CHAPTER 55 Total Elbow Arthroplasty for Juvenile Rheumatoid Arthritis

INTRODUCTION

Juvenile rheumatoid arthritis (JRA) is a disabling condition that affects nearly a quarter of a million children in the United States.3,45 It has been defined by the American Rheumatology Association3 as arthritis that has been present in at least one joint for 6 weeks to 3 months when the patient is younger than 16 years old. Patients with this affliction often present with stiff, painful elbows, and some may have disabling elbow ankylosis. This condition has implications regarding treatment. Just as the clinical manifestations of JRA may differ from those of adult rheumatoid arthritis in the hip, knee, and shoulder,26,28,45 the course of this disease process also differs in the elbow.20 Patients often have severe osseous atrophy, deformity, and soft tissue contractures about the elbow that require special consideration and may adversely affect treatment outcomes.8,9,11,14,15,20,21 We have also reconstructed extremely small joints and narrow intramedullary cavities.

Most patients with JRA who present with stiff, painful elbows have had prior treatment of other symptomatic joints and are functionally limited to only activities of daily living.6 The painful impairment of elbow function may have been overlooked by the patient or minimized by the physician because of the severity of other joint involvement as well as a general lack of awareness regarding treatment options and results. In one study, 15 of 19 patients with JRA had had an average of five (range, two to eight) previous arthroplasties or arthrodeses of other major joints (e.g., hip, knee, shoulder) before presentation for total elbow arthroplasty.6

EVALUATION

As with all inflammatory conditions, clinical assessment of patients with JRA must include a detailed evaluation of the ipsilateral shoulder, wrist, and hand. The assumption that shoulder motion compensates for loss of elbow flexion and extension is invalid (see Chapter 5). Thus, range of motion of the shoulder and elbow should be carefully and independently assessed. Although some controversy exists regarding the ideal order of surgical management in patients with multiple joint involvement, the most painful and functionally disabled joints should have priority.18 In the event that all joints are equally symptomatic, the next priority is usually given to the hand and wrist, because the function of the shoulder and elbow is to place a functional hand in space.

There are differences of opinion if the decision focuses on the priority of shoulder or elbow arthroplasty. Although one study suggests that elbow arthroplasty should have precedence over shoulder arthroplasty,16 others believe that shoulder arthroplasty should be performed first.38 Suggested reasons for proceeding with shoulder arthroplasty before elbow arthroplasty include the following38:

Our opinion has changed since we demonstrated in our surgical practice that greater functional benefit derives from the elbow replacement.18 This is shown by a markedly extended period before a patient requested to replace the shoulder after the elbow compared with requesting the elbow replacement after the shoulder is done first. Therefore, if the elbow had been replaced first, sufficient improvement often exists, so the shoulder operation can be delayed for a larger period than if the shoulder is replaced first.

The radiographs that are essential for evaluation of the JRA elbow are the anteroposterior and lateral views. The radiographic presentation of the JRA elbow has five distinct stages6,32: grade I indicates no radiographic changes with the exception of osteopenia associated with active synovitis; grade II, symmetric narrowing of the joint space with the architecture intact; grade III, alteration of the architecture of the joint that may be relatively mild (type A) or extensive (type B); grade IV, gross destruction of most or all of the articular architecture. A grade V, radiographic change was defined if a review of the JRA radiograph revealed an absence of an identifiable ulnohumeral joint on anteroposterior and lateral radiographs or by mature bony trabeculation crossing the ulnohumeral joint (Fig. 55-1). If severe bony atrophy is present, calibrated markers may be necessary for preoperative templating purposes.

TREATMENT ALTERNATIVES

Open communication between the rheumatologist, orthopedist, and physical therapist helps provide ideal care for these patients. The nonsurgical management of JRA differs little from that of adult rheumatoid arthritis. Improved results appear to be occurring from the use of disease-remitting agents (see Chapter 74). Efforts should be geared toward pain relief and especially maintenance of joint motion. Elbow splinting is unpredictable. Resting or night splints can be helpful. Judicious use of corticosteroid injections in the elbow joint may also be helpful for early symptoms. Gentle exercises should be performed regularly for the all important goal of maintaining mobility and muscle strength.

