Thyroid

Appraise

1. Indications for thyroid surgery fall into three categories:

Suspected or proven malignancy

Suspected or proven malignancy

Graves’ disease (named after the Irish physician Robert James Graves, who described a case of goitre with exophthalmos in 1835. In Europe the condition is named after Karl von Basedow).

Graves’ disease (named after the Irish physician Robert James Graves, who described a case of goitre with exophthalmos in 1835. In Europe the condition is named after Karl von Basedow).

2. All thyroid surgery carries significant potential morbidity. Carefully investigate patients about to undergo surgery and involve the multidisciplinary team to avoid inappropriate or unnecessary surgery. Thyroid surgery is a significant potential source of litigation. As well as counselling your patient, provide clear documentation, especially with regard to potential damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve and the parathyroid glands.

3. Thyroid surgery is increasingly performed in specialist centres by surgeons with a special interest in thyroid disorders. Closely liaise with endocrinologists and oncologists to achieve satisfactory outcomes. Joint or combined clinics are advocated, particularly for patients with complex disease.

4. It is mandatory to have access to and attend an appropriate multidisciplinary team meeting (MDT) if you regularly undertake malignant thyroid surgery. Familiarize yourself with local arrangements.

5. Be willing to work jointly with other surgical specialists, such as cardiothoracic surgeons, when treating retrosternal extensions.

6. Re-operation in the neck carries significantly increased morbidity. As a result, partial or subtotal thyroidectomy is now less frequently performed in favour of either hemi- or total thyroidectomy. The aim is to leave behind as little thyroid tissue as possible.

7. Audit your results personally, locally and nationally. In the UK results are submitted to the British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons (BAETS).1 The Association publishes audit results and guidelines for managing thyroid disease. Familiarize yourself with the website www.baets.org.uk.

8. Assessment (see Table 20.1).

Table 20.1

| Ask yourself: | History | Examination |

| Is the patient euthyroid? | Intolerance to heat and cold, weight loss, altered bowel habit, anxiety/depression | Tachycardia, tremor, Graves’ eye signs, skin changes |

| What kind of goitre is this? | Physiologic, toxic | Diffuse, solitary nodule, multinodular |

| Is a malignant process likely? | Neck pain, hoarseness, family history of thyroid cancer, previous exposure to radiation | Lymph nodal masses, recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy, fixation, Berry’s sign (loss of carotid pulsation indicating invasion by tumour) |

| Does the patient have obstruction? | Dysphagia, shortness of breath, inability to lay flat |

Stridor, venous engorgement, Pemberton’s sign (Hugh Pemberton, 1946) – facial flushing on raising both arms indicating SVC obstruction |

| Can the goitre be delivered through the neck? | Longstanding goitre, significant obstructive symptoms |

Retrosternal extension |

Biochemical evaluation is mandatory in patients with thyroid disease. Familiarize yourself with and check thyroid function tests (tri-iodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4) and thyroid stimulating hormone: TSH), as well as calcium and albumin assays, prior to considering surgery. Undiagnosed or unrecognized thyrotoxicosis can lead to serious consequences during general anaesthesia. Vitamin D levels may be assayed in areas where deficiency is endemic and corrected prior to surgery. Thyroid auto-antibodies may also be requested to screen for the presence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (first described by Japanese physician Hashimoto Hakaru in Germany in 1912).

Biochemical evaluation is mandatory in patients with thyroid disease. Familiarize yourself with and check thyroid function tests (tri-iodothyronine (T3), thyroxine (T4) and thyroid stimulating hormone: TSH), as well as calcium and albumin assays, prior to considering surgery. Undiagnosed or unrecognized thyrotoxicosis can lead to serious consequences during general anaesthesia. Vitamin D levels may be assayed in areas where deficiency is endemic and corrected prior to surgery. Thyroid auto-antibodies may also be requested to screen for the presence of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis (first described by Japanese physician Hashimoto Hakaru in Germany in 1912).

