Tracheostomy Care

Introduction

Placement of a tracheostomy tube is a common procedure in critically ill patients. Common indications for this procedure include upper airway obstruction, head or neck trauma, and prolonged respiratory failure.1,2 Approximately one fourth of patients in the intensive care unit (ICU) will require a tracheostomy tube for prolonged respiratory support or weaning from mechanical ventilation.3 Advances in health care allow many patients with tracheostomies to live at home or in other relatively low-technology environments such as rehabilitation facilities and nursing homes. As a result, tracheostomy care is often provided by a variety of caregivers, including family members, home health care nurses, and patient care technicians.4,5

Patients with tracheostomies are seen in emergency departments (EDs) for a variety of problems related to the tracheostomy.6 Common complaints include difficulty breathing as a result of tube obstruction, tube displacement, or equipment failure; poor oxygenation from infection or altered patient anatomy; and bleeding. In some cases, complications can be life-threatening. Emergency physicians must be knowledgeable regarding the evaluation and management of patients with tracheostomies. This chapter reviews the relevant tracheal anatomy and essential tracheostomy equipment, discusses pertinent tracheostomy care, provides a systematic approach to the evaluation and management of selected complications, and identifies high-risk patient populations.

Background

Most tracheostomies are performed electively. For elective tracheostomies, the surgical site is between the first and second or the second and third tracheal rings. With an open, or surgical, tracheostomy, the anterior aspect of the trachea is generally left sutured to the skin until the tract matures, approximately 4 to 5 days after the procedure. In recent years, percutaneous dilational tracheostomy has become the preferred technique for many ICU patients. It can be performed at the bedside and eliminates the risks associated with transporting critically ill patients to an operating room. Postoperative complications vary and depend on the timing and insertion technique (Box 7-1). Early postoperative complications tend to arise in days to weeks. Sixteen percent to 20% of patients experience early complications, and 6% to 8% experience late complications.7 Although elective and emergency tracheostomies are generally performed with the same technique, the complication rate associated with emergency procedures may be higher than the rate for elective tracheostomies.8–10

Tracheal Anatomy and Physiology

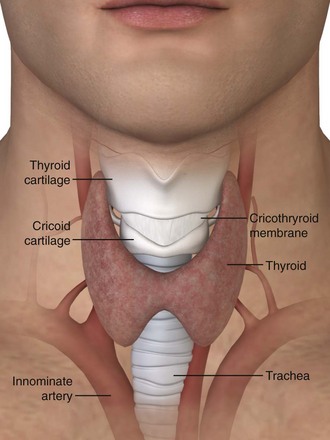

The lower respiratory tract begins at the vocal cords. Inferior to the vocal cords lies the cricoid cartilage, which encases the 1.5- to 2-cm subglottic space. Inferior to the cricoid cartilage is the trachea (Fig. 7-1). The typical adult trachea is 10 to 12 cm in length. The anterior and lateral walls of the trachea are supported by 18 to 22 incomplete cartilaginous rings. A fibromuscular sheet lying anterior to the esophagus completes the posterior wall. The interior diameter of the adult trachea is 12 to 25 mm, and it is lined with mucosa covered by respiratory epithelium.8 Blood is supplied to the trachea by branches of the inferior thyroid, innominate (brachiocephalic), bronchial, and subclavian arteries. Critically, the innominate artery (IA) lies in close proximity to the tracheostomy stoma. From its origin at the aortic arch, the IA courses between the sternum and the anterior aspect of the trachea and veers right at the sternomanubrial joint. The location of the IA is important because erosion of the anterior tracheal wall can lead to life-threatening bleeding. The recurrent laryngeal nerve innervates the intrinsic laryngeal muscles and mucosa below the vocal cords. Efferent vagal fibers stimulate bronchoconstriction, mucosal secretions, and vasodilation. Efferent sympathetic fibers of the pulmonary plexus stimulate tracheal bronchodilation and vasoconstriction.

Figure 7-1 Tracheal anatomy.

The upper airway, including the oropharynx and nasal passages, filters particulate matter, humidifies inspired air, and aids in the expectoration of secretions. These functions are reduced in patients with a tracheostomy.8 Placement of a tracheostomy bypasses humidification and results in the formation of thick, dry secretions.11 In the absence of humidification, squamous metaplasia and chronic inflammatory changes develop in the trachea.12 Bronchoconstriction resulting in reduced airflow can occur if the inspired air temperature is below room temperature. Normal mucociliary clearance is also impaired because of the increased viscosity of respiratory secretions, which underlies chronic illness and respiratory infections, particularly with Mycoplasma or viral pathogens.13

The tracheostomy procedure weakens the anterior tracheal wall and blunts the normal cough mechanism, an important component for clearance of secretions by the trachea.13 Normally, the epiglottis and vocal cords close to trap air in the lungs and raise intrathoracic pressure before a cough. Patients with a tracheostomy tube are generally unable to generate sufficient pressure to initiate a strong cough and facilitate airway clearance.14 In addition to an impaired cough mechanism, immune responses are often blunted in patients with tracheostomies as the result of underlying illnesses, chronic lung disease, chemotherapy, or acquired immunosuppression.

General Equipment for Tracheostomy Patients

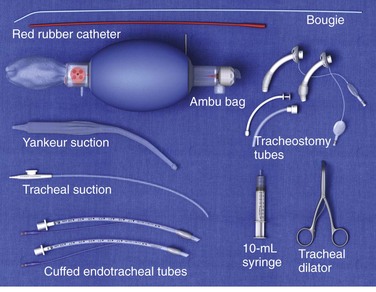

Before performing any procedure on the tracheostomy tube, it is important that the emergency physician ensure that essential equipment is readily available at the patient’s bedside. These items are shown in Figure 7-2. Adequate preparation is crucial in preventing a poor outcome should complications arise. Most of this equipment can be placed in a designated airway box that can easily be accessed within the room or ED.

Figure 7-2 Suggested equipment for tracheostomy care.

Routine Tracheostomy Maintenance

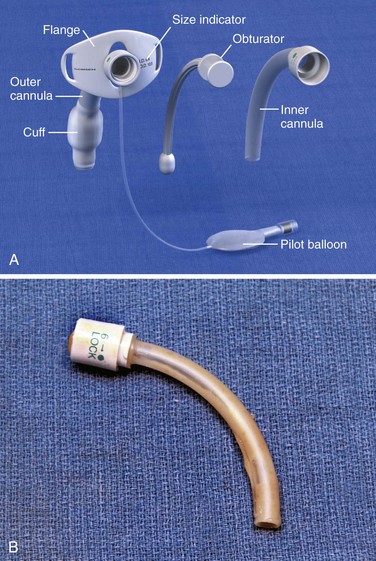

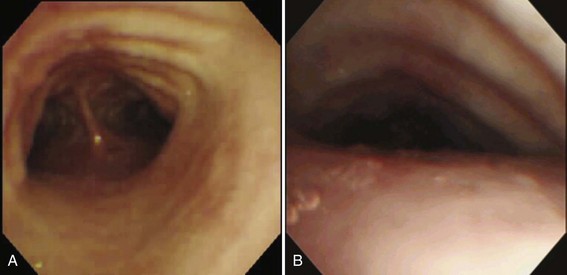

Routine tracheostomy maintenance involves (1) regular cleaning of the tube, (2) frequent stomal care, and (3) periodic monitoring of cuff pressure. There are many different types of tracheostomy tubes, but the focus of this section is on the most common types of tracheostomy tubes, those with a removable inner cannula (Fig. 7-3A). Regular cleaning of the tracheostomy tube and inner cannula can prevent the accumulation of dried secretions. Lack of cleaning and maintenance of the inner cannula is the primary cause of tube obstruction (Fig. 7-3B). Under normal circumstances the inner cannula should be in place. It sits snugly within the tracheostomy tube and can easily be removed without disturbing the tube itself. The inner cannula should be cleaned daily. Soak it in a half-strength hydrogen peroxide solution for 10 to 15 minutes and remove encrustations with a soft-bristle tracheostomy brush.15 Clean dried debris and blood from the tracheostomy tube flanges as well. To prevent damage to the tracheal mucosa, rinse all airway equipment with sterile saline before reinsertion.16 Important stomal wound care includes changing contaminated tube ties, cleaning the tube flanges regularly, and using pre-cut tracheostomy gauze. Loose fibers from hand-cut gauze may induce inflammatory changes at the stomal site.14

The tracheostomy cuff provides a tight seal to allow positive pressure ventilation and prevent aspiration. Cuff pressure should ideally be maintained below 25 mm Hg.16 Overinflation is common and can cause disastrous injury to the tracheal wall and mucosa and lead to tracheomalacia, tracheal stenosis, or the development of a fistula between surrounding anatomic structures.17 It is a good practice to regularly check and document cuff pressure with a handheld pressure manometer to document inflation volumes. If an air leak occurs at the maximum recommended cuff pressure, the tube may have become dislodged, which requires further evaluation.

Ventilating Tracheostomy Patients

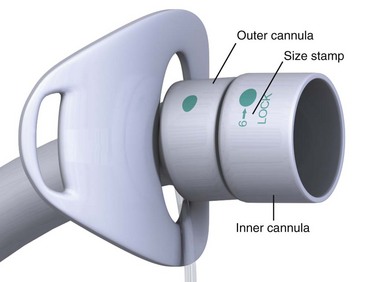

To properly ventilate ED patients with a tracheostomy, it is important to determine the make, model, and type of tube (Fig. 7-4). For proper ventilation, a 15-mm adapter must be present, either on the tube itself or on the end of an inner cannula that has an inflatable cuff. The inner cannula adapter will accept an Ambu bag or ventilator tubing, and the cuff will allow positive pressure ventilation. If the patient requires manual or mechanical ventilation and the tracheostomy tube is not suitable for ventilatory support, immediately replace it with a 6-0 cuffed endotracheal (ET) tube for ventilation.

