CHAPTER 37 TRACHEAL AND TRACHEOBRONCHIAL TREE INJURIES

For most of history, acute tracheobronchial injuries have been considered uniformly fatal. In 1871, Winslow observed a healed left mainstem bronchus in a canvasback duck that was taken while hunting. This showed that the animal had survived the rupture and demonstrated the potential of the airways for healing. In 1927, Krinitzki reported the first long-term human survivor. Autopsy findings of a 31-year-old woman, who had been injured at age 10 years when a keg of wine fell on her chest, suggested that humans with tracheobronchial disruption may have the same healing potential as the canvasback duck. The autopsy demonstrated a completely occluded right mainstem bronchus. In the modern era, understanding of anatomy, injury mechanisms, and surgical repair technique has led to improved outcomes in the face of such injuries. Although tracheobronchial injuries still may be lethal, most are treatable. A high index of suspicion is required to make a timely diagnosis and to provide appropriate intervention, both of which are essential if the patient is to have the best opportunity for recovery.

DIAGNOSIS

Presentation

Some retrospective reports show that up to two thirds of these intrathoracic tracheobronchial tears will go unrecognized longer than 24 hours and up to 10% of tracheobronchial tears will not produce any initial clinical or radiological signs and are recognized months later after stricture occurs. Immediate intubation of patients with multisystem trauma can mask laryngeal or high cervical tracheal injuries and contribute to a delay in the diagnosis. After tracheobronchial transection, the peribronchial connective tissues may remain intact and allow continued ventilation of the distal lung analogous to the way perfusion is maintained after traumatic aortic transection. If unrecognized, this injury heals with scarring and granulation tissue and may possibly create bronchial stenosis or obstruction such as in the duck reported by Winslow. After a latent period, granulation tissue and stricture of the bronchus will develop. Distal to the stricture, pneumonia, bronchiectasis, abscesses, and even empyema can result. Complete obstruction without infection leads to prolonged atelectasis and diminished pulmonary function.

Evaluation

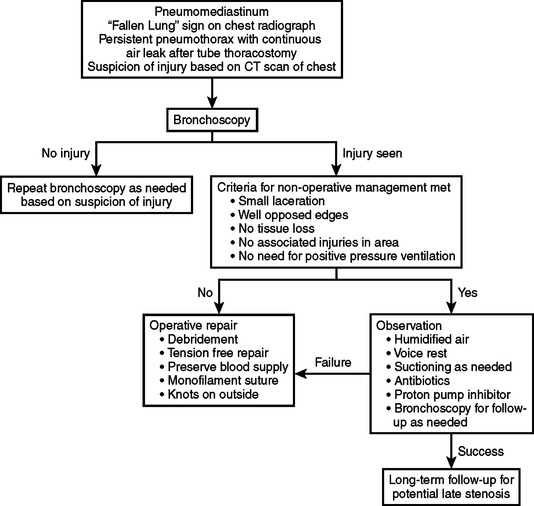

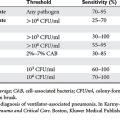

Diagnosis should be suspected based on the clinical history and the constellation of signs and symptoms previously listed. Evaluation of the patient with a suspected injury to the tracheobronchial tree is shown in the algorithm in Figure 1. The advent of spiral computed tomography (CT) has created interest in evaluation of injury with this technique. Three-dimensional reconstruction has been used to elegantly demonstrate the site and extent of injuries in case reports. While tracheobronchial injury may be well demonstrated on CT in some cases, there is no evidence that CT is adequate to exclude an injury and obviate the need for diagnostic bronchoscopy. CT scans suggesting injury should prompt bronchoscopy for definitive diagnosis. In addition to visualization of possible tracheal injury on CT, indications for bronchoscopy include large pneumomediastinum, refractory pneumothorax, large air leak, persistent atelectasis, or, occasionally, marked subcutaneous emphysema. Bronchoscopy, whether rigid or flexible, is the best-studied means of establishing the diagnosis and determining the site, nature, and extent of the tracheobronchial disruption. A potential disadvantage of rigid bronchoscopy is that it requires general anesthesia, as well as a stable ligamentous and bony cervical spine. A rigid scope has the advantage of direct visualization and the ability to provide ventilation. Flexible bronchoscopy may be performed without general anesthesia, and offers the potential for controlled insertion of a nasal or orotracheal tube while maintaining cervical stabilization. The most critical determinant seems to be the experience and comfort level of the endoscopist. It has been shown that, in the hands of an experienced bronchoscopist, either technique can be performed with a high degree of accuracy. Lesions may be missed initially or their severity may be underestimated. These lesions may evolve into more obvious or severe injuries, and for this reason bronchoscopy should be liberally repeated as needed.

MANAGEMENT

Initial Management

Tracheostomy performed in the operating room is advocated by many as the safest and securest way to obtain airway control. This may be done in the awake patient to avoid airway loss in those with adequate airway protection. If the trachea is completely transected, the distal trachea can usually be found in the superior mediastinum and grasped for insertion of a cuffed tube. The approach taken must vary with the resources and expertise available at each institution. One must also be aware that even though the airway is secured, the injury may still be exacerbated with mechanical ventilation if the injury is distal to the tube. Tube thoracostomies should be appropriately placed at this time and connected to suction. After the airway is controlled, there is time for an orderly identification of concurrent injuries, performance of interventions such as esophagoscopy, laryngoscopy, arteriography, celiotomy as necessary, and transport to definitive care areas. Guidelines for the management of tracheobronchial injuries are given in Figure 1.

