Chapter 282 Toxoplasmosis (Toxoplasma gondii)

Etiology

Newly infected cats and other Felidae species excrete infectious Toxoplasma oocysts in their feces. Toxoplasma organisms are transmitted to cats by ingestion of infected meat containing encysted bradyzoites or by ingestion of oocysts excreted by other recently infected cats. The parasites then multiply through schizogonic and gametogonic cycles in the distal ileal epithelium of the cat intestine. Oocysts containing 2 sporocysts are excreted, and, under proper conditions of temperature and moisture, each sporocyst matures into 4 sporozoites. For about 2 wk the cat excretes 105-107 oocysts/day, which may retain their viability for >1 yr in a suitable environment. Oocysts sporulate 1-5 days after excretion and are then infectious. Oocysts are killed by drying or boiling but not exposure to bleach. Oocysts have been isolated from soil and sand frequented by cats, and outbreaks associated with contaminated water have been reported. Oocysts and tissue cysts are sources of animal and human infections (Fig. 282-1). There are 3 clonal and atypical types of T. gondii that have different virulence for mice (and perhaps for humans) and form different numbers of cysts in the brains of outbred mice.

Clinical Manifestations

Acquired Toxoplasmosis

Immunocompetent children who acquire infection postnatally generally do not have clinically recognizable symptoms. When clinical manifestations are apparent, they may include almost any combination of fever, stiff neck, myalgia, arthralgia, maculopapular rash that spares the palms and soles, localized or generalized lymphadenopathy, hepatomegaly, hepatitis, reactive lymphocytosis, meningitis, brain abscess, encephalitis, confusion, malaise, pneumonia, polymyositis, pericarditis, pericardial effusion, and myocarditis. Chorioretinitis is usually unilateral and occurs in approximately 1% of cases in the USA. Half the cases of ocular toxoplasmosis in English children are due to acute acquired infection; the appearance does not distinguish acute vs. congenital infection. Symptoms may be present for a few days only or may persist many months. The most common manifestation is enlargement of 1 or a few cervical lymph nodes. Cases of Toxoplasma lymphadenopathy rarely resemble infectious mononucleosis, Hodgkin’s disease, or other lymphadenopathies (Chapter 484). In the pectoral area in older girls and women, enlarged nodes may be confused with breast neoplasms. Mediastinal, mesenteric, and retroperitoneal lymph nodes may be involved. Involvement of intra-abdominal lymph nodes may be associated with fever, mimicking appendicitis. Nodes may be tender but do not suppurate. Lymphadenopathy may wax and wane for as long as 1-2 yr.

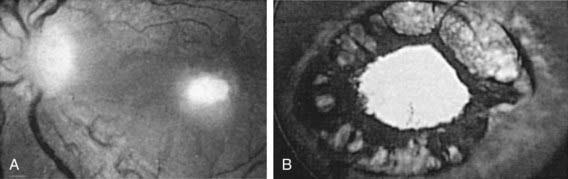

Ocular Toxoplasmosis

In the USA and Western Europe, T. gondii is estimated to cause 35% of cases of chorioretinitis (Fig. 282-2). In Brazil, T. gondii retinal lesions are common. Clinical manifestations include blurred vision, visual floaters, photophobia, epiphora, and, with macular involvement, loss of central vision. Ocular findings of congenital toxoplasmosis also include strabismus, microphthalmia, microcornea, cataracts, anisometropia, nystagmus, glaucoma, optic neuritis, and optic atrophy. Episodic recurrences are common, but precipitating factors have not been defined.

Congenital Toxoplasmosis

The spectrum and frequency of neonatal manifestations of 210 newborns with congenital Toxoplasma infection identified by a serologic screening program of pregnant women are presented in Table 282-1. In this study, 10% had severe congenital toxoplasmosis with CNS involvement, eye lesions, and general systemic manifestations; 34% had mild involvement with normal clinical examination results other than retinal scars or isolated intracranial calcifications; and 55% had no detectable manifestations. These numbers represent an underestimation of the incidence of severe congenital infection for several reasons: the most severe cases, including most of those individuals who died, were not referred; therapeutic abortion was often performed when acute acquired infection of the mother was diagnosed early during pregnancy; in utero spiramycin therapy may have diminished the severity of infection; and only 13 infants had brain CT and 23% did not have a CSF examination. Routine newborn examinations often yield normal findings for congenitally infected infants, but more careful evaluations may reveal significant abnormalities. In 1 study of 28 infants identified by a universal state-mandated serologic screening program for T. gondii–specific IgM, 26 had normal findings on routine newborn examination and 14 had significant abnormalities detected with more careful evaluation. The abnormalities included retinal scars (7 infants), active chorioretinitis (3 infants), and CNS abnormalities (8 infants). In Fiocruz, Belo Horizonte, Brazil, infection is common, occurring in 1/600 live births. Half of these infected infants have active chorioretinitis at birth.