Tracheal Suctioning

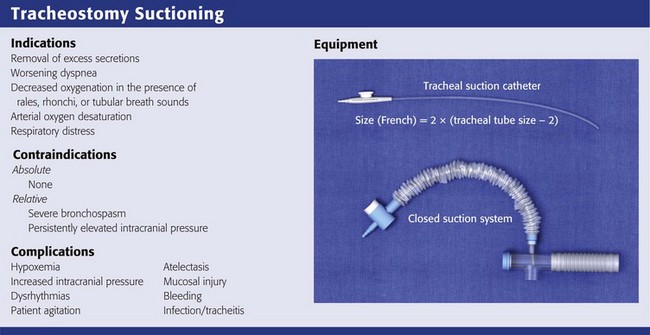

Indications

The primary indications for tracheal suctioning are to remove secretions, enhance oxygenation, or obtain samples of lower respiratory tract secretions for diagnostic tests. In the ED, tracheal suctioning should be performed to enhance oxygenation in any tracheostomy patient in respiratory distress. In addition, tracheal suctioning should be performed when the patient has coarse rales, rhonchi, or tubular breath sounds; acute or worsening dyspnea; or arterial oxygen desaturation. It is important to emphasize that tracheal suctioning should be performed only when it is clinically indicated; frequent, routine suctioning is not recommended.18,19

There are no absolute contraindications to tracheal suctioning. Relative contraindications include severe bronchospasm, which may worsen with suctioning, and persistently elevated intracranial pressure (ICP), which is exacerbated by suctioning.20 Bronchodilators, sedatives, and paralytics may alleviate these symptoms. Tracheal suctioning should be undertaken with caution in patients with cardiovascular instability because of an increased risk for associated dysrhythmias.21

Equipment

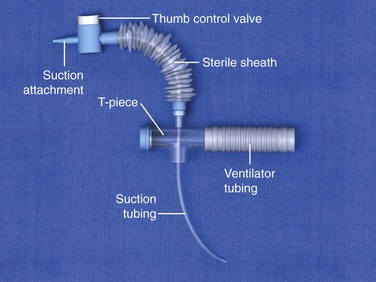

A suction catheter and vacuum system, open or closed, is required to perform tracheal suctioning (Fig. 7-5). It is recommended that the diameter of the suction catheter be no larger than half the inner diameter of the tracheostomy tube.22,23 The size of the suction catheter in French gauge (Fg) can be calculated as follows:

For example, a 7-0 tracheostomy tube will require a 10-Fg suction catheter because 2 × (7 − 2) = 10 Fg. If the catheter is too small, it will not remove excess secretions adequately. If the catheter is too large, it can obstruct airflow during insertion and cause alveolar collapse with resultant hypoxemia.

Figure 7-5 Closed-system suction catheter.

In adults, the suction catheter should be inserted only 10 to 15 cm, depending on the length of the tracheostomy tube. The goal of suctioning is to remove secretions only from the proximal airways. Shallow suctioning occurs when the catheter is placed just beyond the hub of the tracheostomy tube to remove proximal secretions. Premeasured suctioning occurs when a catheter is inserted such that the distal side ports are beyond the caudal end of the tracheostomy tube. Deep suctioning occurs when the suction catheter is advanced until resistance is met. It is used for clearing excess secretions in the lower airways.19 Deep suctioning has not been shown to be more beneficial than shallow suctioning and should not be performed routinely because it might damage the mucosal epithelium and lead to an increase in granulation tissue.24,25

A closed-system airway encases a suction catheter in a sterile sheath attached to ventilator tubing. This prevents the suction catheter from being contaminated by contact with the outside environment and allows tracheal suctioning to be performed without interrupting ventilatory support. The vacuum should be set to the lowest possible pressure to reduce atelectasis. Vacuum pressure should not exceed 80 mm Hg in infants or 150 mm Hg in adults.22

Procedure and Technique

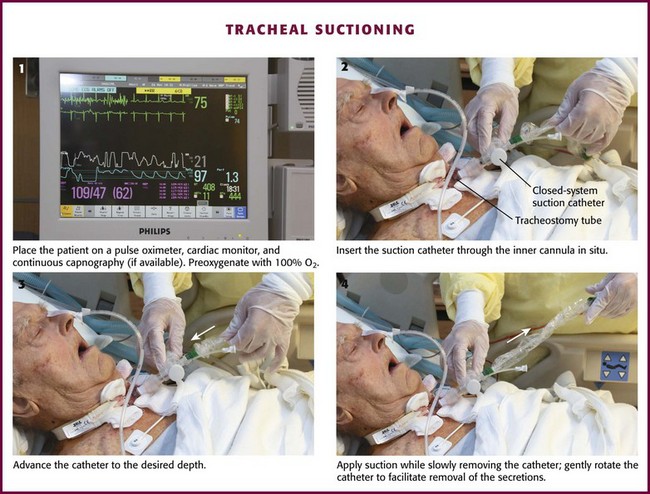

Before tracheal suctioning, continuous pulse oximetry, cardiac monitoring, and continuous capnography, if available, should be initiated (Fig. 7-6, step 1). Awake and alert patients should be sitting upright with their head in a neutral position. For mechanically ventilated patients, the head of the bed should be elevated to 30 degrees to improve respiratory mechanics. Aseptic technique should be used throughout all suctioning procedures to prevent the introduction of bacteria. Backup airway equipment should be readily available (see Fig. 7-2). Preoxygenate the patient for at least 30 to 60 seconds. For mechanically ventilated patients, increase the fraction of inspired oxygen (Fio2) to 100%. For nonventilated patients, provide 10 to 15 L of high-flow oxygen. Humidify the air before suctioning to reduce the viscosity of respiratory secretions. Routine instillation of normal saline has not been shown to provide regular clinical benefit and is no longer recommended.22,26

Figure 7-6 Tracheal suctioning.

Once the patient has been adequately preoxygenated, insert the suction catheter through the inner cannula in situ (Fig. 7-6, step 2). If the carina is irritated during deep suctioning, a vigorous cough reflex will be activated. After reaching the desired depth, withdraw the suction catheter 1 to 2 cm and then apply suction while slowly removing the catheter (Fig. 7-6, steps 3 and 4). Gently rotate the catheter as it is withdrawn to facilitate removal of secretions. The duration of suctioning should not exceed 10 to 15 seconds.27

Monitor the patient throughout the procedure for signs of cardiac dysrhythmia, hypoxia, or a rise in end-tidal CO2. Immediately stop suctioning if any of these signs develop (see “Complications of Suctioning”). If marked respiratory distress is presumed to be secondary to significant tracheal obstruction, continue with expeditious suctioning to remove the obstruction (see “Obstruction and Complications from Tube Changes”).

Complications of Suctioning

Hypoxemia from suctioning may cause increased ICP, dysrhythmias, or even death. In neonates, hypoxia during suctioning may contribute to spontaneous intracerebral hemorrhage.28 A number of factors contribute to suctioning-related hypoxia, including interruption of mechanical ventilation, aspiration of air from the respiratory tract, and suctioning-related atelectasis.29 Use in-line suction catheters for ventilator-dependent patients to allow continuous oxygen delivery and positive pressure ventilation. Select the catheter size carefully to reduce the evacuation of airway gases during suctioning and help prevent atelectasis. Limit the duration of suctioning to 10 to 15 seconds and perform no more than three passes in succession. Measurement of arterial oxygen saturation may not be sufficient to assess hypoxia after suctioning. Oxygen consumption increases during suctioning despite insignificant changes in oxygen saturation. This increase in oxygen consumption is more prevalent in patients who possess a vigorous cough, are agitated, or resist suctioning.30

Dysrhythmias associated with suctioning may be caused by hypoxia, increased myocardial oxygen consumption, vagal stimulation, hypoventilation, or catecholamine release. Vagal stimulation caused by suctioning can cause bradycardia and hypotension.31 Bradycardia in the setting of hypoxia potentiates ventricular dysrhythmias, including ventricular fibrillation. Nebulized or intravenous atropine is recommended for bradycardia and can be used as pretreatment in patients at risk for bradycardia, particularly infants. Digoxin enhances vagal activity and may potentiate the vagal stimulation of ET suctioning.32 Sympathetic stimulation may occur as a result of hypoxia, pain, or stress of the procedure. Pain medications, anxiolytics, and preparation of the patient for the procedure may blunt the sympathetic response. Suctioning should be stopped immediately if a dysrhythmia develops.

