Chapter 15. Thorax and Lungs

Rationale

Respiratory disorders are common in infancy and childhood and can be acute, life threatening, or chronic. Early screening and detection are essential to being able to refer children for medical treatment. Knowledgeable assessment also assists in monitoring the progress of treatment.

Anatomy and Physiology

Lungs have two main functions: to supply the body with oxygen and eliminate carbon dioxide and to maintain the body’s acid-base balance. The lungs are paired and symmetric. The right lung has three lobes, and the left lung has two lobes. Air enters the lungs via the trachea and larynx from the mouth or nose. The trachea branches into two major bronchi. The right bronchus is shorter, wider, and angled less sharply to the side than the left.

Fetal lung buds arise in the first lunar month of gestation, along with nasal pits, the trachea, and the larynx. Subsequent budding and branching create the mainstem bronchi pulmonary lobules in the second month. Branching continues into early childhood, although it is less proliferative. By the third month, elementary respiratory-like movements are observed. From the sixth month on, the lobules have developed alveolar ducts, and the ducts have developed alveoli.

As the alveolar sacs develop, the epithelium lining the sacs thins. Pulmonary capillaries press into the walls of the sacs as the lungs are prepared for the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide, near the end of the sixth month of gestation. During the final weeks of gestation the lungs secrete surfactants that reduce the surface tension of the alveolar sacs and prevent the alveoli from collapsing and producing atelectasis. At birth, the lungs are fluid filled. This fluid is rapidly dispelled and absorbed as the lungs fill with air.

The newborn infant’s thoracic cage is nearly round. Gradually the transverse diameter increases until the chest assumes the elliptic shape of the adult, at about 6 years of age. The infant’s thoracic cage is also relatively soft, which allows the cage to pull in during labored breathing. Infants have relatively less tissue and cartilage in the trachea and bronchi, which allows these structures to collapse more readily.

Airways tend to grow faster than the vertebral column. In infancy the bifurcation of the trachea is at the level of the third thoracic vertebra. By adulthood the bifurcation is at the level of the fourth thoracic vertebra. Smaller airways in young children and infants tend to narrow more readily from edema and secretions than in older children and adolescents. Shorter distances between structures in the young child also contribute to rapid transmission of organisms and widespread involvement.

Young infants (younger than 6 months) are obligatory nose breathers, and their nasal passages are narrower. Breathing is less rhythmic than in the child. In infants and children younger than 6 or 7 years, respirations are chiefly diaphragmatic or abdominal; in older children and especially females, respirations are chiefly thoracic. The volume of oxygen expired by the infant and the child is greater than that expired by the adult. The volume of air that is inspired increases as the child grows. At the age of 12 years the child has approximately nine times the number of alveoli that were present at birth.

As with heart rate, the respiratory rate in infants and children responds more dramatically than in adults to emotion, illness, and exercise. The rate tends to show greater variability and wider range than in adults.

Equipment for Assessment of Thorax and Lungs

▪ Stethoscope

▪ Pulse oximeter

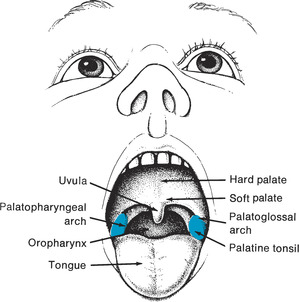

Ask the parent or child about cough (onset, progress, pattern, secretions), fever, shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, chest pain (or pain at the base of the neck), wheezing, easy fatigability, meningeal signs, abdominal pain, vomiting, sore throat, past respiratory tract infections, frequent colds, family history of respiratory disorders and smoking, history of allergies, immunization status, and type of child care setting (e.g., home, daycare) and environment (e.g., animals, birds, second-hand smoke).

Allow the young child to play with the stethoscope before you perform the assessment. Children often enjoy listening to the sounds in their chests and in their parents’ or the nurse’s chest. Remove the child’s shirt or blouse for best visualization of the chest. Infants and toddlers are often best assessed while held by their parents.

