CHAPTER 77 TRAUMA IN PREGNANCY

The pregnant trauma patient presents significant challenges to the trauma surgeon. The physiologic changes in the mother during pregnancy represent both diagnostic and treatment dilemmas, while the need to treat two patients simultaneously may represent both clinical and emotional challenges for the trauma team.

INCIDENCE

Trauma complicates 7%–8% of pregnancies and is the leading cause of maternal death.1 The incidence of significant maternal and fetal injury increases with gestational age, with slightly over 50% of injuries occurring in the third trimester.2

The most common mechanisms of injury for maternal trauma are motor vehicle collisions (MVCs) at 55%–70%, followed by assault at 12%–22%. In contrast, fetal death is a consequence of motor vehicle collisions in 82% of cases, followed by gunshot wounds (GSWs) in 6%, and falls in 3%.3

MECHANISM OF INJURY

Blunt Trauma

Blunt trauma is the leading cause of both maternal and fetal death and is usually a consequence of MVCs, assaults, or falls. Although mortality rates are similar for pregnant versus nonpregnant blunt trauma patients, with equivalent Injury Severity Scores (ISS), their patterns of injury are notably different. Pregnant patients injured in MVCs are more likely to sustain significant abdominal injuries and less likely to sustain head injuries than their nonpregnant counterparts. Splenic, hepatic, and retroperitoneal injuries occur more frequently in gravid trauma patients, due in part to the increased vascularity associated with pregnancy as well as to the displacement of the abdominal contents by the uterus. Up to 25% of pregnant blunt trauma patients sustain significant splenic or hepatic lacerations.4

Direct injury to the fetus from blunt trauma is rare (<1%). The leading cause of fetal mortality after blunt trauma is maternal mortality followed by placental abruption. Since the uterus is elastic and the placenta is not, sheering forces can result in placental abruption, even in otherwise minor blunt abdominal trauma. The estimated incidence of abruption is 2%–3% for minor trauma and up to 40% for severe blunt abdominal trauma. Uterine rupture occurs less commonly than placental abruption but increases in incidence with gestational age.3 Although uterine rupture is life-threatening to both the mother and the fetus, its diagnosis is often difficult, given the variable and sometimes subtle clinical presentation. The clinician must maintain a high index of suspicion for both placental abruption and uterine rupture in any patient with blunt abdominal trauma, especially in late gestation.

Penetrating Trauma

Penetrating trauma is usually the result of either GSWs or stabbing. This type of injury in pregnant patients is most often sustained at the hands of a spouse or intimate partner. Death rates for these injuries are actually decreased in pregnant patients compared with nonpregnant patients, owing to the protective effect for the mother of the gravid uterus. Unfortunately, the consequence to the fetus is a mortality rate of 71% for abdominal GSWs and 42% for abdominal stab wounds. It should also be noted that due to the upward displacement of intra-abdominal content by the uterus in pregnancy, upper quadrant abdominal stab wounds carry a high risk for small bowel injury in pregnant patients.1,3

Intimate Partner Violence

Intimate partner violence (IPV) is not uncommon in pregnancy. Between 7.4% and 21% of pregnant patients reported physical abuse at the hands of an intimate partner and fully two-thirds reported an escalation of violence during pregnancy. Physically abused women have higher rates of miscarriage and low birth-weight infants than nonabused women. Battering during pregnancy is not only associated with an increase in the frequency of abuse but also with a threefold increase in risk of homicide compared with physically abused women who are not pregnant.5 Hence, intrapartum battering is a marker for a particularly violent and potentially lethal relationship.