Increases in ICP during suctioning are well documented.33–35 ET suctioning can induce a strong cough reflex, which is thought to contribute to the increased ICP by raising intrathoracic pressure, reducing cerebral perfusion pressure, and increasing systemic blood pressure. In susceptible patients, increases in ICP can lead to devastating outcomes.28,34,36 If there is concern that increases in ICP could harm the patient, several preventive steps should be taken before initiating ET suctioning. The most important interventions are providing adequate sedation and maximizing oxygenation.20 Hyperventilation before and between passes of the suction catheter can transiently lower ICP by reducing systemic CO2.34 One minute before suctioning, hyperventilate the patient by increasing the respiratory rate to approximately 30 breaths/min. If not heavily sedated, most patients will cough vigorously when suctioned. Lidocaine can be instilled into the trachea to blunt the cough reflex, thereby preventing an increase in ICP. To anesthetize the trachea locally, instill 1.5 to 2.0 mg/kg of 2% lidocaine into the tracheal tube. After administering the medication, prepare the patient for suctioning by ensuring that sedation and oxygenation are adequate. After 10 minutes to allow the lidocaine to produce its local effect, begin tracheal suctioning. This method has been shown to prevent increases in ICP and changes in cerebral hemodynamics.37

Atelectasis can occur when airway gases are suctioned too rapidly. To reduce this complication, choose a suction catheter that is less than half the inner diameter of the tracheostomy tube and minimize the duration and suction pressure. Atelectasis can be minimized by using a closed suction system and providing positive end-expiratory pressure after suctioning.38 Hyperventilation should not be performed routinely to resolve suction-related atelectasis.29

Minitracheostomy Suctioning Procedure

The minitracheostomy (“minitrach”) was designed to improve tracheal hygiene in patients with intact cough reflexes, normal ventilatory function, and vocalization. The minitrach serves as a small port solely for suctioning secretions. Commonly, a 4-mm indwelling cuffless cannula is inserted through the cricothyroid membrane into the trachea. Patients who are suctioned through a minitrach are at lower risk for gagging and aspiration because they are able to maintain laryngeal and glottic function.39 The minitrach device is seldom used in children because they have smaller airway diameters.

Changing a Tracheostomy Tube

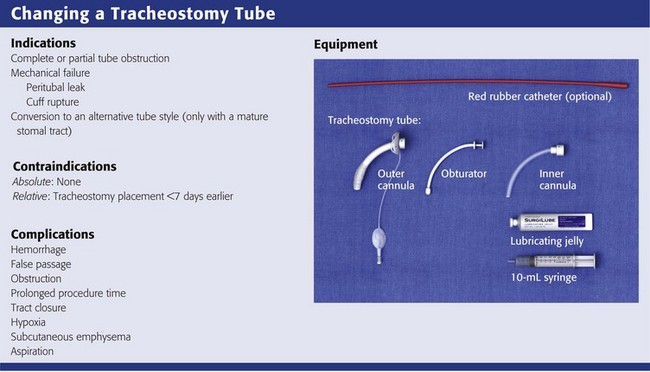

Indications

Maturation of the tracheostomy tract is generally completed by postoperative day 7.40 Most ED patients with a tracheostomy are seen after the stomal tract has matured, so routine changes of the tracheostomy tube can be done safely in the ED.41 Indications for exchange of the tracheostomy tube include cuff rupture or leak, leakage around the tube caused by tracheomalacia, other changes in tracheal anatomy, complete or partial tube occlusion, and conversion to an alternative tube style.42 There are no absolute contraindications to exchanging a tracheostomy tube in the ED as long as the stomal tract has matured. Before undertaking the exchange, consider whether further tissue trauma or hemorrhage might occur as a result of it42 or whether anatomic abnormalities could make the exchange difficult.

There is conflicting evidence on how frequently tracheostomy tubes should be changed.43 Do not perform tube changes on a predetermined schedule, but rather as the patient’s clinical condition dictates. There is some evidence that tubes left in place longer than 3 months are at higher risk for infection.44 Most manufacturers recommend that tracheostomy tubes be changed about 30 days after placement.

Equipment

When changing a tracheostomy tube, familiarize yourself with the resources and equipment available in the ED. Keep the equipment readily available, if not at the patient’s bedside. The necessary equipment is depicted in Figure 7-2.

Sizing

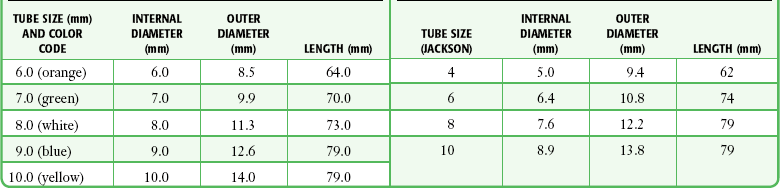

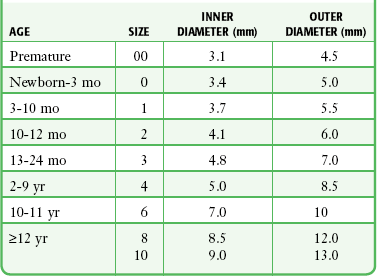

To determine the appropriate size of tube, consider the internal diameter (ID), outside diameter (OD), length, and curvature of the tube. The Chevalier Jackson sizing system indicates the length and tapering of the OD. This sizing method applies to metal tubes and most Shiley dual-cannula tracheostomy tubes. Table 7-1 lists common tracheostomy tubes and their dimensions. For dual-cannula tracheostomy tubes, the inner cannula has a 15-mm connection for a ventilator. Note that tracheostomy tubes with the same ID can have very different ODs and lengths. Consider the pretracheal distance before selecting a replacement tube of the appropriate size for obese patients (see “Special Populations”).

Table 7-1

Common Tracheostomy Tube Sizes with Dimensions

*Shiley also offers tracheostomy tubes with both distal and proximal (relative to the cuff) extended lengths for patients with large necks or other abnormal anatomy.

Adapted from Standards for the Care of Adult Patients with a Temporary Tracheostomy. London: The Intensive Care Society; 2008:53.

Single-cannula tracheostomy tubes are sized by the ID of the tube at its smallest dimension. The size of the tube is usually stamped on the flange. Before changing a tube, have the appropriate size of tube at the bedside along with tubes that are one or two sizes smaller. As a rule of thumb, most women can accommodate a tube with an OD of 10 mm, and most men can accommodate a tube with an OD of 11 mm.45 Table 7-1 lists the recommended sizes of tracheostomy tubes.

Components

Most tracheostomy tubes have three standard components: an outer cannula, an obturator, and an inner cannula (Fig. 7-3A). The outer cannula is the permanent portion of the tracheostomy tube and should not be removed unless complications arise or a tube change is needed. Attached to the outer cannula is a flange on either side with eyelets used to tether the tube to the patient’s neck. The obturator is a white rounded or cone-shaped object that is used to facilitate insertion of the tube. When inserted into the outer cannula, it extends several millimeters beyond the distal end of the tube.

Tracheostomy tubes can be cuffed or uncuffed. Cuffed tracheostomy tubes are used for patients on long-term mechanical ventilation and those at risk for aspiration. Cuffed tubes also prevent loss of volume during positive pressure ventilation while preventing air leaks across the vocal cords. As a result, speech is not possible for patients with a cuffed tube. Most tubes have a high-volume, low-pressure cuff that reduces mucosal injury and the risk for tracheal erosion or stenosis.46 Low-volume, low-pressure cuffs may be more effective in preventing aspiration.47,48 Inflate the tracheostomy cuff and deflate it by attaching a syringe to the Luer-Lok port at the proximal end of the pilot balloon and either injecting or removing approximately 10 mL of air. Determine cuff pressure by connecting the Luer-Lok port to a handheld manometer.

During weaning from tracheostomy, tracheal buttons can be used to maintain patency of the stoma in patients who do not require mechanical ventilation. They can be retained permanently if decannulation is not possible. Tracheal buttons have a hollow outer cannula and a solid inner cannula and extend from the outer skin into the tracheal lumen. Tracheal buttons can become displaced into the tracheal lumen if it is not tethered correctly and may become clogged with secretions.49 They may also have a speaking valve, such as the Passy-Muir (Passy-Muir, Inc., Irvine, CA) or the Shiley Phonate (Mallinckrodt Medical, St. Louis). These devices generally clip or twist onto the 15-mm coupling of the tracheostomy tube or inner cannula. Remove the speaking valve before changing the tracheostomy tube.

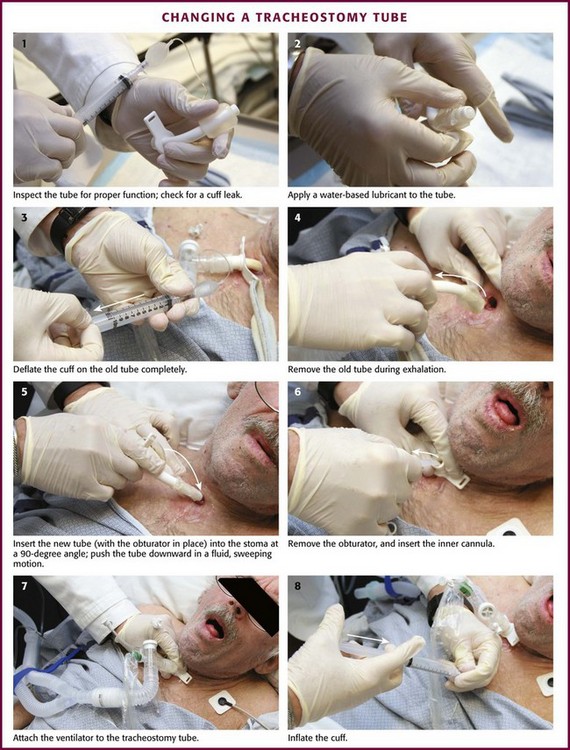

Procedure

As discussed previously, it is essential to ensure that all airway equipment is at the patient’s bedside before performing the tube exchange. In addition to having airway equipment ready, place the patient on continuous pulse oximetry, cardiac monitoring, and capnography, if available, to confirm tube placement. Identify the tracheostomy tube model and determine its size. Have this size and two other tubes that are one or two sizes smaller in the event that tube replacement is difficult. Inspect all equipment for proper function, including the replacement tube cuff for leaks and the obturator for ease of insertion and removal (Fig. 7-7, step 1). Coat the replacement tracheostomy tube with a water-based lubricant (Fig. 7-7, step 2).

