Thyroid emergencies

Thyroid storm or crisis is a life-threatening condition characterized by an exaggeration of the manifestations of thyrotoxicosis. When thyroid storm was first described, the acute mortality rate was nearly 100%. Today, the prognosis is significantly improved if appropriate therapy is initiated early; however, the mortality rate continues to be approximately 20%.

2. How do patients develop thyroid storm?

Thyroid storm usually occurs in patients who have unrecognized or inadequately treated thyrotoxicosis and a superimposed precipitating event, such as thyroid surgery, nonthyroid surgery, infection, or trauma.

3. What are the clinical manifestations of thyroid storm?

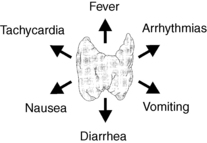

Fever (> 102° F) is the cardinal manifestation. Tachycardia is usually present, and tachypnea is common, but the blood pressure is variable. Cardiac arrhythmias, congestive heart failure, and ischemic heart symptoms may develop. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain are frequent features (Fig. 38-1). Central nervous system manifestations include hyperkinesis, psychosis, and coma. A goiter is a helpful finding but is not always present.

Figure 38-1. Symptoms of thyroid storm.

4. What laboratory abnormalities are seen in thyroid storm?

Serum thyroxine (total T4 and free T4) and triiodothyronine (total T3 and free T3) are usually significantly elevated, and serum thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH) is undetectable. These hormone levels, however, cannot reliably distinguish patients with thyroid storm from those who have uncomplicated thyrotoxicosis. Other common findings include anemia, leukocytosis, hyperglycemia, azotemia, hypercalcemia, and elevated liver enzymes.

5. How is the diagnosis of thyroid storm made?

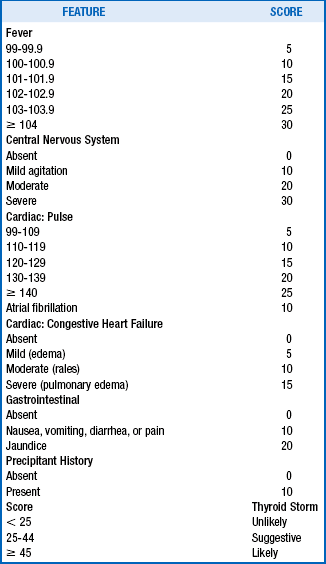

The diagnosis must be made on the basis of suspicious but nonspecific clinical findings. If the diagnosis is strongly suspected, waiting for the results of tests may cause a critical delay in the initiation of effective lifesaving therapy. Clinical features are therefore the key. Table 38-1 provides a useful scoring system to aid in diagnosis.

6. What other conditions may mimic thyroid storm?

7. How should patients with thyroid storm be treated?

The immediate goals are to decrease thyroid hormone synthesis, to inhibit thyroid hormone release, to reduce the heart rate, to support the circulation, and to treat the precipitating condition. Because beta1-adrenergic receptors are significantly increased in patients with this condition, beta1-selective blockers are the preferred agents for heart rate control.

8. What drugs are used to decrease thyroid hormone synthesis?

Propylthiouracil, 600 to 1200 mg daily (oral, rectal, or nasogastric [NG] tube)

Propylthiouracil, 600 to 1200 mg daily (oral, rectal, or nasogastric [NG] tube)

Methimazole, 60 to 120 mg daily (oral, rectal, NG tube, or intravenous [IV])

Methimazole, 60 to 120 mg daily (oral, rectal, NG tube, or intravenous [IV])

9. List drugs used to inhibit thyroid hormone release

Sodium iodide (NaI), 1 g over 24 hours (IV)

Sodium iodide (NaI), 1 g over 24 hours (IV)

10. What drugs are used to reduce the heart rate?

Esmolol, 500 mg over 1 minute, followed by 50 to 300 mg/kg/minute infusion (IV)

Esmolol, 500 mg over 1 minute, followed by 50 to 300 mg/kg/minute infusion (IV)

Metoprolol, 5 to 10 mg every 2 to 4 hours (IV)

Metoprolol, 5 to 10 mg every 2 to 4 hours (IV)

Diltiazem, 60 to 90 mg every 6 to 8 hours orally, or 0.25 mg/kg over 2 minutes, followed by infusion of 10 mg/minute (IV)

Diltiazem, 60 to 90 mg every 6 to 8 hours orally, or 0.25 mg/kg over 2 minutes, followed by infusion of 10 mg/minute (IV)

11. What other interventions are critical for resolution of thyroid storm?

Stress glucocorticoid doses (hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone)

Stress glucocorticoid doses (hydrocortisone, methylprednisolone, dexamethasone)

Identification and treatment of the underlying cause of thyroid storm

Identification and treatment of the underlying cause of thyroid storm

12. When traditional therapy fails, what additional options should be considered?

Plasma exchange and plasmapheresis can be lifesaving measures in patients with thyroid storm who have not adequately responded to the foregoing standard measures.

Myxedema coma is a life-threatening condition characterized by an exaggeration of the manifestations of hypothyroidism. Myxedema coma originally had a mortality rate of 100%. Today, the outlook is much improved for appropriately treated patients; the mortality rate in more recent studies has varied from 0% to 45%.

14. How do patients develop myxedema coma?

Myxedema coma usually occurs in older patients who have inadequately treated or untreated hypothyroidism and a superimposed precipitating event. Important events include prolonged cold exposure, infection, trauma, surgery, myocardial infarction, congestive heart failure, pulmonary embolism, stroke, respiratory failure, gastrointestinal bleeding, and administration of various drugs, particularly those with a depressive effect on the central nervous system.