Table 282-1 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS IN 210 INFANTS WITH PROVED CONGENITAL TOXOPLASMA INFECTION*

| FINDING | NO. EXAMINED | NO. POSITIVE (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Prematurity | 210 | |

| Birthweight <2,500 g | 8 (3.8) | |

| Birthweight 2,500-3,000 g | 5 (7.1) | |

| Intrauterine growth retardation | 13 (6.2) | |

| Icterus | 201 | 20 (10) |

| Hepatosplenomegaly | 210 | 9 (4.2) |

| Thrombocytopenic purpura | 210 | 3 (1.4) |

| Abnormal blood count (anemia, eosinophilia) | 102 | 9 (4.4) |

| Microcephaly | 210 | 11 (5.2) |

| Hydrocephaly | 210 | 8 (3.8) |

| Hypotonia | 210 | 12 (5.7) |

| Convulsions | 210 | 8 (3.8) |

| Psychomotor retardation | 210 | 11 (5.2) |

| Intracranial calcification x-ray | 210 | 24 (11.4) |

| Ultrasound | 49 | 5 (10) |

| Computed tomography | 13 | 11 (84) |

| Abnormal electroencephalogram | 191 | 16 (8.3) |

| Abnormal cerebrospinal fluid | 163 | 56 (34.2) |

| Microphthalmia | 210 | 6 (2.8) |

| Strabismus | 210 | 111 (5.2) |

| Chorioretinitis | 210 | |

| Unilateral | 34 (16.1) | |

| Bilateral | 12 (5.7) |

* Infants were identified by prospective study of infants born to women who acquired Toxoplasma gondii infection during pregnancy.

Data adapted from Couvreur J, Desmonts G, Tournier G, et al: A homogeneous series of 210 cases of congenital toxoplasmosis in 0 to 11-month-old infants detected prospectively, Ann Pediatr (Paris) 31:815–819, 1984.

There is also a wide spectrum of symptoms of untreated congenital toxoplasmosis that presents later in the 1st yr of life (Table 282-2). More than 80% of these children have IQ scores of <70, and many have convulsions and severely impaired vision.

Table 282-2 SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS OCCURRING BEFORE DIAGNOSIS OR DURING THE COURSE OF UNTREATED ACUTE CONGENITAL TOXOPLASMOSIS IN 152 INFANTS (A) AND IN 101 OF THESE SAME CHILDREN AFTER THEY HAD BEEN FOLLOWED 4 YR OR MORE (B)

| SIGNS AND SYMPTOMS | FREQUENCY OF OCCURRENCE IN PATIENTS WITH | |

|---|---|---|

| “Neurologic” Disease* | “Generalized” Disease† | |

| A. INFANTS | 108 PATIENTS (%) | 44 PATIENTS (%) |

| Chorioretinitis | 102 (94) | 29 (66) |

| Abnormal cerebrospinal fluid | 59 (55) | 37 (84) |

| Anemia | 55 (51) | 34 (77) |

| Convulsions | 54 (50) | 8 (18) |

| Intracranial calcification | 54 (50) | 2 (4) |

| Jaundice | 31 (29) | 35 (80) |

| Hydrocephalus | 30 (28) | 0 (0) |

| Fever | 27 (25) | 34 (77) |

| Splenomegaly | 23 (21) | 40 (90) |

| Lymphadenopathy | 18 (17) | 30 (68) |

| Hepatomegaly | 18 (17) | 34 (77) |

| Vomiting | 17 (16) | 21 (48) |

| Microcephalus | 14 (13) | 0 (0) |

| Diarrhea | 7 (6) | 11 (25) |

| Cataracts | 5 (5) | 0 (0) |

| Eosinophilia | 6 (4) | 8 (18) |

| Abnormal bleeding | 3 (3) | 8 (18) |

| Hypothermia | 2 (2) | 9 (20) |

| Glaucoma | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Optic atrophy | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Microphthalmia | 2 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Rash | 1 (1) | 11 (25) |