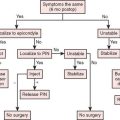

When nonoperative management fails to provide adequate relief of symptoms, surgical treatment alternatives include surgical or clinical synovectomy, interposition arthroplasty, and joint replacement. The relative roles of synovectomy and interposition arthroplasty of the rheumatoid elbow are discussed in Chapters 68 and 69 of this text. As previously emphasized, elbows with JRA have a propensity toward stiffness. Thus, if a synovectomy or interposition arthroplasty is proposed, concomitant anterior and posterior capsular releases may be necessary to re-establish functional range of motion. This was recently reaffirmed by a series of 24 synovectomies for JRA patients. The outcome was considered satisfactory in 72% at 5 years.30 Of importance was that motion did not improve in these patients. On the other hand, a more aggressive approach to débridement and removal of capsule and bony impingement might improve results, as was shown in the Mayo experience.7

TOTAL ELBOW ARTHROPLASTY: OPERATIVE TECHNIQUE

The technique of total elbow arthroplasty for the adult rheumatoid elbow is described in Chapter 54 of this text. In this patient in particular, to avoid potential complications, it is essential that the surgeon spend time planning preoperatively for the anatomic deformities and technical challenges that are especially common with elbows affected by JRA. Emphasis is placed on ensuring that the proper sized (small) implant is available to accommodate the small intramedullary canal, especially of the ulna. As mentioned earlier, this may require preoperative radiographs with calibrated templating markers. Be prepared to bend both humeral and ulnar component stems.

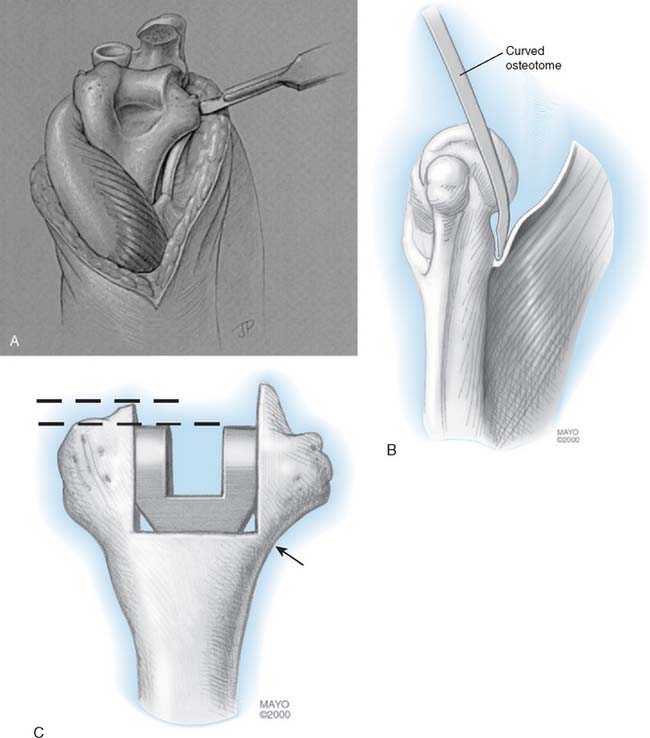

A posterior incision is used, and the ulnar nerve is routinely transferred anteriorly to a subcutaneous position. The triceps is then released in a subperiosteal manner from the olecranon, in continuity with the ulnar periosteum and the fascia of the forearm along with the anconeus.5 Again, elbows affected by JRA are characterized by stiffness and by very small, fragile bones; thus, care should be taken during the exposure to avoid excessive forces about the elbow, which could cause a fracture. If there is osseous ankylosis (grade V radiographic classification), a curved microsagittal saw or a small osteotome is used to re-establish the joint line after osseous landmarks are identified. Care is taken to restore the proper center of rotation of the ulnohumeral joint to maximize the biomechanical function of the prosthetic elbow.14,25

With severe soft tissue contracture or osseous ankylosis, or both, circumferential capsular and collateral ligament releases are necessary to maximize postoperative motion and function. For this reason, unlinked prostheses depend on functional collateral ligaments and proper soft tissue balancing; therefore, these prostheses are not typically indicated in this clinical situation. Rather, a linked semiconstrained prosthesis is employed, the collateral ligaments are released, and the anterior capsule is completely excised (Fig. 55-2) and further reflected from the distal aspect of the humerus with an osteotome or blunt periosteal elevator. These maneuvers and this prosthesis allow the greatest possible motion and stability for patients who have severe preoperative stiffness.

