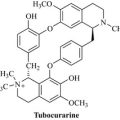

Chapter 10 Toxicity of herbal constituents

This chapter is not about toxic plants as such (see Nelson et al 2006), but about those plants used as herbal medicines and in therapy. Most common herbal remedies are fairly safe in clinical use; not because they are ‘natural’, but because the long history of use has uncovered some of the adverse effects.

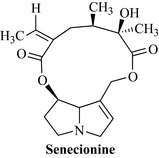

Pyrrolizidine alkaloids

These have only been reported in the plant families Boraginaceae, Asteraceae, Leguminosae, Apocynaceae, Ranunculaceae and Scrophulariaceae, and not in all species. Medicinal herbs that may be affected include comfrey (Symphytum spp.), butterbur (Petasites hybridus (L.) P. Gaertn., B. Mey. & Scherb.), alkanet (Alkanna tinctoria Tausch, Boraginaceae), coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara) and hemp agrimony (Eupatorium cannabinum L., Asteraceae). Not all pyrrolizidine alkaloids are toxic, only those that are unsaturated at the 1,2-position (e.g. senecionine; Fig. 10.1). These are liver toxins and can produce veno-occlusive disease of the hepatic vein as well as being hepatocarcinogenic, and their effects are cumulative. Several documented clinical examples can be found in the literature. Although highly toxic, they are chemically rather labile and may, therefore, not present the serious risk originally thought, at least in herbal medicines that have undergone a lengthy process involving heat. For example, when six commercial samples of comfrey leaf were tested, none of these alkaloids were detectable. However, in fresh plant material, and also root samples, they may be present in significant amounts. The total recommended maximum dose of these alkaloids is less than 1 μg daily for less than 6 weeks per year. If herbal products, which may contain these, are to be employed (and some are very useful, e.g. butterbur and coltsfoot; see Chapter 16), the content must be estimated and, if necessary, the alkaloids should be removed before use.

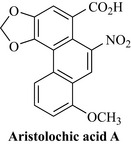

Aristolochic acid

Most species of birthwort (Aristolochia, known as snakeroot) and related genera including Asarum, all from the family Aristolochiaceae, contain aristolochic acid and aristolactams. Aristolochia has been found as an ingredient in a slimming formula along with dexfenfluramine and in Europe, since the mid 1990s, more than one hundred cases of nephropathy caused by the systemic and long term use of Chinese snakeroot (Aristolochia fangchi Y.C. Wu ex L.D. Chow & S.M. Hwang), mainly in these weight-loss preparations, has highlighted the risk of using preparations which contain aristolochic acids. Aristolochic acid A (Fig. 10.2) is nephrotoxic and has been responsible for several deaths from renal failure. Aristolochia and other species containing these compounds are banned from sale in Europe and the USA, but may still be present in imported Chinese medicines, and A. fangchi has been found substituted for Stephania tetrandra S. Moore. Herbs containing these substances must not be used. The disastrous consequences of using them have been a wake-up call for the regulatory authorities and the herbal industry. On the other hand, in many regions of the world species from the genus are widely used as local and traditional medicines especially in the treatment of gastrointestinal complaints like diarrhoea, of snake bites and poisoning, and of gynaecological conditions, including the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) such as syphilis and gonorrhoea (Heinrich et al 2009; Nortier et al 2000).

Aconitine and controversial claims about ‘detoxification’

Aconitum species (Ranunculaceae) are widely distributed throughout the northern hemisphere and have been used medicinally for centuries. They provide a fascinating example of a highly toxic botanical drug, which, according to claims made by some practitioners, can be detoxified by means of its method of preparation. The tubers and roots of Aconitum species such as Aconitum kusnezoffii Reichb. and Aconitum japonicum Thunb. are commonly used in Traditional Chinese Medicine in the treatment of conditions including syncope, rheumatic fever, painful joints, gastroenteritis, diarrhoea, oedema, bronchial asthma, various types of tumour and even some endocrinal disorders like irregular menstruation. However, the cardio- and neurotoxicity of this drug is potentially lethal, and the improper use of Aconitum in China, India, Japan and some other countries still results in a high risk of severe intoxication Singhuber et al 2009.