| Pneumonitis | 0 (0) | 18 (41) |

| B. CHILDREN ≥4 YR OF AGE | 70 PATIENTS (%) | 31 PATIENTS (%) |

| Mental retardation | 62 (89) | 25 (81) |

| Convulsions | 58 (83) | 24 (77) |

| Spasticity and palsies | 53 (76) | 18 (58) |

| Severely impaired vision | 48 (69) | 13 (42) |

| Hydrocephalus or microcephalus | 31 (44) | 2 (6) |

| Deafness | 12 (17) | 3 (10) |

| Normal | 6 (9) | 5 (16) |

* Patients with otherwise undiagnosed central nervous system disease in the 1st yr of life.

† Patients with otherwise undiagnosed non-neurologic diseases during the 1st 2 mo of life.

Adapted from Eichenwald H: A study of congenital toxoplasmosis. In Slim JC, editor: Human toxoplasmosis, Copenhagen, 1960, Munksgaard, pp 41–49. Study performed in 1947. The most severely involved institutionalized patients were not included in the later study of 101 children.

Systemic Signs

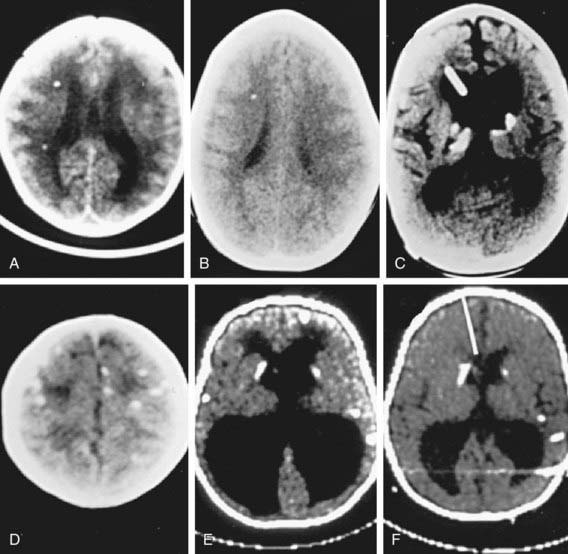

Central Nervous System

CSF abnormalities occur in at least 30% of infants with congenital toxoplasmosis. A CSF protein level of >1 g/dL is characteristic of severe CNS toxoplasmosis and is usually accompanied by hydrocephalus. Local production of T. gondii–specific IgG and IgM antibodies may be demonstrated. CT of the brain is useful to detect calcifications, determine ventricular size, and demonstrate porencephalic cystic structures (Fig. 282-3). Calcifications occur throughout the brain, but there is a propensity for development of calcifications in the caudate nucleus and basal ganglia, choroid plexus, and subependyma. MRI and contrast-enhanced CT brain scans are useful for detecting active inflammatory lesions. MRIs that take only a brief time (<45 sec) for imaging or ultrasonography may be useful for following ventricular size. Treatment in utero and in the 1st yr of life results in improved neurologic outcomes.

Eyes

Almost all untreated congenitally infected infants develop chorioretinal lesions by adulthood, and about 50% will have severe visual impairment. T. gondii causes a focal necrotizing retinitis in congenitally infected individuals (see Fig. 282-2). Retinal detachment may occur. Any part of the retina may be involved, either unilaterally or bilaterally, including the maculae. The optic nerve may be involved, and toxoplasmic lesions that involve projections of the visual pathways in the brain or the visual cortex also may lead to visual impairment. In association with retinal lesions and vitritis, the anterior uvea may be intensely inflamed, leading to erythema of the external eye. Other ocular findings include cells and protein in the anterior chamber, large keratic precipitates, posterior synechiae, nodules on the iris, and neovascular formation on the surface of the iris, sometimes with increased intraocular pressure and glaucoma. The extraocular musculature may also be involved directly. Other manifestations include strabismus, nystagmus, visual impairment, and microphthalmia. Enucleation has been required for a blind, phthisic, painful eye. The differential diagnosis of ocular toxoplasmosis includes congenital coloboma and inflammatory lesions caused by cytomegalovirus, Treponema pallidum, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, or vasculitis. Ocular toxoplasmosis may be a recurrent and progressive disease that requires multiple courses of therapy. Limited data suggest that occurrence of lesions in the early years of life may be prevented by instituting antimicrobial treatment with pyrimethamine and sulfonamides during the 1st yr of life and that treatment of the infected fetus in utero followed by treatment in the 1st yr of life with pyrimethamine, sulfadiazine, and leukovorin reduces the incidence and the severity of the retinal disease.

