Chapter 14 Tracheal Intubation and Airway Management

9 Explain how to evaluate elevated work of breathing as an indication for tracheal intubation

Normally, the respiratory muscles account for less than 5% of the total body oxygen consumption. In patients with respiratory failure, this can increase to as much as 40%. It can be difficult to assess the work of breathing by clinical examination. However, patients who have rapid shallow breathing, use of accessory respiratory muscles, or paradoxic respirations have a predictably high work of breathing. The results of an arterial blood gas analysis (i.e., pH, PCO2, and PO2) may be initially normal in such patients. Eventually, the respiratory muscles fatigue and fail, causing inadequate oxygenation and ventilation. Mechanical ventilation can sometimes be done without tracheal intubation (see Chapter 9) but is more reliably accomplished with intubation.

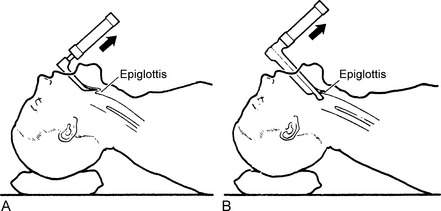

15 How is direct laryngoscopy accomplished?

The technique varies slightly depending on the type of blade used (Figs. 14-1 and 14-2). First, the head is placed in the sniffing position with cervical spine in flexion and atlantooccipital joint in extension. The blade is inserted into the right side of the mouth. Then the tongue is moved to the left. With a curved (Macintosh) blade, the tip is inserted between the base of the tongue and the superior surface of the epiglottis, an area called the vallecula. If a straight (Miller or Wisconsin) blade is used, the tip is manipulated to lift the epiglottis. With both blade types, once the tip is in position, the blade is moved forward and upward to expose the larynx. An endotracheal tube is then inserted into the trachea. Gentle downward pressure on the thyroid cartilage may help to improve the view of the larynx.

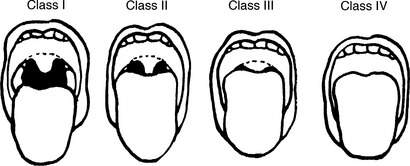

19 How do you evaluate mouth opening and pharyngeal space to predict difficult intubation?

In the adult, a mouth opening of two to three fingerbreadths is usually adequate. One measure of pharyngeal space is the Mallampati class (Fig. 14-3). The patient is asked to sit upright with the head in a neutral position. Then he or she is asked to open the mouth as widely as possible and protrude the tongue as far as possible. The classification is based on the pharyngeal structures seen.

24 What are the immediate, short-term complications of tracheal intubation?

Key Points Airway management in patients in the intensive care unit

1. In most patients, it is possible to maintain a patent airway without tracheal intubation.

2. Before managing a patient’s airway, confirm the availability and function of all equipment that may be used.

3. The five main indications for tracheal intubation are upper airway obstruction, inadequate oxygenation, inadequate ventilation, elevated work of breathing, and airway protection.

4. To predict a difficult intubation, evaluate four anatomic features on physical examination: mouth opening, pharyngeal space, neck extension, and submandibular compliance.

5. Confirm endotracheal tube placement immediately with a reliable method such as carbon dioxide capnography.

1 American Society of Anesthesiologists: Practice guidelines for management of the difficult airway: http://ecommerce.asahq.org/p-177-practice-guidelines-for-management-of-the-difficult-airway.aspx. Accessed October 13, 2011

2 Berg R.A., Hemphill R., Abella B.S., et al. Part 5: adult basic life support: 2010 American Heart Association guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122:S685–S705.

3 El-Orbany M., Connolly L.A. Rapid sequence induction and intubation: current controversy. Anesth Analg. 2010;110:1318–1325.

4 Henderson J. Airway management in the adult. In: Miller R.D., ed. Miller’s Anesthesia. 7th ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2010:1573–1610.