PHYSIOLOGIC ALTERATIONS OF PREGNANCY

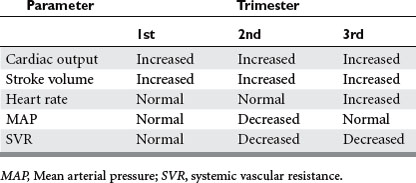

Increased levels of estrogen and progesterone, as well as of renin and aldosterone, lead to increased sodium resorption and plasma volume expansion beginning at about 10 weeks gestation. While heart rate, mean arterial pressure, and central venous pressure are not yet altered, the cardiac output may start to increase by 1–1.5 l/min (Table 1). Progesterone also promotes hypertrophy of the kidneys from 10 weeks gestation and leads to impaired gallbladder contraction and bile stasis. Beginning at the end of the first trimester, there may be an increase in gallstone formation.

Second Trimester

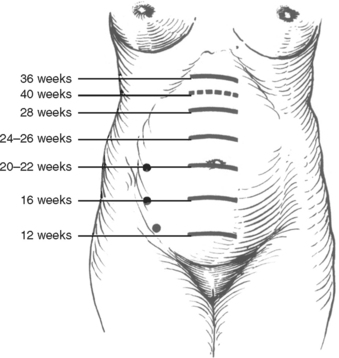

During the second trimester, the uterus begins to rise out of the pelvis, and by 20 weeks, it may reach the umbilicus (Figure 1). Blood pressure falls by about 5–15 mm Hg and reaches its lowest level of the pregnancy. In traumatic maternal hemorrhage, placental blood flow is preferentially reduced, and 30% of maternal blood volume may be lost prior to signs of shock.6 The “supine hypotensive syndrome” is caused by compression of the inferior vena cava by the gravid uterus, decreasing venous blood return and thereby decreasing preload and cardiac output. Turning the mother left side down increases cardiac output by about 30% after 20 weeks gestation.7

Third Trimester

During the third trimester, blood pressure returns to more normal levels and heart rate increases up to 20 beats per minute relative to the nonpregnant state. This physiologic tachycardia must be considered when evaluating the pregnant trauma patient. Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure and left ventricular function remain normal, while systemic and pulmonary vascular resistances are decreased.8

After 30 weeks gestation, plasma volume has increased 40%, accompanied by a 15% increase in red blood cell mass. This discrepancy leads to the “physiologic anemia of pregnancy.”9 Serum albumin declines by up to 30% because of this volume expansion. Benign physiologic pericardial effusion is more prevalent and may complicate the Focused Assessment with Sonography for Trauma (FAST). The decrease in colloid oncotic pressure may increase the risk for pulmonary edema. A hypercoagulable state is also induced because of an increase in nearly all coagulation factors, procoagulants and fibrinogen, and a reduction in fibrinolytic activity.10

Anatomic changes in the thorax include the diaphragm rising about 4 cm and the chest diameter increasing by 2 cm.11 The most significant changes in respiratory function include an increase in minute ventilation by as much as 50%, mostly by an increase in tidal volume. Functional residual capacity decreases largely due to elevation of the diaphragm. A state of compensated respiratory alkalosis results in a chronic reduced PaCO2 to approximately 30 mm Hg and reduced plasma bicarbonate level.12

Uterine compression of the bladder and ureters results in a compensated hydronephrosis. The increase in blood volume and cardiac output is associated with increased renal blood flow of up to 80% and increased glomerular filtration rate of 50%. Blood urea nitrogen and serum creatinine are commonly reduced, but urine output volume does not significantly change.

DIAGNOSIS

Secondary Survey

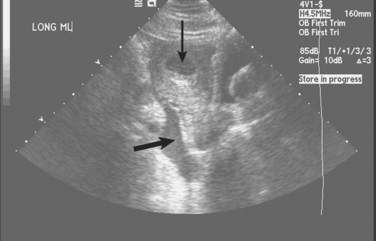

The physical examination of the abdomen is difficult in pregnancy due to displacement of abdominal contents from their normal position. Additionally, stretching of the abdominal wall by the uterus in late pregnancy may result in a relative insensitivity to peritoneal irritation, resulting in difficulty in detecting peritonitis on clinical examination alone. The FAST examination represents a rapid and noninvasive means of evaluating the patient for the presence of intra-abdominal fluid. The sensitivity of the FAST examination in pregnant patients, at 83%, is slightly lower than in the nonpregnant population,; however, the specificity is similar at 96%.13 Although it does not replace formal fetal ultrasonography, the FAST examination may be used to get a rapid picture of the fetal status during the initial resuscitation by detecting the fetal heart rate. The FAST has also been reported to detect unsuspected pregnancies in some trauma patients, thus influencing subsequent management.14 The use of ultrasonography does not involve ionizing radiation and poses no known risk to the developing fetus.