The tracheostomy tube can be changed by either of two methods. If the tracheostomy tract is well matured, the tube can be exchanged with an obturator. To remove the old tracheostomy tube, first deflate the cuff completely (if present) (Fig. 7-7, step 3). Remove the existing tube with an “out-then-down” movement while the patient exhales (Fig. 7-7, step 4). Next, with the obturator in place, insert the new tube into the stoma at a 90-degree angle to the cervical axis (Fig. 7-7, step 5). If two experienced providers are available, one can be responsible for deflating the cuff and removing the old tube while the other inserts the new device.50 Next, gently push the tube downward in a fluid, sweeping motion so the external flange is flush against the neck. If necessary, use a tracheal hook to hold the stoma open. Remove the solid obturator immediately, insert the hollow internal cannula, inflate the cuff, return the patient’s head to the neutral position, and secure the external flange (Fig. 7-7, steps 6 to 8).

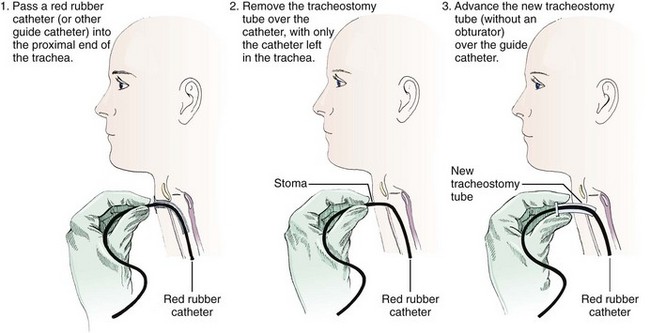

The second technique involves exchanging the tube with a modified Seldinger technique using a red rubber catheter, nasogastric tube, or a gum elastic bougie (Fig. 7-8).45,51 This technique is preferable if the tracheostomy tract is not well defined or if there is concern that tube exchange could be difficult. To exchange tubes with this method, first premeasure the distance needed to extend the guidewire device beyond the distal tip of the old tracheostomy tube. Advance the guide to the premeasured distance, deflate the cuff, and remove the tube as described previously. Next, without the obturator in place, advance the new device over the guide until it is seated securely in the trachea. Remove the guide and secure the new tube. Weinmann and Bander developed a modified Seldinger technique involving the use of an airway exchange catheter to allow jet or bag ventilation into the trachea during tube exchange. This adjunct delivers intratracheal oxygen and is helpful if hypoxemia is likely to occur.42

Confirm proper placement of the tube within the trachea with one of several possible techniques. Traditionally, the patient is ventilated and correct tube placement confirmed by observation of equal chest rise and auscultation of bilateral breath sounds. Although both signs are important to confirm correct placement, quantitative waveform capnography is now a class I American Heart Association recommendation for confirmation of ET intubation.52 It should be used for tracheostomy tube placement, if available. Multiple studies have shown quantitative capnography to be a highly sensitive tool for confirming correct placement of airway devices.53,54 Correct tube placement can also be confirmed by direct visualization of the tracheal rings with a fiberoptic scope.

Complications of Tracheostomy

Complications related to tracheostomy placement are common and sometimes life-threatening. This section addresses the emergency development of late postoperative complications (occurring more than 3 weeks after the operation). Patients with immediate and early postoperative complications are usually still hospitalized and are less likely to be seen in the ED.55 Late postoperative tracheostomy complications encountered in ED patients include obstruction, dislodgement, equipment failure, infection, anatomic disruption, and hemorrhage. Management of the patient varies depending on the type of complication that the patient is experiencing. Rapid recognition of the problem is paramount and can drastically affect the outcome.

Obstruction and Complications from Tube Changes

Obstruction of the tracheostomy tube is a common complication and can occur at the external opening of the tube, within the inner cannula, or at the distal end of the outer cannula. In one review, 30% of ED visits for respiratory distress were due to an obstructed tube.41 Obstruction is caused most commonly by dried respiratory secretions and, less often, by blood, aspirated material, or granulation tissue. The obstructing object may act as a ball valve and allow air to enter but restricts expiration.8 Such obstruction is easily remedied in the ED by removing the inner cannula and then cleaning and replacing it.

Interventions

Administer high-flow oxygen and encourage patients who can breathe spontaneously to cough. Manually remove any obstruction seen at the external tracheal tube opening. If there is no obvious external obstruction, remove the inner cannula and suction the secretions. Inspect the inner cannula and remove any obstructing objects. If the patient’s tracheostomy does not have an inner cannula, suction the tracheostomy tube to remove obstructing plugs. Thick secretions can be loosened in a critically ill patient by instilling normal saline into the tracheostomy tube, but this is no longer recommended for routine suctioning.26

Dislodgment

Displacement of the tracheal tube is a serious complication that can have a disastrous outcome if not recognized and corrected quickly. Patients at highest risk for poor outcomes from a dislodged tube are those who are obese, who have a recently inserted or changed tube, who have anatomic anomalies, and who are difficult to ventilate or were difficult to intubate in the past.56–58 Evidence of tube dislodgment is usually obvious. Signs and symptoms include hypoxemia, agitation, respiratory distress, altered mental status, subcutaneous emphysema, and high airway pressure. Dislodgement can occur during patient transfers, when traction is placed on the tube, or when the tube is manipulated for bag-valve-mask ventilation or ventilator tube connection. If a tracheostomy tube is too long, it can become dislodged inferiorly, which causes the tip to either abut the mucosal wall of the trachea or obstruct it at the level of the carina.

It is important to know when and why the tracheostomy was placed because such information will influence evaluation and management of the patient.59 If a tracheostomy tube becomes dislodged within the first 7 days after initial placement, the stoma can close rapidly and make reinsertion difficult. Blind, forceful attempts at reinsertion of the tracheostomy tube in the early postoperative period can result in the creation of a false passage and possible respiratory arrest. If accidental decannulation occurs before the tract has time to form, orotracheal intubation is the safest approach in the ED. Reinsertion of the tracheostomy tube is possible, but the patient will most likely require ET intubation to secure the airway.59 Patients with abnormal neck anatomy or other causes of a “difficult airway” may not benefit from reinsertion in the ED. In these cases, the procedure may need to be performed in the operating room. Seek emergency surgical consultation for complicated cases.

Preparation

As for all patients with tracheostomy complications, begin with a quick primary assessment and place the patient on appropriate monitoring devices. Continuous waveform capnography can be invaluable in determining whether the tracheostomy tube is placed properly. Absence of a waveform or end-tidal CO2 partial pressure less than 10 mm Hg is an indication that the airway device has become dislodged or was placed inappropriately.60 It is essential to have advanced airway equipment at the bedside, including two replacement tracheostomy tubes (each with an inner cannula). A fiberoptic bronchoscope, if available, can be helpful. Position the patient with the neck in extension to maximize alignment of the stoma and trachea. Neck flexion can cause downward displacement of the tube by as much as 3 to 4 cm.16

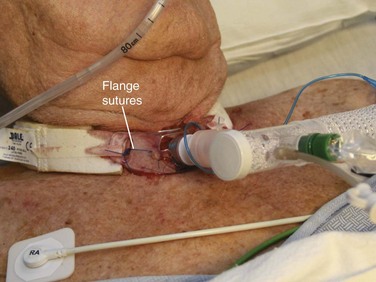

Interventions

If the tracheostomy stoma was created less than 7 days earlier, be prepared to orally intubate the patient. First, cut any flange sutures and remove the tracheostomy tube (Fig. 7-9). Stay sutures may be placed to hold the stoma open and better visualize the tracheal opening. If the patient is stable, attempt to reinsert the tracheostomy tube with the assistance of a gum elastic bougie or fiberoptic bronchoscope.45 If the patient is unstable with an obstructed tracheostomy tube, cut the flange sutures, remove the tube, and orally intubate the patient.

False Passage

A false lumen can be created during replacement of a tracheal tube or during repositioning of a dislodged tube. Obese patients are at high risk for false passage because of their redundant neck tissue (see “Special Populations”). Subcutaneous air, crepitus, or distortion of anterior neck landmarks may indicate placement of the tracheostomy tube into a false passage. Absence of a waveform on capnography confirms misplacement of the tracheostomy tube. Abdominal distention after bag-valve-mask ventilation may indicate placement of the tracheal tube through a tracheoesophageal fistula (TEF). If a false passage is suspected, remove and replace the tracheostomy tube expeditiously.

Equipment Failure

Tracheostomy tubes do not fracture frequently. When fractures do occur, they are most often located at the juncture of the flange and the tube connection.61,62 A fractured tube fragment may migrate inferiorly and obstruct the tracheal lumen. Patients may have acute respiratory complaints such as cough, dyspnea, choking, or wheezing. Prolonged retention of a foreign body can result in chronic respiratory symptoms such as wheezing, coughing, or recurrent bouts of pneumonia or bronchiectasis. To manage this problem, replace the tube if possible and consider bronchoscopy for retrieval of the tube fragment.63

Infection

Risk factors for systemic infection include impairment of host defenses and exposure to large numbers of bacteria that bypass the upper airway defense systems. In healthy patients, the upper respiratory tract is colonized by normal oropharyngeal flora. In tracheostomy patients, the normal flora can be replaced by virulent pathogens such as enteric gram-negative bacteria.64 The organisms most commonly cultured from tracheostomy stomas and tubes are Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Acinetobacter, and Staphylococcus aureus.65 Colonization rates are high in these patients, even in the absence of systemic infection. The tracheostomy tube bypasses the natural protective barriers of the upper airway. Suctioning a colonized tracheostomy tube can introduce bacteria into the lower respiratory tract. Underlying medical conditions, prolonged hospitalization, impaired host defense mechanisms, and poor nutrition all increase susceptibility to infection.

