19 Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection

I. CASE

A. Fetal echocardiography findings

1. Fetal echocardiography reveals situs solitus of the atria, levocardia, left aortic arch, and a normal heart rate of 140 bpm.

2. The four-chamber view is abnormal, with mildly enlarged right heart and a normal cardiac axis and position.

3. Cardiac size is normal (cardiothoracic ratio = 0.24).

4. The proximal pulmonary venous flow pattern is abnormal by Doppler sampling in the lung near the hilum.

5. The pulmonary artery is normal.

6. There is a small aneurysm of the fossa ovalis, and the entry of the pulmonary veins into the LA could not be visualized by two-dimensional Doppler; however, there was a gap between the descending aorta and the posterior wall of the left atrium (LA).

7. The umbilical artery Doppler is normal.

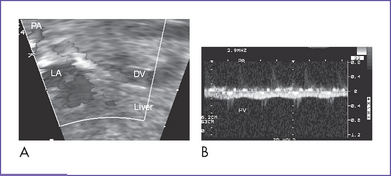

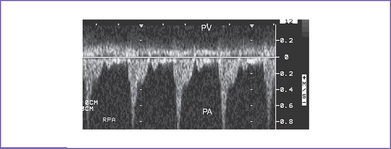

8. A descending vein near the aorta was seen with flow toward the liver (Fig. 19-1A).

9. Diagnosis of total anomalous pulmonary venous return with obstruction was also suspected due to the intracardiac disproportion and the abnormal (flat) pulmonary venous Doppler (Fig. 19-1B), and failure to identify the pulmonary veins.

D. Fetal management and counseling

1. Amniocentesis was offered but declined.

2. Follow-up included serial antenatal studies at 4- to 6-week intervals.

a. There is evidence of abnormal pulmonary Doppler (increased pulsatility index), which could suggest high pulmonary vascular resistance due to pulmonary venous obstruction.

b. Attempts at further defining the anatomy of the pulmonary venous connection are important, and in the case of the present patient, a descending vein pathway below the diaphragm was identified at follow-up studies consistent with a subdiaphragmatic connection. It is important as well that the pulmonary veins and confluence are reassessed for evidence of progressive obstruction or reduced growth. The branch pulmonary artery diameters also might not grow normally if there is high downstream resistance to flow due to pulmonary venous obstruction.

c. RV size (shortening), function, and Tei index (myocardial performance index) are monitored serially. Left ventricle (LV) growth is followed.

d. Adequacy of the foramen ovale is imaged to exclude obstruction at that level due to the increased flow.

e. The ductus venosus velocity is monitored for signs of portal hypertension.

F. Neonatal management

a. After birth, the baby will be assessed by the cardiac team. A low level of oxygenation (pulse oximeter <50% with low pressure and high oxygen ventilation) and progressive pulmonary hypertension and edema are the primary indications for intervention.

b. Management of the pulmonary hypertension includes assisted ventilation, although hyperventilation can also worsen the pulmonary edema and thus make oxygenation more difficult. For the most severe cases, an exit type of procedure with extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) available for resuscitation may be necessary.

c. For total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (TAPVC) to the ductus venosus with obstruction, some have advocated the use of prostaglandin E1 (PGE1) infusion, but this is controversial.

d. Severely obstructed TAPVC requires emergency surgery because it cannot be medically managed.

a. Corrective repair consists of:

b. Nitric oxide might be helpful to treat associated persistent pulmonary hypertension, especially after surgery.

G. Follow-up

1. The long-term outcome after surgical repair of TAPVC is excellent. Because the surgical repair results in a normal circulation, these children are typically expected to grow and develop normally.

2. Long-term survival depends in part on the development of pulmonary vein stenosis, which is a rare but lethal complication.

a. Stenosis can occur within weeks or months after the repair.

b. Obstruction can occur at the site of surgical repair or can result from abnormalities of the pulmonary veins themselves. Such pulmonary vein obstruction can lead to a shortness of breath or wheezing, particularly on exertion.

c. The diagnosis can be somewhat difficult but can be made at echocardiography and confirmed at cardiac catheterization.

d. In the first year after a neonatal repair, the infant should be seen at more frequent intervals to exclude progressive pulmonary venous obstruction. Thereafter, yearly cardiology assessments that include echocardiography should be provided.

3. Abnormal cardiac rhythm is another late complication of TAPVC.

a. Because of the extensive atrial surgery involved in the repair, some patients experience abnormal electrical impulses arising in the atrium.

b. If such impulses occur in isolation, they are typically benign.

c. On rare occasions, sustained episodes of tachycardia or bradycardia could require treatment.

