Thyroiditis

1. Give the differential diagnosis for thyroiditis.

Infectious: acute (suppurative), subacute (granulomatous, de Quervain’s)

Infectious: acute (suppurative), subacute (granulomatous, de Quervain’s)

Autoimmune: chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto’s disease), atrophic (primary myxedema), juvenile, postpartum

Autoimmune: chronic lymphocytic (Hashimoto’s disease), atrophic (primary myxedema), juvenile, postpartum

Drug-induced (certain medications, iodinated contrast material)

Drug-induced (certain medications, iodinated contrast material)

2. What causes acute thyroiditis?

This rare disease has an infectious etiology, most reported pathogens being Staphylococcus, Streptococcus, Pneumocystis carinii, and Mycobacterium species. Fungal, parasitic, or syphilitic infections have been reported, and immunocompromised patients may be at increased risk. Patients may demonstrate hypothyroid or hyperthyroid symptoms or may remain euthyroid. Rarely, metastatic disease to the thyroid gland can manifest as acute thyroiditis.

3. How is acute thyroiditis managed?

Treatment involves incision and drainage of the abscess or surgical excision and antimicrobials. Children often have a pyriform sinus fistula, which should be surgically repaired.

4. Describe the four stages of subacute thyroiditis.

Stage I: Patients have a painful (unilateral or bilateral) tender thyroid and may have systemic symptoms (fatigue, malaise, fever). Inflammatory destruction of thyroid follicles permits release of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) into the blood, and thyrotoxicosis may ensue.

Stage I: Patients have a painful (unilateral or bilateral) tender thyroid and may have systemic symptoms (fatigue, malaise, fever). Inflammatory destruction of thyroid follicles permits release of thyroxine (T4) and triiodothyronine (T3) into the blood, and thyrotoxicosis may ensue.

Stage II: A transitory period (several weeks) of euthyroidism occurs after the T4 is cleared from the body.

Stage II: A transitory period (several weeks) of euthyroidism occurs after the T4 is cleared from the body.

Stage III: With severe disease, patients may become hypothyroid until the thyroid gland repairs itself.

Stage III: With severe disease, patients may become hypothyroid until the thyroid gland repairs itself.

5. Summarize the natural history of subacute thyroiditis.

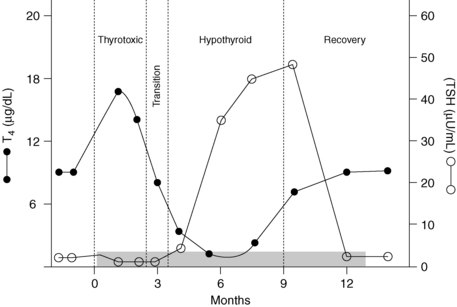

Subacute thyroiditis is probably viral in origin. Histologically, the inflammation is granulomatous. Although patients almost always recover clinically, serum thyroglobulin (Tgb) levels remain elevated, and intrathyroidal iodine content is low for many months (Fig. 35-1). Such findings suggest persistent subclinical abnormalities after an episode of subacute thyroiditis. Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory agents are first-line treatment in mild to moderate cases, whereas steroids may be needed when the condition is more severe. Patients requiring steroids are more likely to become hypothyroid at a later time. Up to 4% of patients have a second episode many years later.

6. What is the most common cause of thyroiditis?

Autoimmune thyroid disease, which is recognized by the presence of thyroid peroxidase (TPO) antibody and, less frequently, thyroglobulin antibody in serum.

7. Describe the clinical characteristics of autoimmune thyroid disease.

Chronic lymphocytic thyroiditis (Hashimoto’s disease) usually manifests as a euthyroid goiter that progresses to hypothyroidism in middle-aged and older persons, especially women. Atrophic thyroiditis is characterized by a very small thyroid gland in a hypothyroid patient. Some evidence suggests that thyroid growth–inhibitory antibodies may account for the lack of a goiter. Two thirds of adolescents with goiter have autoimmune (juvenile) thyroiditis.

8. Does postpartum thyroiditis follow a different clinical course from that of other types of autoimmune thyroiditis?

Yes. Postpartum disease develops in women between the third and ninth months after delivery, sometimes even 1 year postpartum. It typically follows the stages seen in patients with subacute thyroiditis, although histologically, patients with postpartum disease have lymphocytic infiltration.

9. How common is postpartum thyroiditis?

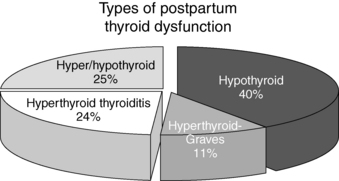

After delivery, 5% to 10% of women show biochemical evidence of thyroid dysfunction. Approximately one third of affected women have symptoms (either hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism, or both) and benefit from 6 to 12 months of therapy with levothyroxine (LT4) if they are hypothyroid. Up to 70% of patients experience recurrence with subsequent pregnancies. The frequency of each clinical presentation is depicted in Figure 35-2.

