Chapter 12 Traditional systems of herbal medicine

Introduction

Three types of traditional medicine have been chosen as an illustration:

• Traditional Chinese Medicine (TCM)

• Traditional African medicine (TAM) or traditional African medical systems (TAMS).

Correlation of traditional use with scientific evidence

• in the Caribbean the periwinkle Catharanthus (Vinca) rosea was used traditionally for treating diabetes, but on further investigation it yielded the powerful anticancer alkaloids vincristine and vinblastine

• Fagara xanthoxyloides, which is used in Nigeria as a chewing stick for cleaning the teeth, has been found not only to be antimicrobial, but also to have antisickling activity, and this finding has sparked off further work into this painful and chronic genetic condition.

Traditional chinese medicine

The study of TCM is a mixture of myth and fact, stretching back well over 5000 years. At the time, none of the knowledge was written down, apart from primitive inscriptions of prayers for the sick on pieces of tortoise carapace and animal bones, so a mixture of superstition, symbolism and fact was passed down by word of mouth for centuries. TCM still contains very many remedies, which were selected by their symbolic significance rather than proven effects; however, this does not necessarily mean that they are all ‘quack’ remedies! There may even be some value in medicines such as tiger bone, bear gall, turtle shell, dried centipede, bat dung and so on. The herbs, however, are well researched and are becoming increasingly popular as people become disillusioned with Western medicine. Again, Chinese medicine is philosophically based, and as an holistic therapy the concept of balance and harmony is supremely important. The relevant records and documents were discussed earlier (Chapter 2), but additional historical milestones will be included here to show the evolution of TCM into what it is today.

Concepts in TCM

Yin and yang

Yin is considered to be the stronger: fire is extinguished by water, and water is ‘indestructible’. So yin is always mentioned before yang; however, they are always in balance. Consider the well-known symbol (Fig. 12.1): where yin becomes weak, yang is strong and vice versa. Both contain the seed of each other: their opposites within themselves.

Diagnosis

• Examination of the tongue: a very important aspect

• Pulse diagnosis: more than one pulse will be taken, depending on the pressure exerted

• Palpation of internal organs: carried out to determine consistency and tone

• Massage: used to detect temperature and knotted muscles or nerves

• Interviewing: vital; questions are asked about sleep patterns, tastes in food and drink, stool and urine quality, fever, perspiration and sexual activity.

