How to Change General Surgery Residency Training

The training of general surgeons in the United States can trace its roots back to the system introduced by William Stewart Halsted at the Johns Hopkins Hospital, and many of the unique components persist today [1]. The training was hospital based, university sponsored, with the expectation that residents would gain knowledge and understanding of the scientific basis of surgical principles, ultimately resulting in increased responsibility over several years of training [2]. This training culminated in a final period of near-total independence and autonomy. The results of this training under Halsted were quite remarkable, and those who completed the Halsted training went on to direct departments of surgery at the leading institutions of the day [3].

General surgery residency training has been largely unchanged for the last 100 years. The most substantive change to the structure of training was the abandonment of the pyramidal system (where many medical school graduates entered surgical residency, but only one ascended to be the chief resident) and the adoption of the rectangular surgical residency program. This program was introduced in 1939 by Edward D. Churchill at the Massachusetts General Hospital [4]. Churchill initiated the current system we have where all entering trainees are expected to finish training at the hospital they began.

In the 1990s, general surgery became more separated into its own component subspecialties, as both training and practice became more focused. Surgeons (especially in academic centers) desired a more limited practice, and patients sought care by physicians with special expertise and training. Although many trainees went on to practice general surgery, an increasing number of residency graduates opted for fellowship training after completion of general surgery residency. A few of fellowships were distinct from general surgery (plastic surgery, cardiothoracic surgery, pediatric surgery) and for the most part, these surgeons no longer practice general surgery. Several subspecialties remain closely linked to the practice of general surgery. Most have training programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME); but non–ACGME-approved fellowships (transplant, surgical oncology, minimally invasive surgery, bariatric surgery, endocrine surgery, breast surgery, hepatopancreatobiliary surgery, trauma, acute care surgery) have developed for a multitude of reasons, including the lack of graduate medical education funding, the ability to bill for the services of non-ACGME fellows, and not wanting ACGME oversight for work hours. Most importantly, however, may be the realization that additional training and focused practice results in better patient outcomes [5–7]. For those interested in an academic career, narrowing of one’s practice allows special expertise that may enhance academic productivity and increase patient referrals to tertiary centers.

Two technical advancements of the 1990s fundamentally changed general surgery: the introduction of laparoscopic cholecystectomy and the advent of endovascular techniques. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy was first performed by Philippe Mouret and Francois Dubois in France. When a video was presented at the 1987 Society of American Gastrointestinal Endoscopic Surgeons video session by Jacques Perissat, it revolutionized general surgery [8]. Other procedures followed and laparoscopic adrenalectomy, appendectomy, and colectomy have become the preferred technique for many patients. The inadequacy of minimally invasive surgical training in general surgery residency led to an explosion (more than 100) non–ACGME-approved minimally invasive and bariatric surgery fellowships. Some think that laparoscopic training is a fad and will eventually be encompassed into general surgery residency training. Until this happens, minimally invasive surgery fellowships, which have become one of the most popular choices of general surgery residency graduates, has the potential to remain a separate discipline from general surgery. Up until the mid-1990s, many general surgeons were able to perform both general and vascular surgery in their practice. The advent of endovascular treatment of abdominal aortic aneurysmal disease and subsequent extension of infrainguinal occlusive disease has separated the field of vascular surgery from general surgery. To practice modern vascular surgery, a surgeon must have endovascular skills, and the American Board of Surgery (ABS) now recognizes that although general surgeons do need to have some familiarity with vascular surgery, vascular surgery is now a unique discipline, and promotes that the path to proficiency in vascular surgery requires completion of a vascular surgery residency.

In the last two decades, there have been significant changes to graduate medical education that have influenced the ability of residency graduates to feel confident about independent practice. The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (the primary funder of graduate medical education) implemented more stringent rules surrounding the supervision of residents performing operations in 1996 [9,10]. The teaching physician was required to be present for the key portion of any operation and any clinic or hospital visit they are going to bill for. Although these changes should be commended for ensuring adequate supervision, they may have had the unintended consequence of residents going into practice feeling less than secure in their abilities to make independent operative decisions. In 2003, the ACGME instituted duty hour restrictions that limited a resident to an 80-hour workweek [11]. Most recently, the ACGME amended their standards to limit the interns (PGY-1) to 16 hours per day [12]. The new regulations recommend that interns should have 10 hours (and must have at least 8 hours) free of duty between scheduled duty periods. For these reasons, and several others, more than 80% of general surgery residency graduates enter fellowships. Because many of those who complete fellowships narrow their practices, there remains a shortage of general surgeons capable and interested in practicing broad-based general surgery [13–15]. There is an acknowledged need to provide general surgeons for rural communities, but there is an equivalent obligation to provide qualified general surgeons to care for patients in community hospitals (where most patients are cared for), including managing common conditions, taking emergency room calls, and performing emergency operations.