Ventilator-associated tracheobronchitis (VAT) is the result of colonization of the upper airway and can eventually progress to VAP.66 Patients with VAT have fever, production of purulent sputum, and positive respiratory cultures but no evidence of a new infiltrate on chest radiography.66 VAT is frequently caused by multidrug-resistant organisms. Therefore, when choosing antimicrobial therapy, consider recent hospitalizations, previous infections, recent antibiotic use, and the hospital’s antibiogram.

Tracheostomy patients on long-term ventilation are also at risk for VAP. These patients are similar to those with VAT, except that they have an infiltrate on chest radiography. A common cause of VAP is aspiration. Patients become predisposed to aspiration if they have altered neurologic function, have an abnormal swallowing mechanism, or are mechanically ventilated and kept in the supine position for a prolonged time. Some degree of aspiration occurs in 33% to 61% of all patients with tracheostomies.67,68 To reduce the risk for aspiration, keep patients requiring mechanical ventilation in a semirecumbent position. It is generally recommended that 30 to 45 degrees is adequate to reduce the risk for VAP.69–71

Stomal infections and cellulitis are also common.41 The bacteria cultured most frequently from patients with tracheostomy-related cellulitis are S. aureus, Pseudomonas species, and Monilia. Consider Candida albicans infection in patients previously treated with antibiotics and those who have an underlying immunocompromised state. Peristomal cellulitis can usually be treated with good wound care and oral antibiotics. The most dangerous complications from cellulitis are mediastinitis, mediastinal abscess, necrotizing fasciitis, and paratracheal abscess. Consider these complications in patients who have pain with breathing, pain with swallowing, or signs of systemic infection. Strongly consider a deep neck infection in diabetic patients.72 β-Hemolytic streptococci or coagulase-positive staphylococci are the cause in 90% of patients with craniocervical necrotizing fasciitis.73 Sputum samples, obtained via tracheal suctioning, should be analyzed when infectious complications are suspected. Radiologic studies, namely, a chest radiograph, cervical computed tomography (CT), and chest CT, should be ordered as indicated.

Antimicrobial treatment in the ED should cover the most common organisms for the suspected site of tracheostomy-related infection. Broad-spectrum systemic antimicrobials, along with adjuvant aerosol therapy, should be given urgently to high-risk patients.74 Depending on the patient’s condition, surgical evaluation may be needed.41

Tracheal Stenosis and Tracheomalacia

Tracheal stenosis and tracheomalacia are late complications of a tracheostomy, often occurring weeks to months after decannulation. Its overall incidence is unknown, but clinically significant stenosis has been estimated to develop in 10% of all tracheostomy patients.75 Tracheal stenosis occurs most often at the level of the stoma but can develop proximal (suprastomal) or distal to the stoma as a result of a poorly fitting tube or cuff. Pressure on the tracheal lumen from the tube or cuff can cause epithelial destruction, tracheitis, ulceration, persistent inflammation, and subsequent stenosis. Stenosis at the stoma can occur from rigid tube systems with excessive motion and pressure points.16 Symptoms become evident when the tracheal diameter is narrowed by 50% to 60%.76 Stridor typically occurs when the tracheal lumen is narrower than 5 mm.16 Respiratory symptoms such as cough, retained secretions, and progressive dyspnea with exertion are indications of clinically significant stenosis.

Tracheomalacia is weakening of the tracheal cartilage from pressure necrosis and results in luminal widening. A loose tracheostomy tube with excessive mobility can cause air leaks or tracheal collapse (Fig. 7-10). Patients with significant tracheomalacia experience tracheal collapse on expiration. This can result in air trapping and retained respiratory secretions. Pediatric patients are less able to tolerate cartilaginous weakening and tracheomalacia.

Interventions

Relief of respiratory compromise is problematic because a high-grade stenosis may make ET intubation difficult or impossible. To treat a patient with respiratory distress secondary to tracheal stenosis, first attempt to improve ventilation by elevating the head of the bed and placing the patient on high-flow humidified oxygen. Nebulized bronchodilators or racemic epinephrine may also be helpful. Keep a cricothyrotomy kit readily available in the event that ET intubation is impossible. Tracheal stenosis can be diagnosed definitively by laryngoscopy and flexible fiberoscopy.41 Other imaging modalities, such as CT, are not sensitive enough to detect stenosis. Treatment of tracheal stenosis involves operative dilation or resection of granulomatous tissue in the operating room.

Tracheoesophageal Fistula

TEF is an uncommon, late complication of tracheostomy. It occurs in 1% of tracheostomy patients as a result of injury to the posterior tracheal wall.77 Early TEF can occur if a puncture wound or small laceration is made in the anterior esophageal wall during placement of the tracheostomy. The most common cause of a TEF is a poorly fitted tracheostomy tube or an overinflated cuff.77 Injury to the esophageal mucosa from a nasogastric or orogastric tube can also cause a TEF.

Interventions

Once a TEF is diagnosed, the immediate goal should be to reduce the amount of tracheal and pulmonary soilage by inflating a cuff below the level of the fistula. If the current tracheostomy tube is not long enough to allow placement of a cuff distal to the TEF, exchange it with a longer tracheostomy tube or an ET tube. An orogastric or nasogastric tube can also be inserted to prevent gastric contents from further contaminating the respiratory tract. Early consultation with an otolaryngologist or thoracic surgeon is appropriate because the definitive treatment is surgical.77 TEF is not usually an immediately life-threatening complication, and tube exchange can be performed in conjunction with the surgical team.

Bleeding

Major bleeding is one of the most feared complications of tracheostomy. A history of bleeding or minor bleeding that has stopped spontaneously cannot automatically be attributed to minor irritation or skin erosion. It may not be possible to fully evaluate bleeding from a tracheostomy site in the ED without consultation or specialized equipment such as a fiberoptic endoscope. Sources of bleeding include the thyroid vessels, anterior jugular veins, brachiocephalic (innominate) artery, carotid artery, and aortic arch.78,79 Bleeding from esophageal or gastric sources may occur if a TEF is present or if the patient has aspirated blood. Erosion of a major vessel from the cuff or tip of the tube is responsible for 10% of all tracheostomy hemorrhages and is a devastating complication. The IA is the vessel most commonly involved.80

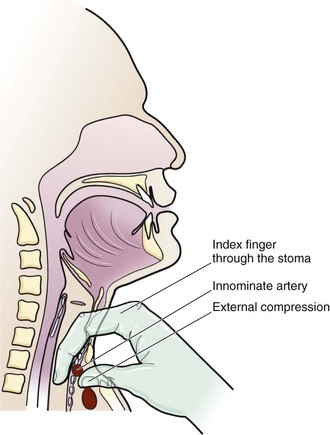

A tracheoinnominate artery fistula (TIF) is a late complication of tracheostomy that usually occurs within the first 4 weeks after insertion, but it can happen at any time.12,81 The mortality rate associated with a TIF approaches 100%.82 The anatomic proximity of the IA to the trachea places it at higher risk for fistulization if the tracheal wall is injured. The vessel crosses from left to right as it moves superiorly and lies immediately anterior to the trachea at the level of the superior thoracic inlet. Risk factors for TIF include placement of the stoma below the third tracheal ring, caudal migration of the tracheal tube, and the presence of a cephalad-coursing IA.

A single episode of hemoptysis or tracheal bleeding may be the only warning sign of a TIF. Any amount of bleeding or hemoptysis exceeding 10 mL within 48 hours after placement of the tube should be considered a “sentinel bleed” and an indication that a fatal hemorrhage may be imminent. Some patients report only a new cough or retrosternal pain.83 Presume that a history or evidence of 10 mL or more of blood is from an arterial source.

Preparation: When evaluating a patient with a suspected TIF, place advanced airway equipment at the bedside. Emergency surgical consultation is mandatory. Position the patient with the head of the bed elevated and the neck in slight extension. Secure adequate intravenous access, and prepare the patient to go to the operating room. In addition to the equipment noted in Figure 7-2, have a scalpel with a No. 10 or 11 blade and a 50-mL syringe at the bedside.

Interventions: If the patient is stable, attempt to visualize the bleeding site. Look for the IA in the anterior tracheal wall at or below the sternal notch. If significant tracheal bleeding is present, hyperinflate the tracheostomy tube cuff with the 50-mL syringe to compress the artery against the posterior sternal wall. Inflate the balloon slowly to prevent rupture of the cuff. Depending on the make and model of the tube, inflating the cuff with the entire 50 mL may not be possible. If a TIF has been caused by cuff erosion, this procedure should tamponade the bleeding. If the patient’s tracheostomy tube does not have a cuff, replace it with a cuffed ET or tracheostomy tube.

Position the cuff of the ET tube below the stoma at the level of the upper part of the sternum and hyperinflate it. If the patient continues to bleed despite this maneuver, apply digital pressure through the tracheal stoma to compress the anterior tracheal wall against the sternum. Digital pressure is considered the most reliable technique to stop hemorrhage and can provide control of bleeding during transport to the operating room (Fig. 7-11).41 Extension of the stoma with a vertical incision to the jugular notch may be necessary if the provider cannot reach the TIF through the original stoma.