Operative Management

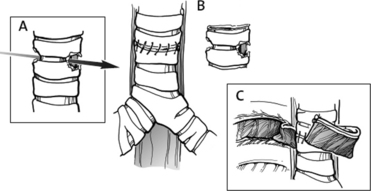

Optimal repair includes adequate debridement of devitalized tissue, including cartilage, and primary end-to-end anastomosis of the clean tracheal or bronchial ends. This anastomosis can be accomplished free of tension by mobilizing anteriorly and posteriorly, thereby preserving the lateral blood supply. Tension may also be released with cervical flexion. This may be maintained postoperatively by securing the chin to the chest with a suture. Many investigators have recommended completion of the anastomosis with interrupted absorbable suture. We have found, however, that the use of a running, continuous, absorbable monofilament suture offers a secure repair and better visibility during construction of the anastomosis. The membranous portion may be repaired without tension and then brought together as the cartilaginous portion is begun. Sutures may be placed around or through the cartilage but must ensure approximation of mucosa to mucosa. Tying the suture knots on the outside of the lumen helps prevent suture granulomata and subsequent stricture. To prevent subsequent leak and fistula formation, the suture line may be reinforced with a patch of pericardium, a vascularized pedicle from the pleura, intercostal muscle, strap muscles, omentum, or vascularized pleura in late repairs to protect the repair and to aid in bronchial healing. During early repairs, the pleura is flimsy and usually not suitable as reinforcement. The vascularized pedicle of intercostal muscle offers both better protection and added healing potential for the repair. For this reason, the intercostal muscle should routinely be preserved during thoracotomy with the corresponding vein, artery, and nerve. This is accomplished by entering the chest through the bed of the rib. The rib may be preserved or sacrificed. An incision is made directly over the rib and the periosteum stripped off. At the superior border of the rib, the incision is carried through the posterior layer of the periosteum to enter the pleural space. The intercostal muscle is then divided from the ribs above and below and used as a flap to be wrapped around and tacked to the trachea. In this manner, viable tissue is placed between the repair and surrounding vital structures and blood supply in the area of the repair is increased, facilitating healing (Figure 2).

Angood PB, Attia EL, Brown RA, Mulder DS. Extrinsic civilian trauma to the larynx and cervical trachea—important predictors of long-term morbidity. J Trauma. 1986;26:869.

Asensio JA, Valenziano CP, Falcone RE, Grosh JD. Management of penetrating neck injuries: the controversy surrounding zone II injuries. Surg Clin North Am. 1991;71(2):267.

Cornwell EE, Kennedy F, Ayad IA, et al. Transmediastinal gunshot wounds: a reconsideration of the role of aortography. Arch Surg. 1996;131:949.

Demetriades D, Theodorou D, Cronwell E, Asensio J. Transcervical gunshot injuries: mandatory operation is not necessary. J Trauma. 1996;40:758.

Dowd NP, Clarkson K, Walsh MA. Delayed bronchial stenosis after blunt chest trauma. Anesth Analg. 1996;82:1078.

Edwards WH, Morris HA, DeLozier JB, Adkins RB. Airway injuries—the first priority in trauma. Am Surg. 1987;53(4):192.

Flynn AE, Thomas AN, Schecter WP. Acute tracheobronchial injury. J Trauma. 1989;29:1326.

Grewal H, Rao PM, Mukerji S, Ivatury RR. Management of penetrating laryngotracheal injuries. Head Neck. 1995;17:494.

Griffith JL. Fracture of the bronchus. Thorax. 1949;4:105.

Kaiser AC, O’Brien SM, Detterbeck FC. Blunt tracheobronchial injuries treatment and outcomes. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;71(6):2059-2065.

Mills SA, Hudspeth AS, Myers RT. Clinical spectrum of blunt tracheobronchial disruption illustrated by seven cases. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1982;84:49.

Minard G, Kudsk KA, Croce MA, et al. Laryngotracheal trauma. Am Surg. 1992;58:181.

Noyes L, McSwain NE, Markowitz IP. Penendoscopy with arteriography versus mandatory exploration of penetrating wounds of neck. Ann Surg. 1986;204:21.

Oh KS, Fleischner EG, Wyman SM. Characteristic pulmonary finding in traumatic complete transection of a main-stem bronchus. Radiology. 1969;92:371.

Sands DE L, Ledgerwood AM, Lucas CE. Pneumomediastinum on a surgical service. Am Surg. 1988;54:434.

Spencer JA, Rogers CE, Westaby S. Clinico-radiological correlates in rupture of the major airways. Clin Radiol. 1991;43:371.

Symbas PN, Justicz AG, Ricketts RR. Rupture of the airways from blunt trauma: treatment of complex injuries. Ann Thorac Surg. 1992;54:177.

Winslow WH. Rupture of bronchus from wild duck. Philadelphia Medical Times. 1871:255.