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is an efficient and cost-effective method of evaluating thyroid nodules. Diagnostic accuracy is dependent on the experience of the operator, the position and type of nodule and the experience of the cytologist. Increasingly, FNAC is performed under ultrasound guidance which can be particularly beneficial in complex cysts and nodules deep within the gland. Having access to a cytologist and radiologist in the thyroid clinic (‘one-stop’ clinic), can lead to increased diagnostic accuracy (Box 20.1).

Fine needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) is an efficient and cost-effective method of evaluating thyroid nodules. Diagnostic accuracy is dependent on the experience of the operator, the position and type of nodule and the experience of the cytologist. Increasingly, FNAC is performed under ultrasound guidance which can be particularly beneficial in complex cysts and nodules deep within the gland. Having access to a cytologist and radiologist in the thyroid clinic (‘one-stop’ clinic), can lead to increased diagnostic accuracy (Box 20.1).

Ultrasound scanning (USS) is the radiological investigation of choice for the thyroid nodule. It can be used in isolation or in conjunction with FNAC. It is increasingly used in the diagnosis and follow-up of thyroid nodules and can give important prognostic information.

Ultrasound scanning (USS) is the radiological investigation of choice for the thyroid nodule. It can be used in isolation or in conjunction with FNAC. It is increasingly used in the diagnosis and follow-up of thyroid nodules and can give important prognostic information.

Computed tomography (CT) is of particular use in staging of patients with proven malignant disease as well as patients with benign disease with obstructive symptoms. CT can accurately assess tracheal compression, retrosternal extension and aid in the planning of access surgery that may require a thoracotomy.

Computed tomography (CT) is of particular use in staging of patients with proven malignant disease as well as patients with benign disease with obstructive symptoms. CT can accurately assess tracheal compression, retrosternal extension and aid in the planning of access surgery that may require a thoracotomy.

Barium swallow enables you to assess the extent to which a patient’s dysphagia can be attributed to extrinsic compression of the oesophagus by a goitre.

Barium swallow enables you to assess the extent to which a patient’s dysphagia can be attributed to extrinsic compression of the oesophagus by a goitre.

Pulmonary function tests may give information regarding breathlessness related to tracheal compression.

Pulmonary function tests may give information regarding breathlessness related to tracheal compression.

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can be useful in the management of suspected recurrent malignant disease. Anatomic detail is improved when used in conjunction with CT (PET-CT).

Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning can be useful in the management of suspected recurrent malignant disease. Anatomic detail is improved when used in conjunction with CT (PET-CT).

10. Indications for surgery in nodular thyroid disease:

Clinical suspicion of malignancy regardless of FNAC

Clinical suspicion of malignancy regardless of FNAC

Repeatedly non-diagnostic cytology (Thy 1)

Repeatedly non-diagnostic cytology (Thy 1)

Indeterminate or follicular cytology (Thy 3)

Indeterminate or follicular cytology (Thy 3)

11. Your decision to recommend surgery should be based on clinical assessment in conjunction with the FNAC result and findings on imaging studies.

Prepare

It is essential to warn the patient about the risks of surgery:

1. Laryngeal nerve damage. Recurrent laryngeal nerve damage leads to a weak breathy voice and poor cough, typically described as bovine. Discuss with the patient the risk of temporary (5%) and permanent (0.5–1%) damage to the recurrent laryngeal nerve. Neuraopraxias may take several months to resolve. Referral to a voice therapist may be indicated. For patients with permanent damage, vocal cord medialization procedures may be indicated. Damage to the external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve may lead to subtle changes in voice (typically loss of high-pitched phonation). This is most evident to professional voice users and singers. Always record vocal cord function and occupation preoperatively.

2. Hypocalcaemia. Temporary hypocalcaemia occurs in up to 25% of patients following total thyroidectomy. It may be higher in patients with Graves’ disease or those with vitamin D deficiency. Permanent hypocalcaemia (requiring replacement with vitamin D and calcium) occurs in 2–5% of cases.

3. Haematoma. Haematoma rate is approximately 1%. It is higher in recurrent surgery.

4. Wound infection. Occurs in less than 1%.

5. Poor cosmesis. Hypertrophic or keloid scar formation can lead to an unsightly scar. Patients with a history of keloid formation should be counselled appropriately. You should consider using steroid injections and meticulous closure to minimize the risk.

