180 Tick-Borne Diseases

• Many patients with tick-borne diseases (TBDs) do not recall a tick bite; the history should focus on activities that predispose to tick exposure.

• Because some of the TBDs are fatal if untreated, consider these diseases in patients with fever of unknown source, especially in “tick season.”

• TBDs most often can be strongly suspected or diagnosed clinically, and treatment should be initiated before definitive laboratory confirmation.

Epidemiology

Because these illnesses frequently occur in the absence of a known tick bite, physicians must consider TBDs when patients present in the correct epidemiologic context and with a recognizable syndrome. This chapter considers these diseases in syndromic groups (patterns of presentation), rather than individually. Individual TBDs are listed in Table 180.1 (North America) and Table 180.2 (worldwide). Travelers may import the TBDs from one location to another.

| DISEASE | PATHOGEN OR AGENT | MAJOR TICK VECTOR |

|---|---|---|

| Lyme disease | Borrelia burgdorferi | Ixodes scapularis, others |

| Babesiosis | Babesia microti | Ixodes scapularis |

| Anaplasmosis, granulocytic | Anaplasma phagocytophilum | Ixodes scapularis |

| Anaplasmosis, monocytic | Ehrlichia chaffeensis | Amblyomma americanum |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Rickettsia rickettsiae | Dermacentor variabilis |

| Tularemia | Francisella tularensis | Dermacentor variabilis, Dermacentor andersoni, and Amblyomma americanum |

| Relapsing fever | Borrelia species (various) | Ornithodoros species |

| Colorado tick fever | Coltivirus | Dermacentor andersoni |

| Tick paralysis | Neurotoxin | Dermacentor variabilis, others |

| Q fever | Coxiella burnetii | Dermacentor variabilis |

Table 180.2 Other Important Tick-Borne Diseases Worldwide

| DISEASE | PATHOGEN OR AGENT | MAJOR TICK VECTOR |

|---|---|---|

| Mediterranean spotted fever | Rickettsia conorii | Rhipicephalus sanguineus |

| Other spotted fevers | Other rickettsial species | Varies |

| Tick-borne encephalitis | Flavivirus | Ixodes ricinus, others |

| Relapsing fever | Various Borrelia species | Various Ornithodoros species |

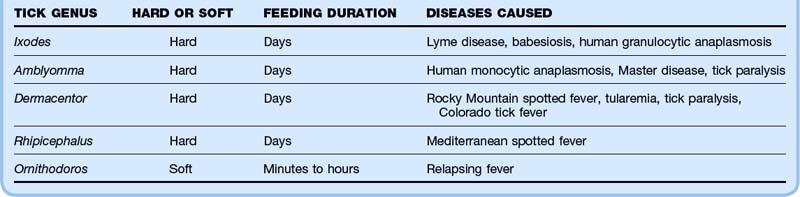

Pathophysiology and Tick Anatomy

Two families of ticks are important in human TBDs. Hard (Ixodidae) ticks tend to attach and feed for days, whereas soft ticks (Argasidae) feed in minutes to hours. Table 180.3 lists some characteristics of these different types of ticks. Because the hard ticks, which transmit most of the human TBDs, feed for so long, tick removal during the first 24 hours of attachment provides one strategy for disease prevention, a concept best studied in the context of Lyme disease. Figures 180.1 to 180.3 show various stages of Ixodes scapularis, Dermacentor variabilis, and Amblyomma americanum ticks.

Fig. 180.2 A Dermacentor variabilis tick next to an Ixodes scapularis tick.

(Photograph by Darlyne Murawski.)

Presenting Signs and Symptoms

TBDs most commonly manifest as one of four syndromes (Table 180.4):

| SYNDROME | DISEASE | CHARACTERISTICS OF TYPICAL CASES |

|---|---|---|

| Localized rash (without or without fever) | Erythema migrans (Lyme disease) Tularemia (ulceroglandular) |

Large, flat, red rash, sometimes with central clearing at the site of the tick bite Shallow ulcer, usually acral at the site of the tick bite, associated with regional lymphadenopathy |

| Febrile illness without rash | Anaplasmosis Babesiosis Lyme disease Rocky Mountain spotted fever Tularemia Q fever Colorado tick fever |

High fever, chills, headache, myalgias High fever, chills, headache, fatigue, myalgias Flulike illness without respiratory or gastrointestinal manifestations Severe headache, fever, myalgias High fever without localizing findings except respiratory symptoms in tularemic pneumonia Nonspecific febrile illness Fever (saddle-back curve), headache, myalgias |

| Febrile illness with generalized rash | Rocky Mountain spotted fever Lyme disease Anaplasmosis |