Minor Bleeding

Preparation: Prepare patients with minor tracheostomy bleeding in the same way that you would those with major bleeding. Gather the appropriate airway equipment at the bedside. In addition to the standard equipment shown in Figure 7-2, obtain the following:

Interventions: For external or stomal bleeding, begin with local irrigation to find the source of the bleeding. Most incisional or stomal bleeding can be stopped by applying direct pressure for 3 to 5 minutes. Application of absorbable hemostatic material may improve the outcome of direct pressure application. If an external bleeding site continues to ooze, consider adjunctive treatment. Options include injecting 0.5 to 1.0 mL of lidocaine with epinephrine near the source, placing a single suture for hemostasis, or using cauterization. Last, replace the tracheostomy tube. Following tube replacement, suction carefully to confirm resolution of the bleeding and to identify secondary sources of bleeding.

Transesophageal Puncture for Voice Restoration

Complications

Operative and immediate postoperative complications of TEP are infrequent.84 Long-term complications include stomal stenosis, aspiration of the prosthesis, fistula leakage, TEP necrosis, and swallowing impairment. Reported infectious complications associated with TEP include deep neck abscess, aspiration pneumonia, and cervical cellulitis.85

The emergency care provider should be aware of the most common complications, few of which are life-threatening. Accumulation of thick or inspissated secretions or food above the TEP can cause upper airway obstruction. Prosthesis dislodgment, occlusion, or erosion secondary to infection should be considered in all patients with acute changes in voice production or decreased ability to speak.86 Esophageal edema causing dysphagia and loss of TEP speech has been reported and should be differentiated from other causes of esophageal obstruction.86

Transtracheal Oxygen Delivery Systems

Low-flow oxygen is prescribed for patients who have adequate ventilatory function but chronic hypoxia. Many patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, pulmonary fibrosis, sleep apnea, lung cancer, and α1-antitrypsin deficiency are candidates for outpatient use of supplemental oxygen.87–89 Traditionally, supplemental oxygen has been delivered by nasal cannula. Although nasal cannula oxygenation is easy to administer, it has several side effects, including drying of the nasal mucosa, epistaxis, ear discomfort, contact dermatitis from the oxygen tubing, and dry throat.87,89 Use of a nasal cannula is inefficient because it delivers oxygen only during inspiration and the oxygen must traverse the anatomic dead space of the nares and hypopharynx.

Transtracheal oxygen (TTO) delivery systems enhance the efficiency of oxygenation by administering oxygen directly to the lower respiratory tract. These systems reduce complications, improve patient comfort, and increase compliance.90 Oxygen is delivered through all phases of the respiratory cycle and directly into the trachea, thereby bypassing dead spaces in the upper airway.88 As a result, the required oxygen flow rate is commonly reduced by at least 50%.90 Gas mixture in the distal end of the trachea is more effective in eliminating CO2. Clinically, TTO systems usually reduce the patient’s work of breathing and exertional dyspnea.89 Physiologic benefits include reduced erythrocytosis, decreased pulmonary vascular resistance, improved cor pulmonale, improved arterial oxygen tension, and increased exercise capacity.91

TTO catheters are small tubes that deliver oxygen directly to the lumen of the trachea. The catheter is held in place by a subcutaneous tract, and the catheter is inserted into the lower part of the trachea. Low-flow oxygen (2 to 10 L/min) is supplied directly to the trachea by a narrow (7- to 11-Fr) catheter. Typically, an 11-cm catheter sits in the trachea with its tip 1 to 2 cm above the carina.89 It can have a single or multiple distal ports for oxygen flow. The catheter is held in place by a thin band or necklace through two openings in the flange.

The surgical procedure is often done in an outpatient setting with the patient under local anesthesia. Initially, a small stent is placed percutaneously into the anterior aspect of the neck; it is then replaced with a TTO catheter in 1 to 2 weeks after the tract matures.89 Dislodgment of the catheter during this time can result in closure of the tract within a matter of minutes. Once the tracheocutaneous fistula has epithelialized, the catheter may be inserted. Early catheter changes should be done in the clinician’s office via a modified Seldinger technique if the integrity of the stoma is questionable. After the tract has fully matured, most patients can change their catheter at home.

Early complications (developing within 3 weeks after the procedure) occur in approximately 30% of patients and include bleeding, infection, pneumothorax, costochondritis, and dislodgement (which can be caused by coughing).87,92 Pneumomediastinum and sudden death have been reported as possible, yet rare complications.93 Late complications occur in about 40% of patients and include mucus plugging, bleeding, infection, and hemoptysis.91 A mucus ball is an accumulation of inspissated mucus that adheres to the outer surface of the TTO catheter tip. It can cause coughing, wheezing, and dyspnea. Life-threatening airway obstruction resulting from the formation of a large mucus ball has been reported.94

Interventions

Manage minor bleeding at the catheter site with gauze packing or cauterization. If significant bleeding is identified or suspected, consult a specialist on an emergency basis and manage the airway definitively as clinically indicated (see the section ”Major Bleeding”). Manage skin and pulmonary infections with the techniques discussed for tracheostomy care.

Stents

Tracheal stenosis and tracheomalacia are known complications of artificial airways. Management options include surgery and placement of silicone stents in the trachea. Patients who have had their tracheostomy tubes successfully decannulated may need stents if symptomatic stenosis or tracheomalacia occurs. Indications for and complications of tracheal stents are beyond the scope of this chapter, but the clinician should be aware of the possibility that these indwelling devices may be present in patients who have undergone head and neck surgery or previous tracheostomies.57,95

Transtracheal Needle Aspiration

Transtracheal needle aspiration was first described in the late 1950s as a means of obtaining sterile sputum for culture from patients with recurrent pneumonia or lower respiratory tract infections. In theory, the risk of sample contamination is reduced by introducing a collection device beyond the oropharynx. This procedure has largely fallen out of favor with many clinicians because of patient noncompliance, the risk for complications, and the belief that the procedure is unnecessary.96 Alternative sampling methods such as bronchoalveolar lavage have become more widely accepted and used. At present, transtracheal needle aspiration is no longer recommended97 and should not be performed in the ED.

Special Populations

The prevalence of obesity (body mass index [BMI] ≥30) and morbid obesity (BMI ≥40) has increased dramatically over the past few decades.98,99 Obesity increases the patient’s risk for cardiovascular and metabolic comorbidity, and obese patients have a higher risk for ventilatory dysfunction secondary to altered respiratory mechanics.100 Lung compliance, functional residual capacity, and expiratory reserve volume in an obese patient are reduced exponentially in relation to BMI.101,102 As weight increases, vital capacity and total lung capacity decrease.101 Ultimately, obese patients have decreased pulmonary reserve, which can cause a rapid onset of hypoxia if they become critically ill.

Morbidly obese patients are particularly at risk for life-threatening complications related to tracheostomy.103 Tube obstruction and accidental dislodgement appear to be more common in obese patients. Dislodgement is specifically associated with increased rates of morbidity and mortality.58 Delayed recognition of tube dislodgment because of abnormal neck anatomy accounts for nearly 30% of tracheostomy-related deaths in the obese population.58,103

Preparation

For the management of an obese patient with a tracheostomy-related complaint, it is important to have all advanced airway equipment at the bedside (Fig. 7-2). In addition to standard equipment, attempt to obtain an extra long or adjustable-flange tracheostomy tube to span the elongated pretracheal distance that is common in morbidly obese patients.104 In obese patients, standard tracheostomy tubes may be too short proximal to the cuff and have a higher risk for malposition.

In addition to standard monitoring, use continuous capnography, if available, to prevent delay in the recognition of tube dislodgement.58 Physical signs, such as reduced breath sounds and subcutaneous air, may be more difficult to recognize in obese patients. Fiberoptic bronchoscopy may be needed to confirm correct tube placement. The patient should be positioned with the neck in slight extension, and the head of the bed should be elevated to approximately 30 degrees.

Interventions

Approach an obese patient with the same protocols outlined previously in this chapter for the applicable complication. If the tube is obstructed, deflation of the tracheostomy cuff may not be sufficient to allow adequate ventilation because external compression caused by abnormal neck anatomy may occur. If tube dislodgement is suspected, ET intubation may be preferred over blind reinsertion because of the increased risk for false passage.103 Tube placement can be confirmed with direct visualization via fiberoptic bronchoscopy.

Pediatrics

Most considerations for pediatric patients follow adult guidelines and are discussed in the appropriate sections of this chapter, but some specific considerations should be mentioned. The tracheostomy-related mortality rate in pediatric patients ranges from 0.5% to 6%.105 The main causes of death are accidental dislodgement and obstruction of the tracheostomy tube.106 Complication rates are highest in patients requiring tracheostomy for airway obstruction. In comparison, patients with central nervous system disorders, respiratory distress syndrome, and congenital heart disorders are less likely to experience complications.24

Equipment

When replacing a tracheostomy tube in a child, always have at least two tracheostomy tubes available: the current size and a size smaller. Pediatric tubes generally have a much smaller diameter than adult tracheostomy tubes, and many of them do not have an inner cannula. Pediatric tracheostomy tubes rarely have inflatable cuffs, except for those used for certain special indications.107 Suction catheters, a bag-valve-mask device, ET tubes, resuscitation medication, and equipment appropriate for the pediatric population should be available when treating pediatric tracheostomy patients. Continuous capnography may detect certain tracheostomy complications and is recommended.108

Sizing

Pediatric tracheostomy tubes share most of the same components of the tubes used in adults. The ID of the tube is stamped on the outer cannula flange, and that information should guide the clinician’s choice of replacement tubes. Recommended tube sizes according to age are listed in Table 7-2. Age guidelines can be helpful, but they may not be reliable in pediatric patients because of complex medical problems. Premature infants may be small for their age and weight, thus making estimation of tube size even more difficult.

