Transient ischaemic attacks and prevention of strokes

A transient ischaemic attack (TIA) is an acute loss of neurological function or monocular vision caused by ischaemia with symptoms lasting less than 24 h. This occurs in 10% of patients prior to the development of a stroke. The annual incidence is 30 per 100 000.

A TIA is caused by artery-to-artery emboli or cardiac emboli. The pathogenesis is the same as for embolic stroke and is discussed on page 65. The investigation and management of TIAs and small strokes from which a good recovery has been made is the same because both provide a potential opportunity to prevent a more major stroke.

Clinical features

Anterior circulation TIAs include:

Posterior circulation TIAs include:

combined brain stem symptoms: vertigo, diplopia, dysphagia; these are rarely TIAs if they occur in isolation

combined brain stem symptoms: vertigo, diplopia, dysphagia; these are rarely TIAs if they occur in isolationAnterior or posterior circulation TIAs include:

A history of risk factors for atheroma is important (see Table 1, p. 64). In young women, the type of oral contraceptive is important: the combined oestrogen–progestogen pill increases their risk by two to three times, but there is no increased risk with progesterone only.

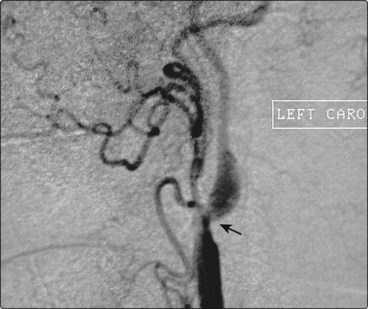

Examination of a patient following a TIA usually reveals no neurological abnormalities. Occasionally a cholesterol embolus is seen on fundoscopy (Fig. 1). The cardiovascular system is more likely to reveal relevant abnormalities such as hypertension, hypertensive retinal changes, arrhythmias, heart murmur, signs of cardiac failure suggesting left ventricular dysfunction, loss of peripheral pulses and bruits.

Differential diagnosis

Migraine: there is usually a slower progression of the neurological deficit, taking 15–30 min to develop; there are usually positive symptoms such as flashing lights or marked tingling associated with this. There is usually an associated migrainous headache.

Migraine: there is usually a slower progression of the neurological deficit, taking 15–30 min to develop; there are usually positive symptoms such as flashing lights or marked tingling associated with this. There is usually an associated migrainous headache. Partial seizures: these are usually much shorter lived, lasting seconds to a few minutes; when they recur they are very stereotyped.

Partial seizures: these are usually much shorter lived, lasting seconds to a few minutes; when they recur they are very stereotyped. Transient global amnesia: this causes profound anterograde amnesia, lasting hours, with normal physical function.

Transient global amnesia: this causes profound anterograde amnesia, lasting hours, with normal physical function.Investigation

Investigation is directed at looking for risk factors for vascular disease, potential sources of embolism in either the carotid arteries or in the heart, causes of tendency to thrombosis and causes of inflammatory vascular disease (see Table 1, p. 64). The investigations need to be tailored to the patient. Younger patients will require more aggressive investigation, particularly if there are no risk factors for atheroma. In these patients, careful evaluation of the heart and screening for thrombophilia and possible vasculitic processes are needed. Screening for sickle cell disease is indicated in all patients at risk.

Secondary prevention of stroke and transient ischaemic attacks

Carotid stenosis

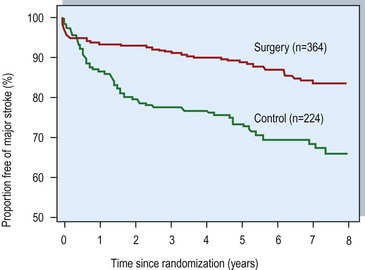

The North American Symptomatic Carotid Endarterectomy study and the European Carotid Surgery trials are landmark studies that evaluated the usefulness of this surgical procedure in a range of degrees of carotid stenosis (Fig. 2). Both studies found a reduced risk of recurrent stroke in patients with a greater than 70% stenosis in the surgical group and especially those with stenosis greater than 80% (Fig. 3). The benefit of surgery depends on achieving a low surgical morbidity and mortality (7% or less). The risk of stroke is greater with a tighter stenosis and if the plaque is ulcerated, so the benefit is greater for these patients. An occluded carotid artery poses no further risk of embolic stroke.