Upper Extremity Arteriovenous Access for Hemodialysis

Preoperative Evaluation

Preoperative Vessel Mapping by Duplex Ultrasound

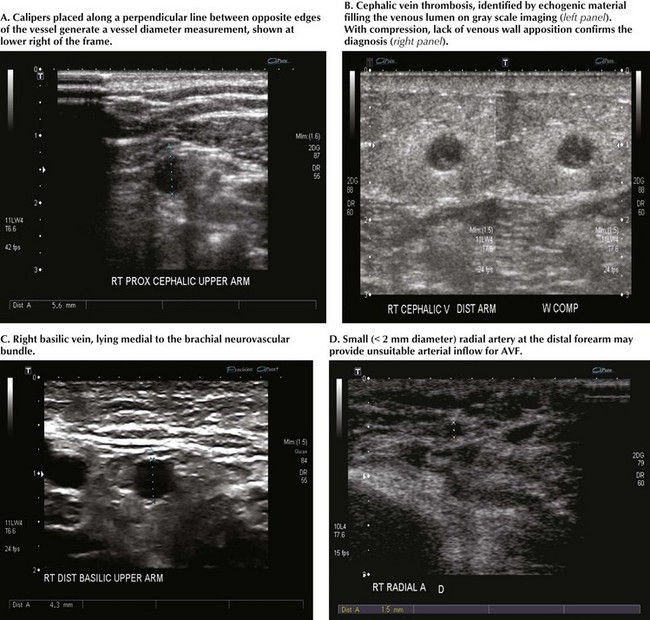

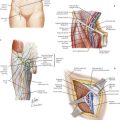

Standard vessel-mapping protocols provide important information regarding approach to the best AVF or AVG location. Cephalic vein diameter is shown in Figure 35-1, A. Venous fibrosis, identified by thickened vein walls or incomplete compressibility, may predict poor distensibility with arterial inflow. Thrombosis from venipuncture or IV placement is shown in gray-scale imaging (Fig. 35-1, B). The basilic vein often lies deep and medial in the arm and will need superficialization if used for AVF (Fig. 35-1, C). A small or heavily calcified radial artery at the wrist, a common finding in diabetic patients, may contraindicate use of this artery for inflow (Fig. 35-1, D).