Initial Evaluation of the Fetus

Cardiotrophic monitoring is the mainstay of fetal assessment in the third trimester. The practice management guidelines of the Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma (EAST) include a recommendation that all pregnancies greater than 20 weeks gestation should undergo fetal monitoring for a minimum of 6 hours.15 More prolonged monitoring has been recommended in cases of uterine contractions, abnormal fetal heart rate patterns, and in cases of severe maternal trauma.3 Fetal monitoring is used to evaluate both the state of the fetus as well as the presence and frequency of uterine contractions. It is the single most reliable tool available for the assessment of placental abruption. The use of fetal monitoring routinely, even in cases of apparently minor maternal trauma, must be emphasized. A recent multi-institutional study of 13 Level I and Level II trauma centers revealed that fetal monitoring was obtained on only 61% of trauma patients with third trimester pregnancies.16

Exposure to Radiation from Diagnostic Radiographs

Predicting teratogenicity as a consequence of fetal radiation exposure is difficult; however, no study has shown an increase above baseline for exposures of 10 rad (100 mGy).15 According to the recommendations on radiation exposure during pregnancy made by the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG), exposure of 5 rad (50 mGy) is not associated with any increase in risk of fetal loss or of birth defects.17 Other than teratogenicity, the principal concern in exposing a fetus to radiation is that of increasing the risk of childhood cancers. The National Radiation Protection Board of Britain cites a 6% excess risk per 100 rad exposure.18

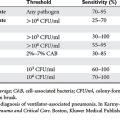

Most of the common radiographic tests employed in the evaluation of trauma patients are associated with fetal radiation doses of 1/100 rad or less (Table 2). The exception to this is the abdominal CT, with a radiation dose of 2.60 rad for 10-mm slices. This is still only about half of the 5-rad dose cited by ACOG as safe. However, it should be kept in mind that the newer multiplanar scanners may have a higher radiation exposure. Consultation with the radiology department is strongly recommended in planning a diagnostic workup that will minimize the risk of radiation exposure.

| Procedure | Approximate Fetal Dosea (rad) |

|---|---|

| Plain Films | |

| Chest (two views) | 0.00002–0.00007 |

| Abdomen | 0.1 |

| Cervical spine | 0.002 |

| Pelvis | 0.040 |

| Thoracolumbar spine | 0.370 |

| CT Scansb | |

| Head CT | <0.05 |

| Chest CT | <0.100 |

| Abdominal CT | 2.60 |

a Dose varies depending on exact procedure used and on body habits.

b Estimate based on 10-mm slices.

Adapted from Barraco RD, Chiu WC, Clancy, et al: Practice management guidelines for the diagnosis and management of injury in the pregnant patient: the EAST practice management guidelines work group, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma World Wide Web site, http://www.east.org/tpg/pregnancy.pdf; and Wakeford R, Little MP: Risk coefficients for childhood cancer after intrauterine irradiation: a review. Int J Rad Biol 79(5):293–299, 2003.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Blunt Trauma

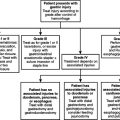

Uterine rupture occurs in only 0.6% of instances of blunt trauma during pregnancy.19 Direct fetal injury is also very rare and complicates <1% of cases. As it is in the nonpregnant patient, nonoperative management of abdominal solid organ injuries should be the treatment of choice in hemodynamically stable pregnant patients. The greatest difference in nonoperative management of abdominal injuries is that angiographic therapeutic adjuncts are not advisable because of the potential for large radiation exposure. In unstable patients, operative management may best limit maternal and fetal shock, and the indications for laparotomy are similar to those in nonpregnant patients. Hemodynamic instability in patients with blunt abdominal trauma and free intraperitoneal fluid found by ultrasonography are indications for urgent laparotomy (Figure 2). At laparotomy, the uterus should be left intact unless there is direct uterine injury.