H. Risk of recurrence

1. Some reports have shown that TAPVC can run in families.

2. Bleyl and colleagues (1993) reported on a large Utah–Idaho family in which nonsyndromic TAPVC appeared to be inherited as an autosomal dominant trait with incomplete penetrance and variable expression. The family contained 14 affected members.

3. Solymar and colleagues (1987) reported three pairs of siblings with TAPVC. The types of the anomalous venous return (supra- or infracardial connections) varied within the families, indicating that genetic regulation deals with the LA connection to the intrapulmonary veins.

I. Outcome of this case

1. The baby was born weighing 3.5 kg and had Apgar scores of 8 at 1 minute and 8 at 5 minutes.

2. Venous and arterial lines were placed, and the baby was taken immediately to the neonatal intensive care unit.

3. Pulse oximeter reading was 75% to 80%.

5. Postnatal transthoracic echocardiogram confirmed the diagnosis of obstructed TAPVC (infradiaphragmatic).

6. The baby had no dysmorphic features.

7. The baby was stabilized and taken to cardiac surgery, where he had successful repair.

8. His postoperative course was marked by persistent transient pulmonary hypertension.

9. He was discharged home 10 days postoperatively with a normal feeding pattern.

II. YOUR HANDY REFERENCE

A. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection

a. TAPVC affects about 1 in 17,000 live births.

b. It is not a common antenatal diagnosis. In the fetal series of Allan and Sharland (1994), only three isolated cases of TAPVC were reported.

c. Given the subtle abnormalities in TAPVC, the diagnosis could be missed even during a targeted fetal exam.

d. TAPVC is often identified prenatally when it occurs in combination with significant cardiac defects such as coarctation, hypoplastic left heart syndrome, or heterotaxy syndrome.

e. The Baltimore–Washington Infant Study (BWIS), a population-based exploratory case-control study of cardiovascular malformations, identified 41 cases of TAPVC during the period 1981 to 1987. These constituted 1.5% of all cardiovascular malformations (N = 2659), with a regional prevalence of 6.8 per 100,000 live births.

a. The hospital mortality for the surgical repair of isolated TAPVC ranges from 2% to 20% in the presence of obstruction of the vein(s).

b. In the presence of significant intracardiac anomaly, the outcome of totally or partly anomalous venous connection is poor, particularly in right atrial (RA) isomerism, asplenia syndrome, or other forms of single-ventricle physiology.

c. Operative repair of anomalous pulmonary venous connections complicates the surgical treatment for single ventricle anatomy and physiology.

d. Long-term survival depends in part on the development of pulmonary vein stenosis. This is a lethal complication that occurs in a minority of patients.

3. Associated syndromes and extracardiac anomalies.

a. As an isolated cardiac abnormality, TAPVC is rarely associated with extracardiac malformations.

b. It could be found in the setting of a heterotaxy syndrome (more in RA isomerism than in LA isomerism).

c. Chromosomal abnormalities are rarely associated with isolated TAPVC, although one potentially diagnosable condition is cat eye syndrome, in which there is duplication of chromosome 22q11 in the critical cat eye region.

a. Ventricular disproportion with a larger right than left ventricle might suggest coarctation of the aorta or other form of left heart obstruction or foramen ovale obstruction. It can also occur in third-trimester intrauterine growth restriction.

b. One also must be cautious with largely RV dilation with a normal-sized LV. This can result from increased blood flow to the RV and relatively normal flow to the LV, such as in vein of Galen aneurysm.

5. Clues to fetal sonographic diagnosis.

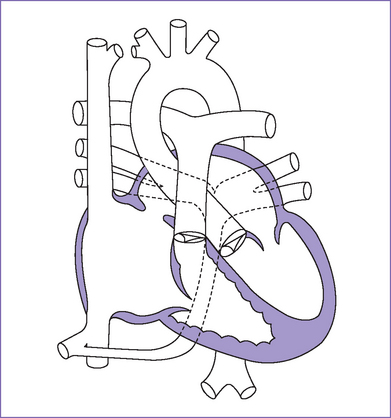

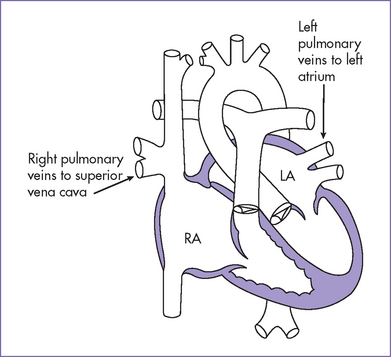

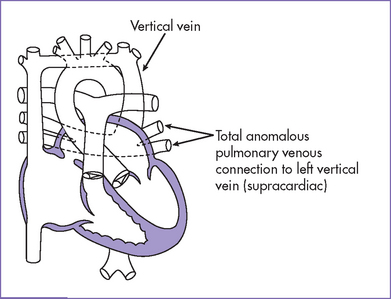

a. Excluding the diagnosis is achieved by identifying at least one right-sided and one left-sided pulmonary vein connecting to the posterior wall of the LA on either side of the descending aorta (Figs. 19-2 to 19-6).

b. Clues to nonobstructed TAPVC.