As above with rash; rash beginning as maculopapular, then possibly evolving into petechial and skin necrosis Multiple erythema migrans lesions (smaller, no punctum, less complexity than primary erythema migrans lesions) Nonspecific maculopapular rash |

| Acute neurologic illness | Tick paralysis | More commonly in children, especially in young girls with the tick embedded in the scalp |

Localized Rash (With or Without Fever)

Erythema migrans (EM), the rash of early localized Lyme disease, is an important condition that emergency physicians should be familiar with because antibiotic treatment at this stage almost always leads to excellent outcomes. Lyme disease is by far the most common vector-borne illness in North America. EM develops at the site of the tick bite roughly 7 to 10 days later (range, 3 to 33 days), usually as flat erythema that is neither pruritic nor painful, although it can be either. The classic description of a target or bull’s-eye lesion with central clearing is not the most common. Most EM rashes are uniformly red. EM can be darker in the center, vesicular, or necrotic. Know the spectrum of morphology of EM to avoid misdiagnosis of this infection (Figs. 180.4 to 180.6).

Although EM has always been thought to be pathognomonic of Lyme disease, EM-like lesions have been reported in the southeastern and central states; this has been called Master disease or southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI).1 Although these patients’ rashes have some differences from classic EM in patients from Lyme-endemic states, significant overlap can occur in individual patients. Other novel Borrelia species may cause this lesion, and these patients should also be treated with antibiotics, similar to patients with Lyme disease.

Febrile Illness with Generalized Rash

Many TBDs can manifest with fevers in which a generalized rash is a prominent manifestation of the illness. RMSF is the most dramatic of these illnesses; patients present with fever, headache, myalgias, and rash. The classic triad of fever, headache, and rash in a patient with a recent tick bite is seen in a few patients. Even with the larger tick vector, only approximately two thirds of patients recall the tick bite. In addition, the rash of RMSF does not develop until the third to the sixth day of the illness. The rash begins as a maculopapular rash that becomes petechial and finally may evolve into frank ecchymosis. The classic description of a rash that begins acrally and spreads centrally does not always apply. Thus, the rash can vary from nonexistent to frank skin necrosis. Because the organisms cause small vessel vasculitis, the manifestations are based on the particular organs affected. Patients can present with a surgical abdomen, an illness resembling meningitis, myocarditis, renal failure, or circulatory collapse. Untreated, RMSF has a mortality rate of 25% to 40%. Therefore, considering this diagnosis in any febrile patient with the correct epidemiologic context is important, because early antibiotic treatment reduces the mortality rate to less than 5%.2

Acute Weakness

The one TBD that is not caused by an infectious agent is tick paralysis. This illness can be caused by several tick species that produce neurotoxins. Patients present with gait instability, acute ascending weakness, and sometimes cranial nerve findings that suggest Guillain-Barré syndrome.3 Children, often girls with long hair, are more frequently affected, and the scalp of these patients must be very carefully inspected. The diagnosis is established by finding an engorged tick, the removal of which is also the treatment of this rare disease.

Other Manifestations of Lyme Disease

Lyme disease has been traditionally divided into three phases (Table 180.5). Early localized disease is characterized by EM, although some authors include flulike illness in this stage. Early disseminated disease typically involves the skin, heart, joints, and nervous system. Late disseminated disease generally affects the joints, nervous system, and (in Europe) the skin. Although early disseminated Lyme disease has many potential manifestations, the common and important manifestations for emergency physicians are cranial nerve palsy, meningitis, carditis, and arthritis.

Table 180.5 Common Manifestations and Treatment of Lyme Disease

| STAGE | MANIFESTATION | TREATMENT |

|---|---|---|

| Early localized | Localized erythema migrans | Oral amoxicillin, doxycycline, or cefuroxime axetil for 10-30 days |

| Mild early disseminated | Disseminated erythema migrans Conjunctivitis Early arthritis Seventh nerve palsy with normal cerebrospinal fluid Carditis with PR interval <0.30 |

Ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or penicillin G for 21-30 days |

| Severe early disseminated | Early neurologic manifestations with abnormal cerebrospinal fluid* Carditis with PR interval >0.30 or higher degrees of heart block |

Ceftriaxone, cefotaxime, or penicillin G for 2-3 wk |

| Late disseminated | Late neurologic manifestations (encephalopathy, peripheral neuropathy) Lyme arthritis |

Intravenous antibiotics for 2-4 wk Oral antibiotics for 30-60 days |

* Manifestations include cranial neuropathy, lymphocytic meningitis (with or without radiculitis or plexitis), transverse myelitis, and cerebellitis. Controversy exists regarding parenteral antibiotics if seventh nerve palsy is the only manifestation (and cerebrospinal fluid pleocytosis).