MANAGEMENT OF THE SOLITARY THYROID NODULE AND THE DOMINANT NODULE WITHIN A MULTINODULAR GOITRE

1. Nodules within the thyroid gland are common, especially in women. Most are benign colloid nodules and/or cysts. The most common neoplasm of the thyroid gland is the thyroid adenoma. Importantly, follicular adenomas cannot be distinguished from carcinomas on the basis of cytology and as such require further diagnostic evaluation.3

2. Thyroid cancer is rare: the incidence is increasing, but in spite of this there is no corresponding increase in mortality. Much of the increase can be explained by subclinical malignant disease detected on routine scanning (‘incidentalomas’). Where incidence has increased, 89% of new disease manifests as tumours less than 2 cm in size.5

3. The solitary nodule in a euthyroid patient is the most common presentation of thyroid cancer. The malignant risk is independent of nodule size and it ranges between 10 and 20%.6 The risk of a thyroid nodule being malignant is higher in extremes of age, in males and in those previously exposed to ionizing radiation. Incidental nodules found on PET scanning carry a 30% malignant risk (Box 20.2).5

4. Hemithyroidectomy (removal of lobe and isthmus) is the procedure of choice for the solitary thyroid nodule. Cytology is by no means definitive and as such some suspicious lesions will turn out to be benign. There are instances where a total thyroidectomy may be offered but these cases should be discussed at the MDT prior to surgery.

MANAGEMENT OF MALIGNANT THYROID DISEASE

1. Well-differentiated thyroid cancer (papillary and follicular) makes up the majority of cancers of the thyroid gland. By far the commonest is papillary carcinoma, which accounts for approximately 80% of cases.2 It tends to occur in a younger age group than other thyroid cancers, with mean age at onset 40–45 years. It is often associated with micro and macro metastasis to cervical lymph nodes. The main risk factor for papillary thyroid cancer is ionizing radiation. The prognosis of papillary cancer is good, with 95% survival at 10 years.

2. Follicular carcinoma comprises 10–15% of carcinomas and has a mean age of onset in the 6th decade. It has a good prognosis, although slightly less favourable than papillary.

3. Medullar cancer is a malignancy of parafollicular C cells and makes up 5% of thyroid cancers. It is associated with multiple endocrine neoplasia syndrome (MEN IIa, MEN IIb), which has autosomal dominant inheritance. The RET proto-oncogene is implicated in MEN II and patients with medullary cancer and their relatives should be screened for this genetic mutation. Rule out phaeochromocytoma prior to surgical intervention.

4. Anaplastic (poorly differentiated) thyroid cancer is rare and carries a very poor prognosis. It typically presents with a rapidly expanding mass, often in an older patient. It progresses rapidly to airway compromise and death. Surgery is not indicated and most patients succumb to their disease within 3 months. The differential diagnosis is of thyroid lymphoma, which is eminently treatable: open biopsy may be needed to establish the diagnosis.

5. Treatment of choice for well-differentiated thyroid carcinoma is total thyroidectomy with central compartment nodal clearance. Most patients with papillary or follicular carcinoma then have ablative treatment with radioactive iodine therapy. Once all thyroid tissue is ablated, thyroglobulin can be used as a sensitive marker of recurrence.

MANAGEMENT OF GRAVES’ THYROTOXICOSIS

1. Graves’ disease demands a multidisciplinary team approach. An endocrinologist, a specialist in nuclear medicine, surgeon and anaesthetist should be involved if surgery is being considered. Treatment options include antithyroid drugs, beta-blocking drugs and radioactive iodine ablation. Surgery is often only recommended when these treatments have failed or were not tolerated by the patient.

2. Surgery may be the preferred option, for example in women planning a family who wish to avoid radioiodine treatment. Preoperatively, discuss the operative risks, including increased rates of hypocalcaemia. You should emphasize that eye signs, such as exophthalmos associated with Graves’ disease, may not regress postoperatively. Rarely, in the short term, they may worsen.

3. Total thyroidectomy is the surgical treatment of choice for patients with thyrotoxicosis. Performing subtotal thyroidectomy runs the risk of recurrent disease. Re-operation carries significantly increased risks, therefore consider total thyroidectomy in younger patients where lifetime risk of recurrent disease is higher.