6. Cardiovascular profile score.

a. An abnormal score is not expected, but it should be monitored every month prenatally.

b. Because the RV has volume overload, its function should be followed by serial fetal echocardiography.

7. Immediate postnatal management for patients without prenatal diagnosis of TAPVC.

a. Check the pulse oximeter reading, which is acceptable above 95%. If it is lower, do the hyperoxia test.

b. The baby might present with severe cyanosis, poor systemic output, pulmonary hypertension, and pulmonary edema with normal or small cardiac size on chest x-ray.

c. In this scenario, the newborn should be transferred to the neonatal or pediatric (cardiac if available) intensive care unit (ICU) for further assessment and management or directly to the operating room if the surgical team is ready to place the infant on bypass. If obstructed TAPVC is strongly suspected before birth, one might even have the ECMO circuit available to transfer the baby in a more stable situation to the operating room.

d. Affected infants with less obstruction initially can later develop progressive obstruction to pulmonary venous flow or right-to-left atrial shunt through a restrictive ASD and can present in infancy with cyanosis and severely dilated RV. Pulmonary hypertension usually develops in this situation.

e. Occasionally, TAPVC is not associated with obstruction. Such patients can present with cyanosis, clinical signs of left-to-right shunt with congestive heart failure, and RA and RV volume overload. The TAPVC is usually repaired more electively in this situation.

c. TAPVC with connection above the diaphragm is associated with an increase in right heart flow, resulting in discrepancy in arterial, ventricular, and great artery size, with a smaller left heart and relatively dilated right heart structures.

d. A TAPVC below the diaphragm might not increase the right heart size because a significant portion of the venous return from the IVC can drain in utero across the foramen ovale to the LA.

a. Long-term outlook depends on the success of the surgical repair and whether or not the pulmonary veins themselves are normal.

b. In some situations, particularly TAPVC in RA isomerism, there may be more diffuse pulmonary venous hypoplasia and obstruction, which is fatal.

10. Risk of recurrence: The suggested recurrence risk is 2% to 3% in the absence of chromosomal abnormalities or positive family history.

Fig. 19-2 Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection (supracardiac).

Modified from Mullins CE, Mayer DC: Congenital Heart Disease: A Diagrammatic Atlas. New York, Liss, 1988.

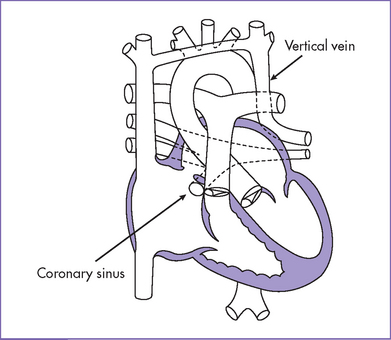

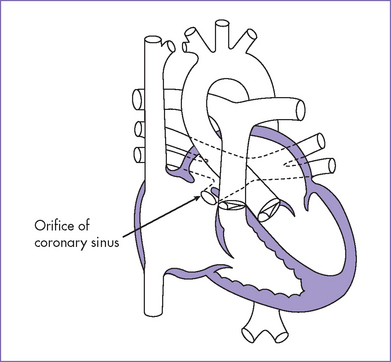

Fig. 19-4 Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection to coronary sinus.

Modified from Mullins CE, Mayer DC: Congenital Heart Disease: A Diagrammatic Atlas. New York, Liss, 1988.

B. Partial anomalous pulmonary venous return

1. Abnormalities of the pulmonary venous connections can involve one or more of the pulmonary veins. They include:

a. Isolated single anomalous vein.

b. Anomalous right upper pulmonary vein (most often seen in sinus venosus type of ASD).

c. Anomalous pulmonary vein or veins with secundum ASD (rare).

d. Anomalous right lower pulmonary vein with right lung hypoplasia or scimitar syndrome (rare).

2. In partially anomalous pulmonary venous return (PAPVC), one or two or even three pulmonary veins drain into the RA or connect abnormally with a systemic vein (usually SVC).

3. PAPVC can be associated with a secundum ASD.

4. A patient with PAPVC is usually asymptomatic and might present later in childhood with clinical features of left-to-right shunt with dilated RA and RV (volume overload).

5. Partial APVC can occur in association with many other different intracardiac defects. In single-ventricle lesions, this can represent a serious problem, particularly if it is not correctable, given the need for unobstructed pulmonary venous blood flow in Fontan physiology.