Diagnosis

Treatment

Prevention

Counseling pregnant women about the methods of preventing transmission of T. gondii (see Fig. 282-1) during pregnancy can reduce acquisition of infection during gestation. Women who do not have specific antibody to T. gondii before pregnancy should only eat well-cooked meat during pregnancy and avoid contact with oocysts excreted by cats. Cats that are kept indoors, maintained on prepared food, and not fed fresh, uncooked meat should not contact encysted T. gondii or shed oocysts. Serologic screening, ultrasound monitoring, and treatment of pregnant women during gestation can also reduce the incidence and manifestations of congenital toxoplasmosis. No protective vaccine is available.

Arun V, Noble AG, Latkany P, et al. Cataracts in congenital toxoplasmosis. J AAPOS. 2007;11:551-554.

Benevento JD, Jager RD, Noble AG, et al. Toxoplasmosis-associated neovascular lesions treated successfully with ranibizumab and antiparasitic therapy. Arch Ophthalmol. 2008;124:1152-1156.

Berrebi A, Bardou M, Bessieres MH, et al. Outcome for children infected with congenital toxoplasmosis in the first trimester and with normal ultrasound findings: a study of 36 cases. Eur J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;135:53-57.

Boyer K, Holfels E, Roizen N, et al. Risk factors for Toxoplasma gondii infection in mothers of infants with congenital toxoplasmosis: implications for prenatal management and screening. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:564-571.

Brezin AP, Thulliez P, Couvreur J, et al. Ophthalmic outcomes after prenatal and postnatal treatment of congenital toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 2003;135(6):779-784.

Burnett AJ, Shortt SG, Isaac-Renton J, et al. Multiple cases of acquired toxoplasmosis retinitis presenting in an outbreak. Ophthalmology. 1998;105:1032-1037.

Carme B, Demar M, Ajzenberg D, et al. Severe acquired toxoplasmosis caused by wild cycle of Toxoplasma gondii, French Guiana. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:656-658.

Daffos F, Forestier F, Capella-Pavlovsky M, et al. Prenatal management of 746 pregnancies at risk for congenital toxoplasmosis. N Engl J Med. 1988;318:271-275.

Demar M, Ajzenberg D, Maubon D, et al. Fatal outbreak of human toxoplasmosis along the Maroni River: epidemiological, clinical, and parasitological aspects. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;45:e88-e95.

Desmonts G, Couvreur J. Natural history of congenital toxoplasmosis. Ann Pediatr. 1984;31:799-802.

Elbez-Rubinstein A, Ajzenberg D, Darde ML, et al. Congenital toxoplasmosis and reinfection during pregnancy: case report, strain characterization, experimental model of reinfection, and review. J Infect Dis. 2009;199:280-285.

Foulon W, Villena E, Stray-Pedersen B, et al. Treatment of toxoplasmosis during pregnancy: a multicenter study of impact on fetal transmission and children’s sequelae at age 1 year. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;180:410-415.

Gilbert RE, Freeman K, Lago EG, et al. Ocular sequelae of congenital toxoplasmosis in Brazil compared with Europe. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2:e277.

Jamieson SE, De Roubaix LA, Cortina-Borja M, et al. Genetic and epigenetic factors at COL1A1 and ABCA4 influence clinical outcome in congenital toxoplasmosis. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2285.

Jones JL, Dubey JP. Waterborne toxoplasmosis—recent developments. Exp Parasitol. 2010;124:10-25.

Kieffer F, Wallon M, Garcia P, et al. Risk factors for retinochoroiditis during the first 2 years of life in infants with treated congenital toxoplasmosis. Pediatr Infect Dis. 2008;27:27-32.