Treatment

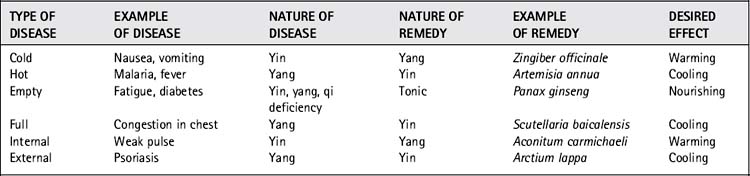

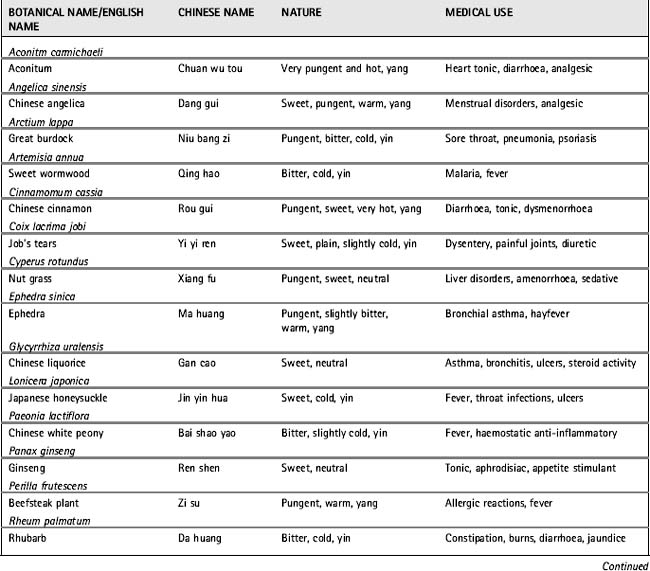

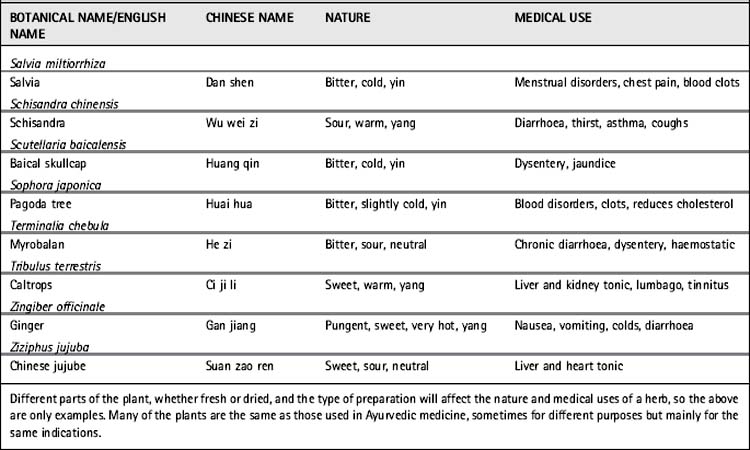

The purpose is to rectify harmony, restore qi and the yin/yang balance. For example ‘cold’ diseases, such as cold in the lungs, coughs, vomiting and nausea are considered to be a deficiency of yang and treatment would be with a warming herb such as ginger (see examples in Table 12.1). A list of common herbs and their indications is given in Table 12.2. Once the prescription has been formulated, the patient may be given a crude herb mixture with written instructions on how to prepare it at home, perhaps as an infusion or tea. Pastes and pills are prepared by the herbalist and may take several days to complete. Slow-release preparations are made using beeswax pills; tonic wines, fermented dough (with herbs in) and external poultices are also common.

Ayurveda

Concepts in ayurveda

Tridosha: vata, pitta and kapha – the three humors

• Vata, affiliated to air or ether (space), is a principle of movement. It can be characterized as the energy controlling biological movement and is thus associated with the CNS, and governs functions such as breathing, blinking, all forms of movement, heartbeat and nervous impulses.

• Pitta is affiliated to fire and water, and governs bodily heat and energy. It, therefore, controls body temperature, is involved in metabolism, digestion, excretion and the manufacture of blood and endocrine secretions, and is also involved with intelligence and understanding.

• Kapha is associated with water and earth. It is responsible for physical structure, biological strength, regulatory functions, including that of immunity, the production of mucus, synovial fluid and joint lubrication and assists with wound healing, vigour and memory retention.

Prakruti, the human constitution

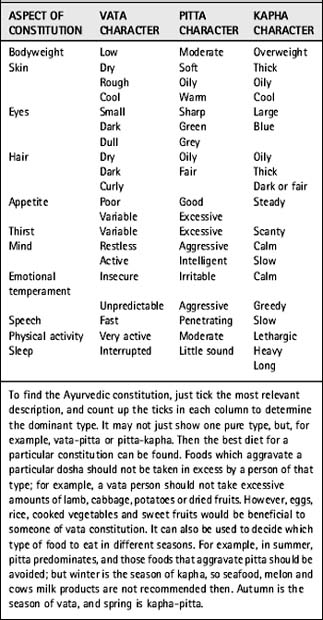

Humans can also be divided into personality types, and the constitution of an individual (prakruti) is determined by the state of the parental tridosha at conception (unlike astrology, which depends on time of birth). Most people are not completely one type or another, but can be described as vatapitta or pittakapha, for example. People of vata constitution are generally physically under-developed with cold, rough, dry and cracked skin. People with pitta constitution are of medium height with moderate muscle development. Kapha people have well-developed bodies. Table 12.3 can be used to indicate constitution in a superficial way, but it is not a tool for self-diagnosis!

