Tracheotomy and Cricothyrotomy

Surgical Anatomy and Tracheotomy Procedure

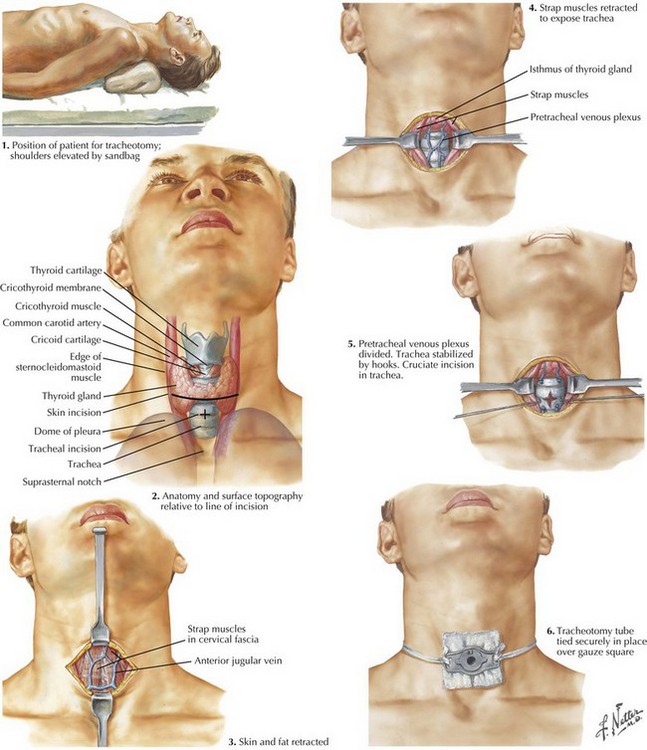

The patient is placed in the supine position. The surgeon might consider placing the neck into slight extension, but this should not be too far past the neutral position, so that the skin incision remains in line with the tracheal incision. A shoulder roll may be used in some patients to assist with positioning (Fig. 2-1).

The thyroid notch superiorly, cricoid cartilage, and suprasternal notch inferiorly can usually be palpated and should be marked (Fig. 2-1). If an awake tracheotomy is being performed, the skin is injected with 1% lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine solution for hemostasis and anesthesia. According to surgeon preference, this injection may also be done for general anesthesia patients. A vertical or horizontal incision is made in the midline of the neck, about 2 cm above the sternal notch, and is carried down until the strap muscles are visible.

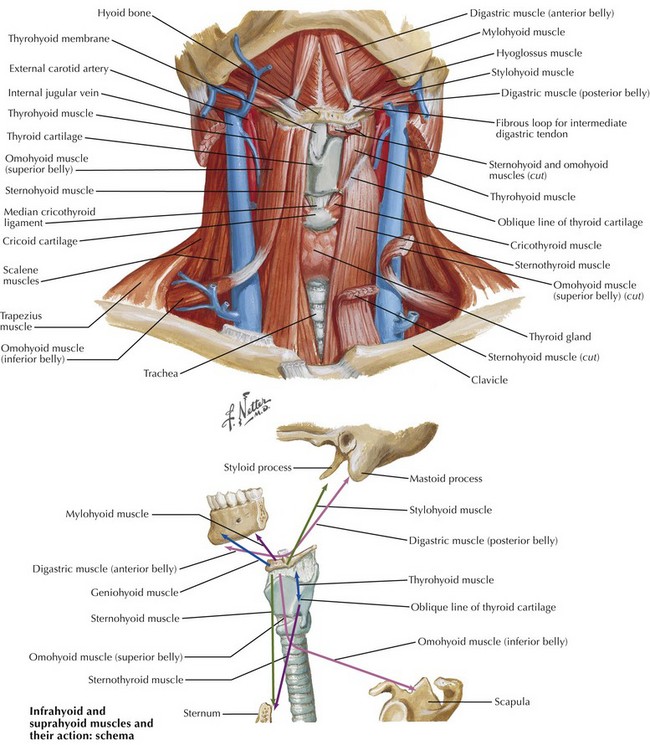

Strap Muscles and Midline Raphe

The anterior jugular veins are typically located on the strap musculature and may require ligation if encountered in the midline (Fig. 2-2). Small cricothyroid arteries traverse the superior aspect of the cricothyroid space, forming an anastomosis near the midline. This may cause problematic bleeding in the setting of emergent airway access or if dissection is carried out above the cricoid cartilage. In the lower neck, the surgeon must be aware that the innominate artery crosses over anterior to the trachea at the level of the thoracic inlet and is higher on the right side. Before dissection of the strap muscles, the surgeon should palpate for innominate pulsations in the suprasternal notch and should be cognizant of the pathway of the surgical dissection in the setting of a high-riding vessel.

Bailey, BJ. Head and neck surgery: otolaryngology, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 2006.

Beatrous, WP. Tracheostomy: its expanded indications and its present status. Laryngoscope. 1968;78(3):3–55.

Pahor, AL. Ear, nose and throat in ancient Egypt. J Laryngol Otol. 1992;106(9):773–779.

Shapiro, BA, Harrison, RA, Trout, CA. The artificial airway: clinical application of respiratory care, 2nd ed. Chicago: Year Book; 1979.