Any cranial nerve can be affected, but seventh nerve palsy is by far the most common. Bilateral facial involvement is not uncommon in patients with Lyme-induced facial palsy. Controversy exists regarding the appropriateness of lumbar puncture in these patients. The major question is this: Should the presence of pleocytosis mandate parenteral therapy or not? Although this question has no definitive answer, many physicians favor lumbar puncture and treat the patient parenterally if the cerebrospinal fluid shows abnormalities. A European study suggested that this approach is not necessary.4 Lyme meningitis, which can occur with or without other neurologic abnormalities, can be surprisingly “quiet” with respect to symptoms. Headache may be mild and intermittent, and meningeal signs are often absent.

Differential Diagnosis and Medical Decision Making

The differential diagnosis in these patients depends on the specific presenting syndrome and is largely covered in the previous section. A complete differential diagnosis of EM includes various other acute rashes.1 Physicians should diagnose early localized Lyme disease and tick paralysis by history and physical examination. Fifty percent of patients with EM have a negative Lyme serologic test result; therefore, no testing is necessary because a negative result should not dissuade the physician from diagnosing EM and treating it. Serologic testing is not indicated in most patients with EM.

The differential diagnosis of undifferentiated fever is enormous and includes just about every cause of fever. In patients with fever and generalized rash, one must consider bacteremia and viremia, especially meningococcemia and streptococcal and staphylococcal sepsis. Physicians should also treat suspected RMSF empirically without waiting for diagnostic test confirmation. Table 180.6 gives clues to the diagnosis of TBDs.

Table 180.6 Clinical Clues (History, Physical Examination, or Laboratory) Suggesting the Diagnosis of a Tick-Borne Illness Manifesting as a Nonspecific Febrile Illness*

| DISEASE | CLUES |

|---|---|

| Anaplasmosis | Faint rash possible Low white blood cell or platelet count Elevated hepatic transaminases |

| Babesiosis | Findings of hemolysis History of splenectomy Presence of faint rash, hepatomegaly, or splenomegaly |

| Lyme disease | Careful skin examination for any rash consistent with erythema migrans Bradycardia from heart block Associated seventh nerve palsy or lymphocytic meningitis |

| Colorado tick fever | Saddle-back fever curve |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever | Maculopapular or petechial rash Normal white blood cell count or low platelet count Hyponatremia Peripheral edema |

| Relapsing fever | Recurring episodes of fever with afebrile intervals |

| Tularemia | Acrally located ulcer Regional lymphadenopathy Possible associated pneumonia |

* Apart from an epidemiologic context suggesting a tick-borne disease.

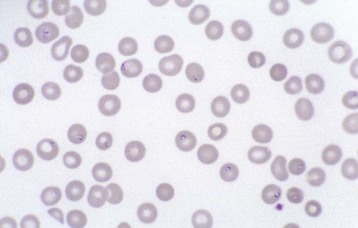

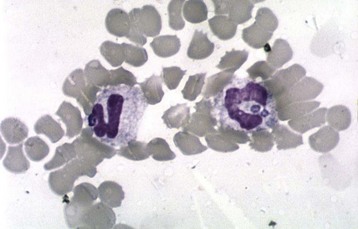

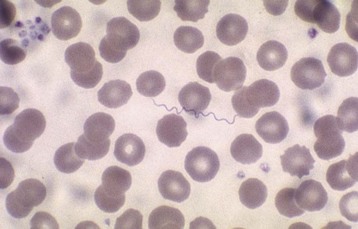

Physicians can often confidently diagnose babesiosis (Fig. 180.7), anaplasmosis (Fig. 180.8), and relapsing fever (Fig. 180.9) on the basis of a blood smear. Although numerous antigen and antibody tests are available for all these diseases, the results of these tests are hardly ever available in real time.

Fig. 180.8 Blood smear showing a morula in a patient with anaplasmosis.

(Courtesy of Dr. J. S. Dumler.)

Fig. 180.9 Blood smear showing relapsing fever Borrelia.

This blood smear shows a spirochete in the blood from a patient with relapsing fever.

Tips and Tricks

• Most patients with Lyme disease and approximately one third of patients with Rocky Mountain spotted fever (for which the tick vector is much larger) do not have a history of a known tick bite.

• Treat patients with presumed Rocky Mountain spotted fever with a tetracycline even if a rash is not yet present.

• Remember that up to 20% of patients with tick-borne disease have more than one infection transmitted by the same tick bite.

• Examine the whole body, and particularly the scalp, in all patients presenting with acute significant weakness or a clinical picture resembling Guillain-Barré syndrome. This is especially important in young children and occurs most often in young girls.