Gunas, the attributes

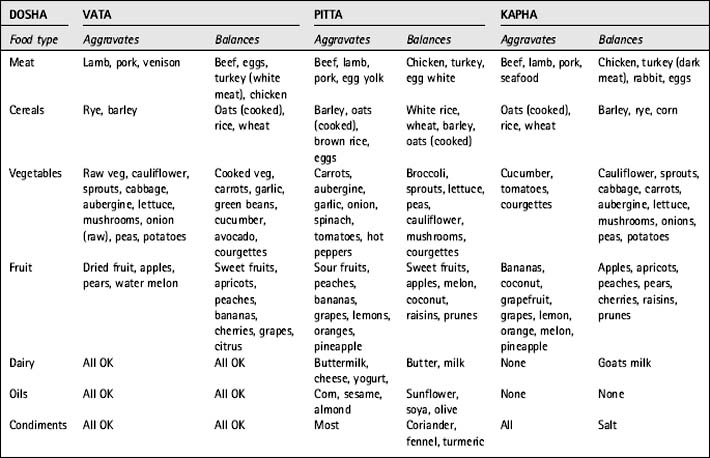

Ayurveda encompasses a subtle concept of attributes or qualities called gunas. Caraka, the great Ayurvedic physician, theorized that organic and inorganic substances, as well as thought and action, all have definite attributes. These attributes contain potential energy while their associated actions express kinetic energy. Vata, pitta and kapha each have their own attributes, and substances having similar attributes will tend to aggravate the related bodily humor. The concepts governing the pharmacology, therapeutics and food preparation in Ayurveda are based on the action and reaction of the attributes to and upon one another. Through understanding of these attributes, the balance of the tridosha may be maintained. The diseases and disorders ascribed to vata, pitta and kapha are treated with the aid of medicines, which are characteristic of, but possessing the opposite attribute, to try and correct the deficiency or excess. Vata disorders are corrected with the aid of sweet (madhur), sour (amla) or saline and warm (lavana) medicines. The excitement or ‘aggravation’ of pitta is controlled by sweet (madhur), bitter (katu) or astringent and cooling (kashaya) herbs. Kapha disorders are corrected with pungent (tikta), bitter (katu) or astringent and dry (kashaya) herbs. The use of herbs in correcting any imbalance is of extreme importance and is essential for proper functioning of the organism. There is often little distinction between foods and medicines, and controlling the diet is an integral part of Ayurvedic treatment. Foods are also described according to their properties, such as their taste (rasa) and physical and chemical properties (guna); these affect the tridosha (see Table 12.4).

Application of ayurveda

Treatment

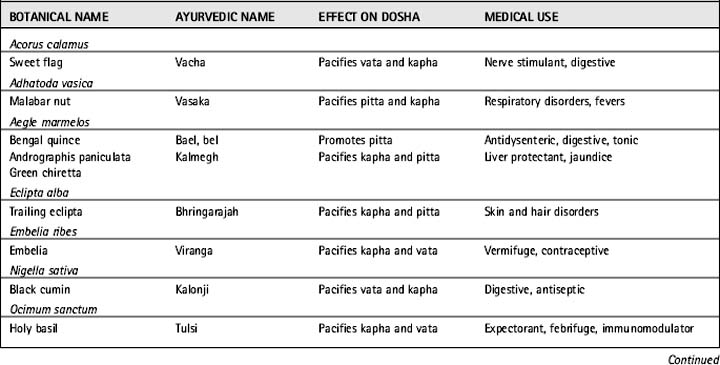

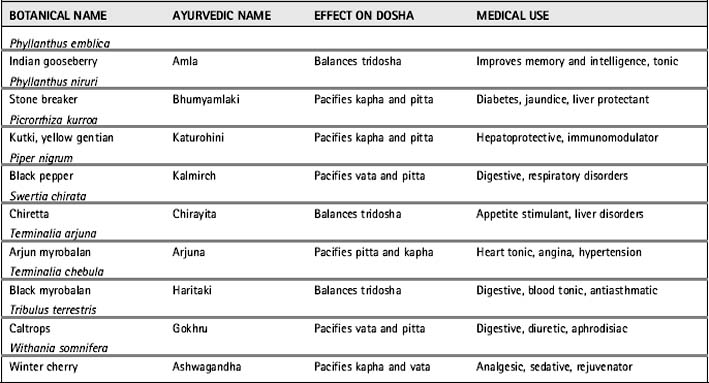

This may involve diets, bloodletting, fasting, skin applications and enemas used to cleanse the system. There is a programme consisting of five types of detoxification, known as panchkarma. Drugs may then be given to bring the dhatus into balance again. These include herbal treatments as well as minerals, and there are thousands in use. In addition, yogic breathing and other techniques are used. All will have their properties described: rasa, guna and their karma, as well as which doshas they affect. Some of the most popular herbes of Ayurveda are shown in Table 12.5.

