hemorrhage. The basic pathophysiology is similar to contusions. Most (90%) occur within the frontal and temporal lobes. Shear injury leads to deep cerebral white matter hematomas. Two thirds of intraparenchymal hematomas are also associated with concomitant subdural or epidural hematomas (see Fig. 59-9). An intraventricular hemorrhage, often complicated by hydrocephalus, may also commonly develop.

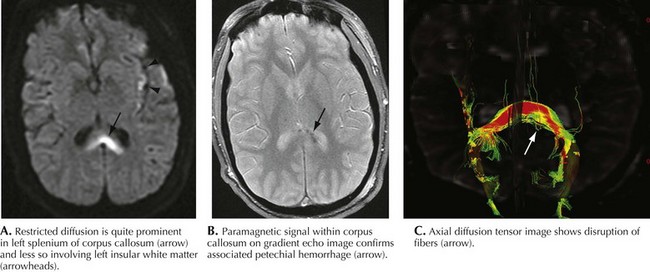

Diffuse Axonal Shear Injury

The combination of rotational acceleration and deceleration of the brain during traumatic impact results in shearing of both diffuse axonal pathways and small capillaries. High-speed motor vehicle accidents are the most common etiology in the civilian population. Very microscopic, penetrating blood vessels are damaged at multiple levels including the corticomedullary junction, corpus callosum, internal capsule, deep gray matter, and upper brainstem, leading to numerous small hemorrhagic foci. Early on, conventional CT scanning will not demonstrate any abnormality related to this type of lesion. The micro-hemorrhages may be best seen on gradient echoT2-weighted sequences (Fig. 59-11). Later there may be nonspecific white matter hyperintense lesions with atrophic changes. Shear injury is very commonly associated with other intraaxial and extraaxial traumatic insults, including focal hematomas. Shear injury is a major prognostic contributor to overall head injury morbidity.

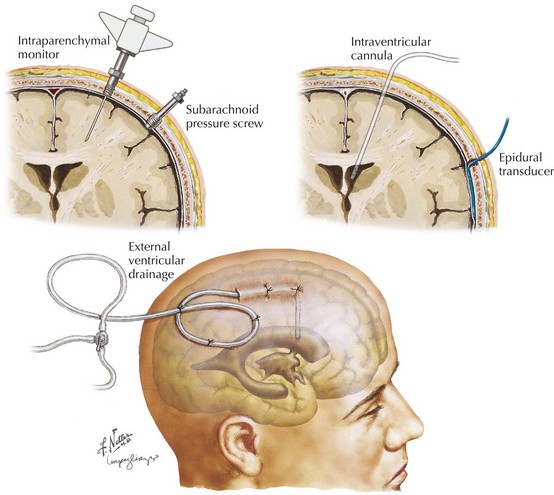

Patients with diffuse axonal injury often develop cerebral edema, with resulting increased ICP. Pressure monitors are required in patients whose clinical examination results are not reliable. Intraparenchymal monitors are usually used because the ventricles are often so compressed that ventricular catheter placement is difficult (see Fig. 59-11).

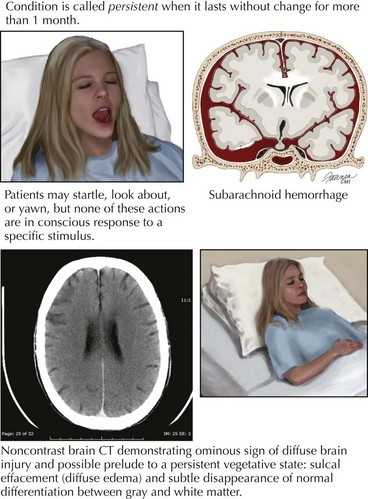

It is this group of patients who may remain comatose for extended periods. This clinical picture is classified as a persistent vegetative state (Chapter 16). This entity carries an extremely poor prognosis (Fig. 59-12).

Posterior Fossa Lesions

Cerebellar and posterior fossa traumatic brain lesions account for only 5% of post-TBI sequelae. Epidural hematomas, SDH, and intracerebellar hematomas are the most common traumatic lesions at this level. Because of the limited space within the posterior fossa, strategically placed lesions at this level can rapidly lead to early neurologic decline secondary to both brainstem compression and acute hydrocephalus. Careful assessment of patients for these injuries is critical, especially in high-risk individuals with basal skull fractures. MRI is the study of choice for detecting posterior fossa damage. Normal bony architecture, as imaged with brain CT, frequently prevents identification of posterior fossa lesions artifacts in patients with TBI. Therefore, evacuation of the hematoma with posterior fossa craniectomy is the primary treatment modality when there is a critical mass lesion (Fig. 59-13). In contrast, a ventricular drain is adequate for intraventricular bleeds.

Overall Treatment Protocols

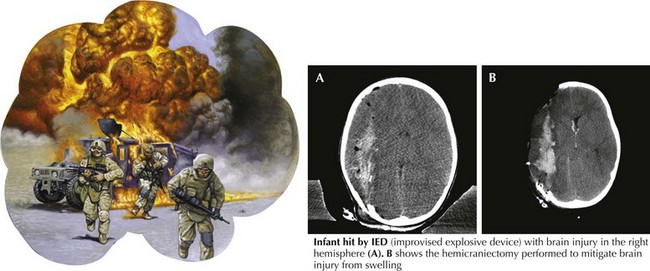

Recent military experience has led to a more aggressive surgical approach in handling brain trauma. Because two surgeons were often working together in a highly efficient and staffed operating theater environment, in many cases receiving severe head trauma within minutes of the injury, even the soldier with a low GCS score underwent aggressive cranial decompression to help manage brain edema (Fig. 59-14). This minimizes the need for intensive ICP medical management in these initial combat hospital facilities. It will take time and long-term follow-up to eventually evaluate the prognosis for useful brain recovery with such aggressive and bolder therapeutic approaches.

Aarabi B. Surgical Outcome in 435 Patients who sustained missile head wounds during the Iran-Iraq War. Neurosurgery. 1990;27:692-695.

Aarabi B, Taghipour M, Alibaii E, et al. Central Nervous System Infections after Military Missile Head Wounds. Neurosurgery. 1998;42:500-509.

Brain Trauma Foundation, American Association of Neurological Surgeons, Joint Section on Neurotrauma and Critical Care.

Chesnut RM. Management of brain and spine injuries. Crit Care Clin. 2004;20:25-55.

Fakhry SM, Trask AL, Waller MA, et al. Management of brain-injured patients by an evidence-based medicine protocol improves outcomes and decreases hospital charges. J Trauma. 2004;56:492-500.

Faul M, Wald MM, Rutland-Brown W, et al. Using a cost-benefit analysis to estimate outcomes of a clinical treatment guideline: testing the Brain Trauma Foundation guidelines for the treatment of severe traumatic brain injury. J Trauma. 2007 Dec;63(6):1271-1278.

Guidelines for Field Management of combat-related head trauma, Brain Trauma Foundation, New York, NY, 2005.

2007 Guidelines for the management of severe traumatic brain injury. Brain Trauma Foundation; American Association of Neurological Surgeons; Congress of Neurological Surgeons. J Neurotrauma. 2007;24(Suppl. 1)):S1-106. A detailed overview

Personal communication, Brett Schlifka, MD, Maj, USA, 2006.

Riechers GR, Ramage A, Brown W, et al. Physician knowledge of the Glasgow Coma Scale. J Neurotrauma. 2005;22(11):1327-1334.