4. Prepare by rendering patients euthyroid with antithyroid drugs such as carbimazole, adjusting the dose for each patient. Alternatively, institute a ‘block and replace’ regimen. Give large doses of antithyroid drugs and replace using T4, while giving beta-blocking drugs such as propranolol to reduce the risks of thyrotoxic crisis. Alternatively, give beta-blockers to overcome parasympathetic overactivity.

5. Lugol’s iodine (containing free iodine, named after the French physician), given orally 1 ml daily for 10 days preoperatively, reduces the vascularity of the gland at operation and in theory should reduce blood loss.

6. Anticipate and avoid life-threatening thyroid crisis by fully controlling thyrotoxicosis, which manifests with hyperpyrexia, tachycardia, agitation and respiratory distress. Manage within an intensive care unit with oxygen, beta-blocking drugs and sodium iodine.

MANAGEMENT OF BENIGN MULTINODULAR THYROID DISEASE

1. Multinodular goitre on its own is not an indication for surgery. Decide to what extent symptoms can be explained by the goitre. Breathlessness or dysphagia may have causes that warrant investigation.

2. Multinodular goitres can have significant extension into the superior mediastinum and in rare cases may be difficult or impossible to deliver through the neck. Rarely, in cases with significant retrosternal component, a sternal split or lateral thoracotomy may be required.

3. Treatment of choice is a hemithyroidectomy or total thyroidectomy, depending on the nature of the goitre and the patient’s symptoms.

4. Tracheomalacia (Greek: malakos = soft) may develop after removal of a longstanding goitre, although some doubt its existence. Discuss it with your anaesthetist preoperatively. The patient may require prolonged intubation or tracheostomy.

THYROID OPERATIONS

Access

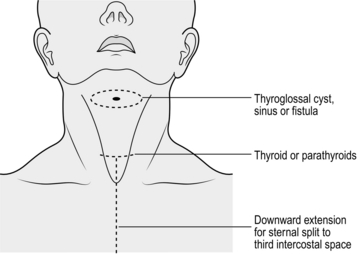

1. Check the position of the mark on the neck and adjust if needed. The incision gives adequate access to the upper pole vessels. It is typically two finger breadths above the clavicle, but be flexible, depending on the individual characteristics of the patient (Fig. 20.1). Place the incision between the sternomastoid muscles. Adjust the length depending on the size of the goitre.

2. Infiltrate the subcutaneous and subplatysmal layers along the intended incision with 20 to 30 ml of 1:200 000 adrenaline (epinephrine) in normal saline. You should prepare this in advance by mixing 0.5 ml of 1 in 1000 adrenaline (epinephrine) with 100 ml of normal saline. Allow time for it to have an effect prior to cutting.

3. Cut through skin, subcutaneous fat and platysma, taking care not to go deep to platysma where anterior jugular veins may be encountered. Use bipolar diathermy to control bleeding. Lift the platysma muscle of the superior flap upwards, dissecting to identify the subplatysmal plane. Develop the plane by sharp or blunt dissection or using diathermy or harmonic scalpel. By staying in this plane you will avoid damaging the anterior jugular veins and cutaneous nerves which lie superficial to the strap muscles.

4. Raise the upper flap as far as the thyroid cartilage and the lower flap as far down as the sternal notch. When this is completed insert a Joll’s or similar self-retaining retractor to the platysma and subdermal tissues at the midpoint of each flap and open it fully to expose the strap muscles. A second Joll’s retractor may be used for larger goitres.

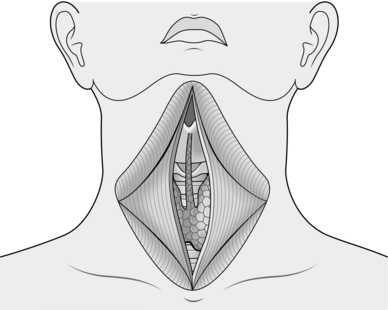

5. Identify the pale midline raphe between the strap muscles and incise it allowing access to deeper tissues. Now separate the strap muscles by incising along this line using diathermy or harmonic scalpel, until you see the thyroid gland (Fig. 20.2). At this stage have your assistant retract the strap muscles laterally and lift, while you apply pressure on the thyroid gland, pulling it towards you. Always handle the gland with care, using a gauze swab. Create a tissue plane between the strap muscles and the thyroid gland along its length.