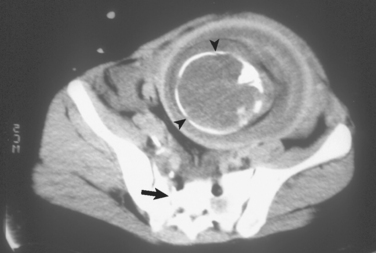

Pelvic fractures have several serious implications in the pregnant patient and may be associated with fetal demise in up to 25% of cases. Engorgement of pelvic and retroperitoneal vasculature renders any pelvic fracture at increased risk for significant hemorrhage. Fetal injury or death may result from direct placental injury or from maternal shock (Figure 3). Pelvic angiography for embolization should be an adjunct used for life-threatening pelvic hemorrhage, as the radiation required for the procedure exceeds safe levels for the fetus.

Penetrating Trauma

The use of CT scanning in penetrating torso trauma in the pregnant patient is an area that has not yet been well studied. In blunt trauma, the judicious use of abdominopelvic CT scanning to evaluate for abdominal injury is recommended. In penetrating trauma, the benefits and risks of the options must be considered. In penetrating torso trauma in nonpregnant patients, triple contrast abdominopelvic CT reliably excludes peritoneal penetration to prevent unnecessary laparotomy.20 The risks of CT scanning include the fetal exposure to ionizing radiation. The risks of general anesthesia and unnecessary laparotomy must be considered in balance. Without clear evidence and recommendations on the utility of CT in penetrating torso trauma, careful individual decision making and judgment are required between immediate laparotomy and diagnostic CT scanning.

Cesarean Section

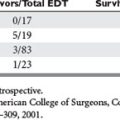

While the importance of emergency cesarean section for fetal salvage is evident, the indications for perimortem cesarean section remain controversial (Table 3). Morris et al. showed that emergency cesarean section for patients at greater than 25 weeks gestation was associated with a 45% fetal survival and that 60% of infant deaths resulted from delay in recognition of fetal distress.21 In this multicenter study, infant survival was independent of maternal injury, and no fetus delivered without fetal heart tones survived.

Table 3 Indications for Emergency and Perimortem Cesarean Section

Perimortem cesarean section refers to those cases of emergency cesarean section performed surrounding maternal death, whether fetal delivery is performed prior to or after actual maternal death, and should be considered in any moribund pregnant patient of at least 24 weeks gestational age if fetal heart tones are still present.15 When performed following maternal death, fetal neurological outcome and survival are closely dependent upon the time interval between maternal death and fetal delivery. Fetal delivery must occur within 20 minutes of maternal death, but should ideally start within 4 minutes of maternal cardiac arrest. The anticipated fetal survival rate is up to 70% when delivery is performed within 5 minutes of maternal death.

MORBIDITY AND COMPLICATIONS MANAGEMENT

Fetomaternal Hemorrhage

Fetomaternal hemorrhage occurs in up to 28% of pregnancies after trauma.22 The amount of Rh-positive fetal blood required to sensitize the Rh-negative mother is variable, but most patients are sensitized by as little as 0.01 ml of blood. The extent of fetomaternal hemorrhage and Rh alloimmunization is evaluated with the Kleihauer-Betke (KB) test. The test utilizes a stain that identifies fetal red blood cells with hemoglobin F in maternal blood. The ratio of fetal:maternal red blood cells can be assessed. Treatment with Rh immunoglobulin should be given early, along with obstetric consultation, but definitely within 72 hours of injury.