10. Which patients with postpartum thyroiditis should be treated?

Postpartum thyroiditis is a destructive process; therefore an antithyroidal drug (methimazole) is not effective. If hyperthyroid symptoms are present, beta-blockers can be used. Hypothyroid patients with severe symptoms and those who desire conception should receive treatment with LT4. In these cases, however, tapering off the medication should be tried 6 to 12 months after initiation, in the attempt to eventually discontinue therapy.

11. Summarize the differences between subacute and postpartum thyroiditis.

TABLE 35-1.

SUBACUTE VERSUS POSTPARTUM THYROIDITIS

| SUBACUTE THYROIDITIS | POSTPARTUM THYROIDITIS | |

| Thyroid pain | Yes | No |

| Erythrocyte sedimentation rate | Increased | Normal |

| Thyroid peroxidase antibody | Transient increase only | Positive |

| HLA status | B-35 | DR3, DR5 |

| Histology | Giant cells, granulomas | Lymphocytes |

12. Why does postpartum thyroiditis develop in some women?

Women in whom postpartum thyroiditis develops have underlying, usually asymptomatic, autoimmune thyroiditis. During pregnancy, the maternal immune system is partially suppressed, with a dramatic rebound rise in thyroid antibodies after delivery. Although TPO or thyroglobulin antibodies are not believed to be cytotoxic, they are currently the most reliable markers of susceptibility to postpartum disease.

13. Does thyroid function in patients with postpartum thyroiditis return to normal, as it does in subacute thyroiditis?

Not always. Approximately 20% of women become permanently hypothyroid, and a similar number have persistent mild abnormalities. An annual thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) measurement is therefore recommended.

14. Do any factors identify women at increased risk for the development of postpartum thyroiditis?

Women with a higher TPO antibody titer are more likely to have thyroiditis. Thyroiditis develops after delivery in approximately 25% of women with type 1 diabetes mellitus. For high-risk patients, screening for thyroid antibodies and careful monitoring of thyroid function at 3 to 6 months postpartum are indicated.

15. What is painless thyroiditis?

Both men and non-postpartum women may present with transient thyrotoxic symptoms. Like patients with subacute thyroiditis, they often experience subsequent hypothyroidism. Unlike subacute disease, this disorder is painless. It has been given a variety of names, including hyperthyroiditis, silent thyroiditis, transient painless thyroiditis with hyperthyroidism, and lymphocytic thyroiditis with spontaneously resolving hyperthyroidism. This disease was first described in the 1970s and reached its peak incidence in the early 1980s. It seems to occur less often now.

16. What causes painless thyroiditis?

Some investigators believe that it is a variant of subacute thyroiditis because a small percentage of patients with biopsy-proven subacute disease have had no pain (they may have fever and weight loss and may be mistaken for having systemic disease or malignancy). Others believe that it is a variant of Hashimoto’s disease because of similar histologic features. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis can occasionally manifest as thyroid pain; rarely, surgery is necessary to relieve symptoms.

17. What is destruction-induced thyroiditis?

Destruction-induced thyroiditis refers to disorders (subacute, postpartum, drug-induced, and painless thyroiditis) in which an inflammatory infiltrate destroys thyroid follicles and excessive amounts of T4 and T3 are released into the circulation.

18. When a patient presents with hyperthyroid symptoms, an elevated T4 value, and a suppressed TSH value, what test should be ordered next?

A 24-hour radioactive iodine uptake (RAIU) test should be performed. When the thyroid is overactive (as in Graves’ disease or toxic nodular disease), the RAIU value is elevated. In destruction-induced thyroiditis, the RAIU value is low, as a result of both suppression of TSH by the acutely increased level of serum T4 and the diminished ability of damaged thyroid follicles to trap and organify iodine.

19. What is the appropriate therapy for patients with any type of destructive thyroiditis?

In the thyrotoxic stage, beta-blockers relieve adrenergic symptoms. All forms of antithyroid therapy (drugs, radioactive iodine ablation, and surgery) are absolutely contraindicated. Analgesics (salicylates or prednisone) provide prompt relief of thyroid pain. Thyroid hormone relieves hypothyroid symptoms and should be continued for 6 to 12 months, depending on the severity of disease. Some patients require no therapy.