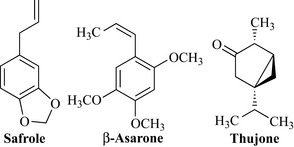

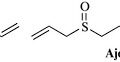

Monoterpenes and phenylpropanoids

Most mono- and sesquiterpenes found in essential oils are fairly safe, apart from causing irritation when used undiluted and allergic reactions in susceptible individuals. However, some have been shown to be carcinogenic, for example safrole (from Sassafras bark) and β-asarone (from Acorus calamus L.) (Fig. 10.3). They do not appear to give cause for concern when present in minute amounts in other oils. Methysticin, from nutmeg, is toxic in large doses, and has been postulated as being a metabolic precursor of the psychoactive drug methylene dioxymethamphetamine. Thujone (Fig. 10.3), which is present in wormwood (Artemisia absinthium L.) and in the liqueur absinthe, is also toxic and hallucinogenic in large doses.

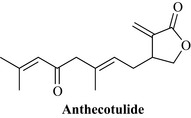

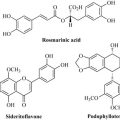

Sesquiterpene lactones

These compounds are present in many Asteraceae plants, and are often responsible for the biological activity of the herb. Some are cytotoxic and some are highly allergenic, which can cause problems if misidentification occurs of, for example, mayweed (Anthemis cotula) for one of the chamomiles (Anthemis nobilis L. or Matricaria recutita L.). Anthecotulide (Fig. 10.4) is one such allergen and is present in several species of the Asteraceae (the daisy family, Compositae).

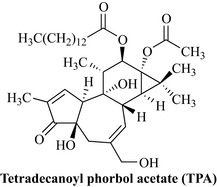

Diterpene esters

The phorbol, daphnane and ingenol esters are found in plants of the Euphorbiaceae and Thymeliaceae. Some are highly pro-inflammatory and are known to activate protein kinase C, as well as having tumour-promoting (co-carcinogenic) activity. The most important is tetradecanoyl phorbol acetate (formerly known as phorbol myristate acetate; Fig. 10.5), which is an important biochemical probe used in pharmacological research. Some of these plants were formerly used as drastic purgatives (e.g. croton oil, from Croton tiglium L., Euphorbiaceae) but should now be avoided in herbal products.

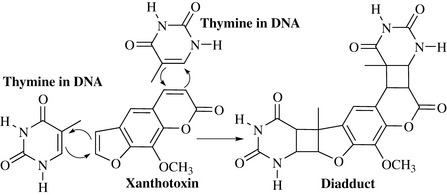

Furanocoumarins

Some furanocoumarins (e.g. psoralen, xanthotoxin and imperatorin), which are found in giant hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum Sommier & Levier) and other umbelliferous plants, as well as in some citrus peels, are phototoxic and produce photodermatitis and rashes on contact. They have a minor legitimate use in PUVA therapy (psoralen plus UV-A radiation) in the treatment of psoriasis, but this is an uncommon therapy used only in specialist hospital clinics. These compounds are known to form adducts with DNA, as shown in Fig. 10.6.

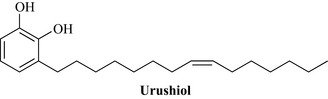

Urushiol derivatives

The urushiols (Fig. 10.7), anacardic acids and ginkgolic acids are phenolic compounds with a long side-chain. The uroshiols are found in poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans (L.) Kuntze) and poison oak [T. quercifolium (Michx.) Greene] and cause severe contact dermatitis. This is a major problem in the USA, but less so in Europe where the plants are not native. The anacardic acids, which are found in the liquor surrounding the cashew nut (Anacardium occidentale L.), are less toxic. The ginkgolic acids are reputed to cause allergic reactions; however, they are present in the Ginkgo biloba seed more than in the leaf, which is the medicinal part. Ginkgo rarely causes this sort of reaction so in practice it is not regarded as a health hazard.

Heinrich M., Chan J., Wanke S., Neinhuis Ch., Simmonds M.S.S. Local uses of Aristolochia species and content of aristolochic acid 1 and 2 – a global assessment based on bibliographic sources. J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2009;125:108-144.

Nelson L.S., Shih R.D., Balick M. Handbook of poisonous and injurious plants, second ed. The New York Botanical Garden: NY and Springer Heidelberg; 2006.

Nortier J.L., Martinez M.C., Schmeiser H.H., et al. Urothelial carcinoma associated with the use of a Chinese herb (Aristolochia fangchi). N. Engl. J. Med.. 2000;342:1686-1692.

Singhuber J., Zhu M., Prinz S., Kopp K. Aconitum in traditional Chinese medicine – a valuable drug or an unpredictable risk? J. Ethnopharmacol.. 2009;126:18-30.