6. Identify a ‘cobweb’ of fascial layers and divide them by a combination of blunt dissection and diathermy. As the last flimsy layer is divided, the vessels on the surface of the thyroid bulge as the restraining pressure is released from them. Dissection should be completely bloodless. Coagulate small vessels with bipolar diathermy, ligate and divide larger vessels with 3/0 vicryl ties. Divide the sternothyroid muscle (deeper strap) to improve access to the upper pole in larger goitres.

Action

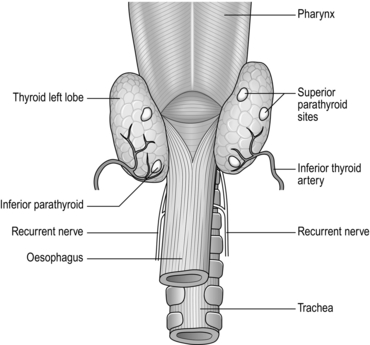

1. Stand on the side opposite to the lesion. Work across the surface of the gland, retracting it medially whilst your assistant retracts the strap muscles laterally and vertically on the strap muscles. Identify the middle thyroid veins if present and ligate them close to the gland, watching for the inferior parathyroid, which may be in close proximity.

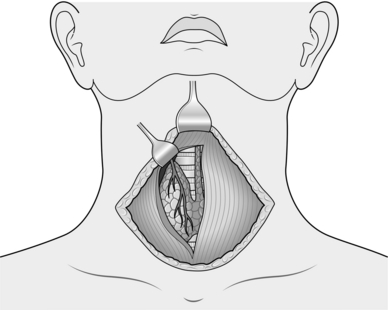

2. To allow the gland to be rotated medially and facilitate access to the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN) and parathyroid glands, the upper and lower poles must be freed and their vessels ligated. This can be achieved in any order. Working towards the upper pole place a small Langenbeck retractor superiorly and a large Langenbeck retractor laterally (Fig. 20.3). Gently push the upper pole of the thyroid laterally and create a tissue plane medially between the cricothyroid muscle and the superior thyroid vessels. Dissect in this plane using a fine haemostat. Coagulate small vessels with bipolar diathermy. By pulling the vessels laterally away from the cricothyroid you minimize the risk of damaging the external laryngeal nerve, as this can be difficult to identify. The external laryngeal nerve runs superiorly in close proximity to the upper pole vessels and usually lies either on, or deep to, the covering fascia of the cricothyroid muscle.

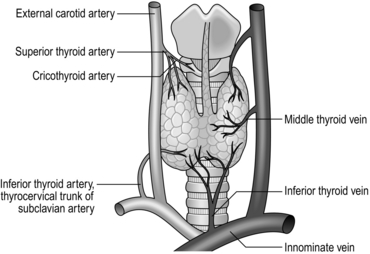

3. Gently dissect free the superior pole vascular pedicle both medially and laterally, using a combination of sharp and gauze pledget dissection. Place a Lahey or similar angled forceps, under direct vision, underneath the superior thyroid vessels. Once the vessels are isolated they can be clipped, divided and tied with 3/0 vicryl, placing two ties on the proximal stump. Clip and tie close to the gland avoiding damage to the external laryngeal nerve. Once the vessels are safely controlled, you can mobilize the gland inferiorly and medially. Look for branching vessels and the superior parathyroid gland, which often lies on the posterolateral portion of the gland. The vascular supply is displayed in Figure 20.4.

4. Move now to the lower pole and divide and ligate lower pole veins close to the gland. Once the upper and lower poles are controlled and dissected, the gland should rotate medially, allowing access to its posterolateral surface. At this stage you can change sides with your assistant and search for the RLN and parathyroid glands.