20. Which drugs can induce thyroiditis?

Amiodarone, an iodine-containing antiarrhythmic drug, may cause thyroid damage and thyrotoxicosis. Lithium therapy has been associated with granulomatous thyroiditis as well as with destructive thyroiditis without lymphocytic infiltration. Interferon-alpha (less commonly, interferon-beta) and interleukin-2 (e.g., denileukin diftitox, an antineoplastic agent that combines interleukin-2 with diphtheria toxin) can cause thyroiditis, and both hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism have occurred during therapy with these agents. Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (e.g., sunitinib, sorafenib) have been noted to cause hypothyroidism, potentially by causing destructive thyroiditis. Nonionic contrast materials (e.g., HEXABRIX) have been reported to cause destructive thyroiditis.

21. Does amiodarone induce only thyroiditis?

No. Because of the large amount of iodine in this drug, it can cause either iodine-induced hypothyroidism or hyperthyroidism. Distinguishing hyperthyroidism due to iodine excess (type 1 disease) from amiodarone-induced destructive thyroiditis (type 2 disease) can be difficult. Some differentiating features are listed in Table 35-2. Absence of blood flow on Doppler flow ultrasonography is particularly helpful in confirming type 2 disease.

TABLE 35-2.

TYPE 1 VERSUS TYPE 2 AMIODARONE INDUCED THYROIDITIS

| TYPE 1 | TYPE 2 | |

| Thyroid size | Goiter; nodules | Normal |

| Radioactive iodine uptake | ↓, normal, ↑ | ↓↓ |

| Thyroid antibodies | ↑, negative | Negative |

| Interleukin-6 | Normal, ↑ | ↑↑ |

| Doppler flow ultrasonography | ↑ | ↓ |

| Therapy | Antithyroid drugs, potassium perchlorate; thyroidectomy | Antithyroid drugs (?), steroids |

Riedel’s struma is a rare disorder in which the thyroid becomes densely fibrotic and hard. Local fibrosis of adjacent tissues may produce obstructive symptoms that require surgery. In some cases, fibrosis of other tissues (fibrosing retroperitonitis, orbital fibrosis, or sclerosing cholangitis) may occur.

Aizawa, T, Watanabe, T, Suzuki, N, et al, Radiation-induced painless thyrotoxic thyroiditis followed by hypothyroidism. a case report and literature review. Thyroid 1998;8:273–275.

Bogazzi, F, Bartalena, L, Martino, E. Approach to the patient with amiodarone-induced thyrotoxicosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95(6):2529–2535.

Carella, C, Mazziotti, G, Amato, G, et al, Clinical review 169. interferon-α-related thyroid disease pathophysiological, epidemiological, and clinical aspects. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2004;89:3656–3661.

Feldt, S, Schussel, K, Quinzler, R, et al, Incidence of thyroid hormone therapy in patients treated with sunitinib or sorafenib. a cohort study. Eur J Cancer 2012;48:974–981.

Hennessey, J, Riedel’s thyroiditis. a clinical review. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(10):3031–3041.

Jimenez-Heffernan, J, Perez, F, Hornedo, J, et al. Massive thyroid tumoral embolism from a breast carcinoma presenting as acute thyroiditis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004;128:804–806.

Kon, YC, DeGroot, LJ, Painful Hashimoto’s thyroiditis as an indication for thyroidectomy. clinical characteristics and outcome in seven patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2003;88:2667–2672.

Lazarus, J. Lithium and thyroid. Best Pract & Res Clin Endocr & Metab. 2009;23:723–733.

Meek, SE, Smallridge, RC. Thyroiditis and other more unusual forms of hyperthyroidism. In: Cooper DS, ed. Medical management of thyroid disease. New York: Informa Healthcare; 2008:101–144.

Nicholson, W, Robinson, K, Smallridge, R, et al, Prevalence of postpartum thyroid dysfunction. a quantitative review. Thyroid 2006;16:573–582.

Rotenberg, Z, Weinberger, I, Fuchs, J, et al. Euthyroid atypical subacute thyroiditis simulating systemic or malignant disease. Arch Intern Med. 1986;146:105–107.

Samuels, MH. Subacute, silent and postpartum thyroiditis. Med Clin N Am. 2012;96:223–233.

Smallridge, RC. Hypothyroidism and pregnancy. Endocrinologist. 2002;12:454–464.

Smallridge, RC, Postpartum thyroid disease. a model of immunologic dysfunction. Clin Appl Immunol Rev 2000;1:89–103.

Smallridge, RC, De Keyser, FM, Van Herle, AJ, et al, Thyroid iodine content and serum thyroglobulin. cues to the natural history of destruction-induced thyroiditis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 1986;62:1213–1219.

Stagnaro-Green, A, Abalovich, M, Alexander, E, et al. Guidelines of the American Thyroid Association for the diagnosis and management of thyroid disease during pregnancy and postpartum. Thyroid. 2011;21:1081–1125.

Yu, EH, Ko, W, Chuang, Y, et al, Suppurative Acinetobacter baumannii thyroiditis with bacteremic pneumonia. case report and review. Clin Infect Dis 1998;27:1286–1290.