Kodjikian L, Wallon M, Fleury J, et al. Ocular manifestations in congenital toxoplasmosis. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2006;244:14-21.

Lehmann T, Marcet PL, Graham DH, et al. Globalization and the population structure of Toxoplasma gondii. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11423-11428.

Liesenfeld O, Montoya JG, Kenney S, et al. Effect of testing for IgG avidity in the diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection in pregnant women: experience in a US reference laboratory. J Infect Dis. 2001;183:1248-1253.

McAuley J, Boyer K, Patel D, et al. Early and longitudinal evaluations of treated infants and children and untreated historical patients with congenital toxoplasmosis. The Chicago Collaborative Treatment Trial. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;18:38-72.

McLeod R, Boyer K, Karrison T, et al. Outcome of treatment for congenital toxoplasmosis. 1981–2004: the national collaborative Chicago-based congenital toxoplasmosis study. Clin Infect Dis. 2006;42:1383-1394.

McLeod R, Kieffer F, Sautter M, et al. Why prevent, diagnose and treat congenital toxoplasmosis? Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 2009;104:320-344.

McLeod R, Boyer K, Roizen N, et al. The child with congenital toxoplasmosis. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 2000;20:189-208.

Mets MB, Holfels E, Boyer KM, et al. Eye manifestations of congenital toxoplasmosis. Am J Ophthalmol. 1997;123:1-16.

Montoya JG. Laboratory diagnosis of Toxoplasma gondii infection and toxoplasmosis. J Infect Dis. 2002;1855(Suppl):S73-S82.

Montoya JG, Liesenfeld O. Toxoplasmosis. Lancet. 2004;363:1965-1976.

Phan L, Kasza K, Jalbrzikowski J, et al. Longitudinal study of new eye lesions in children with toxoplasmosis who were not treated during the first year of life. Am J Ophthalmol. 2008;146:375-384.

Phan L, Kasza K, Jalbrzikowski J, et al. Longitudinal study of new eye lesions in treated congenital toxoplasmosis. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:553-559.

Remington JS, McLeod R, Thulliez P, et al. Toxoplasmosis. In Remington J, Klein J, Wilson C, Baker C, editors: Infectious diseases of the fetus and newborn infant, ed 7, Philadelphia: Saunders, 2010.

Remington JS, Thulliez P, Montoya JG. Recent developments for diagnosis of toxoplasmosis. J Clin Microbiol. 2004;42:941-945.

Roberts F, Mets MB, Ferguson DJP, et al. Histopathological feature of ocular toxoplasmosis in the fetus and infant. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1-58.

Roizen N, Kasza K, Karrison T, et al. Impact of visual impairment on measures of cognitive function for children with congenital toxoplasmosis: implications for compensatory intervention strategies. Pediatrics. 2006;118:e379-390.

Roizen N, Swisher C, Boyer K, et al. Developmental and neurologic outcome in congenital toxoplasmosis. Pediatrics. 1995;95:11-20.

Romand S, Wallon J, Franck J, et al. Prenatal diagnosis using polymerase chain reaction on amniotic fluid for congenital toxoplasmosis. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:296-300.

Stanford MR, Tan HK, Gilbert RE. Toxoplasmic retinochoroiditis presenting in childhood: clinical findings in a UK survey. Br J Ophthalmol. 2006;90:1464-1467.

The SYROCOT (Systematic Review on Congenital Toxoplasmosis) study group. Effectiveness of prenatal treatment for congenital toxoplasmosis: a meta-analysis of individual patient’s data. Lancet. 2007;369:115-122.

Vasconcelos-Santos DV, Machado Azevedo DO, Campos WR, et al. Congenital toxoplasmosis in southeastern Brazil: results of early ophthalmologic examination of a large cohort of neonates. Ophthalmology. 2009;116:2199-2205.

Wallon M, Franck J, Thulliez P, et al. Accuracy of real-time polymerase chain reaction for Toxoplasma gondii in amniotic fluid. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:727-733.

Wallon M, Kodjikian L, Binguiet C, et al. Long-term ocular prognosis in 327 children with congenital toxoplasmosis. Pediatrics. 2004;113:1567-1572.