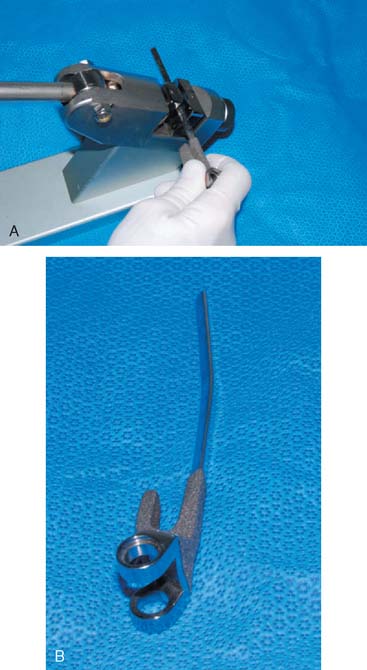

The intramedullary canals of the humerus and the ulna characteristically are very narrow or are completely obliterated in some patients with JRA. Thus, care must be taken in the identification and preparation of these canals. During preparation, it is important to stay centered and to remain within the confines of the cortical bone. We thus employ a small (4-mm) cannulated flexible reamer and intramedullary guide for this purpose (Fig. 55-3). The Coonrad-Morrey implant system now includes an extra small humeral and ulnar component. In the ulnar component, the intramedullary cross-section diameter is only 3 mm (Fig. 55-4). Although the use of individualized custom prostheses has not been necessary in our experience, it is important to have an appropriate inventory of prosthetic sizes available to address the small intramedullary canal. In elbows in which an angular change is needed in the ulnar or humeral component, the Coonrad-Morrey prosthetic ulnar stem may be slightly modified with a cam-lever bending device (Fig. 55-5).

FIGURE 55-3 A series of cannulated reamers ranging from 5 to 7.5 mm are helpful to prepare the small ulnar canal.

The cementing technique used in patients who have JRA differs little from standard techniques. Tobramycin-impregnated cement (1 g/40 g cement) is routinely used in an effort to lessen the likelihood of infection, and cement for both the humeral and ulnar component is inserted with an intramedullary injection system. Because many patients who have JRA have involvement of the ipsilateral shoulder, which has either had or may eventually require prosthetic replacement (Fig. 55-6), a cement restrictor is deployed to limit the level of cement injected in the humerus. The short, 10-cm extra small diameter humeral component is used.

AFTERCARE

After repair of the extensor mechanism5 and routine closure, the elbow is placed in a compressive dressing and elevated in a vertical elbow sling for 24 hours. The patient is then allowed to use the extremity as tolerated for activities of daily living. Patients who have JRA are encouraged to use the elbow to enhance postoperative motion and a Mayo Elbow Brace is typically used. (See Chapter 11.)

OUTCOME

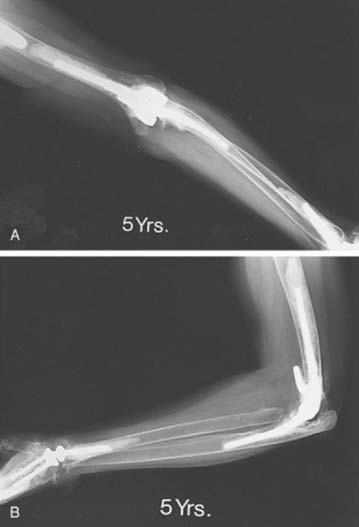

Even today, a Medline search reveals only one study that has been published regarding total elbow arthroplasty in patients who have JRA. The long-term results in 19 patients (in 24 elbows) with JRA who had been managed with total elbow arthroplasty at the Mayo Clinic were evaluated. At an average of 7.4 years (range 2 to 14) after the operation, there was an improvement in the average Mayo Elbow Performance Score (MEPS) from 31 points (range, 5 to 55) preoperatively to 90 points (range, 55 to 100) postoperatively.6 In 22 (96%) of the 23 elbows available at the most recent follow-up evaluation, there was little or no pain, but the improvement in the range of motion was not as reliable. The average arc of flexion improved 27 degrees from only 63 degrees preoperatively to 90 degrees postoperatively. The mean postoperative arc of flexion was between 35 to 125 degrees. Examination of the four elbows that had been completely ankylosed before the procedure revealed an average arc of 73 degrees after the operation, and evaluation of the 20 ipsilateral wrists that were not limited by disease revealed that pronation and supination had been maintained. The average functional MEPS improved from 9 points (range, 0 to 25) preoperatively to 23 points (range, 15 to 25) postoperatively (P < .001). Eighteen elbows (78%) were noted by patients to cause no difficulties with standard daily activities.