15. What are the clinical manifestations of myxedema coma?

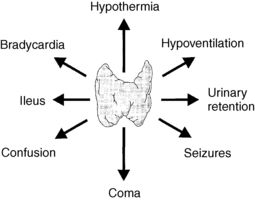

Hypothermia, bradycardia, and hypoventilation are common. Blood pressure, although generally reduced, is more variable. Pericardial, pleural, and peritoneal effusions are often found. Ileus is frequently present, and acute urinary retention may be seen. Central nervous system manifestations include seizures, stupor, and coma (Fig. 38-2). Deep tendon reflexes are absent or exhibit a delayed relaxation phase. Typical hypothyroid skin and hair changes are often apparent. A goiter, although frequently absent, is a helpful finding. A thyroidectomy scar may also be an important clue.

Figure 38-2. Symptoms of myxedema coma.

16. What laboratory abnormalities are seen in myxedema coma?

Serum T4 (total and free T4) and T3 (total and free T3) levels are usually low, and TSH is significantly elevated. Other frequent abnormalities include anemia, hyponatremia, hypoglycemia, and elevated serum levels of cholesterol and creatine kinase (CK). Arterial blood gases often reveal carbon dioxide retention and hypoxemia. The electrocardiogram often shows sinus bradycardia, various types and degrees of heart block, low voltage, and T-wave flattening.

17. How is the diagnosis of myxedema coma made?

The diagnosis must be made on clinical grounds on the basis of the findings described earlier. Serum levels of thyroid hormones are reduced and the TSH level is elevated, but the delay involved in waiting for test results may unnecessarily postpone the initiation of effective therapy.

18. How should patients with myxedema coma be treated?

The goals are to replace the depleted thyroid hormone pool rapidly, to replace glucocorticoids, to support vital functions, and to treat any precipitating conditions. The normal total body pool of T4 is about 1000 μg (500 μg in the thyroid, 500 μg in the rest of the body).

19. How are circulating thyroid hormones rapidly replaced?

Levothyroxine (LT4), liothyronine (LT3), or both may be used. The best regimen remains undetermined, but the combination of LT4 plus LT3 is recommended. Regimens for LT4 alone, LT3 followed by LT4, and LT4 plus LT3 are as follows:

LT4 alone: LT4, 200 to 300 μg over 5 minutes (IV), followed by 50 to 100 μg/day (oral or IV)

LT4 alone: LT4, 200 to 300 μg over 5 minutes (IV), followed by 50 to 100 μg/day (oral or IV)

LT3 followed by LT4: LT3, 50 to 100 μg over 5 minutes (IV), followed by LT4, 50 to 100 μg/day (oral or IV)

LT3 followed by LT4: LT3, 50 to 100 μg over 5 minutes (IV), followed by LT4, 50 to 100 μg/day (oral or IV)

LT4 plus LT3: LT4, 200 to 300 μg over 5 minutes plus LT3, 20 to 50 μg over 5 minutes (IV), followed by LT4, 50 to 100 μg/day, and LT3, 20 to 30 μg/day (oral or IV)

LT4 plus LT3: LT4, 200 to 300 μg over 5 minutes plus LT3, 20 to 50 μg over 5 minutes (IV), followed by LT4, 50 to 100 μg/day, and LT3, 20 to 30 μg/day (oral or IV)

20. What other interventions are critical for resolution of myxedema coma?

Brooks, MH, Waldstein, SS. Free thyroxine concentrations in thyroid storm. Ann Intern Med. 1980;93:694–697.

Burch, HD, Wartofsky, L, Life-threatening thyrotoxicosis. thyroid storm. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1993;22:263–278.

Dillmann, WH. Thyroid storm. Curr Ther Endocrinol Metab. 1997;6:81–85.

Fliers, E, Wiersinga, WM. Myxedema coma. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2003;4:137–141.

Jordan, RM, Myxedema coma. pathophysiology, therapy, and factors affecting prognosis. Med Clin North Am 1995;79:185–194.

Koball, S, Hickstein, H, Gloger, M, et al, Treatment of thyrotoxic crisis with plasmapheresis and single pass albumin dialysis. a case report. Artif Organs 2010;34:E55–E58.

Kokuho, T, Kuji, T, Yasuda, G, Umemura, S. Thyroid storm induced multiple organ failure relieved quickly by plasma exchange therapy. Ther Apher Dial. 2004;8:347–349.

Nicoloff, JT, Myxedema coma. a form of decompensated hypothyroidism. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 1993;22:279–290.

Pittman, CS, Zayed, AA. Myxedema coma. Curr Ther Endocrinol Metab. 1997;6:98–101.

Rodriguez, I, Fluiters, E, Perez-Mendez, LF, et al. Severe mental impairment and poor physiologic status are associated with mortality in myxedema coma. J Endocrinol. 2004;180:347–350.

Sarlis, NJ, Gourgiotis, L. Thyroid emergencies. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2003;4:129–136.

Tietgens, ST, Leinung, MC. Thyroid storm. Med Clin North Am. 1995;79:169–184.

Tsitouras, PD. Myxedema coma. Clin Geriatr Med. 1995;11:251–258.

Yamamoto, T, Fukuyama, J, Fujiyoshi, A, Factors associated with mortality of myxedema coma. report of eight cases and literature survey. Thyroid 1999;9:1167–1174.

Yeung, S-CJ, Go, R, Balasubramanyam, A. Rectal administration of iodide and propylthiouracil in the treatment of thyroid storm. Thyroid. 1995;5:403–405.