Table 7-2

Tracheostomy Tube Sizes Based on Patient Age

Adapted from Mullins JB, Templer JW, Kong J, et al: Airway resistance and work of breathing in tracheostomy tubes. Laryngoscope. 1993;103:1367.

Cuff

Cuff pressure recommendations for pediatric patients are less than 20 cm H2O.109 With few exceptions, low-pressure, high-volume cuffs should be used.24

Suctioning

Suctioning recommendations in pediatric patients clearly support the use of a premeasured suction catheter to reduce the rate of mucosal irritation and to limit the development of granulation tissue. The premeasured technique uses an exact depth of insertion, which reduces epithelial damage if the catheter is inserted too deeply and inadequate suctioning if the catheter is not inserted deeply enough. Depth of insertion can be estimated by measuring a similar tube before inserting the suction catheter. In children with fenestrated tracheostomy tubes, suction catheters may accidentally go through the fenestrations and cause mucosal irritation. If this happens repeatedly, granulation tissue may develop at the site.24

Complications

Pediatric tracheostomy complications are similar to those in the adult population. Their incidence is estimated to be between 5% and 49%.105 Late complications most likely to be seen in the ED include obstruction, dislodgement, bleeding, pneumothorax, infection, pneumomediastinum, TEF, and TIF. Chronic respiratory complications include tracheomalacia, tracheal stenosis, vocal cord paralysis, and vocal cord fusion.

Pneumomediastinum and pneumothorax are generally thought to be early complications of tracheostomy, but they should always be considered in a pediatric tracheostomy patient. In children, the pleural apices rise higher than in adults and can even extend into the lower part of the neck. These complications can be caused by a dislodged tube positioned in a false passage or a malpositioned tube that causes an increase in intrathoracic pressure.106

The most common bacterial species that colonize pediatric tracheostomies are P. aeruginosa and S. aureus. As in adults, colonization does not require treatment unless signs of acute infection are present.106 Suprastomal collapse of the anterior tracheal wall is very common in pediatric patients and can cause air trapping. A tracheostomy tube that places excessive pressure on the tracheal rings will cause inflammation, chondritis, and weakening of the cartilaginous rings. Significant collapse can hamper subsequent decannulation success.

References

1. Heffner, JE, Miller, KS, Sahn, SA. Tracheostomy in the intensive care unit. Part 1: indications, technique, management. Chest. 1986;90:269.

2. Groves, DS, Durbin, CG, Jr. Tracheostomy in the critically ill: indications, timing and techniques. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2007;13:90.

3. Esteban, A, Anzueto, A, Alia, I, et al. How is mechanical ventilation employed in the intensive care unit? An international utilization review. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:1450.

4. Lewarski, JS. Long-term care of the patient with a tracheostomy. Respir Care. 2005;50:534.

5. Garrubba, M, Turner, T, Grieveson, C. Multidisciplinary care for tracheostomy patients: a systematic review. Crit Care. 2009;13:R177.

6. Unroe, M, Kahn, JM, Carson, SS, et al. One-year trajectories of care and resource utilization for recipients of prolonged mechanical ventilation: a cohort study. Ann Intern Med. 2010;153:167.

7. Oliver, ER, Gist, A, Gillespie, MB. Percutaneous versus surgical tracheotomy: an updated meta-analysis. Laryngoscope. 2007;117:1570.

8. Tayal, VS. Tracheostomies. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 1994;12:707.

9. Chew, JY, Cantrell, RW. Tracheostomy. Complications and their management. Arch Otolaryngol. 1972;96:538.

10. Bonanno, FG. Techniques for emergency tracheostomy. Injury. 2008;39:375.

11. Fowler, S, Knapp-Spooner, C, Donohue, D. The ABC’s of tracheostomy care. J Pract Nurs. 1995;45:44.

12. Epstein, SK. Anatomy and physiology of tracheostomy. Respir Care. 2005;50:476.

13. Toews, G. Host defense. In: Albert RK, Spiro SG, Jett JR, eds. Comprehensive Respiratory Medicine. St. Louis: Mosby; 1999:1.5.1.

14. Tamburri, LM. Care of the patient with a tracheostomy. Orthop Nurs. 2000;19:49.

15. Minsley, MA, Wrenn, S. Long-term care of the tracheostomy patient from an outpatient nursing perspective. ORL Head Neck Nurs. 1996;14:18.

16. Lewis, RJ. Tracheostomies. Indications, timing, and complications. Clin Chest Med. 1992;13:137.

17. Vyas, D, Inweregbu, K, Pittard, A. Measurement of tracheal tube cuff pressure in critical care. Anaesthesia. 2002;57:275.

18. Lewis, RM. Airway clearance techniques for the patient with an artificial airway. Respir Care. 2002;47:808.

19. Van de Leur, JP, Zwaveling, JH, Loef, BG, et al. Endotracheal suctioning versus minimally invasive airway suctioning in intubated patients: a prospective randomised controlled trial. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:426.

20. Gemma, M, Tommasino, C, Cerri, M, et al. Intracranial effects of endotracheal suctioning in the acute phase of head injury. J Neurosurg Anesthesiol. 2002;14:50.

21. Johnson, KL, Kearney, PA, Johnson, SB, et al. Closed versus open endotracheal suctioning: costs and physiologic consequences. Crit Care Med. 1994;22:658.

22. AARC clinical practice guideline. Nasotracheal suctioning. American Association for Respiratory Care. Respir Care. 1992;37:898.

23. Vanner, R, Bick, E. Tracheal pressures during open suctioning. Anaesthesia. 2008;63:313.

24. Sherman, JM, Davis, S, Albamonte-Petrick, S, et al. Care of the child with a chronic tracheostomy. This official statement of the American Thoracic Society was adopted by the ATS Board of Directors, July 1999. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2000;161:297.

25. Spence, K, Gillies, D, Waterworth, L. Deep versus shallow suction of endotracheal tubes in ventilated neonates and young infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2003. [CD003309].

26. Ackerman, MH, Mick, DJ. Instillation of normal saline before suctioning in patients with pulmonary infections: a prospective randomized controlled trial. Am J Crit Care. 1998;7:261.

27. Tenaillon, A, Boiteau, R, Perrin-Gachadoat, D, et al. [Humidification and aspiration of the respiratory tract in patients with mechanical ventilation.]. Rev Prat. 1990;40:2315.

28. Shah, AR, Kurth, CD, Gwiazdowski, SG, et al. Fluctuations in cerebral oxygenation and blood volume during endotracheal suctioning in premature infants. J Pediatr. 1992;120:769.

29. AARC Clinical Practice Guidelines. Endotracheal suctioning of mechanically ventilated patients with artificial airways 2010. Respir Care. 2010;55:758.

30. Walsh, JM, Vanderwarf, C, Hoscheit, D, et al. Unsuspected hemodynamic alterations during endotracheal suctioning. Chest. 1989;95:162.

31. Day, T, Farnell, S, Wilson-Barnett, J. Suctioning: a review of current research recommendations. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 2002;18:79.

32. Fiorentini, A. Potential hazards of tracheobronchial suctioning. Intensive Crit Care Nurs. 1992;8:217.

33. Rudy, EB, Turner, BS, Baun, M, et al. Endotracheal suctioning in adults with head injury. Heart Lung. 1991;20:667.

34. Kerr, ME, Weber, BB, Sereika, SM, et al. Effect of endotracheal suctioning on cerebral oxygenation in traumatic brain-injured patients. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:2776.

35. Durand, M, Sangha, B, Cabal, LA, et al. Cardiopulmonary and intracranial pressure changes related to endotracheal suctioning in preterm infants. Crit Care Med. 1989;17:506.

36. Crosby, LJ, Parsons, LC. Cerebrovascular response of closed head-injured patients to a standardized endotracheal tube suctioning and manual hyperventilation procedure. J Neurosci Nurs. 1992;24:40.

37. Bilotta, F, Branca, G, Lam, A, et al. Endotracheal lidocaine in preventing endotracheal suctioning-induced changes in cerebral hemodynamics in patients with severe head trauma. Neurocrit Care. 2008;8:241.

38. Maggiore, SM, Lellouche, F, Pigeot, J, et al. Prevention of endotracheal suctioning–induced alveolar derecruitment in acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2003;167:1215.

39. Callaghan, SP, Doremus, KA, Wilson, DJ, et al. Minitracheostomy: an alternative to “blind” endotracheal suctioning. Dimens Crit Care Nurs. 1994;13:38.

40. Wright, SE, VanDahm, K. Long-term care of the tracheostomy patient. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:473.

41. Hackeling, T, Triana, R, Ma, OJ, et al. Emergency care of patients with tracheostomies: a 7-year review. Am J Emerg Med. 1998;16:681.

42. Weinmann, M, Bander, JJ. Introduction of a new tracheostomy exchange device after percutaneous tracheostomy in a patient with coagulopathy. J Trauma. 1996;40:317.

43. White, AC, Kher, S, O’Connor, HH. When to change a tracheostomy tube. Respir Care. 2010;55:1069.

44. Backman, S, Bjorling, G, Johansson, UB, et al. Material wear of polymeric tracheostomy tubes: a six-month study. Laryngoscope. 2009;119:657.

45. Standards for the Care of Adult Patients with a Temporary Tracheostomy. London: The Intensive Care Society, 2008. [53].

46. Stauffer, JL, Olson, DE, Petty, TL. Complications and consequences of endotracheal intubation and tracheotomy. A prospective study of 150 critically ill adult patients. Am J Med. 1981;70:65.