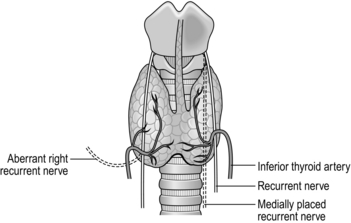

5. With a gauze swab on the gland, position your assistant to retract the gland medially. The strap muscles can be retracted laterally if needed. Dissect bluntly using a gauze pledget and identify the inferior thyroid artery and parathyroid glands. The RLN lies posteriorly and medially in the tracheo-oesophageal groove. Its position is variable anatomically and arises vertically on the left side, but more lateral to medial on the right. It can be found by careful dissection using non-toothed forceps and a mosquito artery clip. The RLN usually lies deep to the branches of the inferior thyroid artery, although it can lie in front of, or between, its branches (Fig. 20.5). In 17% of cases the recurrent laryngeal nerve is bifid for 1–2 cm before entering the cricothyroid muscle. The nerve appears white, usually with a small red vessel running on its surface. On the right side only, the nerve may be non-recurrent, coming directly either downwards or laterally across from the main vagal trunk. Once you have identified the nerve, trace it towards the cricothyroid joint, carefully dividing the tissue and small vessels that overlie it.

6. Now with the nerve in full view, look for the tongue-like, pinky-brown, upper parathyroid gland; it is usually adherent to the upper, posterolateral surface of the thyroid (Fig. 20.6). Dissect the parathyroid from the gland using bipolar diathermy preserved on its own blood supply. Once the parathyroids have been preserved, secure the branches of the inferior thyroid artery (Fig. 20.4) on the capsule of the thyroid.

7. The RLN enters the larynx at the cricothyroid joint. At its distal end it is covered by fibres of the lateral thyroid ligament (of Berry). Divide these fibres carefully using a small curved haemostat to create a tunnel parallel to the nerve. Do not apply a sling or retract the nerve. Once the nerve is freed and can be viewed along its entire length, divide the remainder of Berry’s ligament by sharp dissection. Dissect across the front of the trachea, separating the gland, using diathermy when necessary. Include the isthmus and dissect it out fully. Search for and dissect out a pyramidal lobe if present, up to the level of the hyoid bone.

8. The lobe to be removed, and the isthmus are now free. For a total thyroidectomy, repeat the procedure from the opposite side.

9. For a hemithyroidectomy, place artery forceps across the contralateral side of the isthmus, divide the gland and remove the specimen. Oversew the remnant capsule with a running Vicryl suture.

10. Check the anatomy, confirm the viability of the parathyroids. If one parathyroid gland is doubtful, remove it, mince it into small pieces and re-implant it, either in the sternomastoid or a strap muscle, marking its position with a non-absorbable suture. Assiduously seek and seal any bleeding points, checking the position of the nerve at all times. Ask your anaesthetist to perform a Valsalva manoeuvre (described by the 17th Bologna physician Antonio Valsalva) to highlight any occult venous bleeding.

11. Drains are not mandatory following thyroid surgery. They are rarely needed for lobectomies. If required, position a fine tube drain in the same skin crease as the skin incision to improve cosmesis. Secure the drain with a silk suture. Take care not to allow the drain to sit on the nerve as a neuropraxia may occur.

12. Normally remove the drain 12 to 24 hours following surgery.

Closure

1. Approximate the strap muscles with vicryl. Leave a small space inferiorly to allow blood to escape into the subplatysmal space in the event of bleeding. Close platysma and subcuticular layers with care with an absorbable suture such as 4/0 vicryl.

2. Use staples or subcuticular sutures for the skin closure. Remove staples by the third postoperative day. Remove non-absorbable subcuticular sutures after 1 week.

Postoperative care

1. Closely monitor the patient over the first few hours for respiratory distress that may indicate a haematoma. Haematoma in the thyroid bed can lead to upper airway obstruction as a result of laryngeal oedema. It is a surgical emergency requiring prompt exploration and evacuation in the operating theatre. Faced with a patient in extremis, be prepared to open the wound on the ward to relieve the pressure. Understanding wound closure is vital, as all layers need to be opened to relieve a haematoma in the thyroid bed.

2. In total thyroidectomy, check calcium on the night of surgery and the following morning. Check the patient for symptoms and signs of hypocalcaemia. Check that you have a protocol for calcium replacement if needed.