These results with regard to pain relief (6%) compare favorably with or are better than those reported in published series of elbow arthroplasty for adults who had rheumatoid arthritis* and other diagnoses.19,34,35,36 This fact is important when considering other options (see Fig. 55-6).12,22,29,44

Improvements in the range of motion after elbow arthroplasty in these patients are not as reliable as with most other diagnostic categories including the expected improvement in motion following from arthroplasty in the adult with rheumatoid arthritis.11,33

COMPLICATIONS

There were 13 complications that affected 12 of the 24 elbows. Early complications (including a fracture of the olecranon, subluxation of a resurfacing prosthesis, elbow stiffness, and problems with wound healing) that were appropriately diagnosed and treated did not adversely affect the long-term outcome. Late complications include aseptic loosening of a press-fit unlinked prosthesis, instability of an unlinked prosthesis, and a worn bushing of the linked implant led to three poor results. Importantly, none of the 18 semiconstrained prostheses had radiographic evidence of loosening at the most recent follow-up evaluation. The implications of this observation are particularly relevant for patients with JRA who undergo an elbow arthroplasty at a relatively young age. This position is supported by the demonstration that the functional laxity of the Coonrad-Morrey prosthesis is consistently less than its inherent structural laxity.40 This explains the low rate of aseptic loosening of this implant design.

SUMMARY AND CONCLUSION

Total elbow arthroplasty for JRA provides rewarding pain relief and improvements in function. However, the favorable restoration of range of motion that is seen after elbow arthroplasty in patients who have adult rheumatoid arthritis cannot be expected in this patient group. Because many elbows affected by JRA have pre-existing anatomic deformities, there are complex and challenging technical considerations, and thorough preoperative planning must be emphasized. This is particularly relevant with regard to determining the size and type of prosthetic implant. Finally, experience with operations on the elbow, and with prosthetic replacement in particular, will increase the likelihood of a satisfactory outcome (Fig. 55-7).

1 Barrett W.P., Thornhill T.S., Thomas W.H. Nonconstrained total shoulder arthroplasty in patients with polyarticular rheumatoid arthritis. J. Arthroplasty. 1989;4:91.

2 Boyd A.D.Jr., Thomas W.H., Scott R.D., Sledge C.B., Thornhill T.S. Total shoulder arthroplasty versus hemiarthroplasty: Indications for glenoid resurfacing. J. Arthroplasty. 1990;5:329.

3 Brewer E.J. Criteria for the classification of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Bull. Rheum. Dis. 1972;23:712.

4 Brumfield R.H., Kuschner S.H., Gellman H., Redix L., Stevenson D.V. Total elbow arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 1990;5:359.

5 Bryan R.S., Morrey B.F. Extensive posterior exposure of the elbow: A triceps-sparing approach. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;166:188.

6 Connor P.M., Morrey B.F. Total elbow arthroplasty in patients who have juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1998;80A:678.

7 Cill, A., Veillette, C. J. H., O’Driscoll, S. W., and Morrey, B. F.: Arthroscopic synovectomy of the elbow in inflammatory arthritis. (Paper submitted for review 2008)

8 Dee R. Total replacement of the elbow joint. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1973;4:415.

9 Dennis D.A., Clayton M.L., Ferlic D.C., Stringer E.A., Bramlett K.W. Capitellocondylar total elbow arthroplasty for rheumatoid arthritis. J. Arthroplasty. 1990;5(suppl):S83.

10 Ewald F.C., Scheinberg R.D., Poss R., Thomas W.H., Scott R.D., Sledge C.B. Capitellocondylar total elbow arthroplasty: Two- to five-year follow-up in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:1259.

11 Ewald F.C., Simmons E.D., Sullivan J.A., Thomas W.H., Scott R.D., Poss R., Thornhill T.S., Sledge C.B. Capitellocondylar total elbow replacement in rheumatoid arthritis: Long-term results. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1993;75A:498.

12 Ferlic D.C., Patchett C.E., Clayton M.L., Freeman A.C. Elbow synovectomy in rheumatoid arthritis: Long-term results. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1987;220:119.

13 Figgie H.E.III, Inglis A.E., Goldberg V.M., Ranawat C.S., Figgie N.P., Wile J.M. An analysis of factors affecting the long-term results of total shoulder arthroplasty in inflammatory arthritis. J. Arthroplasty. 1988;3:123.

14 Figgie H.E., Inglis A.E., Mow C. A critical analysis of biomechanical factors affecting functional outcome in total elbow arthroplasty. J. Arthroplasty. 1986;1:169.

15 Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Mow C.S., Figgie H.E. Total elbow arthroplasty for complete ankylosis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1989;71A:513.

16 Friedman R.J., Ewald F.C. Arthroplasty of the ipsilateral shoulder and elbow in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69A:661.

17 Garrett J.C., Ewald F.C., Thomas W.H., Sledge C.B. Loosening associated with G.S.B. hinge total elbow replacement in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res.. 1977;127:170.