In modern Indian herbal medicine the Ayurvedic properties are described together with the conventional pharmacological and phytochemical data. Drugs are prepared as tinctures, pills, powders and some formulae unique to Ayurveda (see Table 12.6). Ayurveda is very metaphysical, too much so for many Westerners to grasp, and practitioners view it as a way of life as opposed to a career.

| Formulation | Method of production |

|---|---|

| Juice (swaras) | Cold-pressed plant juice |

| Powder (churna) | Shade-dried, powdered plant material |

| Cold infusion (sita kasaya) | Herb/water 1:6, macerated overnight and filtered |

| Hot infusion (phanta) | Herb/water 1:4, steeped for a few minutes and filtered |

| Decoction (kathva) | Herb/water 1:4 (or 1:8, 1:16 then reduced to 1:4), boiled |

| Poultice (kalka) | Plant material pulped |

| Milk extract (ksira paka) | Plant boiled in milk and filtered |

| Tinctures (arava, arista) | Plant fermented, macerated or boiled in alcohol |

| Pills or tablets (vati, gutika) | Soft or dry extracts made into pills or tablets |

| Sublimates (kupipakva rasayana) | Medicine prepared by sublimation |

| Calcined preparations (bhasma) | Plant or metal is converted into ash |

| Powdered gem (pisti) | Gemstone triturated with plant juice |

| Scale preparations (parpati) | Molten metal poured on leaf to form a scale |

| Medicated oils or ghee (sneha) | Plant heated in oil or ghee |

| Medicated linctus/jam (avaleha) | Plant extract in syrup |

Traditional african medical systems

Concepts in traditional african medical systems

• Confessions may be extracted. These are thought to be both healing and prophylactic. In the case of a child, the mother may need to examine her previous behaviour, since the sins of the mother can be visited on the child (this compares with ideas in Christianity and other religions).

• Divination may be required, and may involve throwing objects and interpreting the pattern in which they fall. This is a consistent feature of many cultures and still persists in Europe in such forms as the ‘reading of tea leaves’.

In TAMS, medicinal plants are used in two ways, only one of which corresponds to our perception of drug therapy. When we talk of research into traditional medicines, we are really talking about the scientific analysis of medicinal plants. Some of the most commonly used African ones are listed in Table 12.7. The traditional healer will, however, use medicinal plants not only for their pharmacological properties but their power to restore health as supernatural agents. This is based on two important assumptions:

• Plants are living and it is thought that all living things generate a vital force, which can be harnessed.

• The release of the force may need special rituals and preparations such as incantations to be effective. This belief is rather similar to the concept held by some people nowadays that uncooked vegetables, particularly things such as sprouting beans, somehow contain a ‘life-force’ which is beneficial to health.

Table 12.7 Examples of common and widely used African medicinal plants and the main conditions for which they are used

| Species | Indigenous use |

|---|---|

| Rauvolfia vomitoria (Apocynaceae) Holarrhena wulfsbergii (Apocynaceae) | Mental illness (especially schizophrenia) |

| Xylopia aethiopica (Annonaceae) Piper guineense (Piperaceae) |

Oedema |

| Pycnanthus kombo (Myristicaceae) Aframomum latifolium (Zingiberaceae) Harpagophytum procumbensa (Pedaliaceae) |

Pain, inflammation, lumbago |

| Plumbago zeylanica (Plumbaginaceae) Cassia alata (Caesalpiniaceae) |

Skin diseases |

| Elaeophorbia drupifera (Euphorbiaceae) Picralima umbellata (Apocynaceae) |

Worms |

| Ricinus communis (Euphorbiaceae) Carica papaya (Caricaceae) |

Contraceptive |

| Diospyros mespiliformis (Ebenaceae) Ficus elegans (Moraceae) |

Dysentery, diarrhoea |

| Prunus africanaa (Rosaceae) | Male urinary problems |

a Developed into phytomedicines used in Europe and North America.

Govindarajan R., Vijayakumar M., Pushpangadan P. Antioxidant approach to disease management and the role of Rasayana herbs of Ayurveda. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2005;99:165-178.

Lad V. Ayurveda the science of self-healing. Wisconsin: Lotus Press; 1990.

Mukherjee P.K., Mukherjee D., Venkatesh M., Rai S., Heinrich M. The sacred lotus (Nelumbo nucifera) – phytochemical and therapeutic profile. J. Pharm. Pharmacol.. 2009;61:407-422.

Neuwinger H.D. African traditional medicine. Stuttgart: Medpharm; 2000.

Okpako D.T. Traditional African medicine: theory and pharmacology explored. Trends Pharmacol. Sci.. 1999;20:482-485.

Sairam T.V. Home remedies. India: Penguin, 2000;vols. I–III.

Sofowara A., editor. African medicinal plants: Proceedings of a conference. Nigeria: University of Life Press, 1979.

Thomas O.O. Perspectives on ethno-phytotherapy of Yoruba medicinal herbs and preparations. Fitoterapia. 1989;60:49-60.

Williamson E.M., editor. Major herbs of Ayurveda. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone, 2002.