RETROSTERNAL MULTINODULAR GOITRE

Action

1. The mediastinum offers little resistance to an expanding goitre and the retrosternal extension can be significant. Most retrosternal extensions are into the anterior and superior mediastinum and can be safely delivered into the neck. Gentle traction along with blunt or finger dissection are often sufficient.

2. Occasionally they extend behind the trachea, enter into the posterior mediastinum and become intimately related to major vascular structures within the chest. Occasionally the blood supply is direct from the aortic arch – so-called thyroidea ima (Latin: ima: = lowest). Bleeding may be difficult to control and require a thoracotomy for access. Anticipate and identify the artery with care before ligating it. Attempt this procedure only if you are experienced.

3. You rarely need to divide the sternum to gain access to the superior mediastinum. If you cannot palpate the goitre in the neck it will be difficult to deliver. A largely intrathoracic goitre shaped like a tear-drop, with a narrow neck and wider, inferior bulk requires a sternal split to release it.

THYROGLOSSAL CYSTS

Appraise

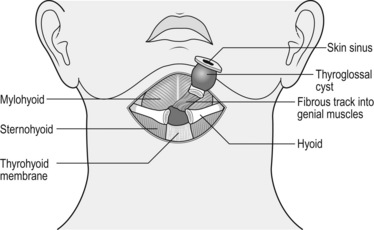

1. These cysts form from incomplete closure of the thyroglossal tract, which extends from the tongue base to the thyroid gland. They are situated between the thyroid and hyoid bone, to which they are intimately related. Although considered midline swellings, they are usually just off the midline to one side and usually present as painless lumps moving on swallowing or protruding the tongue.

2. Excise them both for cosmesis (Greek: cosmeein = to adorn; beautify) and because they occasionally become uncomfortable or infected.

3. Locate the cyst with an ultrasound scan and document the position of the thyroid gland prior to surgery. The mass could be an undescended gland rather than a cyst.

4. Thyroglossal cyst excision (Sistrunk’s procedure) was described by the American surgeon Walter Sistrunk in 1920. Any attempt to excise the cyst without removing part of the hyoid bone is likely to result in recurrence.

Action

1. Dissect out the cyst to define the tract in its upper position.

2. Separate the strap muscles and trace the tract up to the hyoid bone.

3. Strip the muscles off the middle portion of the hyoid bone using monopolar diathermy.

4. Excise the middle portion of the hyoid bone, since thyroglossal tracts have a complex relationship to the back of the body of the hyoid bone.

5. Transect the hyoid bone using small bone-cutting forceps just lateral to the cyst on each side (Fig. 20.7).

6. Follow the tract up into the neck, to the base of the tongue. Excise it as far up as possible. Surgery for recurrent thyroglossal cyst requires wide local excision of skin, subcutaneous tissue, strap muscles and hyoid bone. By performing the procedure in this way you minimize the risk of further recurrence.

REFERENCES

1. British Association of Endocrine and Thyroid Surgeons BAETS. Available at http://www/baets.org.uk. Accessed Nov 2010.

2. British Thyroid Association. Guidelines on the management of thyroid cancer. Available at http://www.british-thyroid-association.org/Guidelines/. Accessed Nov 2010.

3. Gleeson M.J., ed. Scott-Brown’s Otolaryngology, Head and Neck Surgery, 7th ed., London: Hodder Arnold, 2008.

4. Royal College of Pathologists. Guidance on the reporting of thyroid cytology specimens. Available at http://www.rcpath.org/resources/. Accessed Nov 2010.

5. The American Thyroid Association (ATA) Guidelines Taskforce on Thyroid Nodules and Differentiated Thyroid CancerCooper, D.S., Doherty, G.M., Haugen, B.R., et al. Revised American Thyroid Association management guidelines for patients with thyroid nodules and differentiated thyroid cancer. Thyroid. 2009; 19(11):1167–1214.

6. Watkinson, J.C., Gaze, M.N., Wilson, J.A. Stell and Maran’s Head and Neck Surgery, 4th ed. Oxford: Butterworth Heinemann; 2000.