18 Gill D.R.J., Morrey D.F. The Coonrad-Morrey total elbow arthroplasty in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: 10-15 year follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1998;80A:1327.

19 Inglis A.E. Revision surgery following a failed total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1982;170:213.

20 Inglis A.E., Figgie M.P. Septic and nontraumatic conditions of the elbow: Rheumatoid arthritis. In: Morrey B.F., editor. The Elbow and Its Disorders. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1993:753.

21 Inglis A.E., Pellicci P.M. Total elbow replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1980;62A:1252.

22 Jonsson B., Larsson S.E. Elbow arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis: Function after 1-2 years in 20 cases. Acta Orthop. Scand. 1990;61:344.

23 Kasten M.D., Skinner H.B. Total elbow arthroplasty: An 18-year experience. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1993;290:177.

24 Kelly I.G., Foster R.S., Fisher W.D. Neer total shoulder replacement in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69B:723.

25 King G.J.W., Glauser S.J., Westreich A., Morrey B.F., An K.N. In vitro stability of an unconstrained total elbow prosthesis: Influence of axial loading and joint flexion angle. J. Arthroplasty. 1993;8:291.

26 Kraay M.J., Figgie M.P., Inglis A.E., Wolfe S.W., Ranawat C.S. Primary semiconstrained total elbow arthroplasty: Survival analysis of 113 consecutive cases. J. Bone Joint Surg.. 1994;76B:636.

27 Kudo H., Iwano K., Prefecture K. Total elbow arthroplasty with a non-constrained surface-replacement prosthesis in patients who have rheumatoid arthritis: A long-term follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1990;72A:355.

28 Levine W.N., Scott R.D., Sledge C.B., Thomas W., Thornhill T.S. Shoulder arthroplasty in juvenile rheumatoid arthritis: Mean 12-year follow-up. Orthop. Trans. 1995;19:365.

29 Ljung P., Jonsson K., Larsson K., Rydholm U. Interposition arthroplasty of the elbow with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1996;5:81.

30 Maenpaa H., Kuusela P., Lehtinen J., Savolainen A., Kautiainen H., Belt E. Elbow synovectomy on patients with juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 2003;412:65.

31 McCoy S.R., Warren R.F., Bade H.A.III, Ranawat C.S., Inglis A.E. Total shoulder arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Arthroplasty. 1989;4:105.

32 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semiconstrained devices. In: Morrey B.F., editor. Reconstructive Surgery of the Joints. 2nd ed. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 1996:515.

33 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semiconstrained arthroplasty for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:479.

34 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A. Semiconstrained elbow replacement for distal humeral nonunion. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1995;77B:67.

35 Morrey B.F., Adams R.A., Bryan R.S. Total replacement for post-traumatic arthritis of the elbow. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1991;73B:607.

36 Morrey B.F., Bryan R.S. Revision total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1987;69A:523.

37 Morrey B.F., Bryan R.S., Dobyns J.H., Linscheid R.C. Total elbow arthroplasty: A five-year experience at the Mayo Clinic. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1981;63A:1050.

38 Neer C.S.II. Glenohumeral arthroplasty. In: Neer C.S.II, editor. Shoulder Reconstruction. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1990:167.

39 Neer C.S.II, Watson K.C., Stanton F.J. Recent experience in total shoulder replacement. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1982;64A:319.

40 O’Driscoll S.W., An K.N., Korinek S., Morrey B.F. Kinematics of semi-constrained total elbow arthroplasty. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74B:297.

41 Rosenberg G.M., Turner R.H. Nonconstrained total elbow arthroplasty. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1984;187:154.

42 Ruth J.T., Wilde A.H. Capitellocondylar total elbow replacement: A long-term follow-up study. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1992;74A:95.

43 Rydholm U., Tjornstrand B., Pettersson H., Lidgren L. Surface replacement of the elbow in rheumatoid arthritis: Early results with the Wadsworth prosthesis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66B:737.

44 Rymaszewski L.A., MacKay I., Ames A.A., Miller J.H. Long-term effects of excision of the radial head in rheumatoid arthritis. J. Bone Joint Surg. 1984;66B:109.

45 Scott R.D., Sledge C.B. The surgery of juvenile rheumatoid arthritis. In: Kelly W.N., Harris E.D., Ruddy S., Sledge C.B., editors. Textbook of Rheumatology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: W. B. Saunders; 1985:1910.

46 Souter W.A. Arthroplasty of the elbow: With particular reference to metallic hinge arthroplasty in rheumatoid arthritis. Orthop. Clin. North Am. 1973;4:395.