19 Transmissible Spongiform Encephalopathy (Creutzfeldt–Jakob Disease)

Diagnosis

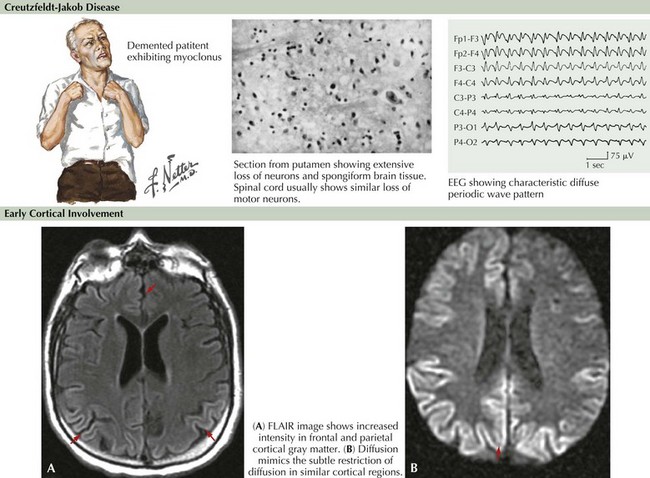

Brain MRI is now very useful in TSE diagnosis. In some cases of vCJD, bright lesions on T2-weighted and fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) imaging occur within the pulvinar, the so-called pulvinar sign. In CJD, focal hyperintense lesions may be found in the basal ganglia on T2-weighted images or multifocally within the cortex on diffusion-weighted images (Fig. 19-1). Diffusion-weighted MRI imaging has shown more than 90% sensitivity and specificity in some series, although the timing of MRI imaging along the course of illness is important. Repeated imaging may be required to detect typical changes. MRI abnormalities are also of supportive diagnostic value, similar to 14-3-3, but are not diagnostic of TSE. EEG may demonstrate 0.5- to 1-Hz periodic sharp waves focally or diffusely at some stage of the disease, particularly when there is clinical cerebral cortical dysfunction but certainly not all CJD individuals such as those presenting with cerebellar or striatal dysfunction. Nonspecific EEG slowing is more common but less specific than periodic sharp waves.

Appleby BS, Appleby KK, Crain BJ, et al. Characteristics of established and proposed sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease variants. Arch Neurol. 2009:208-215.

Brandel JP, Heath CA, Head MW, et al. Variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease in France and the United Kingdom: Evidence for the same agent strain. Ann Neurol. 2009 Mar;65(3):233-235.

Brown P. Transmissible spongiform encephalopathy in the 21st century: neuroscience for the clinical neurologist. Neurology. 2008 Feb 26;70(9):713-722. Review

Collins SJ, Sanchez-Juan P, Masters CL, et al. Determinants of diagnostic investigation sensitivities across the clinical spectrum of sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Brain. 2006;129:2278-2287.

Glatzel M, Stoeck K, Seeger H, et al. Human prion diseases; molecular and clinical aspects. Arch Neurol. 2005;62:545-552. Review

Goudsmit J. Obituary: Daniel Carleton Gajdusek (1923-2008). Nature. 2009 Jan 22;457(7228):394.

Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE, Parisi JE, et al. Rapidly progressive neurodegenerative dementias. Arch Neurol. 2009;66:201-207.

Kovacs GG, Budka H. Prion diseases: from protein to cell pathology. The American Journal of Pathology. 2008;172(3):555-565.

Shiga Y, Miyazawa K, Sato S, et al. Diffusion weighted MRI abnormalities as an early diagnostic marker for Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Neurology. 2004;63:443-449.

Ward HJ, Everington D, Cousens SN, et al. Risk factors for sporadic Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease. Ann Neurol. 2008 Mar;63(3):347-354.

Warren JD, Schott JM, Fox NC, et al. Brain biopsy in dementia. Brain. 2005 Sep;128:2016-2025. Review