The challenge of redesigning general surgery residency training is to simultaneously meet these two seemingly competing objectives: to provide general surgeons competent to be independent practitioners and (for most residents) to optimally prepare them for fellowship training. The most common procedures done by general surgeons in practice are listed in Table 1. It would seem essential that general surgery residents be well trained in these procedures, but what about more complicated procedures? There are important lessons for residents to learn by managing complex conditions, such as liver resections, pancreaticoduodenectomy, and aortic aneurysm repairs, even though most general surgery residency graduates will not perform these in practice. These operations do teach technical skills, allow residents to be prepared for unexpected findings at operations, and teach the clinical expertise necessary to provide postoperative care for critically ill patients that have physiologic disturbances of shock, sepsis, and respiratory failure. General surgeons in practice must be capable of making the initial diagnosis and management of a diverse set of surgical conditions and prompt referral to a subspecialist when appropriate.

Table 1 Most frequent procedures by general surgeons at time of ABS recertification

| Endoscopy (83) | |

| Colonoscopy | 58 |

| EGD | 25 |

| Hernia (56) | |

| Open inguinal | 27 |

| Ventral | 21 |

| Lap inguinal | 8 |

| Laparoscopic cholecystectomy | 55 |

| Laparoscopic appendectomy | 15 |

| Open appendectomy | 7 |

| Breast (50) | |

| Breast biopsy | 24 |

| Sentinel node biopsy | 9 |

| Segmental mastectomy and axillary node dissection | 6 |

| Stereotactic biopsy | 6 |

| Simple mastectomy | 5 |

| Open colectomy | 10 |

| Miscellaneous (26) | |

| Central line placement | 11 |

| Bariatric surgery | 8 |

| Thyroidectomy | 7 |

Abbreviation: EGD, esophagogastroduodenoscopy.

The American Board of Surgery annually publishes its Booklet of Information, which outlines the requirements for certification in surgery and states: “General surgery is a discipline that requires knowledge of and familiarity with a broad spectrum of diseases that may require surgical treatment. By necessity, the breadth and depth of this knowledge will vary by disease category. In most areas, the surgeon will be expected to be competent in diagnosing and treating the full spectrum of disease. However, there are some types of disease in which comprehensive knowledge and experience is not gained in the course of a standard surgical residency. In these areas the surgeon will be able to recognize and treat a select group of conditions within a disease category” [16].

Fundamental to the concept of training of general surgeons is an agreed upon set of diagnoses and conditions that general surgeons should be capable of managing. The American Board of Surgery has taken up that challenge by forming the Surgical Council on Resident Education (SCORE) [17]. In partnership with the American College of Surgeons, the American Surgical Association, the Association of Program Directors of Surgery, the Association for Surgical Education, the Residency Review Committee (RRC) for Surgery, and the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons, the SCORE Patient Care Outline has been developed and is available in the General Surgery Residency Patient Care Curriculum [18]. This curriculum offers a description of 713 conditions/diseases and operations/procedures that a general surgeon is expected to be competent to manage. The 28 patient-care and 13 medical-knowledge categories define the content areas for testing in the qualifying and certifying examinations of the American Board of Surgery. This definition of the scope of general surgery training and practice sets a foundation to determine a threshold for adequate general surgery training necessary before advanced subspecialty training.

Although there is a widespread agreement that general surgery residency needs to prepare graduates for practice, the competing objective is how to best prepare surgical residents for subspecialty training or fellowship after general surgery training. Plastic surgery decided more than two decades ago on an integrated training structure, in which medical students match into plastic surgery training directly from medical school. Although the traditional fellowship training after general surgery residency still exists, the integrated paradigm allows for the rotations and experiences to be selected specifically to train a plastic surgeon. Recently, vascular surgery and now cardiothoracic surgery have followed suit, and offer medical students the option of selecting a career path directly from medical school [19,20]. The initial experience of these integrated training paradigms has been successful, attracting high-caliber candidates, although there are no long-term outcomes available. It is unclear if other subspecialties of general surgery will or should opt for an integrated training structure.

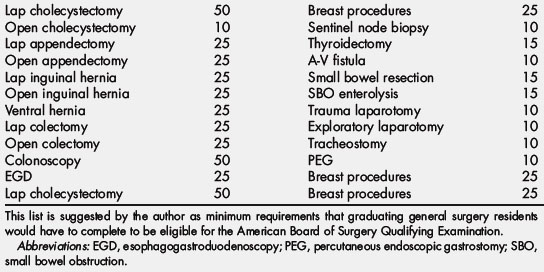

At the conclusion of the Residency Training Restructuring Committee’s deliberations, some modest recommendations were made and ultimately passed by the American Board of Surgery. The first recommendation was related to milestones that are being established by the ACGME to evaluate programs. In July 2002, the ACGME Outcome Project changed the currency of accreditation from process and structure (capturing a program’s potential to educate) to outcomes (capturing a program’s actual accomplishments). The SCORE committee has been charged to recommend milestones that the ACGME could use to evaluate as a measure of a program’s accomplishments. The ABS and RRC for Surgery have recommended that these program requirements may also be used by the American Board of Surgery as individual milestones for promotion during residency. Although no final selection of program or individual milestones have been made, Table 2 lists some of the requirements that have been discussed by the American Board of Surgery.