Assessment of Thorax and Lungs

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Assess for stridor (high-pitched crowing sound), grunting, hoarseness, snoring, labored breathing, audible wheezing, and cough (Table 15-1). | Clinical Alert |

| Stridor, hoarseness, and a barking cough accompany croup syndromes. Inspiratory stridor and expiratory snoring are indicative of epiglottitis. | |

| Precisely describe the sounds and their occurrence. | Audible wheezing can indicate asthma, respiratory syncytial virus, or foreign body aspiration. |

| Short, rapid coughs followed by a crowing sound or whoop indicate whooping cough. | |

| Snoring can indicate enlargement of the adenoids, polyps, or presence of a foreign body. | |

| A persistent dry cough that later becomes productive, hoarseness, and gasping and grunting respirations are found with congestive heart failure. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Observe the external nares for flaring. | Clinical Alert |

| Flaring is a significant sign of respiratory distress in infants (although this can also be observed in the crying infant). | |

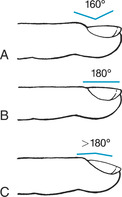

| Observe the nailbeds for color and for clubbing (widening and l engthening) of the terminal phalanges (Figure 15-1). | Clinical Alert |

| Cyanosis (bluish coloration of nailbeds) is sometimes indicative of respiratory failure. | |

| Cyanosis can also be related to vasoconstriction or polycythemia. | |

| Clubbing usually indicates chronic hypoxemia, as in cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis. | |

| Evaluate oxygen saturation (SaO2) levels through pulse oximetry. If using fingers for sensor placement, remove nail polish because it can distort readings. Placement distal to a blood pressure cuff can also distort readings. | The normal reference range for SaO2 for infants, children, and adolescents is 75% to 100%. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Mottling and cyanosis of the trunk indicate severe hypoxemia and usually are indicative of cardiopulmonary disease. | |

| Observe the color of the child’s trunk. | |

| Inspect the thorax for configuration, symmetry, and abnormalities. Measure the size of the chest by placing a tape around the chest at the nipple line. | The chest is rounder in young children. By 6 years of age the ratio of anteroposterior diameter to transverse diameter is about 1:35. |

| In some infants the sternum is so pliant that the chest appears to cave in with each breath. | |

| For greatest accuracy, record measurement during inspiration and expiration and average the two. Chest size is largely important in relation to head circumference in infants. | |

| The thorax should move symmetrically. | |

| Clinical Alert | |

| A round chest in an older child usually indicates a chronic lung disorder. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| A protuberant sternum (pectus carinatum, or pigeon breast) or depressed sternum (pectus excavatum) should be noted. Either can compromise lung expansion. | |

| Decreased movement of one side of the thorax can indicate pneumonia, pneumothorax, or a foreign body. | |

| Enlargement of one side of the thorax can indicate a diaphragmatic hernia. Enlargement of the left side can indicate an enlarged heart. | |

| Note the size of the breasts in relation to the age of the child. | Enlarged breasts can be seen in the young infant as a result of maternal hormonal influences. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Enlarged breasts (gynecomastia) in older male children can indicate obesity or hormonal or systemic problems. | |

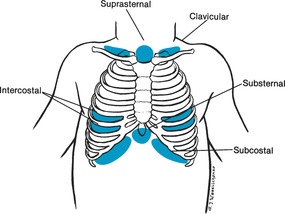

| Observe the chest for retractions, or indrawings, in the clavicular (above the clavicles), suprasternal (in the sternal notch), substernal (below the sternum), subcostal (anterior lower rib margins) and intercostal (between the ribs) areas (Figure 15-2). | Clinical Alert |

| Retractions indicate labored breathing in infants and children. | |

| Puffiness accompanies severe air trapping. | |

| Head bobbing in an exhausted or sleeping infant on inspiration can indicate use of accessory muscles and severe respiratory disease. | |

| Puffiness or bulging of these areas can also be present. | In children younger than 7 years respirations are diaphragmatic, and the abdomen rises with inspiration. In girls older than 7 years breathing becomes thoracic. Abdomen and chest should move together regardless of type of breathing. |

| Observe the child for type of breathing. |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Clinical Alert | |

| Abdominal breathing in an older child can indicate a respiratory disorder or fractured rib. | |

| In labored abdominal breathing the abdomen pushes out abruptly. | |

| Observe the depth and regularity of respirations and the duration of inspiration in relation to expiration. | Clinical Alert |

| A prolonged expiratory phase can indicate an obstructive respiratory problem, such as asthma. | |

| Deep respirations (hyperpnea) can indicate fever (the respiratory rate increases four breaths per minute for every degree increase in Fahrenheit temperature), respiratory acidosis associated with diabetes or diarrhea, or central nervous system involvements. | |

| Shallow respirations (hypopnea) can indicate respiratory acidosis that is associated with central nervous system depression or pleural irritation. | |

| Palpation | |

| To assess respiratory excursion, place your hands, thumbs together, along the costal margins of the child’s chest or back while the child is sitting. | Movement is symmetric with each breath. |

| Posterior base descends approximately 6 cm (2.3 in) during deep inspiration. | |

| Palpate for tactile fremitus by using either the fingertips or the palmar surfaces of your hands. Move symmetrically while the child says “99” or “blue moon.” | Fremitus is normally less at the base of the lung. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| Decreased fremitus can indicate asthma, pneumothorax, or a foreign body. | |