• In early localized Lyme disease with erythema migrans, serologic testing is not indicated or helpful, unless the clinical findings and situation are very atypical or ambiguous. Serologic test results are normal approximately 50% of the time.

• In children, even those younger than 9 years of age, with life-threatening cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever or anaplasmosis, use intravenous doxycycline initially.

Treatment

Table 180.5 shows the treatments for specific manifestations of Lyme disease. Treat patients with the remaining bacterial TBDs with specific antimicrobial therapy (Table 180.7). Data suggest a trend toward shorter courses of antibiotics in patients with early Lyme disease.5,6

| DISEASE | ANTIMICROBIAL TREATMENT | OTHER ISSUES |

|---|---|---|

| Anaplasmosis (formerly called ehrlichiosis) | Doxycycline | Even in children, IV doxycycline indicated |

| Babesiosis | Clindamycin and quinine Atovaquone and azithromycin |

In severely affected patients, consider exchange transfusion |

| Rocky Mountain spotted fever (and other rickettsial spotted fevers) | Doxycycline or chloramphenicol. | Even in children, IV doxycycline indicated |

| Relapsing fever | Doxycycline | Some patients with carditis require a temporary pacemaker |

| Tularemia | Streptomycin, gentamicin, or doxycycline | |

| Q fever | Doxycycline | |

| Tick paralysis | None | Tick removal constitutes treatment; ICU observation often necessary |

| Colorado tick fever, tick-borne encephalitis | None | Supportive care |

ICU, Intensive care unit; IV, intravenous.

* The choices of antibiotics, route, dose, and duration should be made on a case-by-case basis, depending on the severity of illness, allergies, age of patient, pregnancy, and other individual factors.

Follow-Up, Next Steps, and Patient Education

Anderson JF. The natural history of ticks. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:205–218.

Borg R, Dotevall L, Hagberg L, et al. Intravenous ceftriaxone compared with oral doxycycline for the treatment of Lyme neuroborreliosis. Scand J Infect Dis. 2005;37:449–454.

Dattwyler RJ, Luft BJ, Kunkel MJ, et al. Ceftriaxone compared with doxycycline for the treatment of acute disseminated Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:289–294.

Demma LJ, Traeger MS, Nicholson WL, et al. Rocky Mountain spotted fever from an unexpected tick vector in Arizona. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:587–594.

Edlow JA. Erythema migrans. Med Clin North Am. 2002;86:239–260.

Edlow JA. Lyme disease and related tick-borne illnesses. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;33:680–693.

Klempner MS, Hu LT, Evans J, et al. Two controlled trials of antibiotic treatment in patients with persistent symptoms and a history of Lyme disease. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:85–92.

Krause PJ, Telford SR, 3rd., Spielman A, et al. Concurrent Lyme disease and babesiosis: evidence for increased severity and duration of illness. JAMA. 1996;275:1657–1660.

Masters EJ, Olson GS, Weiner SJ, Paddock CD. Rocky Mountain spotted fever: a clinician’s dilemma. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:769–774.

Nadelman RB, Nowakowski J, Fish D, et al. Prophylaxis with single-dose doxycycline for the prevention of Lyme disease after an Ixodes scapularis tick bite. N Engl J Med. 2001;345:79–84.

Philipp MT, Wormser GP, Marques AR, et al. A decline in C6 antibody titer occurs in successfully treated patients with culture-confirmed early localized or early disseminated Lyme borreliosis. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1069–1074.

2008 Tick-borne diseases, part I: Lyme disease. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 22(2), 2008. [entire issue]

2008 Tick-borne diseases, part II. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 22(3), 2008. [entire issue]

1 Tibbles CD, Edlow JA. Does this patient have erythema migrans? JAMA. 2007;297:2617–2627.

2 Kirkland KB, Wilkinson WE, Sexton DJ. Therapeutic delay and mortality in cases of Rocky Mountain spotted fever. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;20:1118–1121.

3 Edlow JA. Tick paralysis. Curr Treat Options Neurol. 2010;12:167–177.

4 Liostad U, Skogvoll E, Eikeland R, et al. Oral doxycycline versus intravenous ceftriaxone for European Lyme neuroborreliosis: a multicentre, non-inferiority, double-blind, randomized trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:690–695.

5 Wormser GP, Ramanathan R, Nowakowski J, et al. Duration of antibiotic therapy for early Lyme disease: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138:697–704.

6 Kowalski TJ, Tata S, Berth W, et al. Antibiotic treatment duration and long-term outcomes of patients with early Lyme disease from a Lyme disease-hyperendemic area. Clin Infect Dis. 2010;50:512–520.