Arteriovenous Fistulas

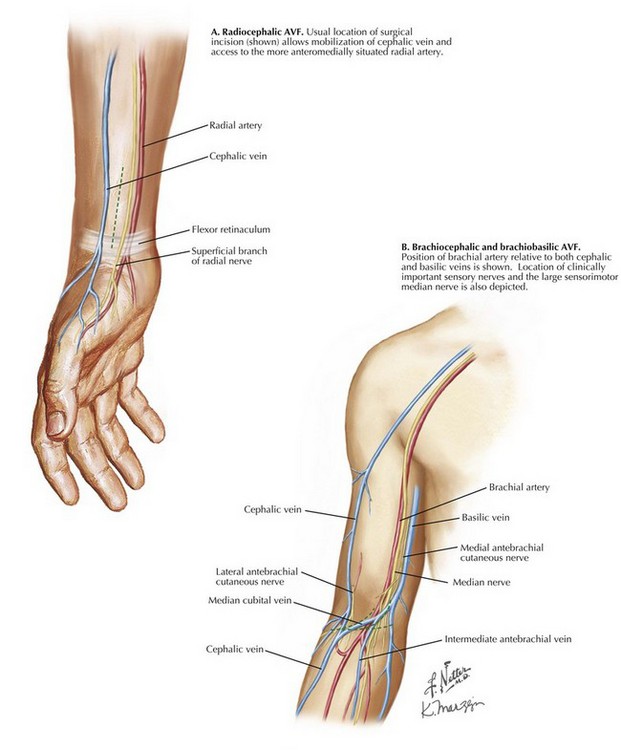

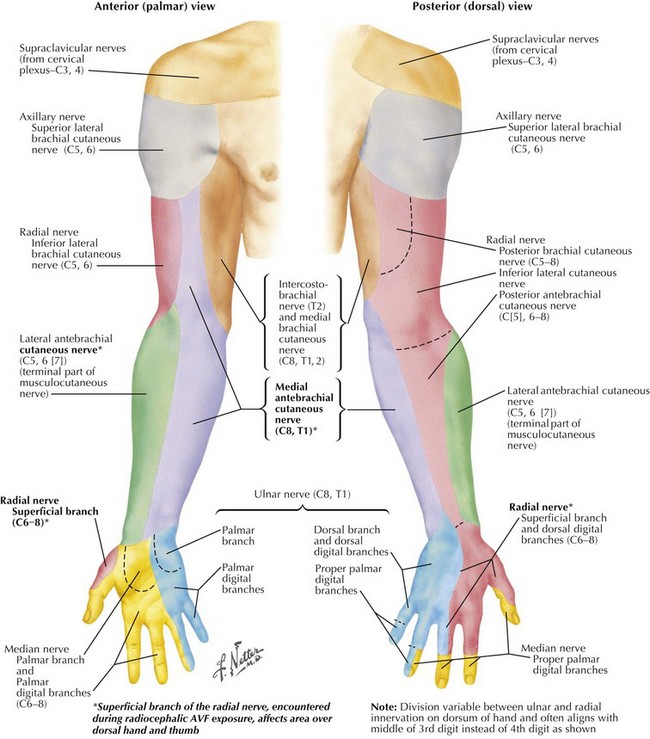

The approach for radiocephalic AVF is through a longitudinal skin incision along the anterolateral distal forearm that allows exposure of both the cephalic vein and the radial artery proximal to the flexor retinaculum. The superficial branch of the radial nerve, a small sensory branch, is often identified in the surgical field; excessive traction or transection may cause annoying numbness along the posterior thumb or lateral dorsum of the hand (Fig. 35-2, A; see also later Fig. 35-4).

After dilation and maturation, fistula cannulation takes place on the dorsolateral forearm.

Brachiocephalic Fistula

The approach for brachiocephalic AVF is through a transverse or curvilinear skin incision at or just distal to the antecubital crease, where cephalic vein is close to the distal brachial artery (Fig. 35-2, B). The cephalic vein must be mobilized sufficiently to deliver it medially and into the deeper plane, where the brachial artery resides. Radial artery takeoff is variable and may occur anywhere between axillary artery and brachial artery terminus. A smaller-caliber artery encountered in the more superficial incision may represent radial artery variation. In this case, clamping of brachial artery will not diminish radial artery pulsation at the wrist.

Toward the brachial artery terminus, the large median nerve diverges medially but may still be encountered close to the artery at this level. This important sensorimotor nerve should be preserved. Interruption of smaller sensory nerves, such as branches of lateral or medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves, may result in annoying numbness over lateral or medial forearm, respectively (see Fig. 35-4).

Once mature, cannulation of brachiocephalic AVF takes place on the anterior arm.

Prosthetic Arteriovenous Graft

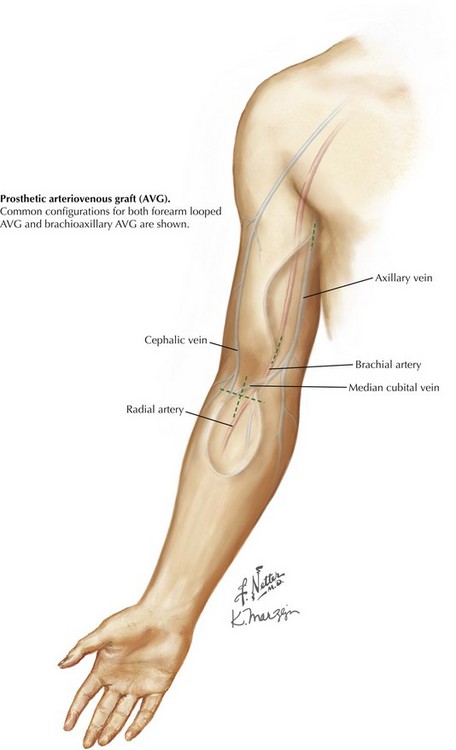

This common configuration places a loop of prosthetic material between arterial and venous circulations. The forearm looped approach is by transverse or longitudinal skin incision in the proximal forearm, just below the antecubital crease (Fig. 35-3). This approach allows exposure of both the inflow artery, usually the brachial artery terminus or proximal radial artery, and an outflow vein, either median cubital or median cephalic/basilic, depending on anatomy. If no antecubital surface vein is suitable, a deep brachial vein may be accessible through the same exposure.

Cutaneous Innervation of Upper Limb

Annoying sensory deficits can be caused by cautery or retraction trauma or by division of smaller nerve branches. The superficial branch of the radial nerve, encountered during radiocephalic AVF exposure, affects the area over the dorsal hand and thumb. Lateral and medial antebrachial cutaneous nerves, encountered during distal brachial exposure, affect forearm areas colored green and purple, respectively, in Figure 35-4.

National Kidney Foundation. KDOQI clinical practice guidelines and clinical practice recommendations for 2006 update: vascular access. Am J Kidney Dis. 2006;48(Suppl 1):S176–276.

Scher, LA, Vesely, TM. Hemodialysis access: perspectives for current clinical practice. Semin Vasc Surg. 20(3), 2007.

Davidson, I. On call in… vascular access: surgical and radiologic procedures. Austin, Texas: Landes Bioscience; 1996.