6. Infants can present in the neonatal period with respiratory distress related to right lung hypoplasia or pulmonary hypertension due to obstruction of the right pulmonary veins.

III. TAKE-HOME MESSAGE

A. Diagnosis

1. Fetal diagnosis of TAPVC and PAPVC is difficult.

a. Consistent assessment of color and pulsed Doppler sampling of at least a right and a left pulmonary vein on every fetal echo examination can detect this disease (continuous turbulent flow in the vertical vein and monophasic continuous flow in the pulmonary veins) and even exclude the more significant forms of partial APVR.

b. Recognition of a gap between the posterior wall of the LA and descending aorta, which normally are juxtaposed, facilitates identification of the pulmonary venous confluence and confirmation of this diagnosis.

2. Detection postnatally requires a high index of suspicion in a neonate with respiratory distress syndrome.

3. One type of partial anomalous venous connection is scimitar syndrome. In this syndrome, one or more of the right pulmonary veins drain anomalously into the IVC. In fetal life there is dextroposition (as the heart is shifted toward the right chest), a small right pulmonary artery, and often an aortopulmonary collateral.

B. Treatment

1. Prevention of late pulmonary venous obstruction continues to be a cornerstone of successful repair of TAPVC.

2. Improvements in surgical technique as well as preoperative and postoperative management account for the reduction in mortality and reoperation for most types of TAPVC, particularly in isolation.

3. The presence of a small venous confluence and diffuse pulmonary vein stenosis remains a risk factor for adverse outcome.

C. Prognosis

1. TAPVC with obstruction and particularly when in isolation is a lethal condition with potential for improved survival with a prenatal diagnosis and appropriate planning of perinatal and neonatal medical and surgical management.

2. Operative mortality for TAPVC with isomerism with single ventricle physiology approaches 100%.

Allan LD, Sharland GK, Milburn A, et al. Prospective diagnosis of 1,006 consecutive cases of congenital heart disease in the fetus. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1994;23(6):1452-1458.

Bando K, Turrentine MW, Ensing GJ, et al. Surgical management of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. Thirty-year trends. Circulation. 1996;94(9 Suppl):II12-II16.

Bleyl S, Ruttenberg HD, Carey JC, Ward K. Familial total anomalous pulmonary venous return: A large Utah–Idaho family. Am J Med Genet. 1994;52(4):462-466.

Bove EL, de Leval MR, Taylor JF, et al. Infradiaphragmatic total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage: Surgical treatment and long-term results. Ann Thorac Surg. 1981;31(6):544-550.

Correa-Villasenor A, Ferencz C, Boughman JA, Neill CA. Total anomalous pulmonary venous return: Familial and environmental factors. The Baltimore–Washington Infant Study Group. Teratology. 1991;44(4):415-428.

Freedom RM, Hashmi A. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connections and consideration of the Fontan or one-ventricle repair. Ann Thorac Surg. 1998;66(2):681-682.

Heinemann MK, Hanley FL, Van Praagh S, et al. Total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage in newborns with visceral heterotaxy. Ann Thorac Surg. 1994;57(1):88-91.

Jonas RA, Smolinsky A, Mayer JE, Castaneda AR. Obstructed pulmonary venous drainage with total anomalous pulmonary venous connection to the coronary sinus. Am J Cardiol. 1987;59(5):431-435.

Lamb RK, Qureshi SA, Wilkinson JL, et al. Total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage. Seventeen-year surgical experience. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1988;96(3):368-375.

Ricci M, Elliott M, Cohen GA, et al. Management of pulmonary venous obstruction after correction of TAPVC: Risk factors for adverse outcome. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2003;24(1):28-36.

Sahn DJ, Allen HD, Lange LW, Goldberg SJ. Cross-sectional echocardiographic diagnosis of the sites of total anomalous pulmonary venous drainage. Circulation. 1979;60(6):1317-1325.

Solymar L, Sabel KG, Zetterqvist P. Total anomalous pulmonary venous connection in siblings. Report on three families. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1987;76(1):124-127.

Valsangiacomo ER, Hornberger LK, Barrea C, et al. Partial and total anomalous pulmonary venous connection in the fetus: Two-dimensional and Doppler echocardiographic findings. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2003;22(3):257-263.

Van Hare GF, Schmidt KG, Cassidy SC, et al. Color Doppler flow mapping in the ultrasound diagnosis of total anomalous pulmonary venous connection. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 1988;1(5):341-347.

Wong ML, McCrindle BW, Mota C, Smallhorn JF. Echocardiographic evaluation of partial anomalous pulmonary venous drainage. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995;26(2):503-507.

Yeager S, Sander SP, Spevak PJ, et al. Prenatal echocardiographic diagnosis of pulmonary and systemic venous anomalies. Am Heart J. 1994;128:397-405.