Premature Labor

Many cases of mild uterine contractions after trauma resolve spontaneously. Instances of true premature labor involve both preterm contractions and evidence of cervical dilation and may need to be treated with pharmacologic tocolytics. Several agents are available for tocolysis, including terbutaline and magnesium sulfate, and should only be administered with obstetric consultation. Traumatic injury, surgery, and general anesthesia may increase the risk of premature labor. Drost et al. reported an 80% efficacy using tocolysis in a study of major trauma in pregnancy.23 Blunt abdominal trauma may cause premature rupture of membranes leading to premature labor.

Amniotic Fluid Embolization

Amniotic fluid embolism refers to the entrance of amniotic fluid into the maternal circulation. It more commonly presents during labor or the immediate postpartum period, and the risk of maternal mortality is up to 80%. Pregnant trauma patients suffering from premature labor may be at risk. The diagnosis is mostly made on clinical signs, and the manifestations include severe dyspnea, hypoxia, hypotension, altered sensorium or seizures, and possible cardiac arrest. Respiratory failure mimics that seen in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. Patients may develop thrombocytopenia or DIC. Following fetal delivery, the maternal treatment for this condition is largely supportive. These supportive measures include supplemental oxygen or mechanical ventilation, fluid resuscitation, inotropes, vasopressors, and blood product replacement.24

Venous Thromboembolism

The hypercoagulable state associated with pregnancy is caused by an increase in coagulation factors and inhibition of fibrinolysis. The hypercoagulable state exacerbates conditions of prolonged immobilization in trauma patients with neurologic injury, pelvic or lower extremity fractures, and critical illness. Prophylaxis with subcutaneous low-molecular-weight heparin or low-dose unfractionated heparin, in combination with lower extremity intermittent pneumatic venous compression devices, is recommended. Heparin products do not cross the placental barrier and are considered safe during pregnancy. While warfarin products are contraindicated during pregnancy, patients may be transitioned to warfarin postpartum.

The method of radiological diagnosis for pulmonary embolism (PE) remains controversial.24 Winer-Muram et al. showed that the average fetal dose of ionizing radiation from a helical thoracic CT scan for PE is less than that with ventilation-perfusion lung scanning and was safe in all three trimesters.25 The utility of inferior vena caval filters for PE prophylaxis and the safety of thrombolytic agents for severe cases of PE have not been well studied.

Mortality

Reported fetal mortality rates due to trauma vary, but are as high as 61% for major trauma and 80% for maternal shock. Even minor trauma is associated with a 1%–5% fetal mortality. The incidence of significant maternal and fetal injury increases with gestational age, with slightly over 50% of injuries occurring in the third trimester. The most common cause of fetal death is maternal death followed by placental abruption. The most common mechanism associated with mortality for both mother and fetus is the MVC. This mechanism alone accounts for 82% of fetal deaths. It should be noted that the fetal death rate is affected by maternal age, with peak fetal death rates in mothers aged 15–19.26 This may reflect the greater propensity for patients in that age group to participate in risk-taking behavior such as alcohol and substance abuse, with an increased incidence of both MVCs and interpersonal violence.

The single most important measure to be taken to reduce mortality among pregnant women is the promotion of seatbelt use. The use of seatbelts results in a significant decrease in maternal (and hence fetal) mortality. It has been shown that along with crash severity, the use of seatbelts is the best predictor of maternal and fetal outcome.27 Three-point restraints should be used with the belt low on the pelvis, below the uterine fundus, with the shoulder belt placed between the breasts.

1 Lavery JP, Staten-McCormick M. Management of moderate to severe trauma in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 1995;22:69-90.