47. Dhand, R, Johnson, JC. Care of the chronic tracheostomy. Respir Care. 2006;51:984.

48. Young, PJ, Pakeerathan, S, Blunt, MC, et al. A low-volume, low-pressure tracheal tube cuff reduces pulmonary aspiration. Crit Care Med. 2006;34:632.

49. Godwin, JE, Heffner, JE. Special critical care considerations in tracheostomy management. Clin Chest Med. 1991;12:573.

50. Posner, JC, Cronan, K, Badaki, O, et al. Emergency care of the technology-assisted child. Clin Pediatr Emerg Med. 2006;7:38.

51. Young, JS, Brady, WJ, Kesser, B, et al. A novel method for replacement of the dislodged tracheostomy tube: the nasogastric tube “guidewire” technique. J Emerg Med. 1996;14:205.

52. Neumar, RW, Otto, CW, Link, MS, et al. Part 8: adult advanced cardiovascular life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S729.

53. Grmec, S. Comparison of three different methods to confirm tracheal tube placement in emergency intubation. Intensive Care Med. 2002;28:701.

54. Silvestri, S, Ralls, GA, Krauss, B, et al. The effectiveness of out-of-hospital use of continuous end-tidal carbon dioxide monitoring on the rate of unrecognized misplaced intubation within a regional emergency medical services system. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;45:497.

55. Engoren, M, Arslanian-Engoren, C, Fenn-Buderer, N. Hospital and long-term outcome after tracheostomy for respiratory failure. Chest. 2004;125:220.

56. Engels, PT, Bagshaw, SM, Meier, M, et al. Tracheostomy: from insertion to decannulation. Can J Surg. 2009;52:427.

57. Wahidi, MM, Ernst, A. Role of the interventional pulmonologist in the intensive care unit. J Intensive Care Med. 2005;20:141.

58. Cook, TM, Woodall, N, Harper, J, et al. Major complications of airway management in the UK: results of the Fourth National Audit Project of the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Difficult Airway Society. Part 2: intensive care and emergency departments. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:632.

59. O’Connor, HH, White, AC. Tracheostomy decannulation. Respir Care. 2010;55:1076.

60. Anderson, CT, Breen, PH. Carbon dioxide kinetics and capnography during critical care. Crit Care. 2000;4:207.

61. Okafor, BC. Fracture of tracheostomy tubes. Pathogenesis and prevention. J Laryngol Otol. 1983;97:771.

62. Piromchai, P, Lertchanaruengrit, P, Vatanasapt, P, et al. Fractured metallic tracheostomy tube in a child: a case report and review of the literature. J Med Case Reports. 2010;4:234.

63. Slotnick, DB, Urken, ML, Sacks, SH, et al. Fracture, separation, and aspiration of tracheostomy tubes: management with a new technique. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1987;97:423.

64. Park, DR. The microbiology of ventilator-associated pneumonia. Respir Care. 2005;50:742.

65. Harlid, R, Andersson, G, Frostell, CG, et al. Respiratory tract colonization and infection in patients with chronic tracheostomy. A one-year study in patients living at home. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1996;154:124.

66. Nseir, S, Ader, F, Marquette, CH. Nosocomial tracheobronchitis. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2009;22:148.

67. Leder, SB. Incidence and type of aspiration in acute care patients requiring mechanical ventilation via a new tracheotomy. Chest. 2002;122:1721.

68. Sharma, OP, Oswanski, MF, Singer, D, et al. Swallowing disorders in trauma patients: impact of tracheostomy. Am Surg. 2007;73:1117.

69. Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital-acquired, ventilator-associated, and healthcare-associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388.

70. Muscedere, J, Dodek, P, Keenan, S, et al. Comprehensive evidence-based clinical practice guidelines for ventilator-associated pneumonia: prevention. J Crit Care. 2008;23:126.

71. Niel-Weise, BS, Gastmeier, P, Kola, A, et al. An evidence-based recommendation on bed head elevation for mechanically ventilated patients. Crit Care. 2011;15:R111.

72. Huang, TT, Liu, TC, Chen, PR, et al. Deep neck infection: analysis of 185 cases. Head Neck. 2004;26:854.

73. Bahu, SJ, Shibuya, TY, Meleca, RJ, et al. Craniocervical necrotizing fasciitis: an 11-year experience. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;125:245.

74. Ahmed, QA, Niederman, MS. Respiratory infection in the chronically critically ill patient. Ventilator-associated pneumonia and tracheobronchitis. Clin Chest Med. 2001;22:71.

75. Norwood, S, Vallina, VL, Short, K, et al. Incidence of tracheal stenosis and other late complications after percutaneous tracheostomy. Ann Surg. 2000;232:233.

76. Sue, RD, Susanto, I. Long-term complications of artificial airways. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:457.

77. Reed, MF, Mathisen, DJ. Tracheoesophageal fistula. Chest Surg Clin North Am. 2003;13:271.

78. Brantigan, CO. Delayed major vessel hemorrhage following tracheostomy. J Trauma. 1973;13:235.

79. Peres, LC, Mamede, RC, de Mello Filho, FV. Rupture of the aorta due to a malpositioned tracheal cannula in a 4-month-old baby. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 1996;34:175.

80. Jones, JW, Reynolds, M, Hewitt, RL, et al. Tracheo-innominate artery erosion: successful surgical management of a devastating complication. Ann Surg. 1976;184:194.

81. Scalise, P, Prunk, SR, Healy, D, et al. The incidence of tracheoarterial fistula in patients with chronic tracheostomy tubes: a retrospective study of 544 patients in a long-term care facility. Chest. 2005;128:3906.

82. Goldenberg, D, Ari, EG, Golz, A, et al. Tracheotomy complications: a retrospective study of 1130 cases. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123:495.

83. Carson, L, Stransky, R. A 75-year-old woman with tracheostomy site bleeding. J Emerg Nurs. 1994;20:79.

84. Geraghty, JA, Wenig, BL, Smith, BE, et al. Long-term follow-up of tracheoesophageal puncture results. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1996;105:501.

85. Laccourreye, O, Menard, M, Crevier-Buchman, L, et al. In situ lifetime, causes for replacement, and complications of the Provox voice prosthesis. Laryngoscope. 1997;107:527.

86. Wang, RC, Bui, T, Sauris, E, et al. Long-term problems in patients with tracheoesophageal puncture. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1991;117:1273.

87. Orvidas, LJ, Kasperbauer, JL, Staats, BA, et al. Long-term clinical experience with transtracheal oxygen catheters. Mayo Clin Proc. 1998;73:739.

88. Series, F, Forge, JL, Lampron, N, et al. Transtracheal air in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea hypopnoea syndrome. Thorax. 2000;55:86.

89. Eckmann, DM. Transtracheal oxygen delivery. Crit Care Clin. 2000;16:463.

90. Kampelmacher, MJ, Deenstra, M, van Kesteren, RG, et al. Transtracheal oxygen therapy: an effective and safe alternative to nasal oxygen administration. Eur Respir J. 1997;10:828.

91. Christopher, KL. Transtracheal oxygen catheters. Clin Chest Med. 2003;24:489.

92. Sampablo, I, Escarrabill, J, Rosell, A, et al. Transtracheal catheter acceptance and adverse events in long-term home oxygen therapy. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 1998;53:123.

93. Kristo, DA, Turner, JF, Hugler, R. Transtracheal oxygen catheterization with pneumomediastinum and sudden death. Chest. 1996;110:844.

94. Christopher, KL, Schwartz, MD. Transtracheal oxygen therapy. Chest. 2011;139:435.

95. Majid, A, Fernandez, L, Fernandez-Bussy, S, et al. Tracheobronchomalacia. Arch Bronconeumol. 2010;46:196.

96. Bartlett, JG. Diagnostic tests for agents of community-acquired pneumonia. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(suppl 4):S296.

97. Irwin, RS, Rippe, JM. Manual of Intensive Care Medicine. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins; 2009.

98. Sturm, R. Increases in morbid obesity in the USA: 2000-2005. Public Health. 2007;121:492.

99. Parikh, NI, Pencina, MJ, Wang, TJ, et al. Increasing trends in incidence of overweight and obesity over 5 decades. Am J Med. 2007;120:242.

100. Rabec, C, de Lucas Ramos, P, Veale, D. Respiratory complications of obesity. Arch Bronconeumol. 2011;47:252.

101. Jones, RL, Nzekwu, MM. The effects of body mass index on lung volumes. Chest. 2006;130:827.

102. Salome, CM, King, GG, Berend, N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108:206.

103. El Solh, AA, Jaafar, W. A comparative study of the complications of surgical tracheostomy in morbidly obese critically ill patients. Crit Care. 2007;11:R3.

104. Whittle, AT, Marshall, I, Mortimore, IL, et al. Neck soft tissue and fat distribution: comparison between normal men and women by magnetic resonance imaging. Thorax. 1999;54:323.

105. Fraga, JC, Souza, JC, Kruel, J. Pediatric tracheostomy. J Pediatr (Rio J). 2009;85:97.

106. Cochrane, LA, Bailey, CM. Surgical aspects of tracheostomy in children. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2006;7:169.

107. Deutsch, ES. Tracheostomy: pediatric considerations. Respir Care. 2010;55:1082.

108. Kleinman, ME, Chameides, L, Schexnayder, SM, et al. Part 14: pediatric advanced life support: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation and Emergency Cardiovascular Care. Circulation. 2010;122:S876.

109. Weiss, M, Dullenkopf, A, Fischer, JE, et al. Prospective randomized controlled multi-centre trial of cuffed or uncuffed endotracheal tubes in small children. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:867.