Table 2 Potential individual milestones for promotion

| PGY 1 | Completion of ACLS Completion of ACS/APDS Phase 1 modules Completion of ACS fundamentals course |

| PGY 2 | Passage of USMLE Part III Passage of ATLS Passage ABSITE junior basic science examination |

| PGY 3 | Completion of FLS Completion of SCORE prescribed modules Verification of competence by direct observation of two procedures (laparoscopic cholecystectomy and open inguinal hernia) |

| PGY 4 | Completion of ACS professionalism module Completion of ACS communication module Passage of ABSITE senior clinical examination |

| PGY 5 | Completion of a practice-based assessment |

Abbreviations: ABSITE, American Board of Surgery In-Training Examination; ACLS, advanced cardiac life support; ACS, American College of Surgeons; APDS, Association of Program Directors in Surgery; ATLS, advanced trauma life support; FLS, fundamentals of laparoscopic surgery; USMLE, United States Medical Licensing Examination.

The second recommendation was that additional flexibility should be allowed during the final years of general surgery residency. The Residency Review Committee has responded and will permit up to 6 months of focused experience in a primary component area. All requirements for categories of operative experience must still be met. In essence, this change will eliminate the requirement that every resident in a program must have the same experience. The change in projected resident operative experience was examined in a recent article that used a hypothetical model of allowing residents in 4 specialties (cardiothoracic surgery, pediatric surgery, colorectal surgery, vascular surgery) to begin their fellowship training 6 months earlier, and was found to increase the operative experience of general surgery residents in 9 index general surgery procedures by an average of 25% [21].

In the author’s opinion, the pathway to restructuring surgical residency training should begin by first defining what are the skills and expertise required to be a general surgeon and should be established by general surgery becoming a distinct subspecialty. The modern general surgeon will need to be skilled in managing the common diseases treated by general surgeons and should be an expert in their areas of practice, and training should be designed to provide that within the 5 years of general surgery training. In addition, they should be capable of establishing the initial diagnosis and management of complex conditions that require referral to other subspecialists. They must become the content expert in the management of alimentary tract (except liver, pancreas, esophagus), abdomen, breast disease, endocrine disease, and acute care surgery. The general surgeon should have expertise in minimally invasive surgery (perhaps except bariatric surgery), and receive adequate endoscopic training to be credentialed at the completion of training. These goals can best be accomplished by increasing the minimal operative requirements for completion of general surgery training, especially in laparoscopic colectomy, ventral and inguinal hernia repair, and upper and lower endoscopy. The American Board of Surgery could require that a minimum number of specific procedures be completed before being admitted to the ABS Qualifying Examination (Table 3). Although some have argued that it would be impossible to achieve these numbers during a general surgery residency, it would seem preferable to decide upon the skills necessary for practice and require the necessary experience. As the discipline of surgery is more than just a technical exercise, training requirements must also include preoperative evaluation, proper patient selection, and postoperative care.

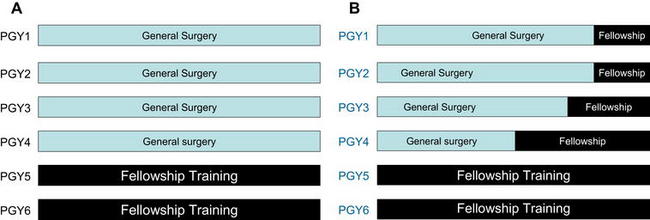

Other surgical subspecialties should have the option of delineating their optimal training structure. These pathways could incorporate integrated training that selects trainees directly from medical school, similar to plastic surgery, vascular surgery, and cardiothoracic surgery, or could choose to design modular pathways that incorporate a period of basic surgical training followed by early tracking into subspecialty training (Fig. 1).

References

[1] W.S. Halsted. The training of the Surgeon. Bulletin of Johns Hopkins Hospital. 1904;15:267-275.

[2] J.L. Cameron. William Stewart Halsted. Our surgical heritage. Ann Surg. 1997;225:445-458.

[3] B.N. Carter. The fruition of Halsted’s concept of surgical training. Surgery. 1952;32:518-527.

[8] G.S. Litynski. Endoscopic surgery: the history, the pioneers. World J Surg. 1999;23:745-753.

[10] AAMC: Physicians at teaching hospitals (PATH) audits. Available at: https://www.aamc.org/advocacy/teachphys/73578/teachphys_phys0040.html Accessed November 16, 2010

[13] J.E. Fischer. The impending disappearance of the general surgeon. JAMA. 2007;298:2191-2193.

[14] B.E. Stabile. The surgeon: a changing profile. Arch Surg. 2008;143:827-831.

[16] American Board of Surgery 2009–2010 Booklet of Information. Available at: http://home.absurgery.org/xfer/BookletofInfo-Surgery.pdf Accessed November 16, 2010

[17] Surgical Council on Resident Education General Surgery Residency Patient Care Curriculum Outline 2009–2010. Available at: http://www.surgicalcore.org/curriculumoutline2010-11.pdf Accessed November 16, 2010