2 Baerga-Varela Y, Zietlow SP, Bannon MP, et al. Trauma in pregnancy. Mayo Clinic Proc. 2000;75(12):1243-1248.

3 Van Hook JW. Trauma in pregnancy. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2002;45(2):414-424.

4 Shah KH, Simons RK, Holbrook T, et al. Trauma in pregnancy: maternal and fetal outcomes. J Trauma. 1998;45(1):83-86.

5 McFarlane J, Campbell JC, Sharps P, et al. Abuse during pregnancy and femicide: urgent implications for women’s health. Obstet Gynecol. 2002;100(1):27-36.

6 American College of Surgeons. Advanced Trauma Life Support Course for Physicians, 5th ed. Chicago: American College of Surgeons, 1993.

7 Metcalfe J, McAnulty JH, Ueland K. Cardiovascular physiology. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1981;24:693-710.

8 Clark SL, Cotton DB, Lee W, et al. Central hemodynamic assessment of normal term pregnancy. Am Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:1439-1442.

9 Knudson MM, Rozycki GS, Strear CM. Reproductive system trauma. In: Mattox KL, Feliciano DV, Moore EE, editors. Trauma. 4th ed. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2000:879-906.

10 Yeomans ER, Gilstrap LCIII. Physiologic changes in pregnancy and their impact on critical care. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S256-S258.

11 Elkus R, Popovich JJr. Respiratory physiology in pregnancy. Clin Chest Med. 1992;13:555-565.

12 Awe RJ, Nicotra MB, Newsom TD, et al. Arterial oxygenation and alveolar-arterial gradients in term pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1979;197953:182-186.

13 Goodwin H, Holmes JF, Wisner DH. Abdominal ultrasound examination in pregnant blunt trauma patients. J Trauma. 2001;50(4):689-694.

14 Bochicchio GV, Haan J, Scalea TM. Surgeon-performed focused assessment with sonography for trauma as an early screening tool for pregnancy after trauma. J Trauma. 2002;52(6):1125-1128.

15 RD Barraco, WC Chiu & Clancy, et al Practice management guidelines for the diagnosis and management of injury in the pregnant patient. The EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group, Eastern Association for the Surgery of Trauma World Wide Web site. http://www.east.org/tpg/pregnancy.pdf

16 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee. Opinion #299: guidelines for diagnostic imaging during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:647.

17 Wakeford R, Little MP. Risk coefficients for childhood cancer after intra-uterine irradiation: a review. Int J Rad Biol. 2003;79(5):293-299.

18 Rogers FB, Rozycki GS, Osler TM, et al. A multi-institutional study of factors associated with fetal death in injured pregnant patients. Arch Surg. 1999;134(11):1274-1277.

19 Mattox KL, Goetzl L. Trauma in pregnancy. Criti Care Med. 2005;33(10):S385-S389.

20 Chiu WC, Shanmuganathan K, Mirvis SE, et al. Determining the need for laparotomy in penetrating torso trauma: a prospective study using triple-contrast enhanced abdominopelvic computed tomography. J Trauma. 2001;51:860-869.

21 Morris JAJr, Rosenbower TJ, Jurkovich GJ, et al. Infant survival after cesarean section for trauma. Ann Surg. 1996;223:481-491.

22 Rose PG, Strohm PL, Zuspan FP. Fetomaternal hemorrhage following trauma. Am Obstet Gynecol. 1985;153:844-847.

23 Drost TF, Rosemurgy AS, Sherman HF, et al. Major trauma in pregnant women: maternal/fetal outcome. J Trauma. 1990;30:574-578.

24 Moore J, Baldisseri MR. Amniotic fluid embolism. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:S279-S285.

25 Winer-Muram HT, Boone JM, Brown HL, et al. Pulmonary embolism in pregnant patients: fetal radiation dose with helical CT. Radiology. 2002;224:487-492.

26 Weiss HB, Songer TJ, Fabio A. Fetal deaths related to maternal injury. JAMA. 2001;286(15):1863-1868.

27 Pearlman MD, Klinich KD, Schneider LW, et al. A comprehensive program to improve safety for pregnant women and fetuses in motor vehicle crashes: a preliminary report. Am Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1554-1564.