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| In the infant, fremitus can be felt as the infant cries. | Increased fremitus occurs with pneumonia and atelectasis. |

| Note other vibrations, as well, during palpation. | A pleural friction rub (felt as grating during respiratory movements) occurs with pneumonia and tuberculosis. |

| Crepitation (coarse, crackling sensation as fingers press against the skin) indicates escaped air from the lungs in the tissues, associated with injury or surgery. | |

| Percussion | |

| Percussion is more useful in older children. | Resonance (a low, long sound) is heard over all lung surfaces. |

| Using the indirect method, percuss the anterior and posterior chest. | Dullness can be heard over the fifth right intercostal space, because of the liver, and over the second to fifth left intercostal space, because of the heart. |

| Percuss over the intercostal spaces, moving symmetrically and systematically. | |

| The child can sit or lie while the anterior chest is percussed, and sit while the posterior chest is percussed. | Tympany (a loud, musical sound) can be heard over the sixth left intercostal space. |

| Clinical Alert | |

| The percussion note is dull if fluid or a mass is present in the lungs. | |

| Hyperresonance occurs during an asthmatic episode. | |

| Auscultation | |

| Using the warmed diaphragm and bell of the stethoscope, auscultate the lung fields systematically and symmetrically from apex to base. The bell is used for low-pitched sounds and the diaphragm for high-pitched sounds. | Breath sounds (Table 15-2) normally seem louder and harsher in the infant and young child because of the thinness of the chest wall. |

| Vocal sounds are normally heard as indistinct syllables. | |

| Assessment | Findings | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical Alert | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Report any adventitious sounds (Table 15-3) or breath sounds heard in other than expected areas. If unable to name the sound heard, describe it. | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Use a pediatric diaphragm or the bell for infants and small children. Children can be encouraged to breathe deeply by pretending to blow up balloons or blow out candles, or by blowing away a piece of tissue or cotton ball.

Auscultate the axillae of children with pneumonia.

Rales or crackles can be easily heard in these areas.

Auscultate for vocal resonance by asking the child to say “99” or count from 1.

Sounds can be referred from the upper respiratory tract if a child has mucus in the nose or throat. To determine if sounds are referred, place the diaphragm near the child’s mouth. Referred sounds are loudest near their origin and are symmetric.

|

Asymmetric rhonchi or wheezes can signal presence of a foreign body. Unilaterally absent breath sounds can indicate pneumothorax. In infants, breath sounds can be diminished, and not absent, in pneumothorax. Inaudible breath sounds and crackles can indicate severe spasm or obstruction during an asthmatic episode.

Decreased or absent vocal sounds are found with asthma, pneumothorax, or a foreign body.

Whispered pectoriloquy (words are heard on whispering), bronchophony (words are not distinguishable but sounds are clear and loud), and egophony (“ee” is heard as “ay”) can be indicative of lung consolidation.

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Altered tissue perfusion, cardiopulmonary: related to altered respiratory rate, use of accessory muscles, abnormal arterial blood gases, bronchospasm, dyspnea, nasal flaring, chest retraction.

Ineffective management of therapeutic regimen, families: related to complexity of therapeutic regimen.

Ineffective family coping, compromised: related to prolonged disease.

Altered parenting: related to illness.

Activity intolerance: related to imbalance between oxygen supply and demand.

Ineffective airway clearance: related to retained secretions, limited expansion of the chest wall, excessive mucus, presence of artificial airway, foreign body in airway, secretions in bronchi, exudates in alveoli, neuromuscular dysfunction, infection, asthma, allergic airways.

Ineffective breathing pattern: related to hyperventilation, pain, chest wall deformity, decreased energy, fatigue, neurologic immaturity, respiratory muscle fatigue.

Anxiety: related to change in health status.

Impaired gas exchange: related to alveolar-capillary membrane changes.

Risk for altered growth and development: related to infection, chronic illness.

Risk for altered development: related to chronic illness, technology dependence.

Risk for infection: related to exposure to pathogens, immunosuppression, inadequate acquired immunity, inadequate primary defenses, inadequate secondary defenses.

Sleep deprivation: related to stasis of secretions, fever.